What kinds of narratives fit comfortably into the short-story form? An impossible question: at no time has there been any general consensus about how to answer it, and anyone who tries to formulate such an answer usually becomes the victim of critical potshots. But the issue is worth raising, because even a partial explanation might tell us what short stories actually do, what part they play in our culture, and why writers go on stubbornly committing them to print.

Sonnets are better at describing matters of the heart than at depicting, say, the Battle of Austerlitz. Short stories, given their form, are probably better at dramatizing certain subjects rather than others. But which ones? Probably the most notorious response to this question has been Frank O’Connor’s The Lonely Voice: A Study of the Short Story, which started as a series of lectures at Stanford and was first published in 1963. Its arguments are exciting, mind-haunting, and occasionally, thanks to its wild claims, “far from wise,” as Russell Banks writes in his otherwise laudatory introduction to the 1985 reissue.

O’Connor’s central idea is that the short story is a more private art than that of the novel. And its dramatis personae are of a different order: more solitary, isolated, and uncommunicative. Going out on one of several limbs, O’Connor claims that we do not identify with most short-story characters. Instead, we find in stories “a submerged population group” made up of lonely outcasts, “outlawed figures wandering about the fringes of society, superimposed sometimes on symbolic figures whom they caricature and echo….” He is thinking here of Gogol’s “The Overcoat” and its central character, Akaky Akakievich, and Akaky’s distant, echoing similarity to Christ:

What Gogol has done so boldly and brilliantly is to take the mock-heroic character, the absurd little copying clerk, and impose his image over that of the crucified Jesus, so that even while we laugh we are filled with horror at the resemblance.

Allied to romance rather than realism, the short-story form, O’Connor suggests, does not provide the kind of necessary space for a writer to build up a worthy and heroic individual as novels do. Remembering an author’s stories, we therefore recall a population group and not an individual. As a consequence, what we encounter in short stories are these exemplars of various subcultures, “remote from the community—romantic, individualistic, and intransigent,” a class of people who were largely invisible to us before our reading. Accordingly, the central feeling of short stories, O’Connor asserts, is that of the loneliness associated with that particular group.

O’Connor’s list of these submerged population groups includes “Gogol’s officials, Turgenev’s serfs, Maupassant’s prostitutes, Chekhov’s doctors and teachers, Sherwood Anderson’s provincials,” to which, in the spirit of things, one might add Poe’s madmen, Cheever’s suburban commuters, Welty’s genteel southerners, Alice Munro’s small-town Canadians, Salinger’s adolescents and children, Edward P. Jones’s African-American inhabitants of Washington, D.C., Grace Paley’s New Yorkers, Denis Johnson’s addicts, Louise Erdrich’s Native Americans, and Raymond Carver’s hardscrabble part-timers. More recently, George Saunders’s haplessly eager victims of hallucinatory capitalism seem to have walked straight out of O’Connor’s theory.

O’Connor’s book has had a certain staying power despite all the holes in its arguments and the numerous exceptions one can think of. His formulation is site-specific: as he acknowledges, the theory applies to North American and Irish writers in a way it does not for those from other cultures. And it doesn’t really account for the rise of the shadowy antihero in the nineteenth- and twentieth-century novel. Something is off, or some element is missing entirely.

