In Samuel Beckett’s novel Malone Dies the eponymous hero becomes obsessed with the idea of reciting a complete inventory of his worldly goods in the few moments preceding his death: a unique occasion, he feels, for producing “something suspiciously like a true statement at last.” Needless to say, despite Malone’s enjoying very few possessions, the reader understands at once that this last desperate bid for control will be beyond him. The world will not stay still, his memory is failing, and the moment of death, or rather the last moments of lucidity in which an inventory might be recited, are impossible to predict.

In Memory Theater, Simon Critchley’s hero, who would appear to be a fictional Simon Critchley, in that he shares the same curriculum vitae and publications as Critchley, has a more extravagant but related ambition: in the hours immediately preceding his demise he will embark on a virtuoso recall not only of his own life but of all the philosophy and history he has ever known.

At the instant of my death, I would have recalled the totality of my knowledge. At the moment of termination, I would become God-like, transfigured, radiant, perfectly self-sufficient, alpha and omega.

Critchley’s delirious alter ego has more energy than Malone and with the aid of a “memory theater,” an elaborate prompting mechanism, appears to have achieved his end, at least so far as the recall is concerned, only to discover that he is not going to die when expected. It was a false alarm. At this point he becomes more afraid of death than ever and the life that remains to him is one of terror and chronic, psychosomatic pain.

Much of Critchley’s work has been focused on death and contemporary attitudes toward it. Very Little…Almost Nothing (1997), written in the emotional turmoil after his father’s death, examines how one is to think of death in the absence of any religious or redemptive belief. There are long discussions of Maurice Blanchot, Beckett, and Wallace Stevens leading to the conclusion that if your desire for meaning remains essentially a desire for religious redemption, you will not find it, or any substitute for it, in literature. Critchley works on the assumption that many imagine the contrary.

The Book of Dead Philosophers (2008) opens with a denunciation of our desire either “to deny the fact of death and to run headlong into the watery pleasures of forgetfulness,” or alternatively to seek “magical forms of salvation and promises of immortality.” It is familiar criticism. To counter “our drunken desire for evasion and escape” Critchley offers philosophy, or rather Cicero’s notion that “to philosophize is to learn how to die,” an idea to be found in many of Critchley’s publications. He then proceeds to recount the lives and deaths of almost two hundred philosophers. Attractively dense, rich with anecdote and quoted aphorism, these mini-biographies seek to draw us to “the appropriate attitude to death”—a mixture of acceptance and curiosity—which is also, Critchley claims, a first step on the road to freedom and happiness, since it is our narcissistic terror of death that enslaves us and makes life unlivable.

The project is hard to fault and easy to read, yet here and there an uncomfortable tension emerges between announced purpose and actual performance. Take the twenty-two-line presentation of the Chinese philosopher Mengzi (372–289 BC), who is quoted as saying, “I desire fish and I desire bear’s paws. If I cannot have both of them, I will give up fish and take bears’ paws.” What exactly these two things might have meant for a Chinese in the third century BC we are not told, but Critchley explains that Mengzi is arguing by analogy that if, while desiring both “life and rightness,” one can’t have both, then “one should give up life and pursue rightness.” In a further quotation from Mengzi, Critchley’s “should” is left implicit:

Thus there are things that we desire more than life, and things that we detest more than death. It is not only exemplary persons who have this in mind; all human beings have it. It is only that the exemplary persons are able to avoid losing it, that is all.

That the common man’s hierarchy of values, at least at an early age, might not put life first is an interesting reflection and would seem to be in line with Critchley’s goal of encouraging us to accept death rather than cling to life at all costs. Yet he comments, wittily and dismissively: “As a non-exemplary person, I’ll take fish and life and politely pass on rightness and bears’ paws.” We hear no more of Mengzi, not even his death.

This is not an isolated incident. From time to time, it seems, Critchley is prey to what in a more recent publication he calls a “smart-alecky reaction” that seeks complicity with the reader at the expense of something, or someone, made to seem pompous and, in Mengzi’s case (given our unfamiliarity with bears’ paws), slightly ridiculous. Beneath, or alongside, the surface moralizing, it is important that writer and reader feel clever together. So if death is made easy to face in this book it is because much of our attention is held by the author’s sprightly exposition. Concluding a forty-line section entitled “Zen and the Art of Dying,” he enthuses over this droll excerpt from a monk’s “death poem”:

Advertisement

Till now I thought

That death befell

The untalented alone.

