1.

Some years ago, after giving a talk at a college in Louisiana, I was approached at the podium by a middle-aged white man who said, with a genial smile, “Since you mentioned Frederick Douglass, I thought you’d be interested that my family used to own him.” His matter-of-factness was a shock to this Yankee clueless in Dixie. I couldn’t tell if I was meant to congratulate or, perhaps, commiserate, as if his forebears had misplaced some rare collectible. So I said something lame like, “Well, that’s quite something, thanks for letting me know.”

The gentleman identified himself as Mr. Auld, which was, indeed, the surname of the Maryland merchant, Thomas Auld, who, from 1826 to 1846, was Frederick Douglass’s legal owner. Auld inherited the eight-year-old boy from his father-in-law, a slave master named Aaron Anthony, who may also have been Frederick’s father by one of his slaves, Harriet Bailey. Young Frederick Bailey (he took the name Douglass years later, from a swashbuckling character in a poem by Sir Walter Scott) was traded back and forth between the rural household of Thomas and Lucretia Anthony Auld and that of Thomas’s brother Hugh, in Baltimore, where Hugh’s wife, Sophia, instructed the precocious boy in the rudiments of reading. Although Maryland was among the few slave states where teaching literacy to slaves was not illegal, Hugh put a stop to it on the grounds (in Douglass’s recollection) that “if you give a nigger an inch, he will take an ell.” By observing the white children at their lessons, the boy continued his education surreptitiously.

With a reputation for truculence as well as high intelligence, Douglass was treated sometimes as a family servant, sometimes as an adoptive son, and sometimes as a piece of equipment to be rented out for cash. In an incident about which he often spoke and wrote in later life, he fought off a brutal slave breaker named Covey, to whom Thomas Auld had sent him and who tried to beat him for his perceived insolence before retreating in terror from the young man’s fury. In 1836, barely eighteen, Douglass joined a plot to flee to freedom in the North, but when his coconspirators lost their nerve, the plan fell apart.

The Maryland in which Douglass grew up was a state where slavery, by some measures, was in decline. By midcentury, the population of its largest city, Baltimore, exceeded 200,000, of which some 30,000 were free blacks and fewer than 7,000 were slaves. With more and more slaves allowed, by permission from their masters, to keep a portion of their wages when “hired out,” a young man with Douglass’s strength and skills could hope to earn enough someday to buy his freedom.

But the decline in the proportion of slaves was also driven by masters who sold their slaves to cotton planters in the deep South, where “natural increase” in the slave population was insufficient to meet demand. The abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, visiting Baltimore in the 1830s, declared that slave traders should be “sentenced to solitary confinement for life” and sent to “the lowest depths of perdition” in the afterlife. This remark provoked a libel suit, but the selling of slaves continued. Under such circumstances, every time Douglass spoke his mind, or refused an order, or, as in the case of Covey, used his fists, he was risking expulsion to a hell from which few ever returned. It is hard to distinguish decency from self-interest in the fact that Auld did not sell him.

Years later, Douglass wrote about how chronic fear saps the will to imagine a different life:

The people of the north, and free people generally, I think, have less attachment to the places where they are born and brought up, than have the slaves. Their freedom to go and come, to be here and there, as they list, prevents any extravagant attachment to any one particular place, in their case. On the other hand, the slave is a fixture; he has no choice, no goal, no destination; but is pegged down to a single spot, and must take root here, or nowhere. The idea of removal elsewhere, comes, generally, in the shape of a threat, and in punishment of crime. It is, therefore, attended with fear and dread…like [that] of a living man going into the tomb, who, with open eyes, sees himself buried out of sight and hearing of wife, children and friends of kindred tie.

In September 1838 he tried to escape again, and this time he succeeded. Having acquired identification papers from a free black seaman (whether by purchase or as a gift is unclear), he traveled, in sailor’s garb, via train, steamboat, and ferry through Delaware and Pennsylvania to New York City, where he was sheltered by members of what would come to be known as the Underground Railroad.

Advertisement

New York was both a haven and a disappointment. Even “black people in New York were not to be trusted,” he later recalled, and some, “for a few dollars, would betray me into the hands of the slave-catchers.” He stayed long enough to be married—by James Pennington, also a fugitive slave from Maryland, now a Presbyterian minister—to Anna Murray, a free black woman whom he had known in Baltimore, and who journeyed north to join him. Finding it too dangerous to go “on the wharves to work, or to a boarding-house to board,” lest word get out that his capture might yield a reward, he moved with his wife to Massachusetts, where, in the seaport towns of New Bedford and Lynn, he “sawed wood, shoveled coal, dug cellars, moved rubbish…, loaded and unloaded vessels, and scoured their cabins.”