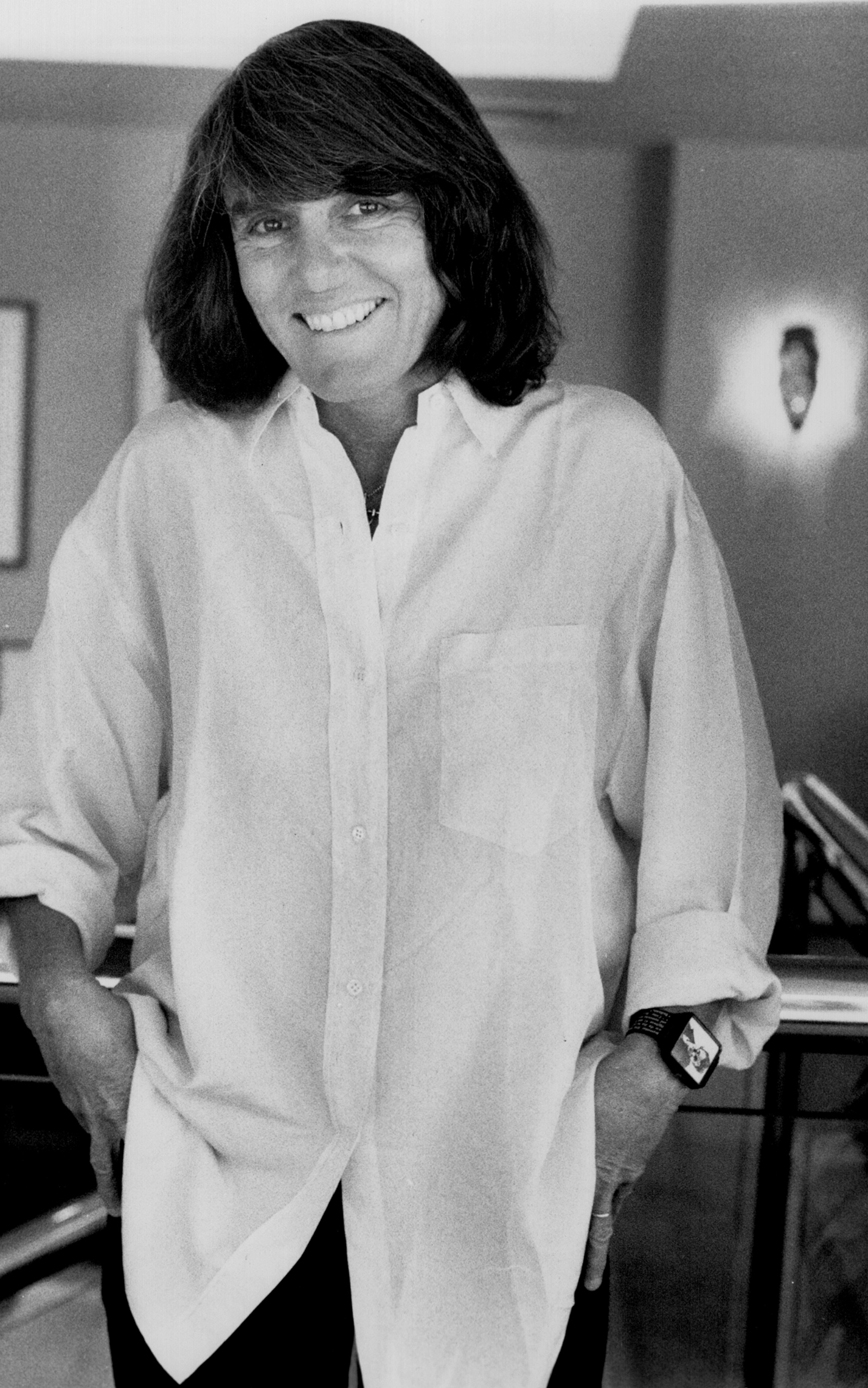

Advancing through Joy Williams’s The Visiting Privilege: New and Collected Stories, the reader is likely to notice a pattern in the narratives that’s so prominent and obvious that it might prompt another claim about what short stories characteristically do—a kind of supplement to O’Connor’s. Given a twist, so that the theory depends on behavior rather than identity, one might say that short stories—and Joy Williams’s are exemplary in this regard—thrive on impulsive action that comes out of nowhere, that is unpremeditated, unplanned, and unconsidered and is therefore inexplicable. Her characters seem to be in the grip of a god or a demon and seem to be following orders whose logic even they could not possibly justify.

