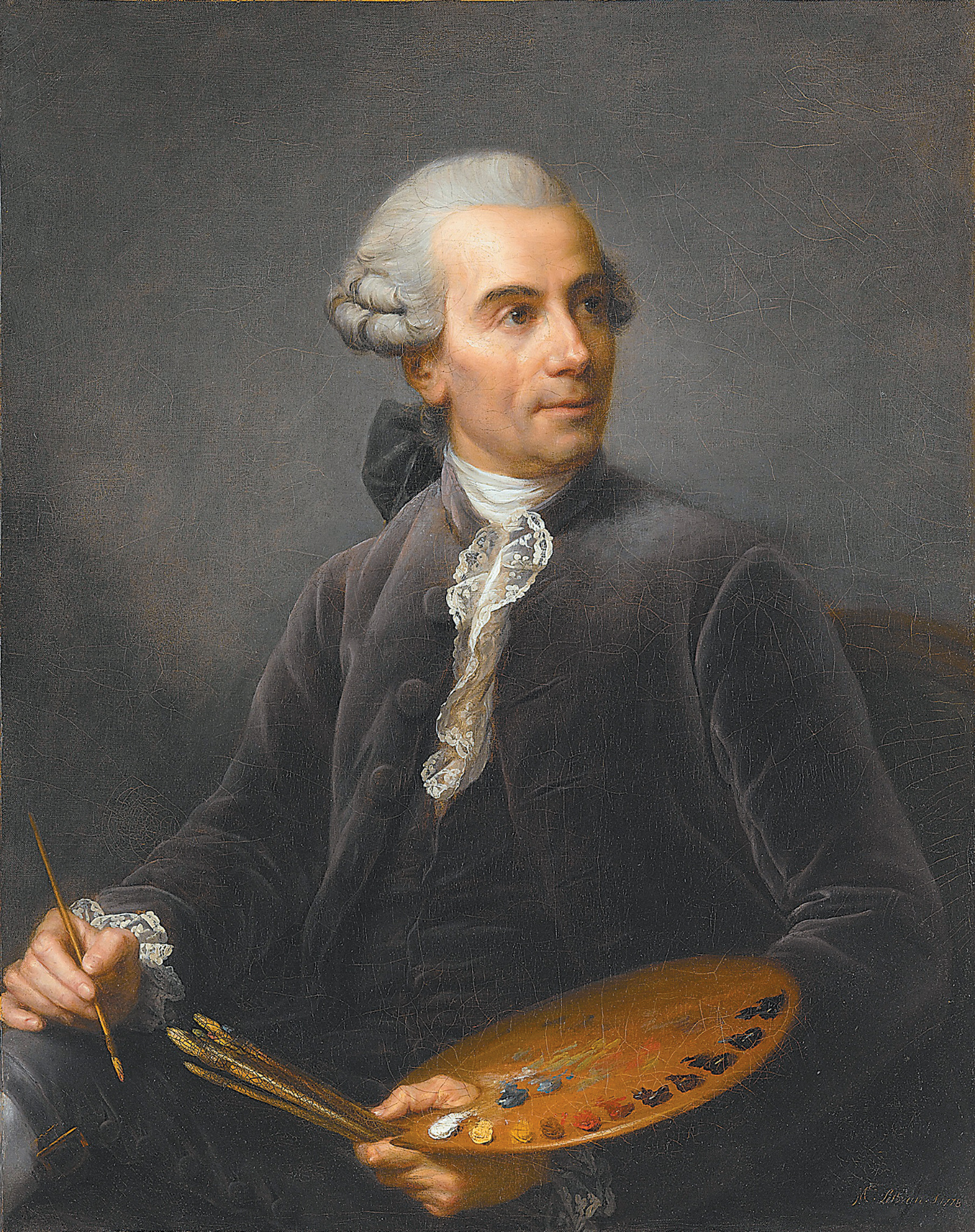

It comes as something of a surprise that we have had to wait until 2015 for a comprehensive exhibition in France of the work of Madame Vigée Le Brun—perhaps the most gifted French portraitist of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, an artist who gave posterity the most enduring image of Queen Marie Antoinette. The only comparable show of her work prior to this one was mounted more than thirty years ago at the Kimbell Art Museum, in Fort Worth, through the instigation of the art historian Joseph Baillio. The Paris show, somewhat scaled down, is now on view at New York’s Metropolitan Museum. What is the reason for this lack of interest in the artist’s homeland?

