The Tale of Genji, scenes from the emperor’s court in eleventh-century Japan organized around the amorous adventures of its hero, Prince Genji, goes deeper than any romance. The main characters, the radiant prince in particular and a number of the women he beguiles, are endowed with a range of emotions sufficiently complex to make them seem true to life even to the modern reader. There is no precedent in Japanese literature for the author’s vision of the storyteller’s task. Speaking through Prince Genji, she makes a case for realism, the gateway to what we consider the modern novel:

There are moments when one wants to pass on to later generations the appearance and condition of people living in the present—both the good and the bad…. In either case, you will always be speaking about things of this world…. In the end, the correct view of the matter is that nothing is worthless. [Italics mine]

Claims that the tale is “Proustian” are perhaps extravagant, but the notion that fiction must aspire to more than punishing vice and rewarding virtue was centuries ahead of its time.

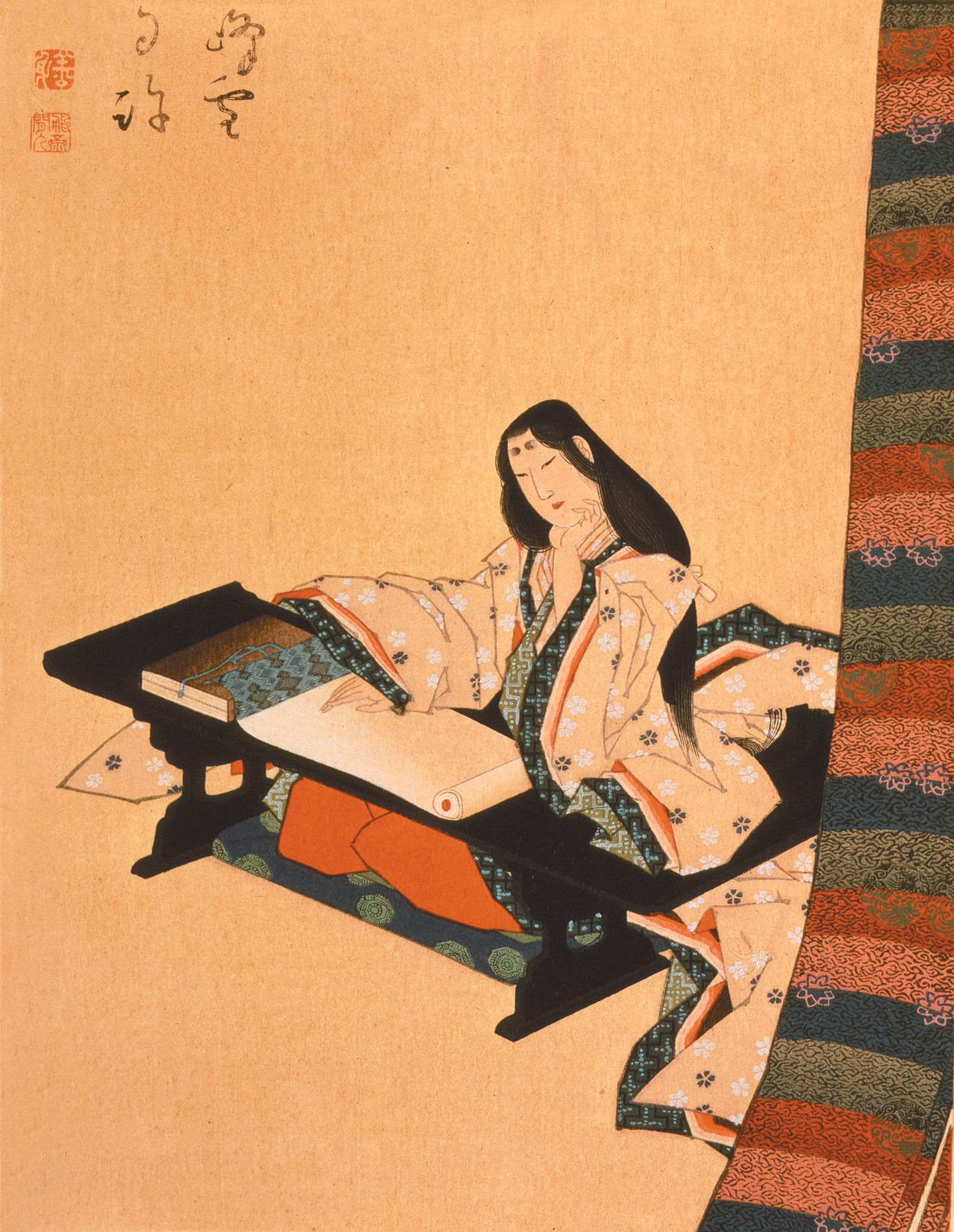

The author was a noblewoman from a minor branch of the dominant Fujiwara clan known to readers as Murasaki Shikibu. (Murasaki, “lavender,” is the sobriquet she gives her favorite, and the most sympathetic, female character, the love of Genji’s life; Shikibu, the “Ceremonial Office,” was a post her father held.) Born around 973, briefly married and widowed in 1001, she is thought to have worked on her voluminous manuscript from about 1002 until the time of her death, estimated at 1014. It is clear from the text, rich with allusions to the Chinese literary canon and earlier Japanese poetry, that she was uncommonly literate for a woman of her era. Her book tells us moreover that she understood minutely the social and political dynamics of court society and was a subtle, witty, sometimes ironic portraitist. What she chose to reveal about Prince Genji, who is always magnificent but not necessarily admirable, conveys an ambivalence about her hero. The reader is tempted to think of her, together with her more acerbic contemporary, Sei Shōnagon, as Japan’s earliest feminist.

Genji addresses his thoughts on the art of fiction to a young woman he wants to seduce. Since he is supposed to be looking after the girl as her surrogate father, his excitement is shocking even for a heroic womanizer. Like a child seeking approval from his mother, he hints at his feelings to his dearest consort, Murasaki, the author’s namesake, and she sees through him in a flash and reproves him in her gentle way:

“She may be ‘quick to grasp things,’ as you put it, but if she lets her guard down and innocently puts her trust in you, she’ll regret it for sure.”

“And why wouldn’t she put her trust in me?”

“You ask why? Your amorous proclivities, which have so often brought me unbearable heartache, remind me why time and time again.” She smiled.

One page later, undeterred by the girl’s distress and careful not to alert the hovering ladies-in-waiting, Genji “quietly slip[s] off his outer robe, skillfully muffling the rustle of his soft, unstarched summer clothing, and [lies] down beside her.” It is unclear how far he goes on this occasion, but his ward is distraught. Like many of his indiscretions, this ends tragically. In despair, the girl succumbs to the blandishments of a powerful lord who installs her in his palace, humiliating his principal wife and driving her to madness.

Genji’s concupiscence is a disagreeable flaw in what is otherwise an idealized portrait of manhood according to the ideals of the day. Murasaki set her story during the years when she was at court, the late tenth to mid-eleventh century, a verdant season in Heian-period history, when the arts were in full blossom and elegance was among life’s principal pursuits. Genji is ravishingly handsome, his attire the most tasteful in the room, the lingering aroma of his robes dizzying; he is well versed in the Chinese classics, an accomplished poet, musician, dancer, painter, and an exquisite calligrapher. But once he has been aroused, he will not rest until his desire has been gratified. Unlike Don Juan, he isn’t boastful about his success with women of every category. In fact, he never forgets a woman he has seduced; when he has ascended to the zenith of his power at court, he orders the construction of a new annex to the east of his villa, four interconnected wings, one for each season, and installs in each wing a woman from his past whom he has pledged to look after for life, including even a lady with a bulbous red nose.

Advertisement

Genji’s intemperate appetite would repel today’s reader even more than it does if the author hadn’t bestowed on him an awareness of his cupidity. Time and again he laments his behavior and its dire consequences:

He realized that his disposition had not changed, that it was still his nature to be tormented by overwhelming amorous impulses…. A person’s karmic destiny may be unpredictable, but there was no denying that he had only himself—not the actions of another—to blame for what had happened.

But he cannot help himself. There is something sympathetic, proto-modern even, about a mostly idealized hero battling his demons in vain: Genji emerges not as an exotic figure so much as a familiar everyman caught in a trap of his own making.