If those with talent, too,

Must die

Surely they make

Better manure.

Critchley describes this as “wonderfully self-deprecating.” I’m not so sure. In any event it is entirely in line with the conflicted process of denouncing narcissism, while celebrating it in extremis. And this, very largely, is what Memory Theater is about.

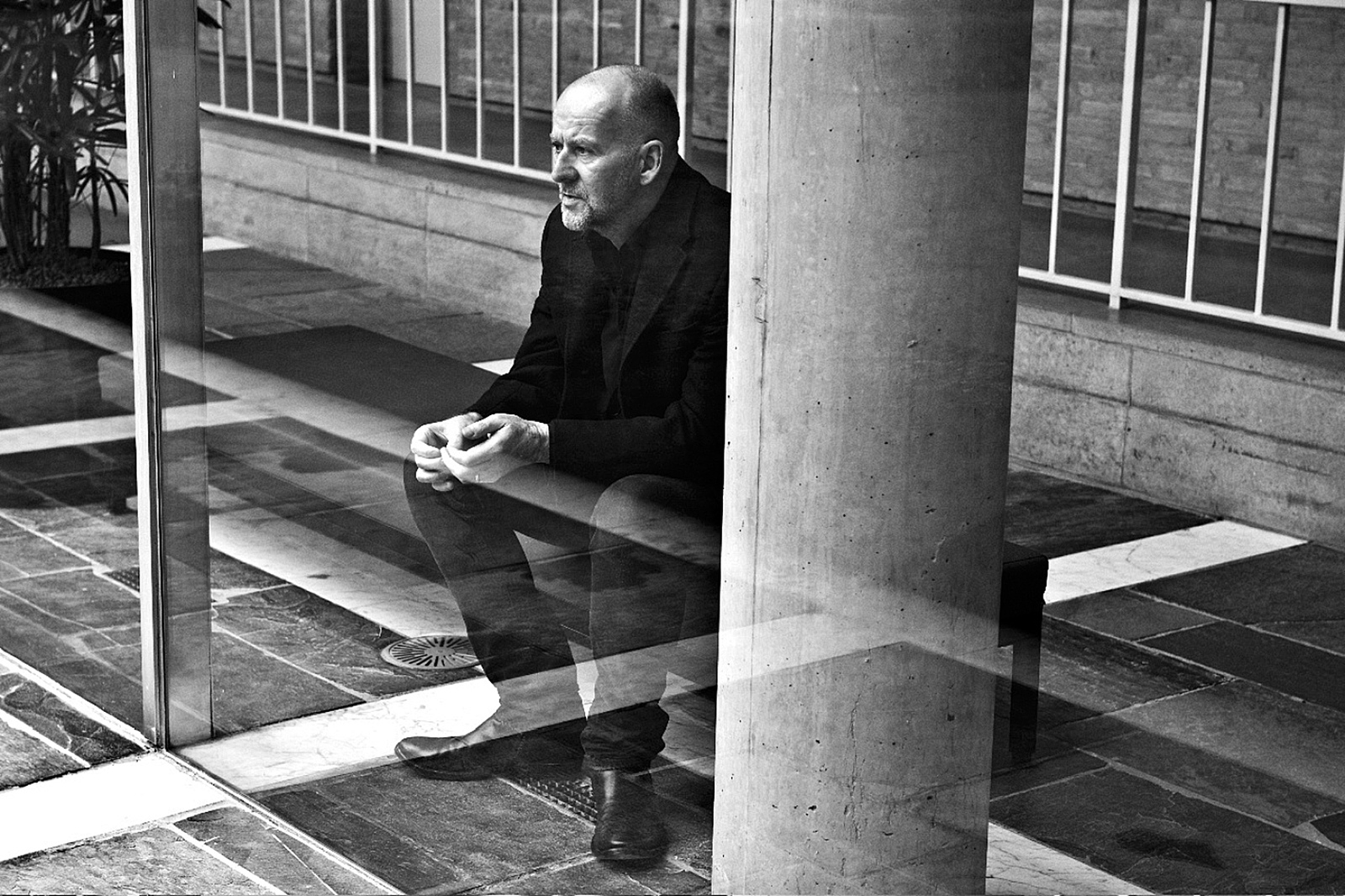

There is always a sense of great promise when a scholar trained in philosophy turns to the novel. Narrative is to be focused on the exploration of ideas; ideas are to be tested in the arena of circumstance and personal relations. This will be stimulating, perhaps enlightening. In Memory Theater, Critchley gives us only one character, his alter ego; what happens in the book happens largely because of this character’s self-obsessed isolation. “I hate myself,” Critchley remarked last year in an interview. “That much should be obvious.” And again: “I wrote the book to try to correct that tendency in myself which of course you fail to do but nonetheless you have to try.”

This brings us to an interesting complication present throughout Critchley’s work: the reader is never sure whether the criticism so uniformly leveled at society doesn’t actually spring from the author’s dissatisfaction with himself. Yet if the project of self-correction through writing is known to be doomed to failure, why does one “have to try”? It would seem common sense that the more brilliantly, even humorously, one describes one’s own self-obsession, the more self-obsessed one risks becoming. This is the territory of itching and scratching.

Memory Theater’s narrator and hero, then, is a British philosophy professor who, having moved to the US, returns briefly to the UK to clear out his office, where, rather mysteriously, he finds he has been sent a stack of boxes containing the papers of the now deceased Michel Haar, an old friend and former philosophy teacher. The tone of the writing is vaguely Sebaldian, the plotting typical of an Eco novel, with the same combination of erudition and the occult, the same threat or promise of hidden truths that will overturn our received understanding of the world. “Perhaps…a kind of pastiche,” Critchley observed in an interview.

