Between April 6 and October 31, 1913, the city of Ghent in northern Belgium hosted an Exposition universelle et internationale. For this provincial city it was a stupendous effort. The Gent-Sint-Pieters station, still the city’s main railway terminus, and the Central Post Office, with its eclectic mix of Gothic Revival and neo-Renaissance styles, were finished just in time for the festivities. A special airmail service was laid on as a publicity gimmick (a practice pioneered two years before, at the United Provinces Exposition in Allahabad, British India).

Across 320 acres, the architects of the exposition assembled a panoply of national pavilions and themed displays focused on every conceivable product of human ingenuity, from locomotives, telegraph lines, and industrial machines to weapons, artworks, and cigarettes. In the “Rue du Caire,” visitors could immerse themselves in a garish reconstruction of an Oriental bazaar peopled by merchants in exotic costumes. “Old Flanders,” a faux-medieval village, evoked the historical depth of Flemish identity, which was then entering a phase of cultural revival.

This was also the last exposition of its kind to include displays of live humans from the colonial periphery, though in Ghent these were less prominently situated than at the Paris exposition of 1900. Next to the exhibition dedicated to the French colonies was a “Village Sénégalais” in which West African men and women prepared traditional foods using ancestral implements. In an enclosure incongruously located on the edge of “Old Flanders,” Europeans could gawk at fifty-three Igorot tribespeople from Bontoc, in the Mountain Province of the northern Philippines, pretending to go about their daily tasks. (One of them, a twenty-eight-year-old man named Timicheg, died of tuberculosis during the exhibition; today, one of the city’s rail tunnels is named after him). “The Exhibition,” a contemporary Ghentish enthusiast declared, would be

a new and luminous signpost on the road towards progress where humanity halts, gathers itself, reflects, and judges the state of global civilization, in order to advance more surely to new and decisive triumphs.

Among the millions of visitors (estimates range from four to nine million) was the Scottish philanthropist and pioneering town planner Patrick Geddes, who was impressed by what he saw. In the large display dedicated to the Belgian Congo, Geddes recognized a salutary determination to cleanse the country’s public life of the horrors perpetrated under King Leopold, who had died in 1909. He appreciated the exhibition’s artful juxtapositions of past and present, which helped “the best minds” to distinguish “heritage” from the mere “burden” of the past. But most important of all was the exposition’s international purpose, which was to project the “immense importance” of Belgium as a “Key-stone State” whose “very material and military weakness, in the midst of great armed Powers, gives her an advantage of common appeal to them all.” Scarcely a year after these words were written, Ghent was under German occupation.

It is hard to think of an event more richly suggestive of the condition of Europe—or at least of its elites—at the dawn of the twentieth century. The past was swiftly receding (though the good bits, happily, could be recaptured as “heritage”) and the present was a charged threshold to a brilliant future. From the high ground of modern European life, one could comfortably “judge the state of global civilization.” The intensity of the self-belief is extraordinary.

And yet, with eyes sharpened by hindsight, we can discern easily enough the stress fractures in the system. When King Albert I and Queen Elisabeth opened the exposition on April 26, 1913, many of the displays were still months from completion because a strike for universal male suffrage among the laborers on the site had disrupted the construction. The recently launched campaign to establish Ghent University as a center of Dutch-language culture had antagonized the French government, which demanded the lion’s share of exhibition space (90,000 meters in all, distributed across several halls). The aim was not just to project the authority of francophone culture in Belgium, but also to out-exhibit the Germans, who came close to staying out of the exposition altogether.

These tensions capture in miniaturized form three of the themes that animate To Hell and Back, Ian Kershaw’s magisterial history of Europe in the years between 1914 and 1949: class conflict, the politics of ethnicity, and the geopolitical struggle over space. World War I would transform all three into forces of unparalleled destructive power. Kershaw’s fourth theme, a protracted crisis of capitalism, would only emerge after 1918, but it, too, was a consequence of the conflict that George Kennan called the “seminal catastrophe” of the twentieth century.

