There are many writers—novelists, critics, journalists—who, after composing and even publishing poetry, come to a halt. Many find notable success in prose: Faulkner, Hemingway, Lawrence of Arabia. There is, however, a sadder version of the story, that of a writer who finds himself unable to continue as a lyric poet: Eliot is the most vexing example. Another, lesser poet, the Tennessean John Crowe Ransom (1888–1974), wrote poetry for only nine years, and spent the rest of his life being a critic (while obsessively revising, mostly for the worse, the poems he had published years before). Like George Herbert, afflicted because he “could not go away, nor persevere,” Ransom could not persevere in poetry; yet he could not retreat from it.

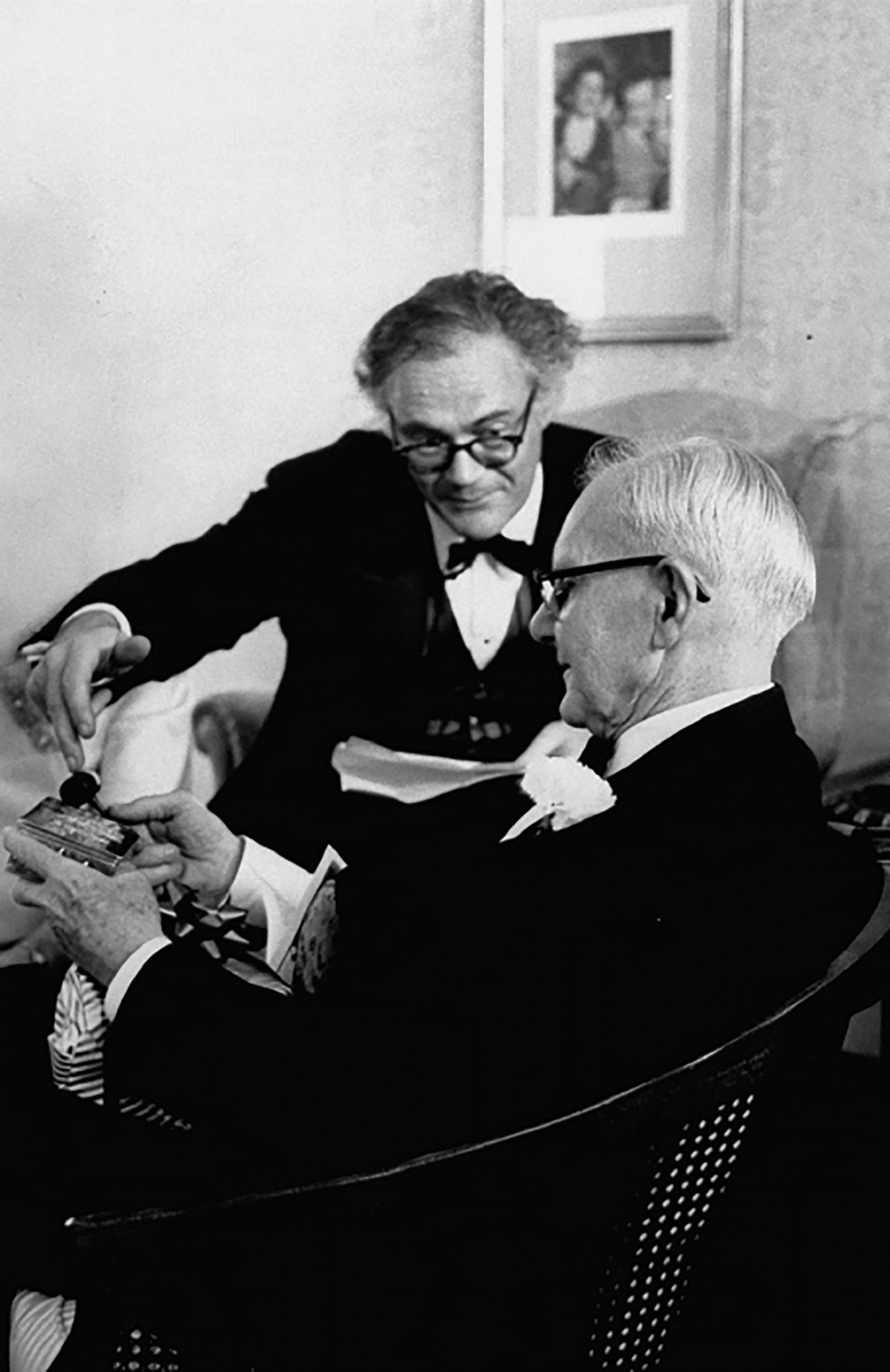

Although the American Academy of Arts and Letters bestowed the Gold Medal for Poetry on Ransom in 1973, the year before he died at eighty-six, he had not written poetry for decades, and as an ironist himself, he would have felt, one imagines, the incongruity of the medal at that moment of decline. Except for his service as an artillery officer at the front in France in World War I, he lived an uneventful life as a son, brother, husband, and father, while conducting a parallel life as a cultural advocate, literary critic, lecturer, teacher, and editor. That he was born a southerner, and a Methodist minister’s son, determined his intellectual and emotional affinities.

After his undergraduate degree in classics at Vanderbilt, his three-year Oxford experience as a Rhodes Scholar, and some high school teaching of Latin and Greek, Ransom was invited back to Vanderbilt as a professor of English. He probably expected to remain in Nashville, but Gordon Chalmers, the president of Kenyon College, pressed Ransom to come to Kenyon and found a literary magazine. In a life-changing move, Ransom at forty-nine went to Ohio and founded and edited for over twenty years the most influential literary journal of its era, The Kenyon Review. With firm taste, high intelligence, and confident literary power, he rounded up a dazzling stable of writers, himself included: Wallace Stevens quipped of the Review, “Why does it exist, if not for the very purpose of enabling Ransom to find himself in its pages?”