The quality of her work has never been called into question, though there can be no denying a certain tradition of mistrust toward female painters. The unbreakable bond with Marie Antoinette certainly did nothing to help her reputation in Republican France. Vigée Le Brun is known first and foremost as the queen’s portraitist and she remained attached to the values of the ancien régime. Her work celebrates the most engaging qualities of the Enlightenment: a natural elegance and a new attitude, strongly influenced by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, toward motherly love. What’s more, over the course of a very long career—she died in 1842 at the age of eighty-six, having executed more than 660 portraits—she never really evolved much. As Richard Dorment pointed out in these pages twenty-five years ago:

Her only miscalculation, had she cared for her posthumous reputation, was her own consistency: she continued to paint beautifully wrought portraits of all the most prominent people with flair and conviction long after the Revolution and its aftermath had rendered such confidence obsolete. Her paintings suggest a robust optimism when it was the doubt and self-questioning of romantic portraiture that would appeal to the twentieth-century imagination.1

Paradoxically, she’s never been forgotten. The memoirs that she wrote at the end of her life have been unfailingly republished.2 Numerous biographies have appeared both in French and in English. The earliest dates from 1890, just fifty years after her death; the latest from 2011. The author of the most recent study, Geneviève Haroche-Bouzinac, has done a painstakingly thorough job, but Joseph Baillio’s 1982 monograph remains irreplaceable because of its author’s long-standing familiarity with his subject.3 The essays by Joseph Baillio, Katharine Baetjer, and Paul Lang published in the exhibition catalog are indispensable for anyone seeking to understand the complexity of the painter’s life and work.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée was born on April 16, 1755. Her father was a painter who worked in pastels; her mother was a hairstylist, a profession that, in an era of quasi-architectural coiffures, demanded uncommon taste and skill. Their young daughter soon displayed a great facility in drawing. Her father encouraged her to use his pastel sticks, gave her her first lessons, and predicted that she’d have a future as a painter. But he died too young, choking to death on a fishbone. His daughter was twelve. In her grief, she set aside her pastels and lost her high spirits. Her mother’s second marriage, to a commercial goldsmith, François Le Sèvre, whom Louise detested from the start, did nothing to help matters.

Meanwhile, her mother urged her to study painting seriously. She started by copying drawings and busts in the atelier of the painter Gabriel Briard. Joseph Vernet, an old friend of her father’s, advised her not to adhere to any particular school but instead to look at and copy the work of the great masters. The remarkable thing is that she was therefore self-taught, trusting to her eyes, and began to paint professionally when she was just fifteen.

At first she painted the people around her, her family, her friends, and then the bourgeois residents of her neighborhood, which stood in the shadow of the Palais-Royal, the home of the Duc d’Orléans, cousin to the king. The duc’s daughter-in-law, the Duchesse de Chartres, heard from various tradesmen about the girl’s precocious talent (Paris was still basically a collection of villages). Her curiosity piqued, she asked her to paint her portrait. The portrait has since been lost but it met with complete satisfaction and served to throw open the doors of high society to the young artist. She soon began to earn money but her stepfather pocketed all her fees. She so resented the practice that she thought of marrying in order to escape his guardianship. It turned out that a marriageable bachelor was close at hand.

