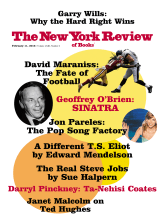

A pleasure, an annoyance, a digital marvel, a mass-market commodity, a cultural touchstone, a gimmicky cheap shot—a twenty-first-century pop hit can be all of those, often at the same time. Even for those who try to tune them out, the songs insinuate themselves. They pour out of radios, pulse loudly at stores, back up TV commercials, punctuate movies, provide walk-up music for sports stars, pump through exercise classes, leak from the earbuds of nearby subway riders. They are relentlessly and almost scientifically catchy. The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory by John Seabrook, a staff writer at The New Yorker, describes how they get that way.

For listeners whose tastes were shaped by the pop hits of earlier eras, with their hand-played instruments and naturalistic voices, the modern Top 10 sound especially artificial, almost post-human. The songs are full of synthetic sounds and unvarying programmed drumbeats, while voices—which are sometimes the last physical, human element—arrive with computer-tuned precision and a robotic buzz. The songs are constructed with software and played back through digital processors. Even as they aim for the visceral, real-world response of a dance or a sing-along, they sound almost entirely virtual, echoing in cyberspace. They are music for the current and next generations of digital natives.

In The Song Machine, Seabrook pulls together both how and why the craft of hit-making has revved up to Internet speed. In alert close-up reporting, with financial savvy and historical perspective, he explains how Top 10 songwriting has become industrialized—separated into component tasks that are assigned to specialists.

Top 10 pop, a peculiar subspecies of music shaped by the demands of radio, has sidelined the old, romantic songwriting archetypes of the lone troubadour with a guitar—like Bob Dylan or Joni Mitchell—and of the self-contained band, like the Rolling Stones or U2. Now, a newer kind of collaboration prevails: more atomized, more ephemeral. The songwriter and producer Dr. Luke (aka Lukasz Gottwald, the longtime guitarist in the Saturday Night Live band who went on to make hits with Miley Cyrus and Katy Perry) itemizes his workforce to Seabrook as “artists, producers, topliners, beat makers, melody people, vibe people, and just lyric people.” The book makes clear what all those jobs are, as Seabrook visits studios to observe hitmakers at work.

Pop music has always been a balancing act of art and commerce, and in the twenty-first century there are different thumbs on the scale. To become a Top 10 hit now, a song has to compete against an infinitude of rival possibilities for the ever more fragmented attention of its potential audience. It can’t waste a millisecond in getting attention, and its commercial performance is measured more precisely than ever. (The streaming service Spotify, gathering data from every click, tabulates not only a user’s entire listening history, but exactly how much of each song was played.) At the same time, a successful song has to do what pop hits have always done: create the musical and emotional connection that makes a listener want to hear it again and again.

It might seem that since today’s hits are made, played, and tallied with machines, they are also created by automation. Surely some machine, somewhere, must hold an algorithm that may register as ingenious or infernal but can guarantee that a song will be a hit: a musical analogue, as Seabrook suggests, to snack food’s addictive, experimentally ascertained “bliss point” of salt, sweetness, fat, and crunch.

But the beauty of popular music is that it can never be quite that simple. Hit songs, for all their formulas and established production methods, are not the kind of consumer product that can be standardized and then endlessly replicated. Far from it: each hit needs some distinguishing novelty, every time, hit after hit. It has to balance familiarity and surprise.

Songs also depend on human beings as writers, performers, and listeners, and humans are marvelously inconstant; today’s thrill is next year’s yawn. Throughout pop history, styles and sounds have followed a cycle from innovation to bandwagon trend to banality—and perhaps, many years later, to a nostalgic revival. Careers and cultural personas are built through repeated exposure and the gradual revelation of a performer’s range and ambitions. But there’s little loyalty in the Top 10, and no guarantee that one hit leads to another.

