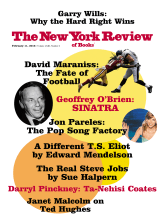

The Frank Sinatra centenary has brought forth an inevitably immense array of monuments and keepsakes. These have included Sinatra: All or Nothing at All, a four-hour documentary by filmmaker Alex Gibney; a comprehensive multi-CD survey of his broadcast performances, Frank Sinatra: A Voice on Air, 1935–1955 (Columbia/Legacy), including many previously unissued tracks, along with a good deal of promotional blather and forced banter from the Golden Age of Radio; two illustrated volumes, Sinatra 100 (Thames and Hudson), with text by Charles Pignone, and an almost dangerously weighty limited edition called simply Sinatra (ACC Editions), which between them unload an archive’s worth of Sinatra as photographic object, a revealing study in itself of just how, seemingly without effort, he could project a fully formed identity in almost any shot, and how multifarious are these identities when laid side by side, a whole population of alternate Franks.

There is also a deluxe edition, likewise limited, of Gay Talese’s celebrated Esquire profile Frank Sinatra Has a Cold (Taschen), which achieved classic status in describing not the man head-on (Sinatra had declined to be interviewed) but the atmosphere surrounding him, a roundabout method of realizing the most elegantly acute of portraits; and the poet David Lehman’s engaging, playful, deeply personal, and elegantly concise tribute Sinatra’s Century: One Hundred Notes on the Man and His World, published by Harper this past October—to cite only a few of the tie-ins, whether new or newly reissued.

Contemplating all this evidence of what Sinatra left behind leaves open the question of what remains of him a century after his birth. What will he come to signify for those born too late to have experienced how thoroughly he pervaded the culture, not only as a singer and actor but as a presence all the more powerful for the contradictions he so flagrantly embodied? Looking closely at Sinatra doesn’t make the pieces of his life cohere any better. By casting his book in the form of a hundred disparate observations, Lehman acknowledges how Sinatra’s singular image tends to break apart into separate facets, describing him as

a wounded swinger who could consort with gangsters but also liked to paint, won a Grammy for album design, took quality photographs of a ballyhooed prize fight for Life, and treated a popular song written for the masses as if it were a sonnet meant for patrician ears.

Listening to Sinatra at his peak singing “Close to You” (1956) or “Angel Eyes” (1958), you can have the illusion that nothing exists but his voice and the instruments that frame it, a closed universe of warm feeling, with an undertone of hurt made uplifting by the precision and grace with which each note and syllable is shaped. Here for once, at least until the turntable stops spinning, everything comes together in one place. Sinatra’s impatience was legendary—he found it hard, for example, to endure the perpetual delays of moviemaking—but at his best he sings as if he had all the time in the world, time enough to let the song unfold until it fills all space.

That unitary, fully shaped experience shatters the moment you step back and contemplate the man in all his aspects, so that those who try to sum up Sinatra—and everyone who ever crossed his path seems to have made the effort—fall back on contraries: he was tender and rough, vulnerable and domineering, boundlessly charitable and infinitely rancorous, a lover of string quartets and an admirer of mobsters, the most serious of artists and a childish prankster, perfectionist (in the recording studio) and perfunctory (on movie sets, more frequently as he went on). He was a singer who could evoke with aching persuasiveness a monogamous devotion quite foreign to him, a hothead who could look like a model of cool, gregarious by compulsion and solitary by nature. Among all those shifting appearances, where might the center lie? An anonymous friend, who may have been Sinatra’s longtime songwriter Sammy Cahn, ventured, in a statement notable for its studied absence of judgment: “There isn’t any ‘real’ Sinatra. There’s only what you see…. There’s nothing inside him. He puts out so terrifically that nothing can accumulate inside.”

The most ambitious attempt to parse all the traces of Sinatra has been James Kaplan’s biography, of which the second and concluding volume has just been published as Sinatra: The Chairman. The first installment, Frank: The Voice (2010), took Sinatra up to his Oscar-winning performance in From Here to Eternity: his reemergence from the low point marked by the plummeting of his record sales, the cancellation of his movie and television contracts, and the collapse of his brief marriage to Ava Gardner into very public turmoil.1

Advertisement

The first volume had an inherently dramatic three-part structure of brash irresistible ascent to pop stardom, precipitous fall from grace, and triumphant return to the heights from which he would never again be dislodged. The book did not shy from the most troubled and troubling sides of Sinatra’s professional and private lives, while strongly affirming his preeminence as—in Kaplan’s formulation—“the greatest interpretive musician of all time.”