It was his first taste of self-reliance. But Douglass found more than compensated work in “the grand old commonwealth of Massachusetts.” He found his calling. Having begun to “whisper in private, among the white laborers on the wharves…, the truths which burned in my heart,” he ventured, in the spring of 1839, to an antislavery meeting where Garrison spoke, and felt his “heart bounding at every true utterance against the slave system.” Two years later, at the invitation of another member of the abolitionist aristocracy, William C. Coffin, Douglass joined an antislavery gathering on Nantucket, with Garrison again presiding. In the Quaker spirit of that meeting, he rose spontaneously to speak—an event he later described, using the language of religious conversion, as the moment when there “opened upon me a new life—a life for which I had had no preparation.”

His hearers were stunned by his eloquence. “Urgently solicited to become an agent” of the Massachusetts Antislavery Society, he embarked on a speaking tour through New England, upstate New York, and as far west as Ohio and Indiana, where he was “for a time made to forget that my skin was dark and my hair crisped.” Not everyone forgot. Celebrated and gawked at, he was also humiliated and harassed. Aboard ship on the Long Island Sound, he was forced to sleep on the freezing deck. When traveling by railroad, he was “dragged from the cars for the crime of being colored.”

Douglass came to feel that “prejudice against color is stronger north than south.” He felt it even from his sponsors, who, as if coaching a courtroom witness, instructed him to stick to facts and leave interpretation to the experts. “‘Tell your story, Frederick,’ would whisper my revered friend Garrison,” Douglass recalled decades later, investing that word “revered” with something like a sneer. One of Garrison’s deputies, John A. Collins, chimed in with this piece of patronizing advice: “Give us the facts, we will take care of the philosophy.”

It was never an easy task to convey the brute reality of slavery to people for whom it was a faraway abstraction. Slavery still enjoyed a kind of camouflage in a world where, as the historian Greg Grandin has written, “most men and nearly all women lived in some form of unfreedom, tied to one thing or another, to an indenture, an apprentice contract, land rent, a mill, work house or prison, a husband or father.” Even Herman Melville—who detested slavery but also knew other forms of subjection—asked, in Moby-Dick (1851), “Who ain’t a slave? Tell me that.”

Answering this question was a task Douglass accepted with exasperation:

It is common in this country to distinguish every bad thing by the name of slavery. Intemperance is slavery; to be deprived of the right to vote is slavery, says one; to have to work hard is slavery, says another; and I do not know but that if we should let them go on, they would say that to eat when we are hungry, to walk when we desire to have exercise, or to minister to our necessities, or have necessities at all, is slavery.

As a child in Maryland, Douglass may have picked up a New England intonation from white playmates who were trained in elocution by a tutor from Massachusetts. Now “people doubted if I had ever been a slave [because] I did not talk like a slave, look like a slave, nor act like a slave.” But even as his handlers advised him to adopt “a little of the plantation manner of speech,” the words he spoke on stage were being transferred to the page. In 1845, with the publication of The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, he became, as the literary scholar Ross Posnock has put it, “the most famous black exhibit of the nineteenth century.”

Advertisement

2.

Fame, for a fugitive slave, was a dangerous thing. It made Douglass a tempting target for slave catchers, and when friends proposed to arrange “refuge in monarchical England from the dangers of republican slavery,” he accepted the offer. Upon arriving in Scotland, he reported that “it is quite an advantage to be a ‘nigger’ here,” and, lest he not be “black enough for the british taste,” he made a mock promise to keep his “hair as wooly as possible.”

Abroad no less than at home, tension persisted between what his audiences wanted and what he wanted to give them. “Accounts of floggings,” as his biographer William McFeely has written, were among “the most sought-after forms of nineteenth-century pornography (disguised in the plain wrapper of a call to virtuous antislavery action).” Douglass recoiled from this kind of prurience even as he took advantage of it. “I do not wish to dwell at length upon…the physical evils of slavery…. I will not dwell at length upon these cruelties.” In the enlarged version of his memoir, published in 1855 as My Bondage and My Freedom, he wrote that “it was slavery, not its mere incidents—that I hated.” There was, of course, nothing “mere” about the physical abuses he had witnessed and endured, but he bristled with indignation at being regarded as a freak survivor whose capacity for reflection was doubted by some who shuddered and swooned at his afflictions.

