As he enters into his tenth decade, his sixth of literary production, it seems safe—but also important—to nominate William Gass as our greatest living champion of the sentence. A scholar of its innumerable variations, he has devoted untold numbers of pages to pondering its metaphysics. And he has himself, of course, practiced everything he has preached. He writes, he says, for the ear, and does so contagiously, working the sources of rhythm and cadence as he rolls out his variegated verbal brocades. He is never unaware of his materials, and never afraid to go for effects that might, in W.H. Auden’s words, “bring down the house.” Try reading William Gass and then keeping him out of your own sentences.

Stylistically it has been this way from the start in his fiction—from Gass’s first published book, Omensetter’s Luck (1966), a portrait of a charismatic man in nineteenth-century Ohio, down through the subsequent works, like his vast and venting novel The Tunnel (1995), in which a Holocaust expert fears that his wife will discover his cruel descriptions of their life together and begins to dig a tunnel out of his basement, and the recent Middle C (2013), about a middle-aged man whose family fled Austria by pretending to be Jewish. This is no less true in the steady minting of his sui generis essays, which have now been gathered into seven collections. Though he has been taken to task in some critical quarters for linguistic overexuberance, these same works have won Gass honors too numerous to cite—three of the essay collections alone have won the prestigious National Book Critics Circle award.

Trained as a philosopher (he studied with the analytic philosopher Max Black and—briefly—with Ludwig Wittgenstein at Cornell), Gass taught philosophy for many years at Washington University in St. Louis. His philosophical interest centered primarily on language, and one of his achievements has been the translation of aspects of that preoccupation into the literary. Gass credits his reading of Gertrude Stein as his awakening to the structural implications of literary expression. As he said in an interview with The Paris Review:

When I started to examine what she was up to, I realized that I had to begin to get a feel, the way a painter would, of what happens when you try a sentence this way or try it that. To write sentences out of context is a fool’s business, but I set about doing the fool’s business. You can’t really talk very sensibly about the content of a sentence out of the context of its use, but you can talk a lot about the form of the sentence and how the forms are interlaced and how they interact within a sentence.

Gass cannot say enough about the great sentence maximalists—about Stein, Henry James, Malcolm Lowry, Ford Madox Ford, James Joyce, Marcel Proust—or about the core mysteries of sense making, how it is that words rightly aligned create, or simulate, the inner life in both writer and reader. The titles of his collections of reviews and essays are revealing in this regard. Fiction and the Figures of Life, The World Within the Word, Habitations of the Word, A Temple of Texts, Life Sentences—all propose the fundamental relation between language and experience. The idea that language constitutes the world seems to be the foundation of Gass’s aesthetic, or, to change metaphors, its driving impulse. As he expresses it in the essay “The Music of Prose”:

No prose can pretend to greatness if its music is not also great; if it does not, indeed, construct a surround of sound to house its meaning the way flesh was once felt to embody the soul, at least till the dismal day of the soul’s eviction and the flesh’s decay.

That “surround of sound” is a perfect instance of Gass’s ever-vigilant and ever-opportunistic ear, the way the word “surround” in fact surrounds—encloses—the word “sound,” exactly mirroring the sense of what’s being said.

Life Sentences: Literary Judgments and Accounts is Gass’s most recent collection of essays. Though there are strong continuities with his previous books, this group displays a broader range of the essayist’s register than the others. His full-on lyric-immersion attack is well represented in substantive essays on Nietzsche, Kafka, James, and Lowry, but he also includes more accessible autobiographical musings at one end—recollections of his life in libraries and among books, of his father and baseball—and a suite of denser philosophical reflections (on form, mimesis and metaphor, and sentence structure) at the other.

In “Retrospection,” one of the handful of previously unpublished pieces, Gass ventures his own self-assessment. He begins by citing an epitaph that the poet Howard Nemerov composed for himself:

Advertisement

Of the Great World he knew not much,

But his Muse let little in language escape her.

Friends sigh and say of him, poor wretch,

He was a good writer, on paper.

Nemerov’s words give the writer courage. Rather than focusing on “the messes I made or on the few fragile triumphs I may have enjoyed,” writes Gass, “I find it less painful to concentrate on the kind of thing that concerned me.” He then itemizes, for exploration, seven of what he calls “preoccupations…bad habits…quirks” in his own writing. “They are: naming, metaphoring, jingling, preaching, theorizing, celebrating, translating.” A motley-seeming basis for literary self- assessment, but these terms somehow allow him the particular access he needs. And indeed, as the essay starts to unfold, we see how these select aspects of his practice allow him to address certain criticisms, clarify intents, and place emphasis on the things he deems most important.

