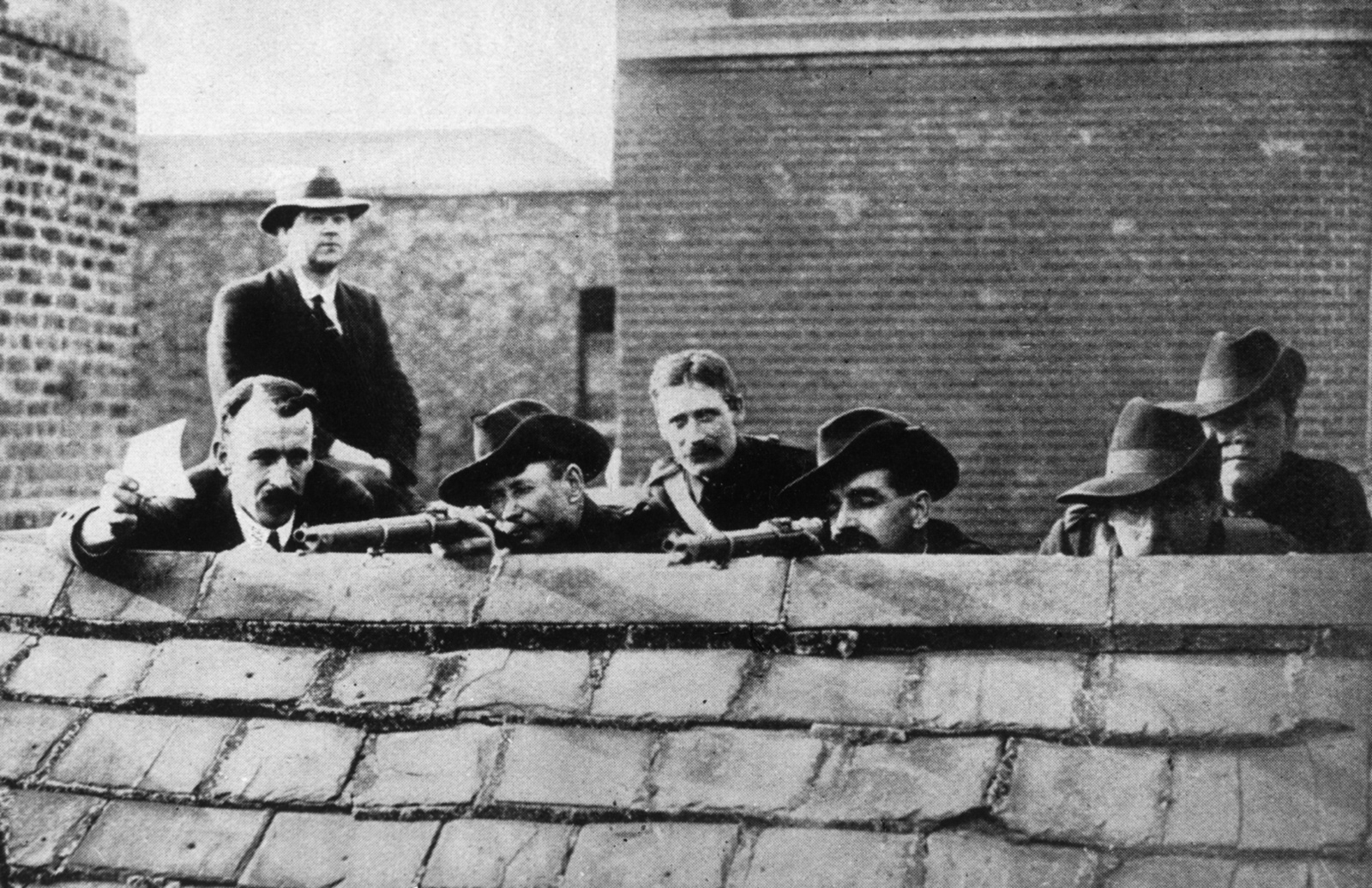

R.F. Foster’s Vivid Faces is a study of the “backgrounds and mentalities of those who made the revolution” in Ireland in 1916. On the morning of Easter Monday, April 24, 1916, members of the Irish Volunteers, a nationalist military organization, and the Citizen Army, a group of trade union volunteers, numbering in all about four hundred, marched into Sackville Street—now O’Connell Street—in Dublin and seized the most notable public building, the General Post Office. Uncertain in number, they were certain in aim: to declare a sovereign Irish republic that was independent of Great Britain. In another part of the city, then allies Éamon de Valera, Éamonn Ceannt, the Countess Markievicz, and other nationalist leaders assembled their troops close to various buildings, such as Boland’s Mills, and took possession of them.