Sinatra: The Chairman undertakes a more difficult task. With that 1954 return from near oblivion begins an era in which Sinatra’s doings multiply in every sphere so much that merely to keep a rough tally of them—recordings, movies, television shows, love affairs and liaisons, altercations and legal troubles, business enterprises and questionable connections and expanding political associations—becomes a challenge, before even getting to the deeper shape and significance of a life not only hyperactive almost beyond imagining but immeasurable in its ripple effects. To track all the splintered reflections of Sinatra you would have to comb through all the detritus of the twentieth century.

As a result Sinatra: The Chairman is more sprawling than its predecessor. Kaplan risks exhaustion as he turns over the life year by year, sometimes day by day and in some critical moments hour by hour. The exhaustion stems in part from gauging just how much relentless energy it took to sustain Sinatra’s activities in any given week, and grasping that for him there really was never any down time. The rhythm of work he maintained in the years following his comeback—laying down tracks with Nelson Riddle in such legendary collaborations as In the Wee Small Hours (1955), Songs for Swingin’ Lovers! (1956), and Only the Lonely (1958), demonstrating his great natural acting abilities in films like Suddenly (1954), The Man with the Golden Arm (1955), and Some Came Running (1958), taking his place as the ultimate headliner at the Sands in Las Vegas, the Fontainebleau in Miami, the Copa in New York—was more than matched by an offstage life in which sex, Jack Daniels, and boistrous all-night partying kept him from ever feeling fatally unoccupied. “So long as I keep busy, I feel great,” he told a reporter in 1956.

As Kaplan notes, “sleep, solitude, and leisure did not sit well with him.” (Sinatra’s valet George Jacobs remarked: “Today they’d give him Ritalin.”2) He would establish around himself a court of drinking buddies and hangers-on whose bound duty was to keep up with his whims and cravings until the first rays of sunlight (what Sinatra liked to call “Five O’Clock Vegas Blue”) penetrated the hotel suite. For those who couldn’t keep pace there might be penalties; when Peter and Pat Lawford declined to accompany him on a spur-of-the-moment trip to his house in Palm Springs, he went ahead on his own and proceeded to rip up the wardrobe of clothes they kept there, tossing them in the swimming pool for good measure.

Following Sinatra from one episode to the next, the search for progression—for signs of definitive mellowing or gathering tranquility, or simply of learning from experience—is repeatedly frustrated. In close proximity we find recording sessions of extraordinarily sensitive artistry and outbursts of uncontrolled rage, often directed at the most powerless; heartfelt charitable gestures and the apparently indifferent snubbing of old collaborators; incident following incident as if it were a matter of blind chance which aspect of him would show up at a particular moment.

With Sinatra, in Kaplan’s words,

the sublime and the ridiculous, the exquisite and the coarse, alternated so quickly and frequently that it’s useless to try to reconcile them. He wasn’t one thing or the other; he was both, and then a moment later he was something else again.

As a result he was feared even by his intimates, and not just because of the menacing aura of some of his associates. Few felt invulnerable to his mood swings. “There’s only one person in this world I’m afraid of,” said Nelson Riddle, who had worked with him so closely over so many years. “Not physically—but afraid of nonetheless. It’s Frank, because you can’t tell what he’s going to do. One minute he’ll be fine, but he can change very fast.” Time after time old friends would find themselves cast out of the fold, temporarily or forever, for having chosen the wrong moment to challenge his judgment.