According to Shingon (True Word) Buddhist doctrine, which was predominant in the Heian court, karmic retribution for illicit behavior was exacted in this lifetime. Transgressors, like the young noble who has his way with Genji’s wife, often die of shame, or, if they are women, seek refuge from reality in monastic vows. That Genji himself will be punished is inevitable, and his punishment turns out to be the cruelest kind, visited upon the person he loves most in the world. In Chapter 40, Murasaki sickens and dies, and the circumstances of her death imply that she is being made to suffer for his sins: as her illness worsens, she is possessed by the vindictive spirit of a neglected mistress from Genji’s youth. Frantic, he orders an exorcism but to no avail. He knows that his inconstancy has been a torment to Murasaki, and her loss is more than he can bear. He secludes himself, turns visitors away, and disappears from the pages of his story though it is far from over. The chapter is titled “The Law” (in Dennis Washburn’s augmented translation, “Rites of the Sacred Law”), a chilling allusion to the inexorability of karma.

The ten chapters that follow chronicle a rivalry in love with tragic consequences. The main characters are Genji’s grandson, Niou, and Prince Kaoru, putatively Genji’s son but actually the offspring of his wife and her seducer. These inept lovers compete for the affections of two sisters and manage to destroy them both.

The author’s reason for extending The Tale of Genji beyond the hero’s death is clear from the line that opens the concluding section of the tale: “With Genji’s radiance extinguished, not one among all of his descendants shone with the same glorious light.” Observing the two rivals pursue their passion, a comparison that finds them inferior to Genji in every way is unavoidable. Kaoru in particular, half a millennium before Hamlet, though dazzling to the eye, can be considered Japan’s first antihero, oversensitive, paralyzed by doubt, ineffectual. His story implies that this transitory world, deprived of Genji’s radiance, has darkened, moved closer to, in the Buddhist sense, the end of days.

The difficulty of translating the Genji begins with how impossibly hard it is to read.1 Heian-period Japanese was distinctive and short-lived: two hundred years after it was written, the text was already close to undecipherable to even the most literate native readers and had to be heavily annotated. To modern Japanese readers, the Genji in the original is a largely unsolvable puzzle. The “national language” textbooks used in high school still include one or more famous passages that students are required to parse their way through, and at least one passage requiring “explication” predictably appears on college entrance exams. For the most part, though, Japanese readers sample the Genji in modern-language translations or, more commonly, comic-book (manga) versions.

For those of us who have done battle with Japanese as a foreign language, deciphering, not to mention interpreting, the Genji is a disheartening challenge. Conversancy with the modern language is requisite, but by itself is hardly adequate to the task: Heian-period Japanese and the modern language are separated by a vastly greater distance than separates Chaucerian or, arguably, even Old English from our modern language. At the heart of the problem is an intrinsic vagueness. Linguists will offer various, contradictory explanations for this depending on their bias. But surely the bewildering absence of clarification in Murasaki’s prose is partly due to the homogeneity of the community of original readers. The scale of life at the court was miniature. Nobles rarely ventured beyond the confines of the capital.2 They watched the same pageants and participated in the same ceremonies, processions, and rituals; they read the same books, romances, and, mostly for the men, the Chinese classics; they were frightened by the same superstitions. Over time, a commonality of limited experience generated a mode of expression that was liberated from the burden of explanation.

Advertisement

One example will suffice. There is no shortage of personal pronouns in the modern language, which has at least five words for “I” and more than five for “you,” each conveying subtly different shadings of rank and status as perceived by the speaker (Japanese remains in essence a feudal language). Heian Japanese, on the other hand, uses no personal pronouns and frequently omits names. The question who is addressing whom must consequently be intuited from context, with some help, rarely adequate for the average reader, from the agglutinated verbs that drop into place at the end of dismayingly long sentences and contain, in addition to tenses and modes, verbal suffixes that signal the rank and status of the speaker vis-à-vis the personage being addressed.

Given the bewilderment that this and a host of other uncertainties create, it is surprising to learn that Murasaki may have read aloud from her work in progress to other ladies-in-waiting at the court. Apparently, the contemporary reader/listener required only slender hints to keep herself on course through the implicit emphases of the text. Even Tanizaki Jun’ichirō, the canonical twentieth-century story-teller, acknowledged the difficulty, when translating the Genji into modern Japanese, of preserving “that indirect manner of speaking, fraught with implications, yet so understated that it can be taken in several different senses.” In the end, Tanizaki, who created not one but three modern-language versions of the Genji, concluded that he was unable to achieve the economy of Murasaki’s Japanese: “If we posit that the original expresses ten units of meaning using five units of expression, then I have expressed them with seven.”