Ransom’s own literary criticism argued that since experimental science represents the factual in its universal generality, human beings need, as its complement, imaginative writing aiming at an exact representation of human consciousness and sensibility. If science was the world’s analytic mind, poetry had to be the world’s physical body, manifesting, with logic and precision, the particular nature of sense-phenomena, the feel of the felt world. In The New Criticism (1941), Ransom called for critics who could perceive and describe the high degree of technique and texture by which a poet not only expressed an individual sensibility but also brought to life a recognizable counterpart of the experienced world, making known the feelings necessarily suppressed in the abstract formulations of science.

Ransom’s criticism, dryly witty, is still readable and entertaining (far more so than his generally placid letters). The scant canon of his poetry, less esteemed now than in his own lifetime, will be newly assessed in light of the 380-page variorum Collected Poems, painstakingly edited and well introduced by Ben Mazer. Great poets, whose every word may be significant, require a variorum edition, but Ransom’s poems do not really call out for Mazer’s exhaustive treatment (including annotations, uncollected poems, and every peculiarity of obsessive textual revision). Perhaps to some readers this elaborate edition is justified by Ransom’s achievement; to others it will expose the damaging weaknesses—for so they seem to me—of Ransom’s verse.

In life, Ransom was a generous son to his minister-father and his mother (always in straitened circumstances) and an earnest encourager of his sisters’ education; he was a persuasive teacher, a man of probity, and a sincere and passionate critic. However, some who knew him thought him, however courteous and helpful, fundamentally withdrawn, emotionally inaccessible: a man of “naturally remote and circumspect disposition.” He remained chary of self-exposure even in his criticism, and when he wrote in rhyme and meter (aspects necessary, he thought, to a poem), he was fettered by both his narrow conception of lyric form (which he equated with technique) and by the self-conscious irony of his narratives.

What should we think of a thirty-one-year-old poet who in 1919 puts before the public, as the first stanza in his first book (strangely called Poems About God), these labored and unfunny lines?

In dog-days plowmen quit their toil,

And frog-ponds in the meadow boil,

And grasses on the upland broil,

And all the coiling things uncoil,

And eggs and meats and Christians spoil.

