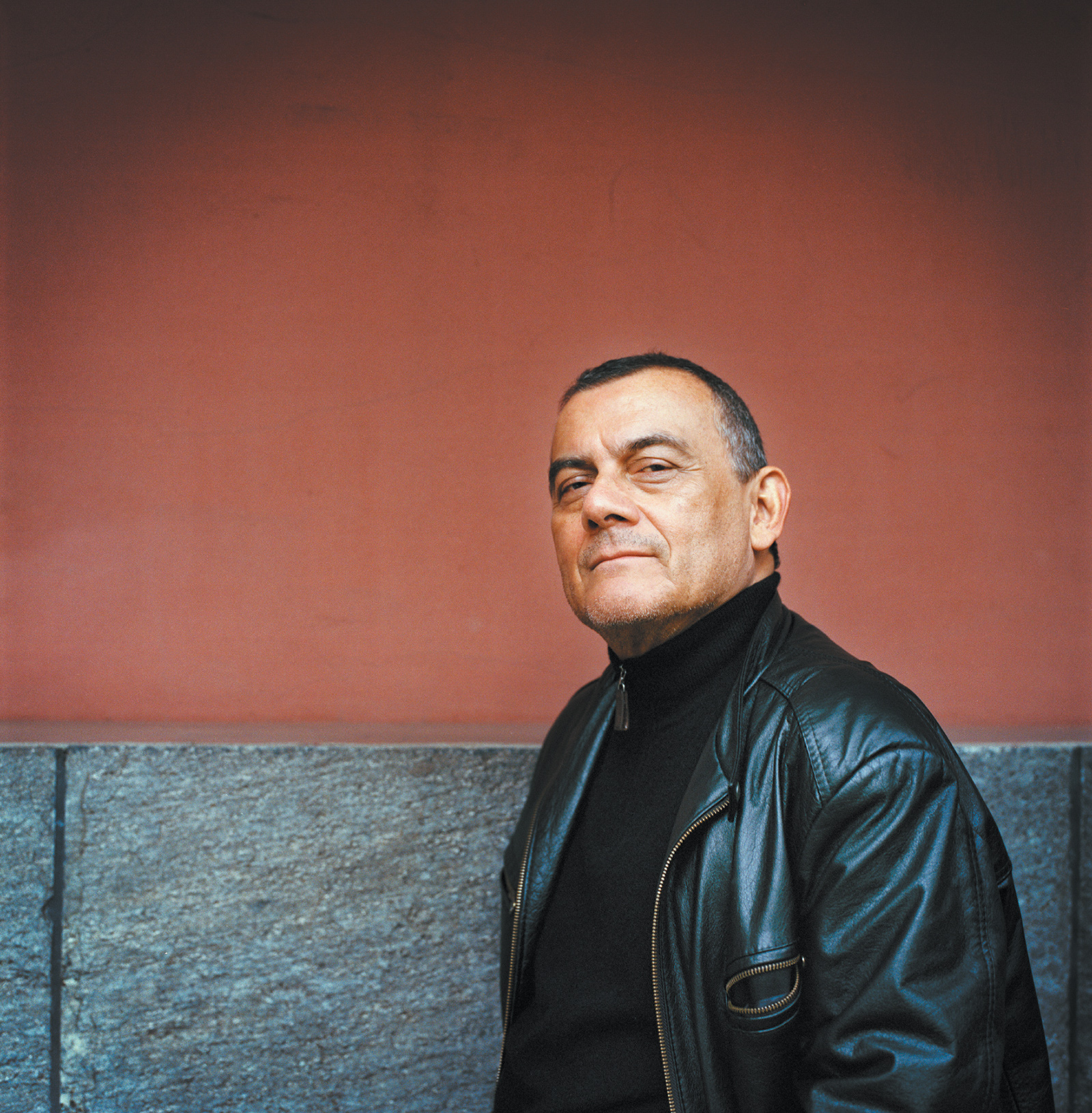

How to place the savage fictions of Horacio Castellanos Moya? Now fifty-seven, Castellanos Moya is a stellar fixture in the still-running second boom in Latin American literature, whose leading artist is the late Roberto Bolaño. The booms (the first, in the Sixties and Seventies, and the second, late Eighties and ongoing) are porous constructs with writers like Mario Vargas Llosa and Luisa Valenzuela starring in both of them. Compared to the works of Gabriel García Márquez, Carlos Fuentes, and Julio Cortázar, to mention just the best-known names, the works of the second boom are bleaker, a little less operatic, and differ more among themselves—but perhaps the most different among them are those of Horacio Castellanos Moya.