In view of Tanizaki’s failure by his own account to mirror Murasaki’s language in modern Japanese, a language with its own genius for ambiguity and obfuscation, what chance of success can a translator hope for in English with its inherent demand for the specific? Consider the implicitness of the decisive moment in Chapter 9 when Genji, twenty-three, consummates his relationship with the thirteen-year-old he calls his “little Murasaki.” Here is a version as literal as I can manage (I am not proposing this as a satisfactory translation but simply indicating what is written):

In all that time, when he had no such thoughts in mind, everything about her struck him as merely adorable, but now he could no longer endure, though he did feel sorry for her—what can have happened?—though their relationship wasn’t of the sort that would allow others to distinguish a change, there came a morning when he rose early and the girl remained abed.3

Here is the passage in Dennis Washburn’s translation:

For several years he had driven all thoughts of taking her as a wife out of his mind, dismissing her talents as nothing more than the accomplishments of a precocious child. Now he could no longer control his passion—though he did feel pangs of guilt, since he was painfully aware of how innocent she was.

Her attendants assumed he would consummate their relationship at some point, but because he had always slept with her, there was simply no way for them to know when that moment would come. One morning Genji rose early, but Murasaki refused to get up. [Italics mine]

The phrases I have italicized do not appear in the original; they are amplifications the translator has felt obliged to make. Needless to say, in clarifying, he has moved some distance from Murasaki’s implicitness. Edward Seidensticker’s unembellished rendering, from the 1978 edition of his translation, is closer to the original:

He had not thought seriously of her as a wife. Now he could not restrain himself. It would be a shock, of course.

What had happened? Her women had no way of knowing when the line had been crossed. One morning Genji was up early and Murasaki stayed on and on in bed. [Italics mine]

A few lines below, the author moves into the child’s mind and another, related facet of the problem is revealed. Murasaki’s mother tongue was pure Japanese, unenriched by the compounds imported from China that would significantly augment the native vocabulary. While capable of subtlety, her vocabulary is, nonetheless, simple; a limited number of adjectives are used repeatedly to convey a broad spectrum of connotions. Omoshiroshi, for example, which may appear numerous times on the same page, can mean “interesting,” “comical,” “refreshing,” “eccentric,” “stylish.” Natsukashi (a translator’s nightmare) ranges from “enthralling” to “adorable,” with “captivating,” “nostalgic,” and “irresistible” in between. Namamekashi extends along a continuum from “vibrant,” “youthful,” and “elegant” to “suggestive” and “lascivious.”

Faced with an overwhelming variety of possible definitions, how far afield can the translator go without obliterating Murasaki’s wondrous simplicity? Tanizaki recognized the challenge: “I have endeavored to keep my vocabulary small.” In his introduction, Washburn acknowledges that “the description of settings or of the emotional states of the characters may seem repetitive and limited,” and adds, “I have tried not to go too far with the use of synonyms for the sake of lexical variety.” That sounds just right, but the choice of words he embeds in his heavily supplemented pages suggests he has not succeeded in avoiding what he calls “the thesaurus effect.” Here is how he handles the child’s interior monologue:

It had never crossed her mind that he might be the kind of man who harbored such thoughts about her, and she burned with shame when she recalled their sordid first night: How could I have been so naive? How could I have ever trusted a man with such base intentions?

This not only distorts but seems tonally wrong. There is no mention in the original of “burning with shame” or being “naive,” and certainly no reference to a “sordid night.” Washburn tells us that he relies “on narrative context to suggest the fuller nuances of this sort of vocabulary.” But the reader must wonder what a young girl knows of “sordid.” The author’s choice of adjective here connotes a wide range of meanings that default to “disagreeable,” or, in the parlance of a teenage girl, “yucky.”

Seidensticker also amplifies, but more moderately: “She had not dreamed he had anything of the sort on his mind. What a fool she had been, to repose her whole confidence in so gross and unscrupulous a man.” And Royall Tyler, in his 2001 translation, comes closest to getting it right: “She had never suspected him of such intentions, and she could only wonder bitterly why in her innocence she had ever trusted anyone with such horrid ideas.”

Then there is Arthur Waley:

That this was what Genji had so long been wanting came to her as a complete surprise and she could not think why he should regard the unpleasant thing that had happened last night as in some way the beginning of a new and more intimate friendship between them.

This is lovely, but more Waley than Murasaki. I’ll consider in a moment whether, in some cases, that is acceptable.