Other early poems exhibit a strange disjunction between title and fable. In one, a farmer, determined to make his every acre flourish, deplores those who would allow space to roses, claiming, before he falls silent, that “nothing is worse than a sniff of rose/In the good strong smell of hay.” Yes, but why is this poem called “One Who Rejected Christ”?

Advertisement

Ransom never reprinted those stumbling poems. In spite of many attempts, he had not yet found a style that fitted his topic. Or, rather, there were too many styles. Among them, we hear Christmas baby talk as a little girl resists her Christian father’s discourse, preferring to think about Santa: she (Ransom wants us to notice) weirdly rhymes “Jesus” with “tease us”:

Father, don’t talk of little Jesus,

You’re only doing it to tease us,

It isn’t nearly time for bed,

And I want to know what Santa said.

Elsewhere in Poems About God we find a spectator scorning the “stinking sweat” of the “thirty fat men of the town” lifting their dumbbells. Yes, but what motive does he ascribe to them?

Dumb-bells left, dumb-bells right,

Swing them hard, grip them tight!

Thirty fat men of the town

Must sweat their filthy paunches down.

Dripping sweat and pumping blood

They try to make themselves like God.

Turn a few pages, and God is talking in a language never heard on earth or heaven:

“For my absolute heaven is high, and nothing dependeth,

Yet it twitcheth my heart, when weeping of women ascendeth.”

What cast of mind generates Ransom’s strange styles and his peculiar versions of conventional genres—allegory, ballad, love lyric, satire?

Ransom’s inner quarrel between the Christian faith of his upbringing (which included Sunday sermons by his father) and a modern rational skepticism is a familiar perplexity in the lives and writings of the Victorians (especially Walter Pater) and of Ransom’s contemporaries (Eliot, Stevens). Ransom’s early revulsion against modern society was complicated not only by his religious sentiments but also by his southern conviction that modern thinking would inevitably bring to the South the industrialism of the commercial North. His nostalgic political conservatism led him, in his forties, to join with friends in a 1930 volume of essays unfortunately called I’ll Take My Stand (a line from “Dixie”: “In Dixie Land, I’ll take my stand”).

The writers saw the (white) agrarian culture of the Old South, with its Protestant gentility and appreciation of leisure, as a heritage too precious to be abandoned. Yet the battle of southern literary intellectuals against modernization—factories, business, naked capitalism—was already lost. Their idyllic picture of staunch Christian farmers, their gentle wives, and their fertile farms left out far too much, notably the black population and its misery. Ransom himself at the time could write equably, “Slavery was a feature monstrous enough in theory, but, more often than not, humane in practice.”

The only contributor who faced “the negro problem” squarely was Robert Penn Warren, arguing that the South’s self-interest absolutely required the economic and vocational betterment of “the negro.” Warren’s tone—thoughtful and sociological—suggested that behind his appeal to white self-interest lay a philosophical argument envisaging the absolute right of the negro to educational access and to opportunity in labor.

Ransom, at seventy, turned a self-critical eye on his time as an agrarian:

I was once a member of a group of young men in Tennessee who made a public diversion in favor of an agrarian way of life which was fast becoming outmoded, even in that happy region. And I recall how it was a commonplace in our observation that it was always the woman of the house who made her husband sell the farm and move to the city, where her own drudgery would be lightened, and her children could go to proper school; we never found the right words to address to the woman.

That “group of young men” created a journal, The Fugitive, which, though it was short-lived (1922–1925), offered them companionship and a place to publish their poems. The young Fugitives evolved into the middle-aged Agrarians of I’ll Take My Stand, but Ransom soon turned back from economics to literature.

Throughout his nine short years of writing verse, Ransom persisted in his quarrel with God. In his second volume, Chills and Fever (1924), he first exhibited his characteristic manner, one conveying grief at a rather chilly distance (the reader is expected to see through the irony). The closing stanza of the frequently anthologized “Bells for John Whiteside’s Daughter” is spoken as the mourners of the young girl prepare to leave the house, where they have viewed her in her open coffin:

But now go the bells, and we are ready,

In one house we are sternly stopped

To say we are vexed at her brown study,

Lying so primly propped.