He never stopped speaking of “the whip, the chain, the gag, the thumb-screw, the blood-hound, the stocks, and all the other bloody paraphernalia of the slave system.” But as his fame grew, and with it his independence, he became less a scripted witness and more his own man—a man, moreover, of growing political consequence, to whom antislavery activists and, eventually, mainstream politicians turned for advice and for the sheer prestige of his affiliation.

Ironically enough, this enlargement of influence would not have been possible without the Aulds. In November 1846, while Douglass was in Britain, Thomas sold him in absentia, for unclear reasons, to his brother Hugh for $100. Within a month, Hugh accepted an offer of 150 pounds sterling (more than $1,000 in nineteenth-century dollars) from Douglass’s English friends, who had raised the funds to buy his freedom.

When he returned to the United States, he broke with Garrison and did not resume a place in his orbit. (It didn’t help that former allies chastised him for allowing his liberty to be paid for, and thereby, they thought, conceding that it had not been his birthright.) Garrison regarded the Constitution as a pro-slavery document, rejected electoral politics as collusion with a government that countenanced slavery, and favored disunion as the only way to break the unholy bond between the virtuous North and the poisonous South. He also believed that emancipation could be achieved only through “moral suasion”—the conversion of slave owners till they repented of their sin. Doubting the efficacy of these principles, Douglass found himself condemned as an apostate. With the aid of a new patron, the philanthropist Gerrit Smith, he struck out on an editorial and political career of his own. Settling in Rochester, New York, he launched a newspaper, The North Star, as a rival to Garrison’s The Liberator.

In fact, he had never been an acolyte or ideologue. The Mexican War (1846–1848), waged, he thought, on behalf of the Slave Power, and the subsequent Compromise of 1850, which included the Fugitive Slave Law empowering federal agents to return fugitives to their putative owners, turned him toward militancy. Late in the decade he would be implicated as a coconspirator with John Brown, and forced to make a second flight abroad until the danger of arrest had passed. But as he became angrier (“I would not care if, tomorrow, I should hear of the death of every man who engaged in that bloody war in Mexico”), he also became open to building an antislavery coalition by supporting candidates of the new Republican Party (formed in 1854) who hoped to do the grinding work of rewriting the laws until, someday, somehow, slavery would be written out of them.

Three months before the election of 1860, Douglass was still trying to reconcile his radicalism with his pragmatism. He regarded the Republican presidential candidate, Abraham Lincoln, as weak and waffling, but at the same time recognized that Republicans represented the best chance of progress in the struggle against slavery. “Abolitionist though I am, and resolved to cast my vote for an Abolitionist,” he announced, “I sincerely hope for the triumph of that [Republican] party over all the odds and ends of slavery combined against it.”

Douglass’s home in Rochester became at once an antislavery conference center, a station on the Underground Railroad, and a living shrine. Among those who came to pay respects were two women who held what were called “advanced views”—Julia Griffiths, whom Douglass had met in Britain, and Ottilia Ossing, a German Jew of avant-garde temperament—whose devotions were assumed by many to be both intellectual and intimate. His fame (or notoriety) rose to such heights that by the late 1850s Senator Stephen Douglas scored political points by citing Douglass’s relations with white women as a preview of the depravities “Black Republicans” would bring if they attained power.

When they did, in the person of Lincoln, Douglass was initially enraged by the president’s failure to enlarge the sectional conflict from a war to restore the Union into a war to destroy slavery. But in time, as emancipation became an explicit war aim, he became a kind of extramural adviser to the president—meeting with him three times and lobbying him to allow enlistment of blacks in the Union army, to provide them with pay equal to that of their white counterparts, and to retaliate in kind against the Confederacy for its brutal practice of executing captured black soldiers as criminals rather than treating them as prisoners of war. When Lincoln anticipated losing the election of 1864 to George McClellan, who seemed likely to roll back emancipation, he turned to Douglass for help in encouraging slaves in rebel-held territory to flee their masters and join the Union cause. In 1876, at the dedication of the Freedmen’s Memorial in Washington, D.C., Douglass delivered a posthumous tribute to Lincoln that remains among the most eloquent and just appraisals of the man in the vast literature of Lincoln encomia.*

3.