The Song Machine joins a strong tradition of hard-headed music-business reporting by music lovers: books like Fred Goodman’s The Mansion on the Hill, on how 1960s and 1970s rock turned professional; Nelson George’s Where Did Our Love Go, the inside story of Motown Records; and Dan Charnas’s history of hip-hop, The Big Payback. Seabrook’s book is populated by this generation’s versions of archetypal music-business characters: celebrities gone wild like Britney Spears, belters with star quality like Rihanna and Kelly Clarkson, know-it-all media executives, money-mad hustlers, naive but gifted talents, and the not-so-naive producers and songwriters who work constantly in the background because they love the process and profits of making hits. Shrewdly, Seabrook keeps as careful an eye on the background figures as on the stars.

Advertisement

Briskly but thoroughly, he summarizes multiple forces that converge in contemporary pop. He includes primers on the ever-advancing technology of synthetic sounds and digital recording, on how the consolidation of radio station ownership led to the homogenization of “hit radio” playlists, on royalty structures and billion-dollar business deals.

The book’s persistent backdrop is the deep anxiety of musicians and the owners of record labels over the financially perilous and still-unresolved transition to digital music. Recording companies now bring in roughly half the revenue they did at their peak in 1999, when their business revolved around selling profitable albums as CDs through manufacturing and distribution they largely controlled. Since then, distribution has migrated online and out of control, while the album has been unbundled and all but vaporized.

The iTunes Store allows users to buy any individual song instead of a whole album, and now streaming subscription services like Spotify and Apple Music sell an entire month of access to music for what had been the price of just one CD. (Seabrook has made his own playlists of songs discussed in the book available on his website and on Spotify.) Listeners can also simply watch a song’s video for free on YouTube.

The struggling major labels have learned that they are sustained primarily by a handful of huge hits. The “long tail” envisioned by digital idealists—in which access provided by the Internet was going to bring larger audiences to back catalogs, deserving midlevel acts, and newly discoverable local music from any place in the world—may have broadened listening habits. But the blockbusters still generate the profits. With shrunken budgets and relentlessly precise metrics, record companies are increasingly desperate for sure things.

So are radio programmers, who are still crucial gatekeepers to mass success. They have found that an average listener gives a song only seven seconds before deciding whether to change the station. Music, as digital information, can itself be analyzed by computer, and research services hired by radio stations claim they can predict whether a song will be a hit based on its similarity to previous hits. (Of course, if radio stations only play what they are told will be hits, the prediction becomes self-fulfilling.)

All that pressure has created an unexpected outcome: a dependence on a surprisingly small number of proven producers and songwriters who churn out material for all sorts of Top 10 contenders, dominating the pop charts. In the pop version of income inequality, perpetuating the gulf between haves and have-nots, the most successful performers get first dibs on the hottest producers and songwriters of the moment. Yet while singers come and go, an oligarchy of producers endures.

As Seabrook explains, the hit factory is not a new idea. It’s a long-standing music-business dream that has now been refined, globalized, and digitized. The archetypal hit factory, Motown Records, modeled itself on the assembly lines of its Detroit hometown, striving to manufacture songs, stars, and careers under one roof in its Hitsville U.S.A. headquarters. Seabrook also notes other antecedents: the Brill Building and Don Kirshner’s Aldon Music in New York City and Phil Spector’s Philles Records in Los Angeles, which were factories for girl-group hits and other fondly remembered 1960s pop. Each organization harnessed in-house teams of songwriters and performers, attempting to systematize hit-making.

Those early hit factories—with teams like Gerry Goffin and Carole King at Aldon or Brian Holland, Lamont Dozier, and Eddie Holland at Motown—had a reign on the Top 40 that gave baby boomers a generational songbook. They made songs that sounded as if they came straight from the heart, even though that heart was plurally constructed: songs like “Be My Baby,” “Will You Love Me Tomorrow,” “We Gotta Get Out of This Place,” and “You Keep Me Hangin’ On.”

Yet each of those song factories had a heyday lasting less than a decade before their success gave way to changing tastes, clashing personalities, artistic ambitions, and business disputes (usually over exploitative contracts, still a music-business staple). But one hit factory and its later iterations have outlasted them all, landing songs in the Top 10 for two decades and counting. That would be the atelier surrounding the shadowy but ubiquitous hero of The Song Machine: the songwriter and producer Max Martin.