Shortly after noon, Patrick Pearse, in effect the leader of the insurgents, came out of the General Post Office and read a one-page statement, headed (in Irish) “Poblacht na hÉireann,” followed by “The Provisional Government of the Irish Republic to the People of Ireland.” The statement, addressed to “Irishmen and Irishwomen,” began:

In the name of God and of the dead generations from which she receives her old tradition of nationhood, Ireland, through us, summons her children to her flag and strikes for her freedom.

Five brief paragraphs followed. The first called upon the support of Ireland’s “exiled children in America” and “gallant allies in Europe,” these last unnamed but evidently referring to the German government, which was expected in feeble theory to invade Ireland with troops, artillery, and ammunition on behalf of the new Irish government. The second paragraph maintained that “six times during the past three hundred years” the Irish people had asserted, in arms, their right “to national freedom and sovereignty.” Standing on that right, “and again asserting it in arms in the face of the world,” the Provisional Government proclaimed “the Irish Republic as a Sovereign Independent State.”

The third paragraph guaranteed “religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens,” notwithstanding “the differences carefully fostered by an alien Government, which have divided a minority from the majority in the past.” The British government, that is, which had divided Protestants in the north from Catholics throughout the island. Paragraph four: until a permanent national government is established, we “the Provisional Government, hereby constituted, will administer the civil and military affairs of the Republic in trust for the people.” Finally the peroration: the Irish nation must “prove itself worthy of the august destiny to which it is called.” The date, Easter 1916, was carefully chosen, and not only for its Christian emblems. Those who chose it were counting on several facts: the Great War was nineteen months old, “England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity,” and the United States was still in theory neutral.

The proclamation was signed, “on behalf of the Provisional Government,” by Thomas J. Clarke, Seán Mac Diarmada, P.H. Pearse, James Connolly, Thomas MacDonagh, Éamonn Ceannt, and Joseph Plunkett. The passersby to whom Pearse read the proclamation showed no interest in it and were evidently hostile when they heard what it was about.

So the Easter Rising began. The officers of the Crown were taken aback, though the atmosphere in Dublin Castle, the headquarters of the ruling British government, was thick with hints and guesses. The authorities needed a day or two to gather their soldiers and bring a gunboat up the Liffey River, but when the army was directed into the city and started shelling the buildings held by the rebels, the defeat of Pearse and his troops was inevitable. He surrendered, unconditionally, after five days, on Saturday, April 29. According to Foster, during the Rising 450 people, soldiers and civilians, were killed, “2,614 wounded, 9 missing; of those, 116 soldiers had been killed, 368 wounded and 9 missing, along with 16 policemen dead and 29 wounded. Out of 1,558 combatant insurgents, 64 rebels had died.”

Between May 3 and 12, fifteen of the leaders were arrested, court-martialed for high treason, and executed. De Valera was not executed; having been born in America, he was a special case. Sir Roger Casement, who had been knighted for his reports on human rights abuses in Peru and had also investigated conditions in the Congo, was arrested in County Kerry on his return from an abortive mission to gain German support for the insurgents, was brought to England, and hanged in Pentonville Gaol on August 3. Hundreds of men and about seventy-seven women were arrested. Most of the women were released early in May; a few were interned. Constance Markievicz was tried by court-martial and sentenced to death, but her sentence was commuted. The men who were not executed were gradually released over the next year.

Advertisement

As a military exercise, the Rising was a botch. Professor Eoin MacNeill was chief of staff of the Volunteers, but Pearse and Mac Diarmada kept him uninformed of their plans. MacNeill was not opposed, in principle, to a rising, but he insisted that the conditions in favor of such an action were not present in Ireland in April 1916. Pearse’s Rising was supposed to begin on Easter Sunday, but MacNeill, hearing rumor of it, countermanded the decision, and put a notice to that effect in the Sunday Independent. Pearse and his friends decided to ignore him and to call out their troops on Monday morning. They had a fair-sized army at their disposal in Dublin, and some troops in Cork, but in rural Ireland there was chaos.