There is the impression of a life in which everything remains in the present tense. There is no need for him to revisit the past because it inhabits him, including every haunting desire and every long-nurtured grudge. His chronic sleeplessness dissolves the border between one day and the next, and he seems to exist in a single charged-up moment endlessly extended. His force as an actor—on the occasions, increasingly rare, when he allowed that gift to show itself—has nothing to do with range or nuance. He had no training or taste for theatrical make-believe. What comes across, and dominates the screen, is an unmediated presence that reads as naked sincerity. (Elia Kazan, who had expressed skepticism about Sinatra as an actor, was taken to see him perform at the Fontainebleau and is said to have remarked: “This fuckin’ guy is the best actor I’ve ever seen in my life. He’s completely naked up there; I take back everything I said. He’s a genius.”) Otto Preminger’s The Man with the Golden Arm today seems one of Preminger’s lesser efforts, uncharacteristically stiff and cluttered, but Sinatra, as the battered-down junkie Frankie Machine, cuts through all the actorly mannerisms of the rest of the cast and brings the thing to life.

Advertisement

He convinces because of everything that he doesn’t do, the fully articulated assertions that he can’t quite get out, the expansive gestures he’s too weary to attempt, the unconcealed desire to evade the situation he’s trapped in. As in all those photographic portraits of Sinatra, it’s astonishing how much expressive power he can get out of just letting his face be there. On an album cover that same face, smiling broadly and decked by a fedora, might invite the whole world to the best party ever; in The Man with the Golden Arm it looks like a confession to some profound and ineradicable fear. The man who imposed himself as a new model of masculinity for the postwar generation—vulnerable yet cocky, as tough or as sensitive as the situation required—had a singular gift for showing himself unmanned by self-doubt and suspicion.

This is of course only in part a story about show business. The Voice’s solitary saga of Frankie ascendant becomes, in The Chairman, a collective drama of life among the powerful and the famous and the would-be famous, in which Sinatra finds himself at times an unwilling and unhappy onlooker, even a victim. The moment the Kennedys appear on the horizon of Sinatra’s life, with their promise of a direct connection to political power, unleashes events—Sinatra’s all-out efforts to get JFK (or, as he nicknamed him, “Chickie Baby”) elected president and the subsequent collapse of his hopes for an enduring link to the Kennedy presidency—that keep Kaplan busy for many hundreds of pages charting a tangled maze of male bonding, political maneuvering, sexual procurement, and the currying of underworld favors.

A thick aroma of rumor and surveillance, of secret cajolement and unspoken threat, filters into the hedonistic precincts of Sinatra’s domains in Las Vegas and Palm Springs. An FBI memo reports on “an alleged indiscreet party recently held at Palm Springs in which participants were said to be Senator John Kennedy, his brother-in-law Peter Lawford, the actor, and Frank Sinatra.” Walter Winchell speculates that Sinatra may be Kennedy’s pick for ambassador to Italy. At the outset of JFK’s presidential campaign Joseph P. Kennedy confides to Sinatra: “I think that you can help me in West Virginia and Illinois with our friends. You understand, Frank, I can’t go. They’re my friends, too, but I can’t approach them.”

The fact that no two participants quite agree on the details of anything said to have happened just makes it more mesmerizing, a theater of manipulative illusion in which it is often unclear whose strings are being pulled. By the time we get around to contemplating the ambiguous figure of Judith Campbell Exner, by turns the lover of Sinatra (who met her in the company of Angie Dickinson at Sinatra’s Beverly Hills restaurant Puccini), John F. Kennedy (to whom Sinatra introduced her), and Sam Giancana (who reportedly told her, “If it wasn’t for me, your boyfriend wouldn’t even be in the White House”)—while taking time out to consider the bonds between Sinatra and Marilyn Monroe, between Monroe and JFK and his brother Bobby, and between Giancana and the CIA, who were holding discussions at the Fontainebleau (at the same time that Sinatra was appearing there) about the possibility of the mob bumping off Fidel Castro—the narrative skitters into widening realms of wildness.

A reader who lived through this era can anticipate what is coming at each turn, yet still be overtaken by a sense of how anomalous it all is. Can these things really have happened like this? Sinatra begins to seem the most improbable of characters—someone who could only have existed through the rarest combination of utterly incompatible elements—and yet no more improbable than the age in which he was, in all senses of the term, so central a player.

All the varieties of power—political power, media power, star power, sexual power, mob power—jostle against each other in a scramble that from a distance could be mistaken for a party. The strangeness of that moment carries over into The Manchurian Candidate (1962), John Frankenheimer’s phantasmagoric farrago of brainwashing and political conspiracy, in which Sinatra provides an unforgettable portrait of a man becoming ruefully aware of his own extreme disorientation.