“Naming” is the first. The word, which reminds Gass of Adam’s identifying of the animals in the Bible, sets him up both to articulate the core mission of his art and to reply to what he sees as a common criticism made of his work. “Critics still write of me as if my interest in words was an aberration,” he declares. I don’t think it’s the interest that the critics have questioned so much as the writer’s frequent drift into a baroque maximalism of expression, but never mind. Gass is conducting us into the laboratory and asserting a primal principle of his enterprise: his belief that the act of naming—and writing is nothing but naming—does not point to the world so much as bring it into being. But writing, he confesses, “has almost always been difficult for me, something I had to do to remain sane, yet never satisfying in any ordinary sense, certainly never exhilarating, and never an activity that might satisfy Socrates’ admonition to find a Logos for my life.”

It is somehow disconcerting that after all these years Gass should continue to see himself as an exile, a skeptic, even as his long life’s work has been so insistently about the creation of structures of meaning from language. But how is one to argue with another’s subjective disclosure?

The second of these “preoccupations,” writes Gass, is “whoring and metaphoring.” The coining of likeness, he admits, is irresistible to him. Though having said as much, he offers surprisingly little reflection, is content merely to point out what is for him a successful use of metaphor from his early story “Order of Insects,” in which a woman whose home is filled with cockroaches begins to develop admiration for them. But for a real exploration of this core operation of creative consciousness, we need only turn to the later essay “Metaphor,” where Gass begins with the word’s etymology and moves into the most far-reaching inquiry. If we think metaphoring is some simple way of asserting one thing as being another, then we are in for some pages of heady concept-parsing—a favorite Gass tactic—as instances from Homer and others are stripped down to their operative components, and then assessed for how they model their respective realities. The business gets quite opaque in places, until Gass reaches the liberating crescendo of the last passage, writing:

Metaphors will possess scope and depth; they will be condensed or expansive; and they will exhibit those qualities of perception, emotion, thought, energy, and imagination that every consciousness enjoys when it is fully functioning. They will sense something; they will feel something; they will think something; they will want something; and they may imagine almost anything.

Of the others in his list, theorizing and celebrating seem to be the more important rubrics for Gass, maybe because they express the tension of their polarities in so much of the work.

“Theorizing” gets him reflecting on his long novel, The Tunnel, and its obsessive impetus to push aside all niceties and show humanity at its flagrant worst. Gass’s protagonist Kohler excavates the Holocaust through his researches and makes it his mission to rub the collective nose in the horrors of it all. This impulse is reprised in shorter form in Life Sentences in “Kinds of Killing,” a long essay about abominations of World War II, where he writes of “death that opened from the earth as if every furrow were a mouth, death by whispered denunciation, death by every means imaginable” under the Nazi regime. We never mistake Gass for a documentarian, no matter how many instances of something he elaborates for us. His aim is always to philosophize it, to assess what truth, or what Platonic construct, may lie behind it all. So after reciting an extended catalog of Holocaust horror from The Tunnel, he pulls back to reflect:

Advertisement

I have taught philosophy, in one or other of its many modes, for fifty years—Plato my honey in every one of them—yet many of those years had to pass before I began to realize that evil actually was ignorance—ignorance chosen and cultivated—as he and Socrates had so passionately taught; that most beliefs were bunkum, and that the removal of bad belief was as important to a mind as a cancer’s excision was to the body it imperiled.

How does this “theorizing” connect to “celebrating”? Determine this and much about Gass comes clear. He contains polarities, multitudes. “Life may be a grim and grisly business,” he asserts, “but the poet’s task and challenge remains unchanged.” To praise. With this, he goes right to Rilke, one of his master-spirits, whom he celebrated in his 1999 book Reading Rilke. Does this then represent a contradiction? If we deem language as merely mapping the world, yes. How could we wring praise from an existence Gass has figured as a colossal botch? But if language creates the world, then what must be celebrated is the fact and the basic possibility of that making, even as he admits that “neither you nor your weaknesses, nor the world and its villains, will have been vanquished just because now it is in syllables and sentences where they hide….”

Again, whence the celebration? He answers this with his reflection on translating, drawn from his Reading Rilke:

The poem is thus a paradox. It is made of air. It vanishes as the things it speaks about vanish. It is made of music, like us, “the most fleeting of all” yet it is also made of meaning that’s as immortal as immortal gets on our mortal earth…because the poem is a state of the soul, too (the soul we once had), and these states change as all else does,…when rightly written they are real…are with a vengeance; because, oddly enough, though what has been celebrated is over, and one’s own life, the life of the celebrant, may be over, the celebration is not over. The celebration goes on.