If short stories constitute the Theater of Impulsive Behavior, there must be a reason: the limitations of the form tend to reduce the amount of history that can be shoehorned into the narrative. As anyone who has tried to write a story knows all too well, you can’t load on massive quantities of background information at the beginning of a tale without making readers feel uneasily that they have come into the movie late. Novels are quite comfortable about establishing lengthy histories, but short stories are not; they don’t have the time for it. In this particular genre, the God of Impatience rules.

Advertisement

But if you cut out much of a character’s history, you also cut out much of his motivation for action. You can no longer show a character’s lengthy deliberations prior to making a fateful decision. That’s the territory of the novel. Instead, with the contraction of narrative time, and with the character’s past chopped off and a possible future truncated or missing altogether, the protagonist simply acts, going from here to there without entirely grasping why she did what she did and often having no idea of how she ended up where she is now. She experiences the tyranny of the present presiding over an obliterated past.

Furthermore, when the character arrives in the nowhere to which her trajectory has led her, she’s not inclined to settle down. Why should she? She must either keep moving or patch a life together somehow, and if she tries domesticity, her reliance on the glue of love, which is as unconsidered and impulsive as all the other emotions, will prove to be weak and susceptible to breakage.

Like it or not, this vision of a population blown around by its own impulses has struck many readers as an accurate depiction of the way a sizable number of Americans typically behave. The pure products of America are going crazy on a regular basis these days. Unmethodical and uprooted erratic behavior is our signature, our keynote. If a character is incapable of planning anything or remembering her own history, then where does she belong? In with a shadowy, helter-skelter submerged population group, that’s where.

The Visiting Privilege, titled inaccurately as a volume of Joy Williams’s collected stories, omits several from her previous books, including “Woods,” “Building,” and “Traveling to Pridesup” from Taking Care (1982), “The Route” and “Gurdjieff in the Sunshine State” from Escapes (1990), and “Claro” from Honored Guest (2004). Those that do appear have been revised and in most cases streamlined, making the velocity of the action even faster than it was before. And the style, which to my ear begins with overtones from Donald Barthelme deployed for domestic semirealism, is notable for its progression of breathless and vehement declarative sentences, usually unmarked by commas:

I am so weary I can hardly lift up my hand to my head. I must make dinner for us but I think the simplest omelet is beyond my capabilities now. I suggest that we go out but he says that he has already eaten with the tutor. They had tacos made and sold from a truck painted with flowers and sat at a picnic table chained to a linden tree. I have no idea what he’s talking about. My rage at Jeanette is almost blinding and I gaze at him without seeing as he orders and reorders his papers, some of which seem to be marked with only a single line. I feel staggeringly innocent.

Note the absence of qualifiers, the exhaustion, the rage, the disingenuousness, the inability to sit down. Joy Williams’s stories contain many different situations, of course, and their prose glitters with acute perceptions on the part of the characters (“Life was like a mirror that didn’t know what it was reflecting”), but their perceptions and insights rarely do anyone much good. The narrative rhythms have the energy and tone of screwball comedies that somehow have taken an unexpected left turn toward tragedy without quite arriving there, but with the tragedy always in view, off in the distance, unavoidable.

Using this method and this tone, Joy Williams has written several great stories, among the best we have in contemporary letters, located in a book that is almost impossible to read straight through. There is such relentless vehemence in the exposition and drama that reading too many of her stories at one sitting can turn into an ordeal. The terrible suffering, viewed at sixty miles an hour in a landscape infused with unappeasable longings, inspires a kind of awed fascination. Imagine a marathon of Preston Sturges movies going on for days, their hypermanic characters gradually wearing down the viewer into submission, with all the comedy growing bleaker by the minute, and you have a sense of the reading experience of The Visiting Privilege. The only way to read it properly is by slow increments, one story at a time, with pauses for recovery.