Frederick Douglass was largely successful in ensuring that we would know his life mainly through his own telling. He told it at book length three times: in the Narrative of 1845, ten years later in My Bondage and My Freedom, and most capaciously but also more cautiously, in 1881, in the Life and Times of Frederick Douglas (reissued in a lightly revised edition in 1889). These books recall his transformation from pacifist to militant, and from outsider to insider (he was appointed US minister to Haiti in 1889)—yet all are self-censored records of what the historian David Blight, who is at work on a new life of Douglass, has called a “controlled public man.” As McFeely remarked while working on his own biography, it is rare for “private and sensuous recollections [to] break through the moral he sought to point.”

While we await Blight’s work, two new books have advanced our understanding of the man. Robert Levine’s The Lives of Frederick Douglass, less a life of Douglass than a study of how he told and retold it, delivers nuanced readings not only of the three memoirs, but of numerous lectures, letters, tracts, and Douglass’s sole work of fiction, The Heroic Slave (1853), about the 1842 slave revolt aboard the slave ship Creole, whose leader (“his torn sleeves disclosed arms like polished iron”) seems close enough to self-portraiture to justify Levine’s remark that the novella “has the feel of a play starring Frederick Douglass.”

Levine takes us through Douglass’s conflicting accounts of the Aulds, in which their former slave careens from professions of affection to expressions of rage, and he notes similar oscillation in Douglass’s responses to Lincoln, which begin with suspicion but end, in the last revision of his memoir, “almost as sanitized as a children’s book.” Levine is very good at showing how Douglass modulated the stories he told about his life and times in order to serve his political and personal purpose of the moment.