Kershaw’s chapter titles evoke a turbulent landscape: “On the Brink,” “Dancing on the Volcano,” “Gathering Shadows” (the sun is setting on this landscape), “Towards the Abyss,” “Out of the Ashes.” The metaphors are seismic, igneous. In the book’s darkest chapter, “Hell on Earth,” world and underworld have changed places, rupturing the surface of reality. The energies transforming the scene come from within the landscape itself: his book, as Kershaw makes clear, is a narrative of Europe’s self-destruction, focused tightly on the European mainland and particularly on Central and Eastern Europe, where the violence was most intense and protracted.

Advertisement

There are doubtless other ways of framing the narrative. A more world-historically attuned account might open at the turn of the century rather than in 1914, focusing on flashpoints on Europe’s global periphery: the Spanish–American War of 1898, for example, whose deep impact on Spain’s nationalist elites still reverberated in the Spanish civil war nearly forty years later; or the international expedition against the Boxer Rebellion of 1899–1901, which heightened tensions among the European colonial powers on the Chinese littoral; or the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, which shifted the focus of Russian foreign policy, realigned the European alliance system, and heralded the rise of a rival East Asian imperialism that would ultimately bring the United States into World War II. Following this approach, one might trace the crucial transition to the years 1911–1913, when Italy’s unprovoked attack on Libya triggered a wave of wars in the Balkans, creating mechanisms of escalation that would help to transform the summer crisis of 1914 into a continental conflict. This, one might argue, was the moment when the destructive energies projected by Europe onto the imperial periphery were deflected back onto the continent itself.

The forces that devastated the continent between 1914 and 1949 germinated, as Kershaw points out, within Europe itself. Starting in the 1890s, mass movements of left and right heralded the later escalation of class conflict into murderous violence. The fashionable esteem for eugenics reflected the primacy of hygienic utopias over humanitarian individualism. The atrocities committed by all parties in the course of the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913 anticipated later efforts to “cleanse” conflicted territories of unwanted ethnic “aliens.”

In Eastern and Central Europe, the appalling violence against Jews already presaged the horrors of the 1940s. In the aftermath of the failed Russian revolution of 1905, Kershaw writes, three thousand Jews were murdered in 690 pogroms in the western territories of the Russian Empire. In Odessa alone, eight hundred Jews were murdered, five thousand injured, and a hundred thousand left homeless. In the rising tide of anti-Semitism Kershaw rightly sees a subtle barometer of broader political transformations.

Raising the curtain on the eve of the conflict highlights the threshold character of World War I. In 1914, Europe stepped through the looking glass. However ominous the events of the pre-war years, they never came close to anticipating the carnage that would follow. (Europeans might have been clearer-sighted about the horrors ahead if they had cast their eyes farther abroad—at the American Civil War, for example, or the War of the Triple Alliance of 1864–1870 between Paraguay and its neighbors, in which 90 percent of the male population of Paraguay perished.)

Kershaw evokes the impact of the war in its opening phase with a concise analysis of the figures of the dead, wounded, and captured. British losses by the end of November 1914 were already at 90,000, more than had been initially recruited to fight. By the Christmas of 1914, over a quarter of a million French soldiers were dead. German losses over the same period were 800,000, including 116,000 killed in battle, more than four times the total mortalities of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871. And Russian losses were the highest of all: during the first nine months of the war, Russia lost just under two million men, of whom 764,000 were captured. Although the intensified killing of the great battles would set far higher records of concentrated lethality (British and Dominion troops lost 57,470 men on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, for example), casualties as a proportion of the total numbers engaged would never be as high as in these terrifying early months.

From the very beginning, Kershaw reminds us, civilians were caught up in the violence whenever armies found themselves on foreign territory: in Belgium, advancing German troops killed, brutally maltreated, or deported over six thousand civilians, including women and children; similar depredations took place in East Prussia after Russian forces crossed the eastern borders of the German Empire. The Austrians summarily executed at least 3,500 Serbian civilians, and the advance of the Russians (and especially of Cossack units) into Austrian Galicia brought waves of rape, murder, and deportation, especially to the region’s Jews, of whom 50,000 were deported to Russia, many of them winding up in Siberia and Turkestan.