For all of his lingering on the unspeakable, it is finally this sense of celebration that attends Gass’s judgments and accounts in these essays, whether he is extolling the linguistic profundity underlying Gertrude Stein’s primer-simple pronouncement “I am I because my little dog knows me”; or catching a big-picture distinction in an incidental aside: “To Balzac, matter has a weight all its own; to Proust, matter has weight only when metaphored by mind”; or raising the shipwreck that was Malcolm Lowry from its seabed through a conceit of cinematographic annotations. (For example, he writes: “Set the scene: in 1949 Malcolm Lowry with the collaboration of his wife, Margerie Bonner, begins a film script for F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel Tender is the Night.”) Gass can be playful, but his inventions always serve the deeper cause. Lowry sought to make a world, and this is what Gass is exalting.

It all does finally come back to sentences, to language, and to form. “I believe that the artist’s fundamental loyalty must be to form,” he writes in his notes on theorizing, “and his energy employed in the activity of making.” Gass’s inclusion of his three Biggs Lectures in the Classics brings gravitas to the end of the book, moving deep into Plato and Aristotle, taking up questions of being and imitation with a genuine urgency.

In all this thinking about thought, one does begin to discern a rationale for Gass’s own artistic process, as it applies to fiction as well as the making of essays. Ever the philosopher, he takes seriously the idea that if we grant the unattainable perfections of Platonic form, all knowing and action are imperfect and partial. Unable to claim secure possession of ourselves in the light of some truth, he suggests we instead seek understanding through mimesis, through acts of projective imitation, over and over putting ourselves into the place of everything we encounter—in our living and in our art.

This is seen most clearly—and quite playfully—in “Kafka: Half a Man, Half a Metaphor,” Gass’s essay on several recent biographies of Kafka. Here he looks to ventriloquize not the writer but the writer’s creation, the “bug,” thereby carrying out a second-order impersonation, a mimesis, in effect, of Kafka’s own Gregor Samsa. “In my writerly guise,” he writes, voicing Kafka,

my pages will be as shocking as my present prehistoric carapace. I want to publish principally to prove to my father I can be a success at something. But not in my role as a writer, rather in my role as a son.

The projection allows Gass to get deep into his subject, which is in fact the question of the impetus behind the taking on of roles.

The aesthetic of empathic impersonation is fundamental to fiction—indeed, what else is fiction but a vale of refracted self-making (Madame Bovary c’est moi…)?—but in his latest collection of stories, Gass extends his imagination’s reach past the human form and past the insect form, right into the realm of actual objects.

Two of the stories in Eyes are narrated directly through the persona—or maybe we should say “objecthood”—of an ostensibly unsentient thing. They are tour de force instances of a writer working a constraint. “Don’t Even Try, Sam,” is a whimsical narration by the piano that was used in Casablanca, while “Soliloquy for an Empty Chair” offers the plural perspective of a row of chairs in a barbershop. The first performs a lower degree of difficulty, as Gass trades on the reader’s familiarity with the basic business of the film—its characters, the famous actors who play them, the important plot turns. Moreover, the instrument is given a watchful awareness that is in effect a kind of psychological personhood. “Twenty-two. It’s the number Helmut Dantine—I worked with him once in later years—handsome devil—it’s the number he’s told to bet in order to score at roulette. Rick, a real sog heart, lets the Bulgar newlywoos win the dough for their passage out of the picture….”

Gass is working a version of the old “if walls could talk” conceit, and the surprises and satisfactions are those of altered vantage. We get perceptions about humans, but they are filtered through an unusual constraint; they produce the short-circuiting of any customary responses. It’s a bit like the game that was played with Kafka’s bug, but with a lighter impact.

“Soliloquy for an Empty Chair” raises the technical bar somewhat, for the mise-en-scène cannot be summoned, but must be filled in stroke by stroke. Also, the perceptions of event are now severely reduced. These chairs can only testify to what their literal position as chairs has given them access to. They realize, for example, that the owner of the barbershop also runs an after-hours poker room, but they do not understand what happens within it. There is an event, something that in the human frame appears quite dramatic, but the reader must strain to imagine it from the chairs’ limited account.

Interesting as it is to view these pieces as manifestations of a philosophically motivated impulse to extend—and alter—the human scope, they don’t compel a deeper engagement. Rather, they help buttress the argument that the power of fiction is finally rooted in character. Human character—for of course part of Gass’s stratagem is to endow the objects with enough familiar sentience to hold our amused attention. But amused attention is not necessarily engagement.