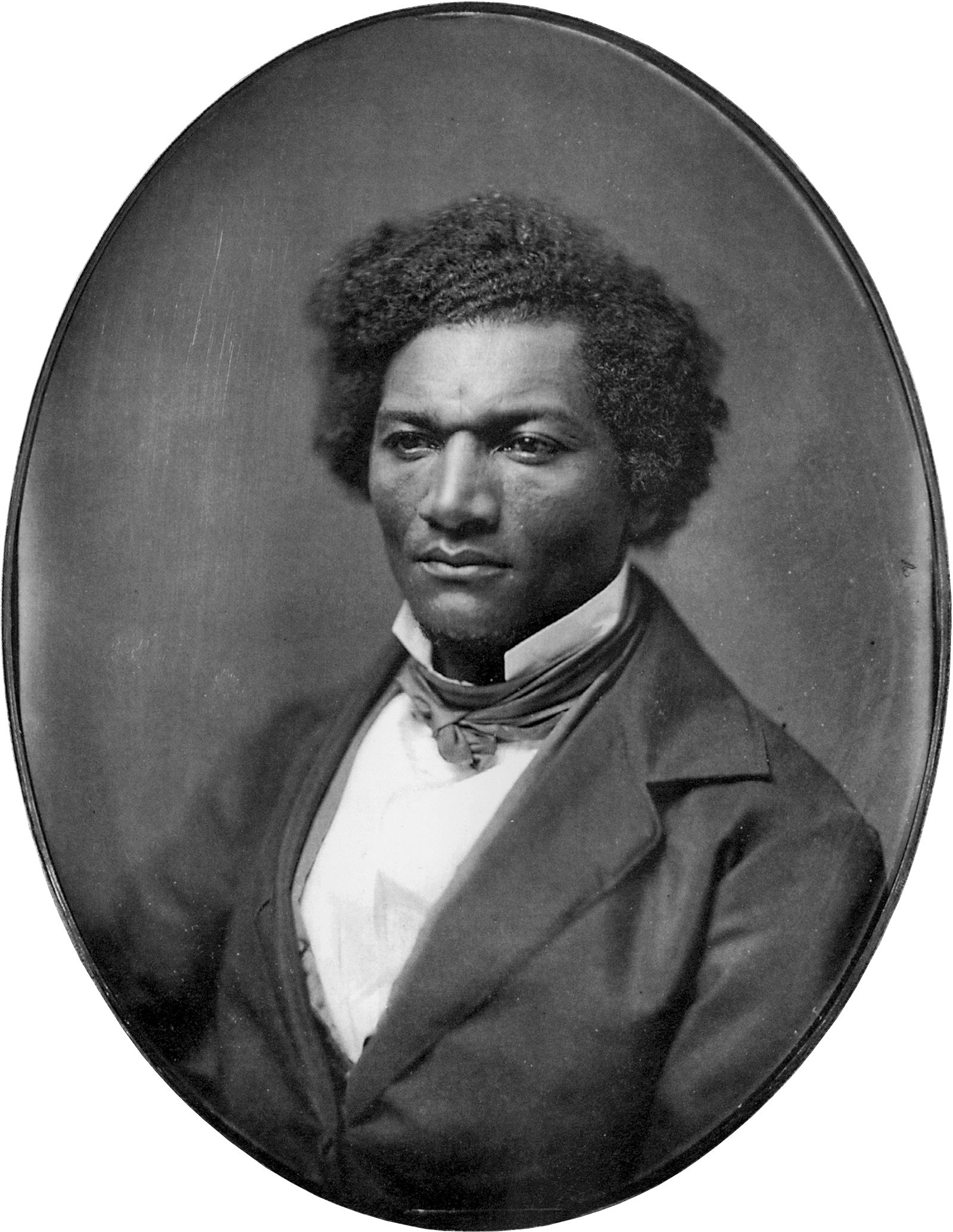

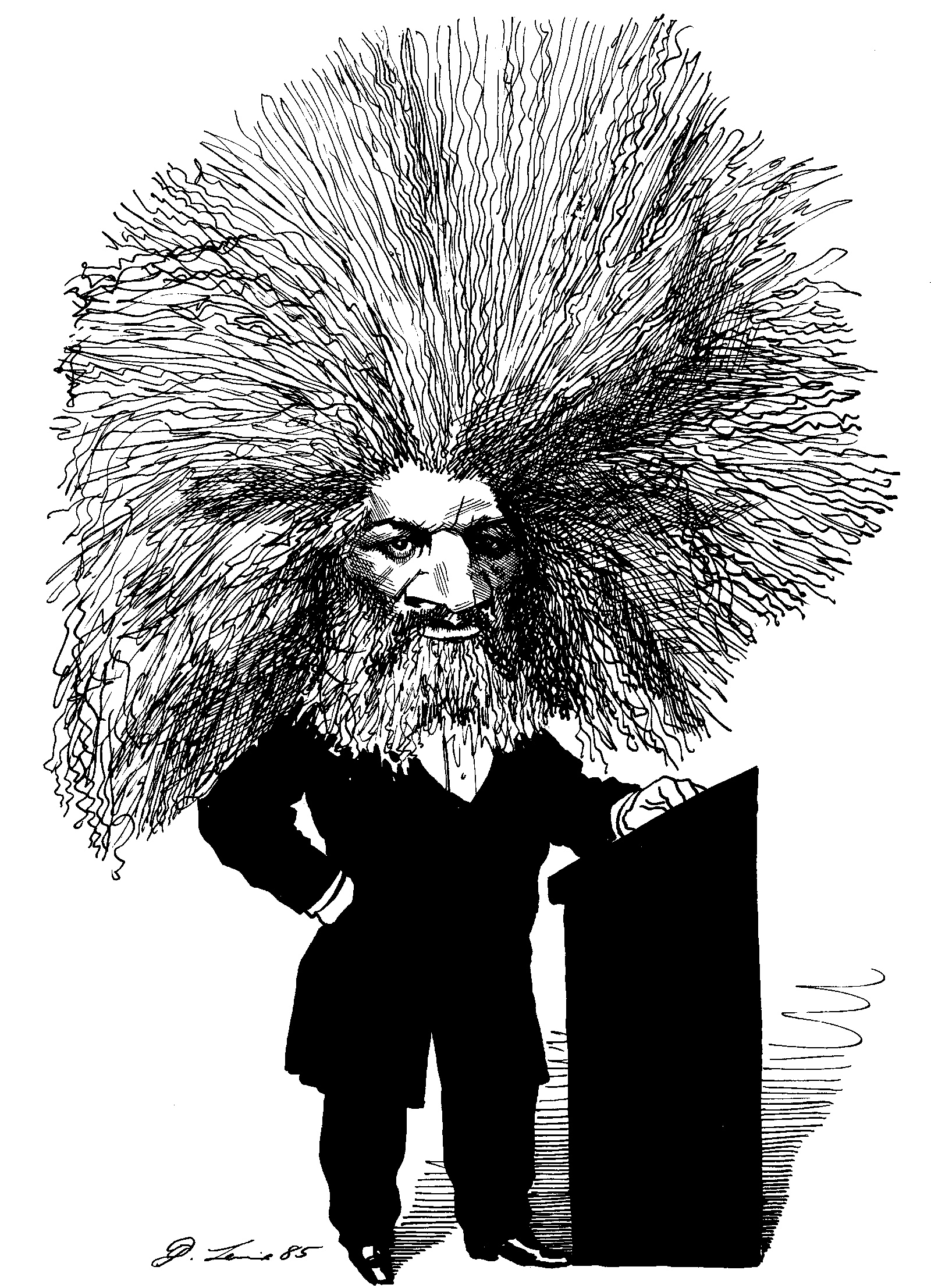

In Picturing Frederick Douglass, John Stauffer, Zoe Trodd, and Celeste-Marie Bernier take us down a less-traveled route into the life. Douglass, we learn, was the most photographed American of his time. Their book serves as a catalogue raisonné of the 160 known photographs, as well as a valuable commentary on the many images derived from them—contemporary cartoons, caricatures, posters, and flyers, as well as posthumous sculptures, stamps, portraits by major artists (Ben Shahn, Romare Bearden), and urban street murals that have current as well as commemorative power.

The authors describe the photographic record as “a kind of visual autobiography,” pointing out, for instance, that during the abolitionist years Douglass tends to gaze straight into the camera with a merciless stare, while in the post–Civil War years he prefers a three-quarter profile, as if he has turned from demanding recognition to assuming it. Especially moving is the transition from images of Douglass as a young man full of constrained fury to the haunting death-bed photograph in which one feels, at last, the surrender of the resistant will.

Another contribution of this book is its inclusion of several of Douglass’s speeches on the subject of photography, in which he had keen interest beyond his experience as a sitter. Its democratizing power greatly impressed him (“the humblest servant girl…may now possess a more perfect likeness of herself than noble ladies…could purchase fifty years ago”), and he hoped it would confer dignity on African-Americans and make them visible not only to white contemporaries but to themselves and to posterity. “Frederick Douglass was in love with photography,” Stauffer and colleagues write, with reason, in the opening sentence of their book. But it was not an unalloyed love. “No man,” he observed in 1862, now “thinks of publishing a book without sending his face to the world with it” in the form of a frontispiece, and “once in the book, whether the picture is like him or not, he must forever after strive to look like the picture.” This was a version of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s lament that “the eyes of others have no other data for computing our orbit than our past acts, and we are loth to disappoint them.” For Douglass, the camera was an instrument of confinement as well as liberation.