My uncle, Séamus Ó Neill, had been since boyhood a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, founded in 1858 to work for an independent Irish republic. In April 1916 he was living at home in Clonmel, County Tipperary, and was second-in-command to Sean Treacy in that county. They were ready to rise, and to attack local police stations or military barracks as instructed. But between Pearse’s yes and MacNeill’s no, they were bewildered. Not knowing what to do, they did nothing. Within a few weeks after the Rising in Dublin, my uncle was arrested, consigned to various jails in Ireland, England, and Wales, went on hunger strike in (I think) Frongoch, and was released in the spring of 1917.

His insurgent days were over. He taught at Rockwell College, devoted himself to his first love, the Irish language, and spent a lot of time in Ring, the Irish college in County Waterford, where he met and married the poet Una ni Cuidithe. He took no part in the War of Independence, between 1919 and 1921, or in the Civil War of 1922 and 1923. When the Irish Free State was established in 1922, he joined the police force, the Garda Síochána, was quickly promoted, and enjoyed a long career as Inspector of the Garda in Galway, the district that included the Irish-speaking Aran Islands where the local court conducted its business in Irish.

My uncle is not mentioned in Foster’s book, nor should he be; he was a minor figure. But there must be larger figures of his type, men and women of “the revolutionary generation,” as Foster calls it, who survived but whose insurgency was thwarted, displaced, or turned aside to serve another cause.

Botched as the Rising was, it had a dramatic effect on the attitudes of the ordinary people of Ireland—or the executions had. Something like Pearse’s vision came about: the sacrifice of the holy few transformed the lazy many. Within a short time, even those who were indifferent or hostile to the Rising in April gave their sympathy to the insurgent party Sinn Fein (Ourselves) and turned against the constitutionalists, the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), which advocated that Ireland continue as part of Great Britain, represented in the British Parliament with the aim of being granted Home Rule by the British government. The British threat to impose military conscription on Ireland in early 1918 also did much to turn Irish people against the Empire. In the election of 1918 the IPP was virtually wiped out. Sinn Fein won 73 of the 105 seats. A mystique began to suffuse the memory of the executed leaders of 1916, especially Pearse, which has not disappeared. Yeats wrote in “Sixteen Dead Men”:

You say that we should still the land

Till Germany’s overcome;

But who is there to argue that

Now Pearse is deaf and dumb?

In poems and prose, Pearse, several years before 1916, invoked Christ’s blood sacrifice, his death on the cross, and his resurrection. He was not ashamed to associate those supernal images with his own love of Ireland and the Irish language, along with Ireland’s dead heroes, especially Robert Emmet and Wolfe Tone. In “The Coming Revolution” he wrote: “We may make mistakes in the beginning, and shoot the wrong people; but bloodshed is a cleansing and a sanctifying thing.” Yeats, who knew him well enough, thought him half-crazed, “flirting with the gallows-tree,” but he had a different attitude, too, at least sometimes. The mystique to which I have referred still surrounds Pearse, Connolly, Mac Diarmada, and the other martyrs, despite many efforts by revisionist historians—the School of Irony, as I think of them—to dispel it.

Foster is one of the most persuasive of those historians. Like his mentor, the late F.S.L. Lyons, he evidently thinks that, given a little more time, the IPP would have delivered Home Rule and that it would have been worth waiting for, if only as a step toward eventual sovereignty. But the IPP, with its aim of Home Rule, had already waited a long time. Prime Minister William Gladstone first introduced a Home Rule bill for Ireland in 1886: it was defeated, and defeated again in 1893 by the House of Lords. A third attempt, on January 30, 1913, was defeated by the House of Lords. In 1914 a Home Rule bill was passed, but its application was suspended until the end of the Great War. The Government of Ireland Act, passed on December 23, 1920, excluded six counties of the north—Derry, Antrim, Down, Armagh, Tyrone, and Fermanagh—four of which had secure Unionist majorities. The Northern Unionists, who were allied with the British, at first wanted all nine counties of ancient Ulster, until it was pointed out that in three counties—Donegal, Cavan, and Monaghan—a Unionist majority could not be relied on forever. So the leaders of the Northern Unionists, Edward Carson and later James Craig, settled for six. Partition, as we call it, was enforced. This is where Foster’s reading of a poem by Yeats comes in.