Le Sèvre had moved the family to an apartment in a grand town house that belonged to an art dealer named Jean-Baptiste Pierre Le Brun, grandnephew of Charles Le Brun, the court painter of Louis XIV. Jean-Baptiste occupied the second floor, the one with the highest ceilings and most elegant rooms, and filled the suite with important canvases. Le Brun bought and sold valuable collections. He was impressively knowledgeable about art and was himself a very good painter. He immediately realized that his young neighbor was remarkably talented and he gladly offered to lend her paintings to copy at her leisure. What’s more, the elegant young man, a smooth talker, made a good impression on the girl’s mother. He made plain his intentions, asking for and receiving her hand in marriage. The wedding took place in 1775, the year she turned twenty. She insisted on keeping her father’s surname, Vigée; a name by which she was already well known. From then on, she’d sign her work Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun.

Advertisement

The marriage was not to be a happy one with respect to their personal intimacy (in fact, she never painted Le Brun’s portrait, and the one that appears in the show is actually a self-portrait), but it did give her a daughter who for many years made her happy. Besides, Le Brun proved very useful to her and offered sound advice.

First of all, she accompanied him on his travels, which gave her an opportunity to complete her education. Her response to the work of Rubens, for instance, which she saw on a trip to the Netherlands, is that of the experienced technician that she had become. She closely observed the way the Flemish artist treated the gradations of light over the face; it was very much as a painter that she admired Le Chapeau de Paille, a portrait of Rubens’s sister-in-law, Susanna Fourment. She was charmed by the use of the hat as an accessory, and she adopted it in many of her own paintings, once even of the queen herself. Upon her return to Paris, she began working at a feverish pace, with her husband’s unreserved encouragement. He would henceforth manage with unnerving intuition the financial side of her career.

The trick was to set a price that wouldn’t scare off clients but place her above the competition. He never backed down. The price varied according to whether the client desired a bust without hands, with one hand, two hands, and with or without accessories. Prodigious worker that she would remain for the rest of her life, she finished forty portraits during her first year of marriage.

In 1778, her career, and the very course of her existence, were altered by a spectacular new commission: a portrait of the queen intended as a gift to her mother, the empress of Austria. She had already painted a portrait of the king’s brother, so she was not unknown to the royal family, but she was very young and lacked the official sanction of membership in the Académie. How then can we explain this surprising choice as anything but the determination of Marie Antoinette herself?

Marie Antoinette was exasperated by the artists for whom she had posed. “The painters kill me and cause me to despair…I’ve just received my portrait. It is such a poor likeness that I can’t send it,” she writes to her mother.4 In fact, though, it may simply have been too good a likeness. In any case, she decided to turn to Vigée Le Brun. She could only congratulate herself on the choice.

Vigée Le Brun certainly knew that getting the queen to pose was no easy matter. Subject to a thousand distractions, she had difficulty concentrating longer than a quarter of an hour. She was easily bored and if anything irritated her, her features tensed. The portraitist was sufficiently experienced to know that she’d have to work quickly if she wanted to avoid getting on her model’s nerves. As she wrote in her Conseils pour faire un Portrait:

This is how it works with women; you must flatter them, tell them how pretty they are, that they have fresh complexions, and so on and so forth…. That will put them in a good mood…. You must also tell them how well they pose; that encourages them to behave themselves.5

She also knew that it was in her interest to downplay the queen’s slightly protruding Habsburg jaw and bulging eyes, and to conceal the double chin that was just starting to emerge. After all, though the queen had a dazzling complexion, she was not pretty.

She pulled it off beautifully. Marie Antoinette was delighted with that first portrait. Vigée Le Brun was paid six thousand livres, three times as much as Gautier-Dagoty, an artist the royal family had previously employed.6 This was a very substantial sum when a household servant might earn fifty livres a year and a carriage cost two thousand.