For civilians in the contested territories of Central Europe, the war brought an era of ravages and devastation more reminiscent of the violence and destruction of the Thirty Years’ War of 1618–1648 than of the concentrated horror of the trench warfare on the western front. Kershaw cites the memoirs of Jan Słomka, mayor of the Polish village of Dzików in what was then Austrian Galicia. Within a year of the war’s outbreak, the Austrian armies passed through Słomka’s district five times, the Russians four times. Major battles took place nearby and there were two Russian occupations. Nearly three thousand farms and homes were destroyed in the surrounding areas and huge areas of woodland were burned, cut down, or destroyed by artillery fire. As happened elsewhere, the Jews of Dzików were in special peril. When the Russians arrived, they were gathered together and publicly whipped. In a village nearby, five Jews were hanged for allegedly hiding weapons; two more were hanged by the roadside because they were suspected of spying.

Advertisement

In four powerful chapters, Kershaw scrutinizes the precarious peace that followed the armistice of November 1918. The war did not end in 1918, but rather spilled over into ultra-violent civil and territorial conflicts. When 15,000 armed Communists and fellow travelers seized control of the police stations and rail terminals of Berlin in March 1919, Gustav Noske, the Social Democratic minister of defense, mobilized 40,000 government and Freikorps troops who used machine guns, field artillery, mortars, flamethrowers, and even aerial strafing and bombardment to put down the insurgency. By March 16, when the fighting came to an end, 1,200 people were dead.

In Hungary, too, the “Red Terror” of the Communist leader Béla Kun was followed by a more lethal “White Terror” that claimed around 1,500 lives. Across much of Central and Eastern Europe, Poles, Lithuanians, Latvians, Germans, Czechs, Hungarians, Ukrainians, and Russians clashed in bitter struggles over newly drawn political borders. And here again, it was the Jews who bore the brunt of the worst violence: between 50,000 and 60,000 Jewish civilians were killed between 1918 and 1921 in Ukraine alone.

To be sure, the later interwar years saw a degree of stabilization. After the shocks of political revolution, inflation, and hyperinflation between 1918 and 1923, Germany, whose stability, Kershaw notes, was “vital to the peaceful future of the European continent,” entered a period of economic growth and relative tranquility. And yet even in the good years, class antagonisms continued to corrode political consensus, and the resulting deadlocks were worsened by the downturn in the economic climate. It was the impossibility of reconciling employers to the need for increased unemployment benefits in the economic crisis atmosphere of 1929 that finally broke the chancellorship of Hermann Müller, opening the door to the sequence of increasingly authoritarian manipulations that would eventually bring Adolf Hitler into the government.

Kershaw develops a range of arguments about why democracy proved so resilient in some settings and so fragile in others. In Britain, Ireland, France, and Scandinavia, high levels of cultural and political cohesion militated against fragmentation. In Belgium and the Netherlands, the crystallization of political society into distinct “pillars” (Catholic, socialist, and liberal) limited the appeal of extremist political doctrines. In France, the left overcame its internal divisions in time to establish the Popular Front of 1936. In Spain, by contrast, it was the traditionally highly fragmented right that belatedly achieved unity under General Franco. Even so, it proved surprisingly hard for the nationalist rebels of 1936 to uproot the democratic Spanish Republic. By April 1, 1938, when Franco declared the war over, 200,000 had died on the battlefields of Spain. Republican radicals had murdered over six thousand members of the clergy. There had been furious nationalist reprisals against republicans in the occupied areas and a further 20,000 republicans were executed after the war had been won. In all, well over a million (from a population of 25 million) suffered death, torture, or imprisonment.

