What did ballet ever do to the world to deserve the way it’s always being represented by writers and filmmakers? Poor ballet! It’s so hard to get right; it’s so fragile an enterprise; it’s so battered by economic and sociological realities. Why does this fiendishly demanding but deeply rewarding process have to be distorted into an orgy of sadism, masochism, and misery? The latest avatar is the eight-part TV series Flesh and Bone, produced by the cable network Starz and starring the dancer Sarah Hay.

Yes, Nijinsky went mad, but he was a troubled young man—was it really Diaghilev and his Ballets Russes who pushed him over the edge? Yes, the great Olga Spessivtseva cracked up and was hospitalized for more than twenty years, but she seems always to have been unstable.

Meanwhile, the vast majority of the twentieth century’s leading dancers—from Pavlova and Karsavina through Markova, Danilova, Ulanova, Plisetskaya, Makarova, Fonteyn, Nureyev, Baryshnikov, Tallchief, and Farrell—led gratifying, untormented lives. They did not cut themselves, starve themselves (most dancers eat like crazy), commit incest, commit suicide, commit murder—they just applied themselves, day in, day out, to class, rehearsal, performance. “Tendu, tendu, tendu,” “plié, plié, plié,” then home to soak sore feet and sew ribbons on toe shoes. (Well, maybe a glamorous party or two—and in the case of Fonteyn, Diors and Balenciagas in the closet.)

One movie and one book paved the way for today’s ballet psychodramatics. The movie, of course, is Michael Powell’s incomparable The Red Shoes (1948), in which Vicky Page, played by Moira Shearer, cries out, “Why do I want to dance? Why do I want to live! Because I must!” And so she dies the death, torn between her love for her reliable composer husband and her obsession with ballet and the prodigious if sinister Boris Lermontov (a libel on the prodigious but hardly sinister Diaghilev). There have been other ballet movies, but nothing like this one in its opulence and ambitions. From a slow start, The Red Shoes became a tremendous box-office hit in both England and America (in New York, it ran at a small art house for more than two years); there’s no way of estimating how many little girls demanded ballet lessons in the wake of its gorgeous melodrama.

One of the most striking aspects of The Red Shoes is how over the decades it’s changed: not in its content, naturally, but in how we perceive it. In its early years, the 1950s, Vicky Page seemed to be the victim of the Svengali-like Lermontov, who manipulates her into abandoning her husband and domesticity in order to return—fatally—to his company to perform the Red Shoes ballet. In our more liberated day, it’s the husband who comes across as the bad guy: it’s his selfish requirements of Vicky that stand between her and her artistic destiny, and so drive her over the brink. Either way, though, she’s a victim—and victimhood is the heart of the quintessential ballet melodrama.

The literary version of all this is Gelsey Kirkland’s notorious memoir of 1986, Dancing on My Grave. She’s the victim of everyone and everything, starting with her perfectionist father (the author of the play Tobacco Road) and featuring the tyrannical George Balanchine, whose crime lay in rigorously training her and starring her at his New York City Ballet. And then there’s her drug addiction, her self-loathing (horrible efforts to alter her looks), her eating disorders, the casual behavior of her most famous dancing and sexual partner (Baryshnikov), the drug death of her later dancing and sexual partner, Patrick Bissell, and most of all, her seething anger.

But why blame Daddy, Mr. B, Misha, or Lermontov, when you can blame the real villain: ballet itself? If Vicky, Gelsey, and other martyred heroines had never been bitten by the ballet bug, they could have led normal, wholesome lives.

Times have changed, however, and although terrible things continue to plague fictionalized ballet heroines, something different and up-to-date is also taking place: Claire Robbins, the heroine of Flesh and Bone, finally refuses to succumb to abuse. Being a modern liberated young woman, she learns to take charge of her life, to be her own woman, to say no to her oppressors, from her toxic family to her toxic artistic director, a two-bit Lermontov. In fact, the last word spoken in Flesh and Bone is her defiant “No!” Her significant progress hasn’t been from corps girl to prima ballerina but from victimhood to assertion. Just in time, she’s discovered her self-worth!

When we first encounter Claire, though, ballet is an escape route, not a transcendence. She’s climbing out of the window of the grim house in Pittsburgh in which she’s living with her father and brother—presumably they would forcibly prevent her from leaving in a more orthodox way. Well, maybe they would: Daddy is a beer-chugging invalid, raging at the universe; brother is a violent ex-Marine whose relationship with Sis has been, to put it tactfully, seriously unconventional. A few years ago, Claire was an up-and-coming apprentice in a local ballet company, but she dropped out—because, as we eventually learn, she’s been inconveniently made pregnant by Bro.

Advertisement

No matter. Claire hops a bus for New York, proceeds at once to an open audition at the “American Ballet Company,” and though she apparently hasn’t taken class for years, is exhausted by her bus trip, and has no particular glamour, she is immediately hired by ABC’s volatile artistic director, who decides practically on the spot that she’s the Future and dumps plans to open his new season with Giselle in favor of a cutting-edge new piece that’s to be tailor-made for her.