A main thing that sets Castellanos Moya apart is his intense concentration on his home country of El Salvador and the US-sponsored counterinsurgency wars and terror afflicting that region in the 1970s.* His eleven novels and five collections of short stories descend directly or indirectly from the enormities of this time and place. He goes over the same ground from different angles, reuses characters at varying stages of their fates, follows entire families, all with an eye to the damage done to these—mostly—peripheral players in the tragedy of El Salvador. Moya’s instinct for the jocular also demarcates his work: he captures the noir absurdities that arise in the most mordant or unlikely settings. His latest novel, The Dream of My Return, presents in compact and indelible form his tricks, his daring, his disgust, his humor.

Erasmo Aragon, a Salvadoran exile in his forties, the narrator of The Dream of My Return, has been working as a journalist in Mexico City for the last five years. He is married and has a young daughter. It’s 1992 and the civil war in El Salvador is ending. A peace treaty is imminent. He has a month to complete the preparations for his return. He ought to be happy. However, he is suffering from obscure pains in his liver, and his regular doctor, a homeopath, has abruptly and permanently returned to Spain.

Erasmo finds another doctor, one Don Chente, an odd duck. This doctor first treats his pain with acupuncture, but decides that a cure will require therapy by hypnosis. He proposes various contradictory etiologies for Erasmo’s distress. One of them is this:

When humans took shelter in caves and were forced to live a sedentary life, they discovered that they did not like to defecate or urinate where they slept…. This was also the first time a human being experienced the emotion we now call anxiety, which consists of having to choose between two options: either he satisfies his instinct to empty himself wherever he happens to be, which means he’d have excrement next to his bed,…or…elsewhere…. Anxiety and bowel control are closely related…. This is the cause of Irritable Bowel Syndrome…. This is your ailment.

Although he is quite taken by this theory, Erasmo reminds Don Chente that it is his liver and not his colon that is hurting. Don Chente immediately produces a different diagnosis, one that will require hypnotherapy focusing on Erasmo’s maternal grandmother:

She had devoted her life to crushing my image of my father with the greatest possible cruelty, and it was precisely this damage to my father figure that was undoubtedly the main cause of my ailments.

Erasmo goes for it. He comes from an old conservative Salvadoran family associated with the formerly powerful National Party. He has vague memories of traumas in his boyhood, including his father’s assassination by an unknown killer and seeing the front of his grandmother’s home blown up. Radicalized, he worked briefly for a rebel periodical before going into exile. He is pretty much an homme moyen of his social class. His mental furniture is ordinary, much of it consisting of items from American popular culture. He is no longer concerned with political ideas in any substantive way. His own concerns and ailments interest him, but he has no strong feelings for his wife and daughter, who are to be left behind when he returns to El Salvador.

The hypnotherapy sessions commence. Erasmo is counting on the success of this process to heal his liver pains. The memories he is supplying as raw material to enable Don Chente to create in him a new self-understanding seem increasingly specious to Erasmo. While in a trance state, he free-associates about his life. He awakens from these trances with no memory of what he has said. He never sees the record of his sessions that is kept by Don Chente in a notebook that ultimately disappears—as, for a while, does Don Chente.

Erasmo’s marriage is further weakened by sudden reciprocal confessions of cheating. Oddly, he is annoyed enough about it to arrange for an exile friend of his—a hit man and gun runner for the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front—to kill Antolin, his wife Eva’s lover. The hit man, whose nom de guerre is Mr. Rabbit, is to tail Antolin in order to get his address. Erasmo waits in the car while Mr. Rabbit is ascertaining Antolin’s apartment number, and is horrified when Mr. Rabbit returns and tells him that he has found Antolin at home and expeditiously killed him. Erasmo concludes that he must himself have been bluffing when he commissioned this hit. In any case, Mr. Rabbit placates him by utterly changing his story: he has only shot up a flower pot outside Antolin’s door, as a warning. Mr. Rabbit presents his pistol, still warm and smelling of gunpowder. The actual truth of what has taken place is never revealed.

Advertisement

Erasmo is desperate for his liver pains to subside (although not desperate enough, one notices, to curtail his episodic blackout drinking binges). As the hypnotic sessions continue, he experiences deepening mistrust in the accuracy of the memories that he believes he’s supplying to Don Chente—at least the ones he’s thinking about as he goes into the therapeutic trance. And he is realizing that not only are these memories suspect but the only ways he can think of to verify or refute them are chimerical:

I had been certain that my first childhood memory,…the point at which I would have to begin to tell the story of my life, was of the bomb that destroyed the façade of my maternal grandparents’ house…, and my memory consists of one precise image: my grandmother Lena carrying me in her arms across the dark courtyard…. That was the image I returned to with a certain amount of pride whenever I was called upon to explain how violence had taken root in me at the very beginning of my life…. The truth is, I suddenly found myself wondering,…how this almost cinematic image had lodged itself in my memory, considering the fact that if I was in my grandmother Lena’s arms, it wouldn’t have been possible for me to have seen myself from the outside…. I was doubting the veracity of my first memory.