Kershaw contrasts the extraordinary dynamism of the Nazi, Fascist, and Soviet regimes with the reactionary dictatorships that took root in many other European states. The drab Greek dictator Ioannis Metaxas made do without a mass movement (only 4 percent of Greeks had supported him before he took power in April 1936). Instead he consolidated his position through collaboration with the monarchy and gross violence against political opponents, several thousand of whom were interned in brutal prison camps. Efforts to establish a fascist-style National Youth Organization were a resounding failure. In Poland, where fascism made no inroads at all, there was a tendency toward an increasingly authoritarian mode of government focused above all on preserving order so as to protect the interests of the traditional elites.

The most undynamic of all the European regimes was that of the stolid António Salazar, prime minister of Portugal from 1932 until 1968, whose “New State” was based on a corporate constitution embodying the values of reactionary Catholicism. States like this were stagnant and oppressive, but precisely because they embodied complex compromises to protect the traditional social order, they were also relatively resistant to extremist experiments.

By contrast, the Soviet Union unleashed a torrent of violence on its own citizens that had no historical precedent, particularly during and after Stalin’s emergence as the unchallenged leader between 1929 and 1934. Close to four million people died in Ukraine during the induced famine of 1932–1933, and about double that number in the Soviet Union as a whole. Stalin was especially ruthless with the personnel of the party that had put him in power. No fewer than 110 out of 139 members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union were executed during the Terror of 1936–1938. Of 1,966 delegates at the 1934 Party Congress, 1,108 were later arrested. The death toll among managers, experts, and scientists was such that the regime’s economic growth came to an end after 1937. The 1937 arrest quota of 250,000 imposed by the NKVD, the Soviet secret police, was exceeded by zealous officers: arrests came close to a million and a half and nearly 700,000 were shot.

Most astonishing of all was the decapitation of the Red Army through the execution of at least 20,000 of its most senior officers, undertaken in the face of the growing threat from Germany and Japan. The killing spree was so intense that Stalin had his own henchman, the odious Nikolai Yezhov, known as the “Iron Hedgehog,” arrested in 1939 and shot the following year. The Georgian dictator, Kershaw reminds us, even “purged” his own parrot by smacking it on the head with his pipe, because he had begun to bridle at its imitations of his hawking and spitting.

Particularly telling are Kershaw’s comparative reflections on the three “dynamic dictatorships.” Whereas Stalin had to show respect for an earlier source of ideological legitimacy, as manifested in his public allegiance to the legacy of Lenin and the tenets of Marxism, Adolf Hitler embodied in his own person the utopian vision of national renewal that had already won over millions of followers when he took power in January 1933. Both regimes achieved an extraordinary hold on collective awareness. The least successful in this respect was, ironically, Fascist Italy, where the term “totalitarian” had first been taken up as a self-description by the leadership.

But even in Italy, the masses were mobilized in support of objectives congenial to the regime. By 1939, almost half of the Italian population was affiliated in some way with a fascist organization. The apotheosis of the leader was official policy. “When you are looking around and don’t know who to turn to any more,” the Corriere della Sera reassured its readers in 1936, “you remember that He is there. Who but He, can help you?” The writer was referring not to God, but to Benito Mussolini. Italians, he went on to say, should write personally to the Duce whenever doubts or difficulties overcame them. “He is the confidant of everyone and, as far as he can, he will help anyone.” Italians appear to have believed this, at least as far as one can tell from the letters (about 1,500 per day) they wrote to him: “I turn to You who does all and can do everything”; “Duce, I venerate you as the Saints should be venerated.”

The outbreak of World War II brought a further scaling up of European cruelty and destructiveness. Kershaw leads the reader into an abyss dimly lit by kabbalistic numbers: 200,000 Germans murdered in “euthanasia” programs; 3.3 million Soviet prisoners of war starved or frozen to death in German POW camps; 400,000 Yugoslavs, most of them Serbs, murdered by the Croatian Ustaša; five and a half million Jews murdered by the Germans and their auxiliaries, of whom 33,771 men, women and children were shot over two days in the Babi Yar ravine near Kiev on September 29 and 30, 1941. Even these stupendous numbers were just a fraction of the total human cost the Nazi leaders had factored into their project of eastern expansion: the original target for the “Final Solution of the Jewish question” was 11 million dead and it was assumed that the “General Plan for the East” would eventually require the “removal” of some 31 million people from the vast German settlement zone.