Observing the misrepresentations translators of the Genji seem unable to avoid brings me to the question of style, or, put another way, of conveying Lady Murasaki’s voice. If the translator’s goal is to create an equivalent to the original, what Washburn calls an “analogue,” then surely a critical first step would be hearing accurately, discerning how the author sounds. But perceiving style in an eleventh-century author writing in a language as vague and minimal, as utterly foreign as Heian Japanese, is no simple matter. Moreover, identifying her style and what constitutes its uniqueness is only the first hurdle; the translator must command his own language with sufficient mastery to reproduce or simulate what he has recognized.

The chances of a magical transformation occurring are further reduced when the translator subscribes to the notion that he must be invisible so that the reader, in Washburn’s words, “may experience the original in an unmediated way.” This turns out to be a paradox: in the absence of a visible translator, the author will also be invisible. Without style, in other words—and style is inevitably intrusive, not just visible—a translation cannot hope to convey the voice of the original author. Making my way through Washburn’s translation, I am struck by the absence of style. The result is a pervasive neutrality, a flatness lacking texture and resonance. In fairness, I find the other post-Waley translations of the Genji more or less disappointing in the same way.

The question remains: Do English readers need yet another Genji translation? Washburn explains that his principal motivation for undertaking this intimidating task was

precisely because there can be no such thing as a definitive translation…. I believe it is only through multiple translations of brilliantly complex and historically influential narratives like Genji monogatari that we can “get at” a source work in another language….

This notional justification, that the original emerges only in the sum of its translations, invokes the essay that has been enticing and confounding translators ever since Walter Benjamin published it in 1923, “The Task of the Translator.” Perhaps, as Benjamin would have it mystically, the life of the original achieves its ultimate destiny only in collaboration with the translations that succeed it; and perhaps each subsequent attempt is properly seen as a shard of the complete vessel that will comprise the “reine Sprache” (pure language) to which all language aspires since Babel. But even if we allow that Benjamin makes sense, surely the “shards” must be memorable in their own right. Alas, I am unable to feel that Washburn’s version emits a light of its own sufficient to make its presence on the Genji shelf imperative. In particular, the “radiance” of the original is dimmed by the narrative stenosis he creates with his excessive, and sometimes uninspired, amplifications that result in fattening Murasaki’s spareness—“blindingly shameful,” for instance, when “awkward” would have served.

I’ll also note that Washburn has not provided the reader with a list of characters or genealogical tables. This is particularly regrettable in view of his decision to identify characters by their titles, which change as the saga progresses, instead of names, requiring readers to puzzle out who the “Major Captain” or the “Major Counselor” might be. Inasmuch as all his predecessors have included guides to following the tale, the omission is curious and irritating.

I have done enough translating from Japanese to appreciate Washburn’s monumental effort; I admire him for having had the courage to undertake the task and the discipline to see it through. Even so, if I were obliged to rank the translations in English, I would place his at the bottom of the pile, beneath Royall Tyler’s spare version and Edward Seidensticker’s perverse, nonetheless distinctive, effort.

Which leaves Arthur Waley. There is no question that the Waley version is problematic: he cut and expurgated with abandon, deleting, among other things, the only example of Genji’s bisexuality. Moreover, his readings are often mistaken, and there are passages that turn out to be, on comparison with the original, his own invention. Even so, Waley, a member of the Bloomsbury group, was a genuine poet and a splendid stylist, and he managed to imbue his Genji with a distinctive sound, a voice that we are pleased and relieved to accept in lieu of Murasaki’s own. One recalls Borges’s “The Enigma of Edward Fitzgerald”: adjusting the enigma to fit the Genji, we discover a collaboration between a Japanese lady-in-waiting in the eleventh century and an eccentric Englishman in the 1920s that ushered forth a resonant English masterpiece with the heart and soul of ancient Japan. No translation since has come close.

This Issue

January 14, 2016

ISIS in Gaza

How to Cover the One Percent

A Ghost Story

-

1

Dennis Washburn’s new translation is the third complete Genji to appear in English since Arthur Waley published his version in six volumes between 1925 and 1933. ↩

-

2

The fishing village called Suma, to which Genji briefly exiles himself, is described as desolate and remote but is actually a mere fifty miles from Kyoto. ↩

-

3

For a measure of the degree to which pop culture has vulgarized the classical sensibility, have a look at the best-selling comic book Genji in seven volumes. The panel illustrating this exquisitely unarticulated moment is a lurid close-up of the young virgin’s hand clutching at the air in a spasm of passion. ↩