The boxes bear the names of zodiac signs. Conveniently, they allow themselves to be unpacked in such a way that Critchley, commenting on Haar’s papers, can nod with affection and humor to his own interests in Nietzsche, Heidegger, Derrida, Sartre, Lacan, and many others, before focusing on the history of the so-called memory theater, an idea that Haar had apparently become obsessed with in the 1960s. Drawing on the Renaissance scholar Frances Yates’s account of early modern strategies for memorizing vast quantities of knowledge, Critchley introduces us to the idea of buildings whose architecture and internal arrangement were designed to store and/or stimulate recall of masses of information, the promise being that “through techniques of memory, the human being can achieve absolute knowledge and become divine.”

Having suffered, early in life, like Critchley himself, from a traumatic accident that led to the loss of much of his childhood memory, our narrator is unduly excited by these wild speculations. “My self felt like a theater with no memory,” he says of the aftermath of the accident. Consequently, he begins to think of all major buildings as memory theaters: Gothic cathedrals with their images of the Bible story are memory theaters; Shakespeare’s Globe with its zodiac signs above the stage was a memory theater; even modern cities in their entirety are nothing other than vast prompts for the memory. Haar was convinced, we discover in the next box our narrator opens (whether there is some subtle connection between the discoveries of each box and the zodiac sign it bears, I couldn’t say), that Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit was a sophisticated memory theater in book form, where rather than simply memorizing information, all manifestations of the human spirit would appear before the reader who, by internalizing them, would achieve maximum realization of the self’s potential.

Critchley is effective and funny at showing how easily an intellectual can fall into the most fantastical delusions so long as they appear to have some textual support in the world of his peers. It is strange, perhaps, that little attempt is made to say how memory works or to distinguish between the status of personal memory and bookish memory, but this is perhaps because our hero is entirely committed to the world of books, philosophical books, and to self-affirmation through writing toward others like himself. Isolated he may be socially, but he is nevertheless an initiate in a learned community. Readers in the know will pick up on all kinds of allusions, undeclared quotations, intertextuality, and so on (which Critchley has discussed at length in interviews online). Others may feel a little left out and constantly, perhaps entertainingly, uncertain as to whether the novel’s references are factual or not.