Even the grotesque body counts of World War I are overshadowed by this descent into apocalyptic violence. And it’s not just the numbers, but the complete collapse of human empathy and the delight in savagery and destruction that mark the final phase of Europe’s second Thirty Years’ War. Kershaw captures the horror in telling details: the lists of executed Jewish children on the meticulously typewritten reports of the Einsatzgruppen; the burning of villages and the slaying of their inhabitants in reprisals from Norway and France to Czechoslovakia, Serbia, Poland, and Russia; the basket of human eyes, freshly cut from captured Serbs, spotted by the Fascist journalist Curzio Malaparte on the office desk of Ante Pavelić, leader of the Croatian Ustaša.

This was the century in which, to borrow the terms proposed by the historian Reinhart Koselleck, the domain of experience exploded the horizons of expectation. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it was the expansion of expectations that caused tumults, forcing the world of experience to accommodate itself to new parameters. But in the twentieth century, the opposite happened: violence and destruction achieved such intensity that they broke the boundaries of the visions that had given rise to them. The values of an old world were left behind before there had been time to replace them. As the Austrian writer Robert Musil put it, referring to the carnage of World War I: “You die for your ideals, because it’s not worth living for them.”

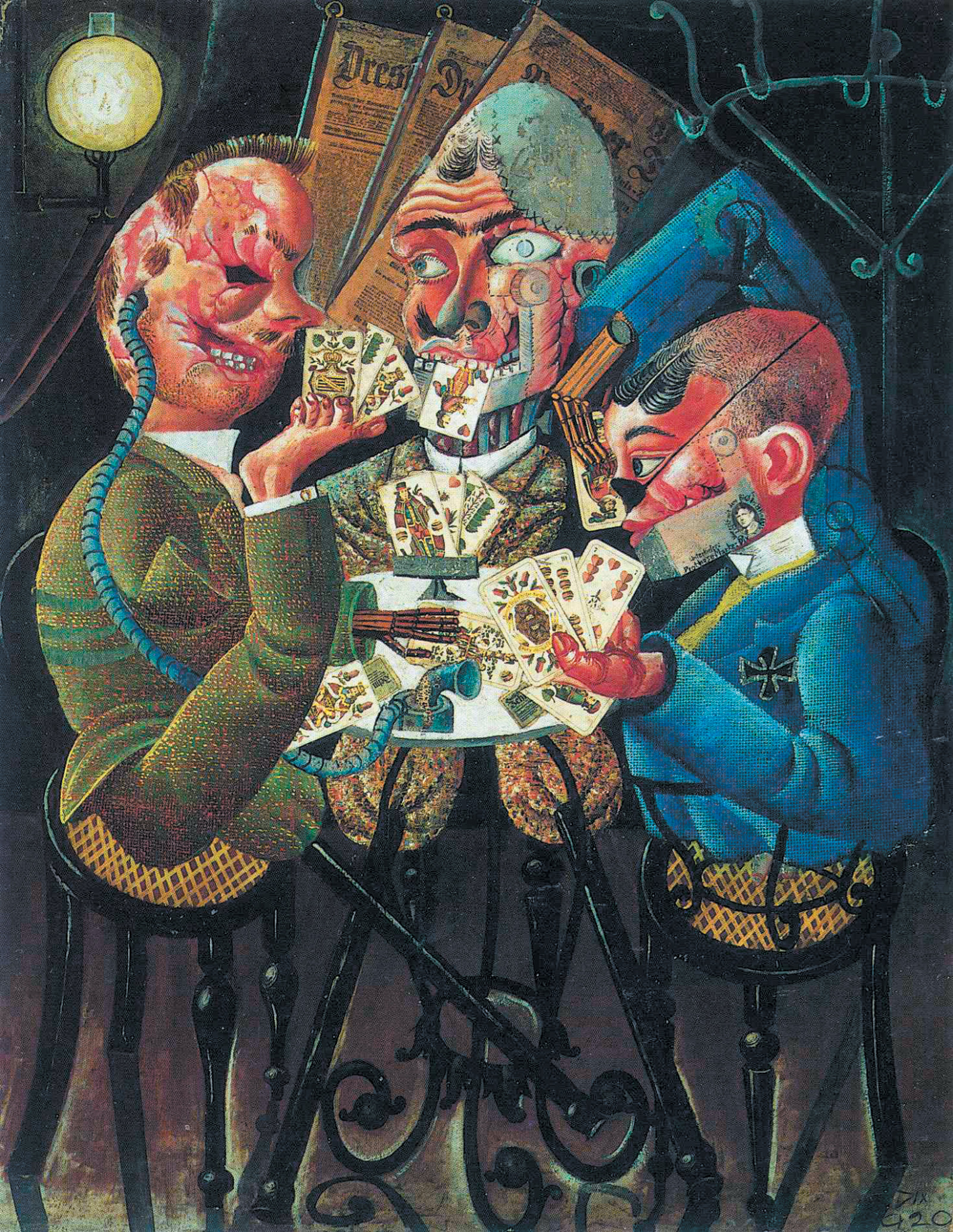

The visual arts are one place where we can track the recurring sense of bafflement and shock at the new contours of modern life: Otto Dix’s The Skat Players depicts a trio of card-playing veteran amputees balanced precariously on chairs, their bodies an agony of disrupted surfaces. George Grosz’s Cheers Noske! shows us an urban street strewn with mutilated bodies, in the middle of which a monocled officer grins and raises a champagne flute, the heel of his boot sinking into the belly of one of the dead. Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, painted to commemorate the three-hour bombardment of a Basque town by German and Italian aircraft in April 1937, evokes the nightmarish violation of private space, in a world sunk, as Picasso himself put it, “in an ocean of pain and death.”

And yet, as the violence reached its midcentury apogee on the killing fields of Central and Eastern Europe, even this gauge seemed to fail. No cultural representations of the Guernica type exist of the mass slaughter in the Ukraine, Belorussia, Poland, and the Balkans. A grainy film of human bodies tumbling like rags from the mouth of a bulldozer speaks more eloquently than any painting could. The immensity of the events beggars our efforts to encompass them.