The only way to confirm what my memory was telling me was to travel to Honduras to ask my grandmother Lena,…but I soon thought better of it, it would be utterly senseless to go visit my grandmother Lena, who, at eighty years old, was suffering small strokes that would soon leave her in a state of limbo, and perhaps my memory had been shaped precisely by what she had repeated to me over and over again, whenever her buttons got pressed and she’d begin to rant against the Liberals, whom she never distinguished from the Communists, blaming all of them for whatever was wrong with her country; moreover, I had absolutely no interest in traveling to Honduras….

Erasmo’s problems with his own power of recall are not helped by a critical feature of the Mexico City exile milieu he inhabits: his associates chronically dissemble, revise past roles, plead amnesia. People seem to recall his doctor Don Chente as both a suspected Communist and a CIA agent. At a social gathering, Erasmo’s uncle Munecon faces accusations of involvement in a nasty collaboration between Communists and right-wing death squads. Munecon denies it and begins to tell the story of the murder of his own son by death squads, but Erasmo derails and distracts him: the story is too long for Erasmo, and he has heard it too many times.

We take leave of Erasmo as he approaches the departure gate at the Mexico City airport. There is a bathetic conclusion in keeping with the fantasia of misconception leading up to this moment:

I would board the airplane that would carry me to a new phase in my life, to confront the challenge of reinventing myself under conditions of constant, daily danger, where I would be forced to remain lucid and would learn to have control over how I spent my energy, which I was looking forward to; to achieve this, I counted on meeting, at least once more, Don Chente….

Horacio Castellanos Moya was born in 1957 in Honduras, where he lived with his Honduran mother and Salvadoran father for four years. Thereafter, the family lived in El Salvador. In 1969 Castellanos Moya left El Salvador to attend York University in Toronto. On a return visit to El Salvador, he witnessed the massacre by government snipers of twenty-one unarmed students and workers. He dropped out of college and left El Salvador to work in Mexico as a journalist. His sympathy with the rebel cause was destroyed by the spectacle of internecine conflict that became the curse of the movement. He returned to El Salvador in 1991, on the eve of the peace treaty that ended the conflict (like Erasmo in The Dream of My Return).

Advertisement

From 1991 to 1997, Castellanos Moya worked for literary periodicals and wrote four volumes of short stories, as well as the novels Baile con Serpentes (1996) and El Asco, Thomas Bernhard en San Salvador (1997), which resulted in death threats against Moya’s family. This unpleasantness led to a renewed exile of ten years, again in Mexico City. He continued to write short stories and novels and strengthened his bonds with other writers in exile, including Roberto Bolaño, who called him “the only writer of my generation who knows how to narrate the horror, the secret Vietnam that Latin America was for a long time.” Castellanos Moya was a writer in residence at various colleges during this period. Currently he teaches at the University of Iowa.

Moya is a bold and accomplished craftsman. The Dream of My Return is told in the first-person past tense. The vocabulary and phrasing fit Erasmo perfectly, just as the rambling, pages-long paragraphs accord with the obsessive sequences of self-questioning and out-of-control mental wandering he succumbs to in his reflections. Everything is clear. Those who criticized some of the first-boom writers for modernist self-consciousness (hence elitism) will have no complaints here. Castellanos Moya is a vernacular writer.

From novel to novel, Castellanos Moya varies his mode of attack. The She-Devil in the Mirror consists of nine separate unbroken paragraphs in the voice of an upper-class Salvadoran woman discussing, with a confidante, her version of a mysterious death. Tyrant Memory has another female narrator, present in a bricolage made from diary entries, standard past-tense narrative segments, and very long passages of naked dialogue. (Among contemporary male Latin American writers, Castellanos Moya is distinguished in the facility with which he writes about women.) Revulsion: Thomas Bernhard in San Salvador is a continuous, howling monologue about the fallen condition of El Salvador today, delivered to Castellanos Moya by a friend whose outrage resembles that of the great Thomas Bernhard.

The Dream of My Return was translated from the Spanish by the renowned Katherine Silver. When asked in an interview “What do you think should be the most important criteria in choosing books to translate into English?,” Silver replied, “Maybe that it be astonishing and that nobody is or could be writing anything like it in English.”

You can get out of breath reading Moya, who seems to have some occult command over the relationship between subject matter and the kinetics of the language chosen to present it in. There are no longueurs in his books.