Advertisement

Michel Haar, for example, the French philosopher, really exists, or existed, though he did not have all the interests Critchley ascribes to him. But what does our narrator mean when he speaks of his “necronautical activities”? What is this about? The vast memory theater that is Google resolves the problem: Critchley is a founding member, together with his friend the novelist Tom McCarthy, of the International Necronautical Society, a semiserious club that seeks “to bring death out into the world,” and engages in playfully provocative debates on aesthetics. Essentially, the statements on the club’s website encourage us to pay attention to matter as matter and to avoid as far as possible distorting or romanticizing it with form or ideas (in 2005 Critchley published Things Merely Are: Philosophy in the Poetry of Wallace Stevens). “The aim,” reads a typical statement, again from the Necronauts’ site, “is not contemplation. It is to stuff inauthenticity into our mouths like Molly Bloom’s seed cake, and thus with a silent ‘yes’ to reaffirm the tenets of necronautical materialism.”

Joyce is frequently mentioned or alluded to in Critchley’s work and in the interviews he gives. The hero of Memory Theater, we discover, “perused” a few pages of Ulysses each evening “in the exquisite, clothbound 1960 Bodley Head edition” before going to bed. Perhaps some readers will be familiar with that edition. Ulysses was also a memory theater. Memory Theater, the novel, is itself a kind of memory theater, bringing together all Critchley’s previous work and interests. Many of the quotations it offers are repeats of those in earlier publications. At one point The Book of Dead Philosophers is mentioned. “It was funny, full of impressively wide reading, and utterly shallow,” the fictional Critchley comments. Perhaps a “wonderfully self-deprecating” remark.

At the bottom of the last box the narrator finds the papers that launch the plot proper, “a series of circular charts covered with numbers, dates, and masses of cramped handwriting.” “I felt a chill, as if someone had walked over my grave,” the narrator tells us. Much research and erudition lead to the conclusion that Haar had discovered a way of combining the astrological birth chart and the memory theater, the intention being “to plot the major events in a philosopher’s life and then to use those events to explain his demise.” Despite the fact that “much of the script was simply illegible,” peppered with “vaguely occult-like geometrical designs,” the narrator nevertheless establishes that Haar had accurately predicted his own death date together with those of many of his then-living colleagues, Derrida, for example, refining astrological prediction with the momentum, as it were, of a person’s past actions. Critchley’s own name is on one of the last charts to surface. He will die of a stroke on June 23, 2010, in the Dutch village of Den Bosch.

All this occurs in 2004. “Like Wittgenstein receiving word of his terminal cancer,” the narrator is initially more relieved than depressed, returning to his job in the US and publishing the books that Haar’s chart of his life predicted he would publish. Then in 2008 he mysteriously receives another box, the Taurus box, which had been missing from the original five.

It contains a scale model of the memory theater that Giulio Camillo designed in the early sixteenth century, a curious building in which a lone spectator on a stage was to be aided by carefully organized statues in the “audience” to recall all human learning. At this point our hero falls into serious mental difficulties, experiences bizarre visual and auditory hallucinations, suffers from severe tinnitus, and grows paranoid to the point of believing that his computer is attacking him. The lengthy descriptions of this suffering, like the book’s opening account of the author’s insomnia, carry a ring of truth, or at least urgency, immediately distinguishable from the elaborate contrivance of the plot. There are occasions when it seems that a genuine psychological unease is being not so much expressed in this novel as hijacked by the literary form imposed, a curious state of affairs given the necronautical injunction to forget form and let things be what they are.

What follows is the melodrama or comedy of the narrator’s journey to his supposed death place, his construction of a life-size memory theater based on Camillo’s design, and his preparation for the great day, which of course the reader knows will not be the day of the author’s death, otherwise he could hardly be narrating the present book. The theater floor is divided into seven levels intersected by seven gangways, these to represent the seven planets, as they were when Camillo designed the building:

Rows three to five were devoted to the history of philosophy. I arranged matters chronologically in a series of obvious clusters: (i) the Pre-Socratics, (ii) Platonists and Aristotelians, (iii) Skeptics, Stoics, and Epicureans, (iv) Classical Chinese Philosophers, and so on.

It is the same arrangement as the chapters of The Book of Dead Philosophers. There are moments of wry comedy, as when “the great Liverpool Football Club teams of the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s” are recalled alongside national boundaries before and after World War II, but overall the evident silliness of the venture, which seems more a caricature of a control obsession than its exploration, together with the fictional Critchley’s pleasure in piling up the cultural references, is discouraging.