Martin, a self-effacing Swedish musician, is, by the numbers, the most popular songwriter of the twenty-first century. He trails only John Lennon and Paul McCartney as the songwriter with the most number-one hits; his total hits already outnumber those of the Beatles and Michael Jackson. But unlike Jackson or the Beatles, Martin is more a craftsman than a celebrity. He stays in the background, and what he has to say is entirely in his tunes and his productions. Other people write the lyrics, while singers carry the songs into the spotlight, using Martin’s tunes to project their own personas.

Advertisement

Martin’s winning strategy is that he regularly rejuvenates his sound by finding collaborators who can rough up his pretty melodies. His tenure as a chartbusting songwriter has been remarkably protracted: from the Backstreet Boys and Britney Spears in the 1990s to Taylor Swift, the Weeknd, and Adele right now. He is the consummate example of the digital, industrialized songwriter, at the center of a constantly reconfigured assortment of collaborators.

In the Internet era, songwriters and performers may not be in the same building or on the same continent; they may never have met. Songs in progress flit from one recording studio—or simply one laptop computer—to another. Current songwriters and producers often use a method Seabrook calls “track-and-hook,” in which beat-makers and producers supply the rhythmic and harmonic foundation of a song: the track. Then come the topliners, the vocalist-songwriters who fill in the blank spaces with melodies and the outlines of lyrics: “top lines.” They work fast and instinctively, arranging for a visceral mesh of melody, rhythm, and verbal fragments that listeners can grasp just as immediately—a skill at once primal and rare. Once the song is written, the “artist” selects it, sings it, and sells it to the world.

Potential hits may also be assembled in high-pressure pop think tanks called “writer camps,” where a deep-pocketed star—Beyoncé, perhaps—convenes dozens of producers, composers, and lyricists in hotels and studios, where they run through every permutation of producers and topliners. The campers are often a mix of longtime pros and newcomers from the hipper fringes, sharing their innovations or eccentricities for the chance at a pop payoff. “Camp counselors” schedule teams to come up with a song before lunch, then reshuffle the teams to come up with another afterward, with daily playbacks to keep everyone competitive. “If the artist happens to be present,” Seabrook writes, “the artist circulates among the different sessions, throwing out concepts, checking on the works in progress, picking up musical pollen in one session and shedding it on others.”

In a different, less physically proximate kind of songwriting contest, one very simple track—a single beat or a chord progression—gets sent simultaneously to dozens of potential collaborators. Then the producer and singer might choose a verse from one response, a chorus from another, an instrumental hook from yet another: digital brainstorming. Many of the songwriter-producers in the book are blunt about describing their work more as a business than a form of self-expression—though that may be more a matter of our era’s MBA mentality, combined with a hip-hop culture of competitive striving gone mainstream. The Beatles wanted hits, too.

Committee efforts can homogenize songs, removing artisanal innovations in a search for the most generalized content—the age-old complaint about mass entertainment. As Seabrook notes, track-and-hook songwriting is more like the process of creating a film or a television show than the old troubadour model. Yet the virtue of many pop songs is exactly in their universality. They can ennoble a widely shared experience, finding the soul behind the cliché. Multiple authorship can also pluralize the perspective of a song, offering more listeners more ways to connect.

Consider “Bad Blood,” a number-one summer hit in 2015 for Taylor Swift, which was also named MTV’s Video of the Year. It is a mini-blockbuster of a video filled with celebrity cameos and action-movie stunts. The hit-single version that appeared as a single has four songwriters, and was substantially reworked from the “Bad Blood” that appeared on Swift’s 2014 album 1989; hit-makers are anything but lazy. The single added the rapper Kendrick Lamar (who performs his own verses in the song) to the original team of Swift, Max Martin, and one of Martin’s latest collaborators, the Swedish musician and producer Shellback.

“Bad Blood” is targeted broadly. It’s a pop complaint about betrayal, underlining its blunt confrontation with a jarringly imperfect rhyme: “Now we got bad blood/You know it used to be mad love.” Swift’s lead vocals grow brightly indignant on the way to that terse chorus, which uses the same musical phrase for both lines: repetition enforcing catchiness. The song is also an arena-scale anthem, particularly when its cathedral-sized keyboard tones appear. And while Swift was classified as a country act before she took her place as a pop titan, “Bad Blood” has an unmistakable hip-hop core, both from its programmed beat and from the prominent presence of Lamar, one of the most widely acclaimed and ambitious rappers of the moment.