Some kind of high point for Sinatra was reached when he organized Kennedy’s inaugural gala, a three-hour stage spectacle featuring such disparate talents as Gene Kelly, Eleanor Roosevelt, Laurence Olivier, Ella Fitzgerald, Joey Bishop, Nat King Cole, and Leonard Bernstein—but not Sammy Davis, disinvited at the last minute at the insistence of the Kennedys, worried about the political repercussions of Davis’s interracial marriage. (Davis had already been vociferously booed, by the Mississippi delegation, when he made an appearance with Sinatra at the Democratic convention in July.) After a rocky start marred by rain delays, it turned into a splendid evening; even Jackie Kennedy, who mistrusted Sinatra’s influence on her husband, was apparently moved to tears by his rendition of “The House I Live In.”

For Sinatra the sweetest moment was hearing the new president pay tribute to him by name at the event:

I know we’re all indebted to a great friend—Frank Sinatra…. Long after he has ceased to sing, he is going to be standing up and speaking for the Democratic party, and I thank him on behalf of all of you tonight.

In the celebratory days that followed, he is described by a disenchanted houseguest as endlessly reliving the moment:

We all had to sit around Frank’s suite at the Sands and listen to that record of Kennedy thanking him. Frank would stand by the mantel and play it over and over, and we had to sit there for hours on end listening to every word.

The end for the Sinatra–Kennedy romance came when J. Edgar Hoover relayed wiretap evidence of the president’s involvement with Judith Campbell to Bobby Kennedy, who already had Sam Giancana in his sights. The upshot was Jack Kennedy’s abrupt cancellation of his scheduled March 1962 visit to Sinatra’s Palm Springs home—a visit for which Sinatra had invested in elaborate improvements, including a concrete helipad and a telephone hotline. In the event Kennedy stayed with Sinatra’s rival Bing Crosby, who was a longtime Republican. Sinatra’s disappointment was expressed in a destructive rampage, “smashing his precious collection of JFK photographs, kicking in the door of the presidential guest room, even trying to wrest the gold plaque from the door.”

This sort of behavior was fairly standard with Sinatra, who had reacted similarly after losing the lead role in On the Waterfront to Marlon Brando and after being forced by intense political pressure to fire the blacklisted screenwriter Albert Maltz, whom he had hired in 1960 for an intended film version of William Bradford Huie’s The Execution of Private Slovik. When he came up against the limits of his power, the obliteration of furnishings always seemed to be in order.

The Kennedy humiliation was on another level than those earlier setbacks. He had staked his own self-image on his partnership with Kennedy, and his ultimate reaction, in Kaplan’s phrase, was that of “a spurned lover”:

If he would only pick up the telephone and call me and say that it was politically difficult to have me around, I would understand…. But he has never called me.

He never publicly criticized Kennedy, but his political loyalties—like his parents he was a lifelong Democrat, unequivocally liberal in his early years of stardom—would migrate over time to the Republicans. He would form a friendship with Spiro Agnew and ultimately be a welcome guest in the Reagan White House.

The break with Kennedy takes us only to the midpoint of Kaplan’s book, and although Sinatra was just forty-six, this is the time when his early upward aspiration appears to give way to a determined persistence, even when the goal is far from clear. (That persistence would finally bring him back from an early retirement into further decades of touring, singing the old songs until he couldn’t remember the lyrics anymore.)

With Kennedy he had hoped to break through into a new sphere of power and influence, to become undeniably a part of the culture’s highest elite. In the end he had been rejected once more as not quite fit for that realm. There was nothing new in that. A Time cover story of 1955, when Sinatra was at a moment of triumphant accomplishment as a musician and actor, gives him an arm’s-length treatment steeped in innuendo:

With charm and sharp edges and a snake-slick gift of song, he has dazzled and slashed and coiled his way through a career unparalleled in extravagance by any other entertainer of his generation.

The figure of the serpentine Italian charmer with the implied hidden blade would always lurk somewhere behind Sinatra’s public image. Kaplan recounts that years later, in his mid-fifties, when he made an impromptu marriage proposal to Louis B. Mayer’s daughter Edie Goetz, a longtime friend he had been courting since her husband’s death, she recoiled with the words: “Why, Frank, I couldn’t marry you…Why…why…you’re nothing but a hoodlum.” Not all the sudden freeze-outs in Sinatra’s life came from him.