I have never so disliked the coercion of rhyme and alliteration: “sternly stopped” and “primly propped” (“propped” in a coffin? “sternly stopped” by whom? And by whose “primness” is she thus “propped?”). The arch old-fashioned metaphor “her brown study,” placed as a deliberately chilly euphemism for death, fails to convince.

Advertisement

Another of Ransom’s middle modes is the faux-medieval. In “Fall of Leaf,” two lovers with banal modern names, Dick and Dorothy, ponder whether they should leave their love in the woods for religion’s “slim white spire.” Dorothy and Dick speak in alternation—but what they say is hardly credible as modern verse:

“Dick, those are the Holy Rood

And sweet Saint Margaret’s sisterhood.

Fearful are the maids, nor many,

Narrow is their bed;

They must open not to any

Woodwife wrapped in red.”…“Dick, they tend Saint Gregory’s tomb,

The strictest monks in Christendom.

Tenants of a godly house,

Of cleanly gear and hallowed,

They will think but little use

Of woodman stained and yellowed.”

Other modern poets, notably Yeats, have put on medieval garb, following in the tradition of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s “The Blessed Damozel,” but they have not inserted into their stanzas, like stones in a pudding, a Dick and a Dorothy. The glance back at the Middle Ages rose to fashion among the Romantics, in gothic tales such as Coleridge’s “Christabel” and Keats’s “La Belle Dame Sans Merci,” but in those works the fiction of the archaic was sustained. Only in the fin de siècle did the fiction become self-consciously staged: in Rossetti’s painting The Annunciation, the apprehensive virgin is a modern girl in a shift, but the biblical adaptation is still coherent in aesthetic tone. Ransom would have named the virgin Mabel, not Mary: he writes to puncture the religious fiction while still wanting to keep it alive.

Ransom’s cartoon self-portrait in “The Vagrant” as a medieval village idiot expects us to translate the portrayal into favorable terms. The vagrant, scorning the country maidens (with contemporary names), forswears their “sweet bites for red lips” in favor of imagined literary ladies:

With a knot in his bosom

And a bee in his brains,

He goes full of pictures

Around the flat lanes….Lou Margaret, Kittie,

Em with the country curls,

Are sweet bites for red lips,

Very fine girls;With the Queen Guinevere,

Troy’s women, Eden’s,

Towns not near.

“So leave him leering,/Loitering in the lanes,” says the speaker in his jaunty dimeter: “There’s no mischief in him/But a bee in his brains.” The coyness here reshapes “a bat in his belfry” to “a bee in his brains,” and expects congratulation for its wit.

Ransom finds yet another way to guarantee distance from his poem’s own narrative: closing a romantic encounter with ironic bathos. In “April Treason” a painter is drawn by sexual passion to destroy his painting, even “trampl[ing] it with loathing.” After kissing his beloved, the painter walks home, straight into bathos:

Then a silence straightway took them

And they paced the woodland homeward.

What a bitter noon in April

(It was April, it was April)

As she touched his fleeting fingers cold as ice

And recited, “It was nice!”

What is one to make of this meager vapidity as a finale to the painter’s treason to his art? Tinkering with his prosody, here as elsewhere, Ransom tries lines of four, five, and three beats, but achieves none of the architectural firmness of comparable stanza variants in Yeats or Auden. Ransom was praised for his “irony,” for his “dualism,” but there has not been much inquiry into the ultimate poetic value of the repetitive fashion by which he creates a situation and then flings graffiti on it.

Many things, in Ransom, come to spoil romance: in “Good Ships” (an almost-Petrarchan sonnet), a couple who had fallen in love at “one of Mrs. Grundy’s Tuesday teas” but were afraid to pursue the affair are compared to ships that pass in the night and exchange only conventional “nautical technicalities.” For this evasion of their erotic potential, the lovers are metamorphosed into commercial ugliness:

Beautiful timbers fit for storm and sport

And unto miserly merchant hulks converted.