Advertisement

The queen was so pleased that she commissioned Vigée Le Brun to do three more portraits, and in a clear sign of favor, arranged for her to be inducted into the Académie, which had previously rejected her, not because of her gender—there were four seats reserved for women—but on account of her marriage to an art dealer. The regulations of the Académie prohibited all connections between an artist and the art business. The art historian Pierre Rosenberg points out, in addition, that aside from Vernet, she didn’t get along with her fellow artists. The queen’s striking support particularly annoyed Jean-Baptiste Pierre, the king’s first painter and the director of the Académie.7

Vigée Le Brun thus became Marie Antoinette’s official painter and gradually grew to be responsible for the queen’s image. While the first portrait of the young queen—slightly haughty, in full court regalia, with the crown in plain sight on a nearby table, and a bust of Louis XVI atop a pedestal adorned by the figure of Justice looming over all—was very classic and even a bit stilted, the ones that followed would be more natural.

In fact, so natural that one of them, Marie Antoinette in a Chemise Dress (1783), caused a scandal. That the queen should choose to have herself painted in a white dress, à l’anglaise, without ornaments, wearing a straw hat, and a half-smile on her lips, came as a shock to the French public, who viewed this choice of apparel as a refusal to symbolize royalty, a contempt for traditional morality, and a blameworthy fondness for foreign fashion. The artist was forced to withdraw the portrait from the Salon and replace it with a canvas that had an identical pose but in which the unseemly dress à l’anglaise was replaced by a silk dress à la française, and the informal hat replaced by an elaborate coiffure. Here the natural ways the queen had introduced at the Trianon bowed to Versailles, where proper etiquette was regaining the upper hand, but the damage had been done and public opinion was rumbling: Vigée Le Brun had portrayed the queen in a carefree mood that failed to live up to the image expected of the king’s spouse.

In a recent book of a hundred or so pages that are as brilliant as they are original, the historian Marc Fumaroli gives a double portrait of queen and artist that clearly shows the slippage of women’s standing during that period. Previously, it had been understood that women had a significant influence on life in a society marked by flexible social standards and casual morals. In The Persian Letters, Montesquieu went so far as to say that

at the court, in Paris, or in the provinces,…these women are all in each other’s secrets, and form a sort of republic, the members of which are always busy aiding and serving each other; it is like a state within a state.8

During the reign of Louis XVI, public opinion turned against this feminization of power, setting off a brutal reaction; Marie Antoinette was its first victim. Previous queens of France, Fumaroli points out, had lived retiring lives, leaving it up to the royal mistresses to spend the state’s money, brighten up court life, and entertain the king. The unaccustomed aspect of Marie Antoinette’s situation lay in the fact that Louis XVI was a loving and faithful husband, while quite recklessly—because she was doing it more to dispel her boredom than to amuse Louis XVI—she had taken on two entirely incompatible roles: that of arbiter of elegance and, at the same time, that of dynastic queen.

What is more, she condemned herself in the eyes of the French populace by her lavish spending; she further deprived herself of the protection of the more traditional circles at court through the excessive indulgence she displayed toward her favorites. The hours spent in the company of her intimate women friends, especially in the Petit Trianon, which had been declared off-limits to the king himself, infuriated the courtiers who were excluded and only fed the flames of the most fanciful rumors of imagined debauchery. Obscene pamphlets concerning the pursuits of the tribades de Trianon—the “butches” of the Trianon—circulated throughout the city. The demonization of the queen was underway.

The government, well aware of the danger inherent in the queen’s deteriorating image, hoped it could turn matters around by commissioning a large canvas of Marie Antoinette surrounded by her children. A Swedish painter having failed to complete the task successfully, Vigée Le Brun was called in.9 She had secured a monopoly over the image of the queen.