Creating character in the traditional sense has never been Gass’s deepest interest. Even in the stories of his influential first collection, In the Heart of the Heart of the Country (1968), he found ways to subvert the traditional expectation. The title story depicted one man’s heartbreak through absolute indirection, allowing his exile’s itemizing perceptions of locale to suggest the scattered dots of his situation and asking the reader to do the connecting. He has come to a small town in Indiana to escape his agony. “It’s as though I were living at last in my eyes,” the narrator says, “as I have always dreamed of doing, and I think then I know why I’ve come here: to see, and so to go out against new things—oh god how easily—like air in a breeze.” Another, “Order of Insects,” which Gass refers to in his essay on metaphor, dramatized a woman’s collapsing sense of self through her growing obsession with the subtle body formations of dead beetles. “The first I came on looked put together in Japan; broken, one leg bent under like a metal cinch; unwound.” By and by the reader finds the equivalences between perceptions and repressed feelings.

But if he is not interested in creating delineated fictional characters, Gass is fascinated by the miasmas of consciousness—the sprawl of sentience (and sentence), some of that “blooming, buzzing confusion” that William James called the baby’s early experience of the world, but that can also capture the movements of exacerbated consciousness, its bursts of memory and association, its often erratic passage from thought to thought. I cite “blooming” here with its Joycean suggestion, for Gass looks to immerse his reader in a full tidal experience, whether it be that of the narrator in his early novella “The Pedersen Kid,” delirious from exposure and fear in the teeth of a midwestern blizzard in which his neighbor’s young son has nearly died; or Kohler, The Tunnel’s Holocaust scholar who is losing his grip.

Eyes includes several of these extended psychic immersions. One story, “Charity,” tracks that impulse back through a densely woven root system of conflicting motives. The narrator, Hardy, works as a kind of traveling corporate enforcer, paid to remind scammers and would-be scammers of his company’s muscle. But his daily dealings are increasingly cut through by memory flashes from childhood, episodes that reveal over and over the hypocrisies underlying his family’s ostensible do-gooderism, until a final interaction with a “charity case” breaks him open completely:

He drew out his billfold and emptied it of money. I dunt wunt your munny, she said in a voice as flat and hard as the hand that subsequently slapped him when he pushed a fistful of cash in her direction. The sting went everywhere his bones went.

But it is Gass’s opening novella, “In Camera,” that carries the day. Here we find an imagining so insistently strange and particular that we cannot but wonder just how it is that imagination mines experience—or just how language brings worlds into being.