Ransom’s morose conviction that (as Stevens put it) “fault falls out on everything” exists in an unconvincing intellectual space neither tragic nor comic nor truly ironic. The conviction cannot convince because it arrives always accompanied by an ironic gust of wind taking back all that was given. And there it ends. What comes after irony? Nothing; the imagination has been poisoned. In true irony, the poem must continue beyond the simple abandonment of a blighted idealism; see, for instance, Yeats’s ironic closing questions casting the initial premises of a poem into doubt: “Was there another Troy for her to burn?”; “Did she put on his knowledge with his power…?” Ransom is not inclined to second-guess his disappointments.

The attempt to stage aftermath can sometimes expire in weariness. In Ransom’s sardonic version of the apocalyptic encounter of Christ and Antichrist in the battle of Armageddon, Christ exchanges his “dusty cassock” for dress identical to Satan’s, and succumbs to the ministrations of the “perruquiers” (wigmakers) of the Antichrist’s pavilion, who dress his hair (“his thick chevelure”) and scent his beard. The central stanza of Ransom’s “Armageddon” preposterously harmonizes—with ostentatious rhymes—the Antichrist’s poetic art of sensual “dithyramb” with the “holy paternoster” of Christ the Lamb:

And so the Wolf said Brother to the Lamb,

The True Heir keeping with the poor Impostor,

The rubric and the holy paternoster

Were jangled strangely with the dithyramb.

This “new brotherhood” in which the Antichrist and Christ sit “like twins at food” collapses under the withering eye of a Christian elder, and Christ decides to resume battle with the forces of evil. The Christian myth-devolved-into-farce comes to an end—as we now routinely expect in Ransom—in anticlimax, as Satan the petulant Adversary says he’s tired of Armageddons:

The immortal Adversary shook his head:

If now they fought too long, then he would famish;

And if much blood was shed, why, he was squeamish:

“These Armageddons weary me much,” he said.

If these fanciful heavy-handed torsions of the biblical story pleased in 1924, they seem to me now to have lost their savor.

In 1963, when he was seventy-five, Ransom commented retrospectively on his own themes, insisting on “the parity of the two sides,” the impulses to evil and the impulses to good:

The man who limits himself, aspiring to pure goodness or saintliness, seems to us very far from possessing that entire vitality which Providence has meant for him. He has not elected the whole joy of life.

Yet it is not any impression of “the whole joy of life” that appears in Ransom’s overwrought manipulations of Christianity, but rather the grimacing spasm of the deathbed, followed by a fiercely whimsical shrug.

Ransom admired Hardy’s uneven meters, but when—as in “Here Lies a Lady”—he sets the hic jacet of the tombstone in a waltz rhythm, it is hard to see what he gains by his tripping anapests and dactyls:

Here lies a lady of beauty and high degree.

Of chills and fever she died, of fever and chills,

The delight of her husband, her aunt, an infant of three,

And of medicos marveling sweetly on her ills.

Even the seriousness of the final stanza is marred, it seems to me, by Ransom’s posed reprise of her fever and chills:

But was she not lucky? In flowers and lace and mourning,

In love and great honor we bade God rest her soul

After six little spaces of chill, and six of burning.

It is certain that Ransom thought he had made something beautiful in texture by his waltz: But can it be ratified by a contemporary reader?

By his third and final volume of poems, Two Gentlemen in Bonds (1927), Ransom had quelled to some extent his obstreperous compulsion to vandalize the serious, to blaspheme against Christ, to waltz at tombs—and then to undo it all by a self-exculpating irony. Nonetheless, the curious notion that the medieval is a humorous façade for the modern still organizes the subtitle of part of the book, “A Tale in Twenty Sonnets,” in which we meet two “notorious brothers” (the titular “gentlemen in bonds”), Paul a sensualist, Abbot an ascetic. Paul lusts after their innocent cousin, Edith, dwelling with them in their castle, and Ransom’s stiffly uncertain tale goes overboard in describing Paul’s rape of Edith:

She was small, ripe, round, a maid not maculate

Saving her bright cheeks, but the rude bridegroom

Claims her, his heavy hand has led her home.