Erasmo Aragon is not a superfluous man in the canonical mold of Turgenev’s hero in The Diary of a Superfluous Man. The literary woods are of course as full of superfluous men as they are of unreliable narrators and, these days, really rebarbative antiheroes. Superfluous men make up an illustrious lineage: Goncharov’s Oblomov, Dostoevsky’s Underground Man, Melville’s Bartleby, Robert Musil’s Man Without Qualities, all the way down through Sartre’s Roquentin and the hero of Ben Lerner’s debut novel, Leaving the Atocha Station. Superfluous men respond with disaffection, dysfunction, or withdrawal when they are unhorsed or irritated by the changing fortunes that the social machine spits out. It can be anything—plunging status, national disgrace, political or religious disillusion, extreme boredom.

Erasmo Aragon is his own variant on the type. He doesn’t keep going back to bed like Oblomov or turning down jobs like Bartleby. The concatenation of the specific events in his personal history has resulted in a dazed, feverish doggedness, in which state he systematically creates his own certain defeat. His critical consciousness is highly intermittent, you might say.

Do we need another superfluous man manqué? I think so. It’s always interesting to pick at the question of why these guys are the way they are. Sometimes the answer is on the surface and sometimes it’s complex and not on the surface at all. First of all, it’s fun to read about superfluous men. I don’t know exactly why. Maybe they offer to overworked and overbooked readers a dream of letting go, enjoying regression. There is learning and pleasure to be got from reading about them. (There is to my knowledge no parallel tradition of applying that nineteenth-century coinage to female characters: there is no category of “superfluous woman.”)

Erasmo’s characterological symptoms are typical in survivors of political terror and the post-traumatic stress it produces. Castellanos Moya knows that the characters in this book—which he takes from the more privileged sectors of Salvadoran society—have, for the most part, been spared the worst of the horrors that have occurred in their country. They may endure imprisonment—brief or not—and the perils of flight are real enough, and the experience of exile is often very rough. But they have escaped torture, rape, and death—they have money to get them out of town, money for false papers, friends in Miami, etc. They suffer nonetheless, and their lives bear the marks of that suffering. (Among the many formative memories in Erasmo’s life that are replays of Moya’s own is the blowing up of the front porch of his grandmother’s house.)

The new novel is a character study of one of the demoralized and still half-obtuse victims of past turbulence. Erasmo is unusually screwed up. What animates him is a sourceless conviction that going home again will remake him. He has just enough life force to continue putting one foot in front of the other as he prepares his return. But what is most alive in him is his sense of disconnection and disillusion and his utter rejection of the idea that a renovated left will make a difference in his future. The left is wholly deglamorized in Moya’s works. Here Erasmo is recalling Héctor, “a man who left Che in the dust as far as revolutionary adventures are concerned”:

Immediately after the triumph of that [Sandinista] revolution,…while the commandantes were still singing the refrain “implacables en el combate y generosos en la victoria,” “implacable in battle and generous in victory,” he, on his own initiative, paid a visit to several prisons and expeditiously executed all the officers and noncommissioned officers in the dictator Somoza’s defeated National Guard—only by terminating them immediately could a counterrevolution be prevented….

Moya is not simpleminded in the presentation of his characters, many of them casualties of American interventionism, some of them guilty beneficiaries of it. His scorn goes where it is deserved, to the left as in the vignette of Hector above—and as for the right, asked about the origins of “the curse of violence” in Latin America, this was his response in a 2008 interview:

The answer to this question is material for a book. I have no doubts that the politics of domination and plundering of the United States toward Latin America has played an important role in the recycling of violence, but it is not the only element nor do I think it is the historical origin of it…. The phenomenon was more complex, at least in the case of El Salvador: while the government of Reagan was giving millions of dollars in guns per day to the Salvadoran militaries so that they could commit the massacres against the population, it was within the United States itself that the biggest movement in solidarity with the revolutionary forces of El Salvador developed, a movement that contributed a lot of money. In literature things aren’t black or white; shades and paradox are almost always at the base of great art.

At the end of The Dream of My Return, the reader understands that Erasmo Aragon’s misadventures are fated to continue. His struggles to function in a medium of fear, paranoia, and deceit have led him into a novel kind of active passivity—passivity disguised as action.

Five novels as well as five collections of short stories by Horacio Castellanos Moya have not yet been translated into English. They should be.

This Issue

January 14, 2016

ISIS in Gaza

How to Cover the One Percent

A Ghost Story

-

*

A useful inclusion in any study guide for Moya’s oeuvre would be Douglas V. Porpora’s How Holocausts Happen: The United States in Central America (Temple University Press, 1990). The interlinked civil wars-cum-counterinsurgency massacres overseen and quartermastered by the United States in 1970s Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua have never been adequately recognized as what they truly were—a prolonged ethnocidal exercise in which an estimated 200,000 Indian peasants were killed or disappeared. Porpora makes the point that mass murder by the state was only one wing of this para-Holocaust, the other being the cruelly imbalanced agricultural systems enforced on the peasant populations by the overprivileged elites of these countries. There was a huge difference between upper and lower classes in the statistics for public health, infant mortality, and adult longevity. ↩