“Bad Blood” is forceful and repetitive with intricate underpinnings, the kind of song that Seabrook describes as “industrial-strength products, made for malls, stadiums, airports, casinos, gyms, and the Super Bowl half-time show.” It’s an interracial, machine-tooled, recombinant hybrid, drawing its mass audience from every potential market it can. It’s as slickly calculated as a product can be.

Yet to many of its millions of listeners, it’s also just how they feel, and something they can share. Seabrook is so engrossed in the music-making behind the hits that he sometimes takes lyrics for granted, but they are more than melodic placeholders; they are, at best, distillates of something listeners wanted to say themselves. And no matter how the song was constructed, a hit needs a human voice and face: the pop star who can put across the whole fabrication as a believable personal statement, a product of flesh and breath.

Max Martin’s song factory started, improbably enough, in Stockholm. Its remoteness from pop’s capital cities turned out to be an advantage; Stockholm’s songwriters had no personal or regional allegiances, only a fascination with how hits are constructed. Martin and his group are geographic and cultural outsiders gazing from a distance, simultaneously analytic and enamored. Seabrook writes that for Martin and his largely Swedish collaborators, “their foreign-ness to English and American music allows them to inhabit, and in certain ways co-opt, different genres—R&B, rock, hip-hop—and convert them to mainstream pop.”

The founding Stockholm visionary was Denniz PoP, a DJ-turned-producer-turned-songwriter who parlayed his club experience—nightly tests of immediate response to music—into a talent for simplifying and clarifying arrangements. PoP, who died of cancer in 1998 as his methods were about to spread worldwide, didn’t play instruments or sing. But he knew what he and his dance-floor crowds wanted: solid beats and big choruses. At his burgeoning hit factory, Cheiron Records, he gathered fellow Swedish pop-makers who were happy to specialize and collaborate. But PoP also had a motto for the more unruly, unsystematic aspects of songwriting. Sometimes, he would say, you have to “let art win.”

Max Martin, PoP’s most brilliant disciple, was born Martin Karl Sandberg in Stockholm in 1971. He was the trained musician that PoP was not. He studied music theory and notation as well as French horn, keyboards, and drums, until he dropped out of high school in the early 1990s to sing in a glam-rock band named It’s Alive. Denniz PoP signed It’s Alive to Cheiron Records, and when the band’s album flopped, PoP recruited Sandberg for studio work. (He also, without prior notice, came up with the Max Martin pseudonym; Martin first saw it as a production credit on a disc.) Sandberg/Martin could notate arrangements for studio musicians; he was also, as he would go on to prove year after year, a consistently successful creator of memorable tunes.

Martin has both the traditional pop songwriter’s gift for melody and a talent for what he calls “melodic math.” Seabrook explains melodic math rather sketchily: “In addition to working rhythmically, the sound of the words had to fit with the melody”—a description that could just as easily apply to Cole Porter and Paul Simon. But Seabrook also interviews one of Martin’s lyricists, Bonnie McKee, who gets more specific: “The syllables in the first part of the chorus have to repeat in the second part,” she explains. “If you add a syllable, or take it away, it’s a completely different melody to him.” There is, indeed, a subliminally reassuring element of symmetry in songs that Martin has a hand in, from Britney Spears’s “Oops!…I Did It Again” to Kelly Clarkson’s “Since U Been Gone” to Taylor Swift’s “Blank Space.”

As a producer, Martin has a meticulous sense of structure and drama, of how to lift a song from verse through pre-chorus through triumphal chorus. There is also a special quality of transparency to his productions; each note from each instrument is neatly defined and immediately legible, even through tiny earbuds. He is also known as a master of “comping”: the tedious detail work of editing that arrives at an optimal lead vocal from countless takes, syllable by syllable if necessary.