Nor did he pull her gently through his gate

As had a lover dainty and delicate:

The two-and-thirty cut-throats doing his will

Tore off her robe and stripped her bare until

Drunken with appetite, he devoured and ate.

Ransom mocks his quasi-Petrarchan tale-in-sonnets by ascribing a Petrarchan taste to the gaunt monkish brother named Abbot: “The man could talk in Latin, music, mime,/Or sonneteer with Petrarch in his prime,” yet “He waved his black sleeves like an evil prophet,/Death in his every verse or not far off it.” (Polonius lurks: we hear him saying of the rhyme “prophet” and “off it,” “that’s an ill phrase, a vile phrase.”) The Manichaean brothers, and the rape of Edith, are means by which Ransom can sketch a base sensuality and a death-obsessed poetry, but the reductive scheme vitiates any human implication. If the twenty-sonnet narrative is an allegory, it has nothing to allude to; if a parable, it is too voluble.

The medievalism is notably diminished in Ransom’s famous poem “The Equilibrists,” which, although entirely indebted to Donne, finds its own originality within that “metaphysical” tradition. The speaker exposes the predicament of intense lovers who, observing Honor, continue their lives without yielding to forbidden sensuality:

At length I saw these lovers fully were come

Into their torture of equilibrium;

Dreadfully had forsworn each other, and yet

They were bound each to each, and they did not forget.

Although the poem rehearses once again the Manichaean division of the ascetic from the sensual, and borrows from Dante’s pictures of hell the lovers’ incessant repetition of their sin, Ransom manages better than elsewhere the infiltration of the violent into the chaste. The narrator addresses the tortured lovers:

Would you ascend to Heaven and bodiless dwell?

Or take your bodies honorless to Hell?…

Great lovers lie in Hell, the stubborn ones

Infatuate of the flesh upon the bones;

Stuprate, they rend each other when they kiss,

The pieces kiss again, no end to this.

As they refuse both chaste Heaven and a place in Hell, the lovers-in-equilibrium are exalted by their pain into two burning stars. Remembering Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,” Ransom allows the narrator to compose an epitaph for the Equilibrists, inscribed on their shared grave:

But still I watched them spinning, orbited nice.

Their flames were not more radiant than their ice.

I dug in the quiet earth and wrought the tomb

And made these lines to memorize their doom:—

Epitaph

Equilibrists lie here; stranger, tread light;

Close, but untouching in each other’s sight;

Mouldered the lips and ashy the tall skull,

Let them lie perilous and beautiful.

The stately quatrains fit the stately Platonic lovers, and the classical epitaph brings Ransom back to his undergraduate study of Latin and Greek. Ransom’s discretion prevents any tethering of “The Equilibrists” to events in his own life. Still, for all its mannered stance, the poem remains human and unmocked.

Poetry was dear enough to Ransom for him to devote the rest of his long life to it, whether in writing essays, soliciting and choosing material for The Kenyon Review, or tirelessly giving lectures. It is often forgotten that the “New Criticism” assumed that its practitioners or theorists would know several languages, and would have read enough history and biography to prepare their minds to think about poetry. The New Critics whom Ransom summoned were to bring to their accounts of poetry all the sophistication that historical or biographical critics possessed, but they were to step further into the footprints of the poem than those academics—the majority—who stopped at a moral or academic commentary.

The New Critics who responded to Ransom’s call—Tate, Jarrell, Blackmur—had all begun as poets, and knew intimately what it was to shape a line or a stanza, to create a rhythm or a form of closure. They were evangelists of poetry, wanting others to see a poem not as a moral essay or a historical illustration but as the creation of a set of ravishing lines produced by a long discipline of study, training, and reflection. The cognitive value of poetry, for Ransom, lay in its recreation, in symbolic form, of the phenomenology of the world’s body, an irreplaceable process if human beings were to recognize themselves in their felt world.