Kershaw handles the dark materials of his story with extraordinary grace, weaving his themes together with admirable analytical clarity. The central focus of his book is mainly political and geopolitical, but peasants, Christian churches, and popular culture (including Rugby League, Kershaw’s sport of preference) all receive sustained attention. The story of Europe’s second Thirty Years’ War has never been better told, and it is related here in the same sober, humane prose that endeared readers to Kershaw’s prize-winning two-volume study of Adolf Hitler. Other histories of this era have had and doubtless will have more to say about Europe’s global entanglements, about law, the media, social change, and the deepening financial dependency of the European powers on the US, whose ascent to twentieth-century hegemony was accelerated by the conflicts described here. But Kershaw’s account is illuminating precisely because it tightens the focus of the analysis, allowing us to see the continent as a diagram of contending forces, like the storm fronts and wind barbs on a weather map.

In centering the narrative on the Central European terrain that he knows best, moreover, Kershaw exposes a causal force of abiding importance. For it can be argued, without prejudging the vexed issue of “war guilt,” that World War I could not have happened without the emergence of a powerful new German nation-state at the heart of the continent. The Thirty Years’ War of the twentieth century was in part a struggle to address the challenge posed by this inversion of Europe’s traditional geopolitical balance.

By 1949, when this book comes to an end, the problem had been resolved by the truncation and partition of the German state, restoring the heart of the continent to its ancestral condition of weakness and fragmentation. A new kind of German polity then emerged (at least in the West): democratic, pluralistic, peace-loving, oriented toward consensus, and committed to harmony with its neighbors. And even so, twenty-five years after the fall of the iron curtain in 1989, the EU is still struggling to come to terms with the implications of the country’s reunification, not because Germany poses a threat, but because its sheer economic weight and political clout have transformed the inner balance of the Union. The “German question” was a European question in the dark years of the twentieth century, and it remains one today.