This doesn’t go down well with all the other girls, who are relentlessly bitchy, and it really gets under the skin of the company’s leading ballerina—in fact, its only ballerina, so far as we can see. The very glamorous Kiira (effectively played by the ex-ABT dancer Irina Dvorovenko) is approaching the end of her glorious career but—and this is the most realistic thing in the series—she’s in denial: she’s convinced that she can go on…and on. Fortunately for Kiira, when she finally has to acknowledge that the bell has tolled for her at last, she has an adoring rich husband, an assortment of past and present lovers, and her cocaine habit to cushion the fall.

There seem to be fewer than thirty dancers at the American Ballet Company, which is nevertheless presented as a major organization. The only visible principals are Kiira (until she’s gone) and a single male (another ABT refugee, the estimable Sascha Radetsky). There’s a talented black guy in the corps who’s amusingly campy, though ruthlessly ambitious, but the rest of the corps are mostly undifferentiated.

Only two of the girls stand out: red-headed, promiscuous, deeply insecure Mia, Claire’s roommate, who it turns out (are you ready?) is going blind; and self-assured rich girl Daphne, who buys a promotion to soloist but whose main function is to introduce Claire to the fancy strip joint where Daph enjoys performing with a pole when she’s not back in the studio practicing her fouettés. Club Anastasia is run by a charming but vicious Russian thug who happens to be in love with ballet. His favorite is Swan Lake, and he arranges to have Claire, whom he instantly recognizes as a special soul, too fine for poles, to dance the famous second-act solo before a throng of rich people on his large yacht out in New York harbor. Oh—I almost forgot: there’s a mini-subplot about the Russian mafia that comes out of nowhere and disappears without a trace.

Claire, we’re constantly reminded, is a tremendous talent, a judgment confirmed by the cutting-edge choreographer Toni Cannava, a tall rakish blonde who is hired to create the masterpiece that will pull the American Ballet Company out of its artistic doldrums. Yet Claire is somehow emotionally blocked. (She also has some bad habits, like self-mutilation.) She has to learn to expose her feelings. “Show the camera your marrow,” dictates artistic director Paul Grayson. “Strip yourself bare. Let it devour you.” She does her best, but even after Paul flicks his member at her to make his point, men (always excepting Brother Bryan) just don’t get through to her.

Throughout the series we get to watch ABC rehearsing, and eventually performing, Balanchine’s Rubies (a touch of class), but the focus is on the new ballet Toni Cannava is creating. It’s called Dakini, a Tibetan Buddhist manifestation of some kind of spiritual progress (if I understand its Wikipedia entry), and somehow it mirrors Claire’s progress from victimhood to womanhood. The actual choreography is by the superb ex-dancer Ethan Stiefel, but I’m afraid it’s the usual crummy business of lifts, lifts, lifts: up Claire goes, down Claire comes. It’s about as cutting-edge as celery, and next to Rubies looks pathetically reductive.

It would be easy, and fun, to go through Flesh and Bone and laugh at all the blunders and misrepresentations, but I’ll let one stand for all. Suddenly, in a fit a pique—his natural state—artistic director Grayson turns on one of the corps girls, shrieking the equivalent of “You’re fired! Get out of here!” and the poor girl slinks off, never to reappear. Grayson has presumably internalized Donald Trump’s management techniques from The Apprentice, but apparently neither he nor anyone else connected to Flesh and Bone has ever heard of contracts and unions.

Advertisement

Sarah Hay, a pleasing if not exceptional American dancer, was “discovered” to play Claire, and at the start there was a fuss about her cleavage, considered by some as excessive for a ballerina. But she stuck to her guns, and I’m certainly not complaining. Hay is perfectly adequate as both a dancer and an actress—it’s not her fault that she’s hardly the incomparable performer she’s meant to be.

She even works convincingly with the series’ remaining major (and most irritating) character, Romeo, a homeless literary schizophrenic, played by Damon Herriman, who hangs out at the brownstone where Claire and Mia live, benignly watching over them. Claire responds to his kindness, little knowing that at the very moment of her overwhelming triumph in Dakini, while the audience is standingly ovating, Romeo is stabbing Brother Bryan to death in Central Park. You may ask yourself why he’s wearing a coat he’s patiently fashioned for himself out of bottle caps. Just don’t ask me.

All this plot—plus a lot of gratuitous sex (Bryan humping Mia, but only after tying her up; Paul humping his cute ethnic rentboy)—emphasizes the fact that Flesh and Bone is pure soap opera, masquerading as, or aspiring to be, an illuminating look at the world of ballet. The obvious comparison is to the award-winning movie Black Swan (2010), a confused psychodrama about deeply disturbed characters in a semi-surreal world. In a word, Flesh and Bone is merely ridiculous; Black Swan is inflated, arty pretention. Neither has much to do with the way ballet really works, but given the choice, I’d go the soap opera route any day. Besides, it’s fun watching Dvorovenko go to town in Rubies. In soap opera as in real life, Balanchine comes off best.

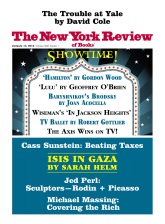

This Issue

January 14, 2016

ISIS in Gaza

How to Cover the One Percent

A Ghost Story