Advertisement

He takes the title of his book from Yeats’s “Easter 1916,” which begins:

I have met them at close of day

Coming with vivid faces

From counter or desk among grey

Eighteenth-century houses.

Yeats goes on to meditate on the transformation of these ordinary men and one distinguished woman, each of them “changed in his turn,/Transformed utterly:/A terrible beauty is born.” I read “A terrible beauty” as Yeats’s phrase for the sublime, that experience of astonishment, terror, dread, and ultimate pleasure that Edmund Burke described in A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757): “Whatever is qualified to cause terror is a foundation capable of the sublime.” Many of the ordinary people of Ireland, I judge, felt a sense of the sublime, even if they never heard of the word, when they thought of the “sixteen dead men,” to refer to another of Yeats’s poems of 1916.

Near the end of “Easter 1916,” Yeats has these lines:

Was it needless death after all?

For England may keep faith

For all that is done and said.

This is often taken to mean: “The Rebels should have been patient, should have given the IPP a bit more time.” But the only faith that England kept—most clearly from February 6, 1912, when Lloyd George and Winston Churchill proposed, in cabinet, to exclude the north from any Home Rule bill, leaving it ultimately under British control—was the inviolable character of Protestant Unionism. That could not be touched. Dublin would have to put up with it. And so it has put up with it from that day until now. The Good Friday Agreement, signed on April 10, 1998, repeated the guarantee in favor of the north, “unless”…but the unless is a fraud since the agreement held that the north would remain separate. It is a fraud unless and until a majority in the north is in favor of joining the south. But such a majority could not happen from here to eternity.

Foster’s aim in Vivid Faces, as I interpret it, is to remove the halo of the sublime from the martyred Pearse and his friends, and to present “the revolutionary generation” as a generation like any other: just like the American, the French, the Russian, Paris in 1968, Berkeley, any rising you care to name. He recognizes that a sense of the sublime is not subject to criticism: there is no point in assuring a victim or an adept of the sublime that he has nothing to fear; he has plenty to fear, to begin with, and he must tense his nerves and feel satisfaction in doing so.

Foster wants to restore the martyrs to the ordinariness from which they came, those men and women with small jobs or minor professions in Dublin; he must undo Yeats’s poem, delete the terrible beauty. That will not be easy, because empirical considerations are likely to be ineffective in such a case. It will not make any difference to John MacBride’s martyrdom if you keep saying that he was a drunk and that he abused Maud Gonne’s daughter Iseult. Yeats knew this, and it made no difference; that is what his poem is about.

Foster is likely to meet a similar difficulty when he says, as he keeps saying in this book, that the Rising was a function of its generation, the youngsters fighting their parents. He first proposed this theme, “the clash of generations,” in his Modern Ireland, 1600–1972 (1988). It is true that John Redmond and the IPP seemed to have been over there in Westminster forever, but Sinn Fein ousted them not because they were old but because they did not do what Charles Stewart Parnell, the head of the IPP, left undone when he died in 1891.

Here I should declare an interest. I have always thought of myself as a nationalist and hoped against hope for a United Ireland in my lifetime. The fact that I lived in a police barracks in Northern Ireland, where my father, a Catholic, was the local police sergeant in a largely Protestant force, probably had something to do with that sentiment. But I now think that partition was inevitable and that it could not now, or in any foreseeable future, be undone. I say this in view of several facts. For example, there was Edward Carson’s speech to fifty thousand Unionists at Craigavon on September 23, 1911, calling on them, in the event of Home Rule passing, to take up the government of the Protestant Province of Ulster.

Then between September 19 and 28, 1912, 237,368 men and 234,046 women signed the Ulster Covenant pledging to use “all means which may be found necessary to defeat the present conspiracy to set up a Home Rule Parliament in Ireland.” King George V opened the Parliament of Northern Ireland (six counties) on June 22, 1921. There was no rational hope of a thirty-two-county republic. I would not protest if Professor Foster were to say “Friend, I told you so.”