Along with his ear and his diligence, Martin has an entrepreneur’s skill at team-building and product updates. Unlike his hit-factory predecessors, he has not attached himself to the kind of trademark sound or production approach—as did the songwriter and producer Phil Spector—that the pop market regularly embraces and discards. When synth-pop wears out its welcome, he latches onto a guitarist for an infusion of rock (Dr. Luke was one of them). When hip-hop is ascendant, his productions deploy the crispest drum samples while he summons top rappers for guest appearances. Martin’s collaborators can change with pop fashion, while his tunes are supremely portable across styles.

But while Martin appears as a gifted, rational technocrat—from a certain remove, since Seabrook couldn’t interview him—all around him is pop’s age-old hurly-burly. On- and offstage, Seabrook finds a music business filled with “demon-driven strivers” with tangled backstories, drawing on their talent, greed, intuition, conniving, luck, and, at times, creativity.

The true stories are outlandish. Martin’s song factory built careers for the Backstreet Boys and N’Sync—boy bands who were bilked by a manager who is now jailed for running a nine-figure Ponzi scheme—and for Britney Spears, who went from Disney Mouseketeer to teenage tease to sex symbol to tabloid headline to Las Vegas attraction.

Together or separately, Martin and his protégé Dr. Luke have supplied songs for belters like Rihanna and Kelly Clarkson. Rihanna gives Seabrook the story of someone who grew up amid domestic abuse and made herself the image of allure and power. The chapter on Clarkson, the first winner of the reality show American Idol, explores the machinations of television producers and the clash of executive and artistic egos. Another of the book’s strivers is the 2015 Super Bowl halftime show star, Katy Perry. She’s the daughter of Pentecostal pastors and started out singing Christian pop; now she makes video clips like the one for “California Gurls,” which peaks with her shooting whipped cream from her brassiere. These are pop professionals caught up in show business, yet through all the packaging and contrivance, listeners detect—or are able to project—something genuine.

Seabrook’s clear favorite among the many characters in The Song Machine is a topliner named Ester Dean, who has been the melodic id, and often libido, behind hits for Rihanna, Beyoncé, and Katy Perry. Seabrook describes how her ambitions for her own career as a singer have been hampered by her usefulness as a collaborator; when she comes up with something that feels like a hit, producers would rather place the song with an established star.

Seabrook presents Dean as a creature running entirely on instinct. She has no musical training but did plenty of singing in church; she has a gutsy voice and an ear for detail. On her cell phone, she keeps lists of phrases that could be seeds of songs. And she has the exact skill needed for a songwriting universe of track-and-hook; Seabrook calls her “a hook-spitting savant.” Producers play tracks for her; she responds aloud. She explains, “I just go into the booth and I scream and I sing and I yell, and sometimes it’s words but most time it’s not.” Lyrics will be devised to fit her melody, which already fits the beat. Dean’s impulse of the moment will, with polishing, promotion, and luck, bring instant gratification to a mass audience.

Is this what songwriting has come to, this primal yawp into a high-tech matrix? Well, often, yes. And there is astonishing technical firepower now available to producers and songwriters: seismic dance beats, instrumental sounds never heard before, pitch correction for imprecise singers. Digital recording can reproduce and tweak any existing musical work. And since much of music-making has migrated to the virtual realm, with all its speed and flexibility, the creation of a song can seem far removed from the organic, physical musicality of past eras. Yet in that respect, pop is of a piece with twenty-first century movies, television shows, and video games, all flaunting their digital pizzazz.

And beyond the changes in tools and methods, beyond the shifting sonic vocabulary, this is how songs have always been made. A piano was once a high-tech instrument. A drummer’s beat was once a rhythm track. Songwriters were shouting nonsense syllables, hoping to glean a melody or a lyric, long before computers were making music. A song still has to be plucked instinctively from the ether, summoned by an emotion or idea, improvised and then shaped into a pop structure. A pop hit, in its fearsomely competitive milieu, still has to provide pleasure and connection, the sense that the glamorous voice in the earphones is singing the listener’s heart out. It can never be just a machine. Somewhere amid all the digital wonderment and business frenzy, in the best pop songs art still wins.