The years after the Kennedy debacle were marked by further uproar and other kinds of trouble: his difficulties with the Nevada Gaming Control Board, which led to his forced surrender of his gaming license; the kidnapping of his son Frank Sinatra Jr. by a handful of fantastically inept schemers; his unlikely and short-lived marriage to Mia Farrow; his violent headline-getting set-tos with new management at the Sands and later at Caesars Palace. Each of these is an extravagant story in itself and Kaplan takes due care to sift through the available and as usual contradictory evidence to catch the nuances of each opposing viewpoint.

So tumultuous is the account of Sinatra’s days and nights in this period that one must draw back to remember that at the same time all this was going on he was continuing to make great records, entering on a fruitful collaboration with Count Basie and Quincy Jones, laying down gorgeous tracks with Antonio Carlos Jobim, and releasing a series of late-career hits that for a moment made him competitive with the Beatles: “It Was a Very Good Year,” “That’s Life,” “My Way,” and (a song he hated though it was the biggest hit of them all) “Strangers in the Night.”

This late resurgence in the pop charts ought to have been sweet revenge. His dislike of rock and roll was so intense that he had forbidden his record label Reprise (founded in 1960, sold to Warners in 1963) to sign any rock artists. Kaplan offers a cameo of Sinatra smashing in his car radio in 1967 after hearing the Doors’ “Light My Fire” being played on three stations in a row.

Part of the pleasure of Kaplan’s book is in the many voices that he allows to speak, that shifting chorus of friends, lovers, enemies, investigators, and fanatical admirers who have all felt the need to get some handle on what Sinatra was about. Then there is Sinatra himself. He was cagy about expressing himself—when Playboy asked for an interview, he farmed the whole thing out, questions and answers alike, to a freelance writer named Mike Shore, who did such a good job that it has been quoted ever since as the lowdown on Frank’s view of things.

Yet when Sinatra did undertake to state a credo, it was remarkably unvarying even under the most varied circumstances. During a 1954 nightclub brawl with a press agent, he shouted: “I have talent and I am dependent only on myself.” In 1963, while being questioned by a Nevada official about his friendship with Sam Giancana, he declared: “This is a way of life, and a man has to lead his own life.” A line he speaks in the 1966 film Assault on a Queen, whose script is credited to Rod Serling, sounds as if taken from the same promptbook: “I just live my life as I see fit. I do what I want and I have a ball. I take things as they come.” Onscreen, in a film otherwise undistinguished in every way, he gives the words credibility by the weary yet relaxed indifference with which he utters them, as if to say, “That’s my line-reading—you want to make something out of it?”

I can remember listening when I was seventeen to Sinatra singing “When I was seventeen…” (in “It Was a Very Good Year”) and finding him a comfortably sturdy presence: not at that point for any perceived tenderness or intellectual sympathy or aesthetic daring, but simply for having gone through life apparently without compromise, and having thereby earned respect even for those wretched late-career movie vehicles in which he didn’t do much more than show up. There was a lot we didn’t know then, and as Kaplan makes clear there is much more that surely will never be known about a life lived in so intense and crowded a fashion. This lover of Puccini made a kind of gaudy opera of his life, so that every time he sings a song he is in character, enacting one scene or another of a single great drama.

It is true, as David Lehman notes, that these days Sinatra figures constantly as background music:

You will hear him in commercials for vodka or sour mash whiskey, as segue music on radio and television, as the background music in the restaurant with steak and chops on the menu and a full bar, as the music in your head, as the song playing over the movie’s opening credits…or closing credits.

But it is hard to imagine him fading into the background. He continues to insist on being there, a prodigious eruption of the life force always touched with the outrageous. Then again, as his daughter Tina has noted: “Had he been a healthier, less tortured man, he might have been Perry Como.”

-

1

I reviewed Kaplan’s first volume in “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man,” The New York Review, February 10, 2011. ↩

-

2

George Jacobs and William Stadiem, Mr. S: My Life with Frank Sinatra (HarperEntertainment, 2003), p. 75. Jacobs’s memoir, which is quoted extensively by Kaplan, is one of the most convincing close-up portraits of Sinatra. ↩