The assignment had its risks. First off, the political stakes were high; second, a canvas with multiple figures and on a grand scale posed a considerable challenge. Self-taught artist that she was, Vigée Le Brun had never painted anything other than individual portraits or self-portraits with her daughter. How could she determine the proper composition of such a painting? She went to the artist Jacques-Louis David for advice, and he suggested basing the work on a Raphael Holy Family. But won’t people accuse me of plagiarism? the portraitist asked uneasily. Bah, David responded, once you’ve fixed it all up with fashionable apparel and modern furniture, no one will ever suspect that you took a composition by Raphael as your model.

The painting demanded two years of work and was exhibited in 1787. Coiffed with an elaborate headdress that sported ostrich plumes, garbed in a red velvet dress, Marie Antoinette holds her youngest son in her lap and her daughter snuggles against her shoulder, while the Dauphin points to an empty cradle, an allusion to the last-born girl, who died while the painting was being done.

The political objective was not attained and the portrait failed to arouse any stirring of sympathy for the queen. It was thought that her expression was chilly, anything but maternal. There was no eye contact among the four subjects. The hostility toward the queen did not abate. She was seen not as a mother but as a dominating spouse and the canvas only fanned the flames of a virulent reawakening of political, moral, and social misogyny directed primarily at Marie Antoinette.

As for Vigée Le Brun, her growing wealth and her ties to the unpopular queen made her a vulnerable target. Did she fully understand, Fumaroli wonders, the symbolic power of that

superb manifesto of manly revenge, in the style of antiquity, that her friend David exhibited at the 1785 Salon: The Oath of the Horatii,…where the overwrought women are thrust back with their children into their housewifely sphere and where the republican heroes, brandishing their swords, seem to defy the world of women…

—the world of women that Vigée Le Brun had so glorified?

The political atmosphere worsened rapidly and she felt herself to be targeted directly when she found insults scrawled on the walls of her house. On July 14, 1789, the Bastille fell. On October 6, Versailles was overrun and the royal family returned to Paris as prisoners of the people. That same evening, Vigée Le Brun left Paris for Italy with her daughter. She was not to return for twelve years.

Having fled the French violence, she discovered, to her relief—over the course of a lengthy exodus that took her from one court to another, in a Europe suffused with the spirit of the French eighteenth century—that everywhere she went she was welcomed warmly. Potential clients sought her out persistently, in spite of the stratospheric fees that she staunchly refused to lower. She spent six years in Russia, the furthermost point of her exile.

She returned to France, under the Empire, in 1802, in possession of a considerable fortune. Her husband, who had shrewdly divorced her during the Revolution in order to avoid the confiscation of his assets, welcomed her back to their longtime home and they resumed living together, bound more by interest than by affection.

She went back to work, but fashions had changed. Vivant Denon, director of the Louvre, wrote to a friend, “Le Brun is…no longer the leading female artist of France. There are other astonishing ones who are quite young.”10 She traveled to London in 1803 and painted, among others, the Prince of Wales and Lord Byron. When she was rudely criticized by a fellow painter, John Hoppner, she replied with great dignity:

However much you might disparage my pictures, all the worst you could say of them would be less than I think. I do not suppose that any artist imagines he has attained perfection.

Upon her return to France, though saddened by the gloomy atmosphere of a society once so gay and free, her enthusiasm for her work did not wane. Commissions never stopped. She also traveled to Switzerland, where she devoted herself to landscapes, but only a few examples of this aspect of her work have been preserved, though she probably did over two hundred, mainly in pastels. At the age of nearly eighty, having finished her last portrait three years earlier, she finally sat down to write her memoirs.

Written with a light touch, the memoirs make clear all their author’s energy and optimism. The book is one last portrait of a privileged Europe bound to disappear, a canvas from which she dispels the shadows. It was an unquestionable success but a certain whiff of frivolity offered the critics a tempting target. One hundred years later, the book felt the sting of Colette’s sharp pen. She wrote a sarcastic parody, mocking the artist’s stunning volume of production, and her gift for holding tragedy at arm’s length.