Both these books show how carefully Douglass managed his reputation. And so one must look beyond his renditions of himself if we are to glimpse the unmanaged man. This was the man whom one of his British hosts, the Irish Quaker Richard Webb, found “absurdly haughty,” and described, in a strikingly inept phrase, as excessively “self-possessed.” Even his antislavery friends were discomfited by how unapologetically—before and after his legal emancipation—he insisted on owning himself.

Perhaps the closest any writer has come to dispensing with Douglass the monument and imagining Douglass the man is James McBride, in his rollicking 2013 novel, The Good Lord Bird. In that book the central historical figures are Douglass and John Brown. Brown is a cross between Captain Ahab and the boozy gunslinger in Cat Ballou—alternately ferocious and delirious. Douglass is a randy badass. Fooled by a cross-dressing fugitive slave boy into thinking he’s a girl (Henry poses as Henrietta as an escape stratagem), the great man sidles up to him, commencing a slow grope while whispering “my friends call me Fred,” then rising into a speech in which seduction takes the guise of instruction:

They know not you, Henrietta. They know you as property. They know not the spirit inside you that gives you your humanity. They care not about the pounding of your silent and lustful heart, thirsting for freedom; your carnal nature, craving the wide, open spaces that they have procured for themselves. You’re but chattel to them, stolen property, to be squeezed, used, savaged, and occupied.

After this the boy starts to worry:

Well, all that tinkering and squeezing and savaging made me right nervous, ‘specially since he was doing it his own self, squeezing and savaging my arse, working his hand down toward my mechanicals as he spoke the last, with his eyes all dewy, so I hopped to my feet.

Perhaps the fact that a black writer can write about a justly revered black man with such reckless irreverence, in a mode somewhere between slander and affection, is a sign that we may yet get past the squeamish pieties that are another form of the condescension Douglass faced in his own time. He was, after all, not only angry, eloquent, magnetic, and fearless, but also petty, impulsive, and vain—not a piece of personal or collective property but, as even his friends dared to complain, a “self-possessed” man with the low as well as exalted desires that constitute freedom.

-

*

An excellent discussion of Douglass and Lincoln is James Oakes’s The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics (Norton, 2007); see the review in these pages by James M. McPherson, March 29, 2007. For the 1876 oration, see the University of Rochester Frederick Douglass Project, rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/4402. ↩