Joy Williams’s first collection contained one of her least characteristic stories (though one of her finest), “Taking Care.” The story showed a direction that, for the most part, her stories did not subsequently take. Its protagonist is Jones, a preacher, whose downfall has been his capacity for love. “As far as he can see, it has never helped anyone, even when they have acknowledged it, which is not often. Jones’s love is much too apparent and arouses neglect.” In the world of these stories, Jones’s generosity of spirit makes him a victim, particularly of his daughter’s flighty psychopathology. She has had a baby and soon after its birth has given over its care to her parents while she spends her time wandering through Mexico.

Advertisement

Having done so, Jones’s daughter anticipates having a breakdown. She “has seen it in the stars and is going out to meet it” and in the elongated eternity of her present life ambles through Mexican jewelry shops looking at Fabergé-like eggs. Fate, meanwhile, has given a blood disease to Jones’s wife. She has spiritually abandoned Jones, the story tells us; “she is a swimmer waiting to get on with the drowning.” The pathos intensifies: taking care of his wife, the baby, and a dog, Jones puts on a phonograph record for consolation, whereupon fate intervenes again. The record is, of all things, Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder, and Kathleen Ferrier is singing them. In the early version of the story, Jones knows some German and plays the record “again and again,” but in the revised story in the collection under review he listens to it only once, but closely enough to register these lines: Oft denk’ ich, sie sind nur ausgegangen,/Bald werden sie wieder nach Hause gelangen (“I often think: they have just gone out/And now they will be coming back”). It is as if circumstances have gleefully conspired to intensify his sorrow.

At the story’s end, Jones is picking up his wife, “thin and beautiful,” at the hospital. He has cleaned up their house in preparation for her return to it, and in the story’s last sentence, one tinged with muted radiance, “Together they enter the shining rooms.” Her arrival at home, into the shining rooms, constitutes the only heaven that the story affords. What’s notable about the stories that follow is how infrequently characters like Jones—people with settled, steady attachments and a feeling for the care of others—appear in them. Instead, the norm involves children or young adults with often-divorced parents (“Fortune”), or the children of murderers (“The Blue Men”) or their parents (“Brass,” “The Mother Cell”), or alcoholics (“Escapes,” “White,” and many others), those who have attempted suicide, and the innumerable characters who are afflicted with obsessions that seem almost god-struck in their intensity. Jones has been left behind, but we will see variations on his daughter many times again.

The one other story in which Jones appears, “Bromeliads,” presents us again with his predicament. “He senses that he has fallen into this room, into, even, his life.” Then he realizes that what he has been thrown into is the present—but a particularly empty present, one that seems to have little or no relation to its own history. “He is in the present, perfectly reconciled to the future but cut off from the past.”

Of course these kinds of tales can be imported into the novel form, but I find Joy Williams’s novels, for all their brilliance, often too frantic for my taste, and, in an odd way, too brightly lit, or as if, to change metaphors, they had been written in too high a key. The Quick and the Dead (2000), for instance, has a marvelous central character, a young woman named Alice, beset with inner rage and dedicated to ecoterrorism. But the book in which she appears is crowded with so many marvels and weirdos and characters vying for the reader’s attention that the effect is a bit like an opera that consists entirely of arias, with almost no transitions, with the apparent presumption that our attention is bound to flag and fail if the style drops from its customary high coloratura volume and nonstop eloquence. There is never a dull moment, and very little modulation, and that is the trouble.

Her essays, in Ill Nature (2001), subtitled “Rants and Reflections on Humanity and Other Animals,” have some similar qualities, though in this case with clear targets: overpopulation, hunters, safaris, environmental degradation, cruelty to animals. As advertised, the essays often have the quality of rants, but in almost every case the rage they contain seems like a perfectly appropriate response to the monstrous practices they depict. There is an art of the rant, and Joy Williams possesses it. The book concludes with a kind of ars poetica: any author “writes to serve…something.” Later she identifies this “something” with “that great cold elemental grace that knows us.”