Why does the narrator not die, if all Haar’s other predictions turned out to be accurate? We are not told. Critchley leaves his alter ego waiting for the local Den Bosch library to open so he can begin research for the construction of a new, more flexible and ambitious memory theater that would “reach down into the deep immemorial strata that contain the latent collective energy of the past. The dead who still fill the air with their cries.” The greater hope, of course, would be that he might meet a sweet librarian. As Critchley has said in an interview: “Memory Theater describes a solitary and dead world devoid of love. I do not want to live in that world, though I have often found myself oddly at home in it.”

Since Memory Theater came out in the UK, Critchley has published a short e-book, Suicide. “My intention,” he tells us, “is to give a defense of suicide,” to “open up a space for thinking about suicide as a free act that should not be morally reproached.” In what appears to be an upward curve of self-exposure throughout his oeuvre, this project is then complicated by a declaration of personal interest:

For the first time in my life, I have found myself genuinely struggling with thoughts of suicide, “suicidal ideation” as it is unhelpfully named. These thoughts take different forms, multiple fantasies of self-destruction, usually motivated by self-pity, self-loathing and multiple fantasies of revenge.

The author then proceeds with a reflection on suicide notes that, far from defending suicide, becomes an analysis of the relationship between self-hate and self-love in the classically Freudian understanding of narcissism. It’s not clear at this point whether the purpose of the project is to criticize the suicidal person’s malaise or defend his right to choose to die.

Finally, after rehearsing the usual arguments for and against the legitimacy of suicide, Critchley seeks escape from suicidal thoughts through the kind of experience he finds described in To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf, who, of course, would later kill herself.

Always, Mrs. Ramsay felt, one helped oneself out of solitude reluctantly by laying hold of some little odd or end, some sound, some sight. She listened, but it was all very still; cricket was over; the children were in their baths; there was only the sound of the sea. She stopped knitting; she held the long reddish-brown stocking dangling in her hands a moment. She saw the light again. With some irony in her interrogation, for when one woke at all, one’s relations changed, she looked at the steady light, the pitiless, the remorseless, which was so much her, yet so little her, which had her at its beck and call (she woke in the night and saw it bent across their bed, stroking the floor), but for all that she thought, watching it with fascination, hypnotized, as if it were stroking with its silver fingers some sealed vessel in her brain whose bursting would flood her with delight, she had known happiness, exquisite happiness, intense happiness, and it silvered the rough waves a little more brightly, as daylight faded, and the blue went out of the sea and it rolled in waves of pure lemon which curved and swelled and broke upon the beach and the ecstasy burst in her eyes and waves of pure delight raced over the floor of her mind and she felt, It is enough!

Attention to the present moment and immersion in the natural world around us offer a way out of self-obsession and depression. Critchley finishes his brief book on a high as he describes a similar moment of his own:

When life stands still here and we face the endless, shifting, indifferent grey-brown sea, when we hold ourselves open out into that indifference tenderly, without pining, self-pitying, complaining or expecting some reward or glittering prize, then we might have become, just for that moment, something that has endured and will endure, someone who can find some sort of sufficiency: right here, right now.

At this point our author sounds exactly like the teacher at a meditation retreat, which I do not mean as a criticism, though Critchley might not wish it as a compliment. However, while the teacher of meditation offers an antique discipline that fosters this attention to the matter-of-fact present, Woolf, arguably, and Critchley too, perhaps, are returned to self-obsession precisely by the business of evoking the therapeutic experience in such elaborate and ambitious prose.

“Perhaps the closest we come to dying,” Critchley claims toward the beginning of Suicide, “is through writing. In the sense that writing is a leave-taking from life, a temporary abandonment of the world and one’s petty preoccupations in order to try and see things more clearly.” I fear this is not the case. Rather it is through writing that writers assert themselves in the world, measure themselves against their peers, and seek to consolidate their selfhood. Never is the writer more alive than when he is writing, more prone to self-love and self-hate, even when regretting narcissism and wishing he was free of it. So the very neatness with which Suicide ends, its intense straining for literary effect, undercuts the message it means to send.

This Issue

January 14, 2016

ISIS in Gaza

How to Cover the One Percent

A Ghost Story