Vigée Le Brun was pretty, talented, intelligent, and rich. That may not necessarily be the ideal formula for attracting universal approval. To judge from her first biographers, men saw her as a society portraitist whose art owed too much to the “influences” of her male entourage, or else “a charming woman, a charming artist, with a skill” for finding pictorial formulas that stir the emotions and sufficiently canny to “dictate her judgments to posterity.” And in fact, as André Blum noted in his 1919 biography, there is “an element of contempt…in the glory that men assign to women. They celebrate nothing of them but their beauty.”11

Even so, women haven’t always been much more charitable, and they’ve contributed to what Baillio calls her bad reputation. The memoirist Mme de Boigne, in a surprising judgment, found her “rather foolish.” Simone de Beauvoir saw her as a narcissist, and said she “never wearied of putting her smiling maternity on her canvases.” An odd line of attack, considering that she painted only two self-portraits with her daughter.

Vigée Le Brun certainly poses a problem for any feminist interpretation, inasmuch as she never felt her femininity as a hindrance to her career and her creativity. The best way to judge her however is to look at her work. At the Metropolitan Museum exhibition, one can see her audacious use of color—in the portrait of Countess Samoilova she uses side by side crimson, red, and orange—as well as the prowess and imagination with which she renders fabrics, jewels, and headpieces, the most amazing of which, placed on the head of Princess Golitsyna, is a turban transfixed by an aigrette. One also sees the masterful treatment of light and shadows on her sitters’ faces as well as the faintest vein throbbing on a forehead.

One might weary of rooms filled with portraits of young and smiling ancien régime beauties, the only portraits of old ladies included in the exhibition being those of the two surviving daughters of Louis XV, if it were not for the portraits of men interspersed with them. These portraits show the vigor and psychological insight of which Vigée Le Brun was capable when the sitter’s face suggested intelligence and strength of character. The vividness of the portrait of Calonne, Louis XVI’s minister of state, the air of authority of Alexandre de Crussol, and the moving honesty one recognizes in the portrait of her friend and supporter Joseph Vernet are proof of the scope of her exceptional talent.

—Translated from the French by Antony Shugaar

-

1

Richard Dorment, “Working Girl,” The New York Review, February 15, 1990. ↩

-

2

In English, one may read Memoirs of Madame Vigée-Lebrun, translated by Lionel Strachey, with an introduction by John Russell (Dodo Press, 2010), and The Memoirs of Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, translated by Siân Evans (Indiana University Press, 1989). ↩

-

3

Joseph Baillio, Elisabeth Louise Vigée LeBrun, 1755–1842 (Kimbell Art Museum, 1982). ↩

-

4

Letter to her mother, November 16, 1774, from Correspondance secrète entre Marie-Thérèse et le comte de Mercy-Argentau (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1874), p. 254. ↩

-

5

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Souvenirs, 1755–1842 (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2008), p. 772. ↩

-

6

Geneviève Haroche-Bouzinac, Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun: Histoire d’un regard (Paris: Flammarion, 2011), p. 85. ↩

-

7

See Pierre Rosenberg and Paul Falla, “A Drawing by Mademoiselle Vigée Le Brun,” The Burlington Magazine, December 1981. ↩

-

8

Montesquieu, Persian Letters, CVIII, quoted by Fumaroli, “Mundus muliebris”: Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, peintre de l’Ancien régime féminin, p. 13. ↩

-

9

The commission was issued not by the queen, as was the case with all the other canvases, but more officially by the Bâtiments du Roi (literally, the King’s Buildings), which were responsible for all work ordered by the king. ↩

-

10

Vivant Denon, Lettres à Bettine, letter dated October 24, 1802 (Arles: Actes Sud, 1999), p. 507, quoted by Haroche-Bouzinac, p. 394. ↩

-

11

André Blum, Madame Vigée-LeBrun, Peintre des Grandes Dames du XVIIIème siècle (Paris: H. Piazza, 1919), p. 5, quoted by Haroche-Bouzinac, p. 11. ↩