Well, maybe. This particular formulation sounds religious, but the face we view in The Visiting Privilege often looks out with the mad, blank stare of Jared Lee Loughner, the mass-murderer of six people at a Tucson shopping mall in 2011, and who is the real-life protagonist of one of the new stories, “Brass.” D.H. Lawrence’s verdict in Studies in Classic American Literature that “the essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer” comes close to getting at the fixed-but-empty concentration of so many of the characters in these tales. They seem so eager to shed their pasts that their behavior seems to be unmapped on any psychological grid. Nor have they signed any social contract.

Nevertheless, characters like Jared Lee Loughner have become so common these days that we now take them for granted. As Jared’s father, the narrator of “Brass,” says, “No, we were never afraid of him. Afraid of Jared?”

The American settings, too, have acquired here the hard glossy patina of madness. “She was living in a motel out on the highway that was next to a burned-out gas station and a knife outlet.” Sometimes the settings themselves seem to be sentient:

But how could he hear her? This annoying room was listening to every word she uttered. And what did it know? It couldn’t know anything. It couldn’t climb from the basement into a life of spiritual sunshine like she was capable of doing, not that she could claim she had. The individual in the hall howled with laughter at this. There were several of them out there now, a whole gang, the ones from the dinner party, probably, the spectacular-wrecks people, just shrieking.

Other characters in these stories are under such heavy psychic pressure much of the time that we wait for them to explode, which they do with some regularity, usually in the form of a monologue that starts up and cannot stop itself. Williams is a specialist in the out-of-control speech that gradually loses its bearings and wanders comically and eloquently in a mad dash from one vanishing thought to another. “Cats and Dogs,” “Hammer,” “The Other Week,” and “Rot” all contain crazed moments of brilliant speechifying that in their unsettled brilliance can rival similar moments in the work of Don DeLillo and Philip Roth.

Accordingly, given the absence of steady thinking and the characters’ inability to concentrate, many of the stories take the form of subverted quests. If a character sets out at the beginning of a story to go to a funeral or to visit a friend, you can be sure that she or he will arrive somewhere else, a place out in the middle of nowhere, like the Motel Lark and its horrific environs. “She squinted, frightened, at black heaps along the shoulder and in the littered grass, but it was tires, rags, tires. Cars sped by them. Along the median strip, dead trees were planted at fifty-foot intervals.”

Joy Williams has also mastered all the elements of distracted attention, including non sequitur dialogue in which the participants are only half-listening to each other, and questions that have so little hope of being answered that they lack an upward inflection and a question mark. These moments are decorated with what James Agee once called “expressive little air-pockets of dead silence.”

“You’d like Donna,” Bliss said to Joan. “You know where she’s from? Panama City.”

“How’re she and Harry doing,” Daniel asked.

“Time has wrought its meanness on their attachment,” Bliss said. “You know what I told her? I told her, to God both the day and the night are alike, so are the first and last of our days.”

“My, that’s very good,” Daniel said, “but a bit cold.”

These stories, with their characters weighed down with inarticulate eloquence, strike a very clear note. What they generally lack in pathos, they make up for in dark comic energy. Witty, and with a concert-hall pitch for American idioms, the stories glitter with a bright, desolate light. The characters, many of them, seem to have just awakened from shock treatment and are groping to remember anything at all. In a sentence that seems to have caused Joy Williams a lot of trouble, the story “Marabou” concludes, in its first version in Honored Guest, this way:

It would never be that once, again, when she’d learned that Harry died, no matter how much she knew in her heart that the present was but a past in that future to which it belonged, that the past, after all, couldn’t be everything.

In its new version in the volume under review, the sentence has been revised, and its meaning has changed:

It would never be that once, again, when she’d learned that Harry died, no matter how much she knew in her heart that the past was but the present in that future to which it belonged.

In the second version, if I am reading it correctly, the past is not only incapable of being everything, it has vanished altogether. Welcome to crazy times.

This Issue

January 14, 2016

ISIS in Gaza

How to Cover the One Percent

A Ghost Story