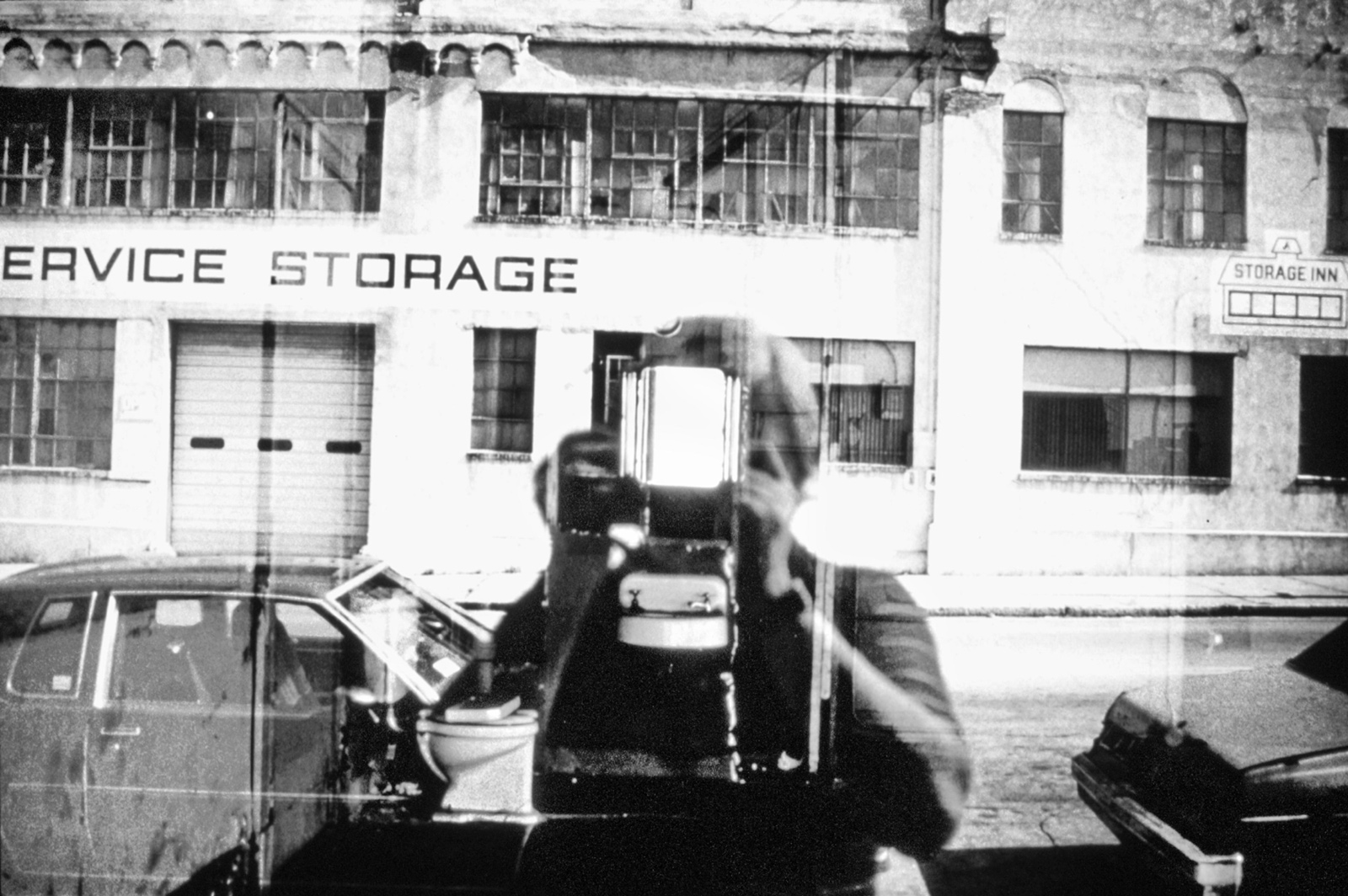

The novella is orchestrated as a kind of Beckettian to-and-fro between two consummate oddballs—Mr. Gab, who runs an unkempt establishment offering rare photographic prints, and Mr. Stu, his assistant, who starts his employment with the ineptitude of the isolated Kaspar Hauser, but gains in savvy and comprehension as the narrative unfolds. We see little conventional plot development. Though there is an inconclusive intrigue that has to do with the status and provenance of various rare photographs and some idea that Mr. Gab might be coming under investigation for their possession, the uncertainty is only part of the murk of the piece.

But perhaps there is a logic. We can take the title “In Camera” on several levels. A camera is, of course, a room—and nearly the whole work does unfold in the dark spaces of Mr. Gab’s shop. But a camera is also a…camera, and it seems quite possible that Gass, with his whimsical fondness for unusual constraint, has created a whole work revolving around photography while at the same time making a narrative that serves as a simulacrum of the camera itself, with Gab and Stu, rendered through their thoughts and perceptions, together comprising a kind of verbal film that is absorbing and recreating an image of the world.

Though scarcely anything can be said to “happen,” the ruminative movement of the story seems carefully pitched to the rhythms of slow visual contemplation. So the eye lingers over a photograph by Josef Sudek:

Rows of insulators perched like birds for the night on faintly wired poles, but so composed…made of mist…composed so that the bushes at one end of the panoramic rhymed with the tree limbs at the other; thus the blacks beneath held up the grays above, so the soft glow of the failing sun, which could be still seen in the darkening sky, might lie like a liquid on the muddy lane…and Mr. Gab would inhale very audibly…because only once had the world realized these relations; they would never exist again; they had come and gone like a breath.

There is an undeniable feeling of the subject emerging into clarity by degrees, like an image in a chemical bath, even as Gass is also carrying out a study of the art, maybe in a sense all art:

Mr. Gab was a stickler. His ideal was the perfect picture taken on the wing with one shot, and allowed to emerge from its development like a chick its egg, so that one saw not just the subject supremely rendered but a testimony to the unerring fineness of the photographer’s eye; an eye unlike the painter’s, he claimed, because the painter constructed; the painter made up his image as if the canvas were a face; while the photographer sought his composition like a hunter his prey, and took it away clean, when it was found, to present in its purity, as the result of an act of vision, the sort of seeing no one else employed, what Mr. Gab called “sling-shot sight.” …The photographer came, saw, and shot in a Rolleiflex action, in one unified gesture like waving off a fly.

Swept up as we are in cadence and precise exposition, we should not forget that it is the writer’s mind that depicts this grace of finding; and that we are, as readers, being nested inside the various conceits he has figured. Not the least of these might be that it is our reading action itself that is developing the image there in the tray, bringing the whole fabulous murky world into the light.