On the first page of Vivid Faces he quotes in part, not for the first time in his books, F.S.L. Lyons’s saying of Irish diversity, in his Culture and Anarchy in Ireland, 1890–1939 (1979), that it was “a diversity of ways of life which are deeply embedded in the past and of which the much-advertised political differences are but the outward and visible sign”:

This was the true anarchy that beset the country [in the early twentieth century]. During the period from the fall of Parnell to the death of Yeats [1890–1939], it was not primarily an anarchy of violence in the streets, of contempt for law and order such as to make the island, or any part of it, permanently ungovernable. It was rather an anarchy in the mind and in the heart, an anarchy which forbade not just unity of territories, but also “unity of being,” an anarchy that sprang from the collision within a small and intimate island of seemingly irreconcilable cultures, unable to live together or to live apart, caught inextricably in the web of their tragic history.

Clearly this referred, in 1979, to the violence then raging in the north, the war between Unionist and Nationalist or—there is no merit in avoiding the synonyms—between Protestant and Catholic. But the Easter Rising was a war of the Irish Volunteers and a Citizen Army against the British government. Pearse’s enemy was not Carson or the Unionist north: he had no objection to their arming themselves. The quotation from Lyons, in Vivid Faces, is beside the point. Nor does it make much difference to talk of rival cultures instead of rival ideologies: cultures, too, take to gun and bomb.

Foster’s book is divided into nine chapters, each after the first one called by a verbal noun: Fathers and Children, Learning, Playing, Loving, Writing, Arming, Fighting, Reckoning, and Remembering. The book amounts to a social history, a group portrait, based on the standard records and on materials that have recently been made available in the Bureau of Military History; it is based, too, on a large number of letters, diaries, comings-and-goings.

Multitudes are mentioned, and every individual is pinned down by definitive adjectives, mostly reductive. To name only a few, Daniel Corkery is “a devout cultural nationalist,” Bulmer Hobson “a fervent nationalist and Irish-Irelander,” Pearse “a histrionic and charismatic personality,” Edward Martyn a “Wagnerite and lover of boy choirs.” Also “the tireless Seán MacDermott,” “their ineffective dilettante father Count Plunkett,” “the irrepressible McCartan,” “that seasoned armchair revolutionary Liam de Róiste,” “the inevitable Daniel Corkery,” “the ubiquitous Seán T. O’Kelly,” “the brisk young Ulster extremist Pat McCartan.” The intent of these adjectives is to say: “these men were only ordinary people, not heroes.” A “histrionic and charismatic personality” is just a show-off; charisma is cheap. Foster brings the same verve to his use of the adjective “secular”: it is always a term of praise. He is immensely gifted in making normative usage seem self-evident.

Foster has made good use of amateur witnesses, as I may call them, not warriors but presences. Cesca Trench, Rosamond Jacob, and Máire Comerford have valuable things to report. The most telling portrait is of Alice Milligan:

Pioneer journalist and dramatic impresario, suffered through her Northern connections in the War of Independence; she and her brother (an alcoholic ex-British Army officer) were driven out of their Dublin flat under threats from the IRA in 1921, and she lived out the rest of her long life unhappily in Northern Ireland, caring for relatives, and always in need of money. During the revolutionary period she continued to write poems, in a florid Victorian mode which looked increasingly archaic; publication proved more and more difficult, and she took refuge in various forms of psychic activity, convinced that her gift for divination would help Ireland to evade Partition.

The main difference Foster’s book makes is that, like Senia Paseta’s Before the Revolution: Nationalism, Social Change and Ireland’s Catholic Elite, 1879–1922 (Cork University Press, 1999) and Irish Nationalist Women, 1900–1918 (Cambridge University Press, 2013), it brings women into the group portrait. It is no longer possible to think of the Easter Rising as a revolution of men only, or that the women’s groups called Inghinidhe na hÉireann and Cumann na mBan merely washed the dishes. Some of the women have long been well known—Agnes O’Farrelly, Kathleen Lynn, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, Helena Molony; and some few have been more than names, as we “murmur name upon name”—the Countess, Maud Gonne, Lady Gregory, Iseult. I infer that Foster still thinks that the IPP should have been given more time, even though the version of Home Rule on offer would not have satisfied Pearse and his colleagues. In an endnote, Foster describes it:

The bicameral Irish parliament was not to have power over matters affecting the crown, peace and war, the army and navy, etc., though they would control the police after six years, and could also claim control over matters such as old-age pensions and insurance. There would still be a Lord-Lieutenant, with veto powers, and the imperial parliament retained amendment powers. Revenue, apart from the Post Office, was to be initially managed through the imperial Exchequer.

In 1914 many Irish people would have thanked the British government for that heap of concessions, but not so many after Easter Monday, 1916.