For most of the past 135 years, the central theme of Afghan history has been not outside interventions in Afghanistan—crucially important though these have been—but the attempts by Afghans themselves to create an effective modern state. Recent works by Robert D. Crews and Nile Green bring out the extent of this concern among large sections of the Afghan elites. On the other hand, the works of Antonio Giustozzi illustrate the immense obstacles that such efforts have faced, both from the resistance of much of the population and from central and enduring features of the Afghan state itself—features that it has shared with many other states in the “developing world,” and indeed in late medieval and early modern Europe.

Today, with most US and NATO troops withdrawn, the modern state in Afghanistan is once again fighting for its life, not only against a range of Islamist forces, but against its own inner demons. So far, its prospects do not look good. Twice since late September important towns have fallen to the Taliban and have only been recovered with the help of US air power and special forces. All but a small part of the state budget is supported by Western aid, with the US wholly responsible for funding the armed forces.

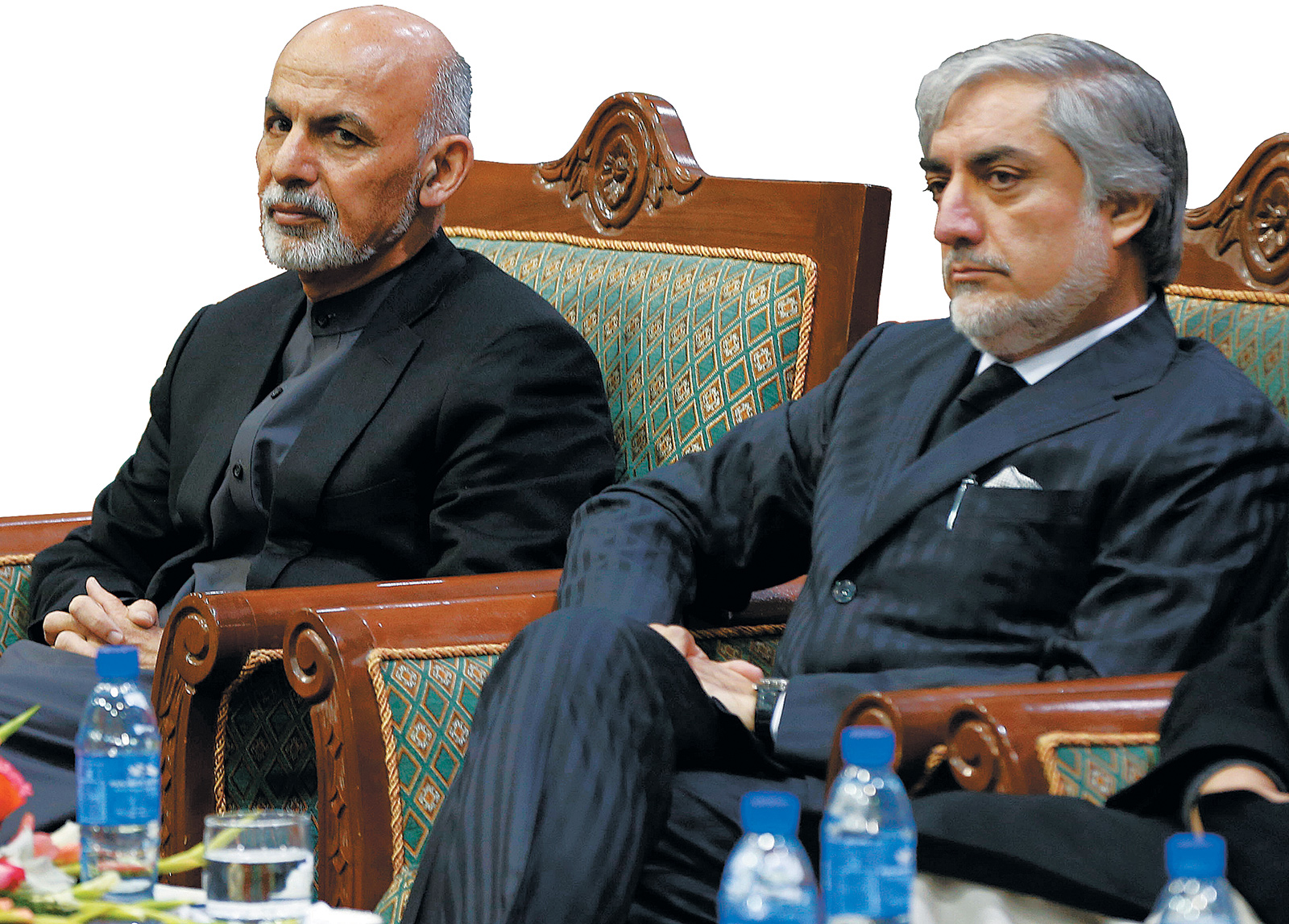

The chances of the state surviving without such US support appear minimal. Equally importantly, as I found during visits to Afghanistan in June and December of last year, the dual government jointly run by President Ashraf Ghani and Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah is largely paralyzed by its internal divisions. The arrangement between the two men was brokered by the US in 2014 as a way of resolving the bitter dispute between them over the presidential election that year, which Abdullah’s followers believe was rigged against him. It never seemed likely to produce effective government—and it hasn’t.

The split between Ghani and Abdullah reflects in part that between the ethnic Pashtuns (the old dominant nationality of Afghanistan, with roughly 45 percent of the population) and the next-largest ethnic group, the Tajiks, who make up about 25 percent. This split has shaped much of Afghanistan’s modern history, with the Taliban attracting support from Pashtuns in part because of resentment at perceived Tajik domination since 2001.

Afghanistan, however, is divided along many other lines, which often crisscross one another in highly confusing ways: between the other ethnicities of the country, including Hazaras and Uzbeks; between various regional warlords, such as Vice President General Rashid Dostum, the leader of the Uzbeks; Atta Mohammed of the northern Tajiks; and Ismail Khan in Herat. In the Pashtun areas, there are conflicts among the Pashtun tribes. There is a deep and long-standing division between the relatively liberal world of the educated classes in Kabul and the deeply conservative countryside.

The paralysis of the government is undermining the Afghan state’s ability to wage war successfully against the Taliban. According to the US special inspector general for Afghan reconstruction (SIGAR), the Taliban today control more territory than ever before. This is the case despite between $4 and $5 million of annual US military aid and financing, an army that, on paper, outnumbers the Taliban several times over, and the continued presence of US special forces and air power. The threat of sweeping Taliban military successes led the Pentagon successfully to pressure President Obama to cancel the planned full US military withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2015.

Now—as articulated by the outgoing US commander in Afghanistan, General John Campbell, and by General Joseph Dunford, the chairman of the Joints Chiefs of Staff—the Pentagon is pushing President Obama to abandon his plan to halve the existing force of 9,800 by the time he leaves office. General Campbell warned Congress in February that the Afghan armed forces will not be able to stand alone until the 2020s, and that unless the US adjusts its present strategy, “2016 is at risk of being no better, and possibly worse, than 2015.” He would have been more accurate if he said “definitely worse.” In fact, absent a peace settlement, it looks as if the US military presence will have to be indefinite.

The present condition of the Afghan government also makes it very difficult for its leaders to come up with a peace offer that the Taliban could accept even as the start of a serious negotiating process; and such a process would in all circumstances be appallingly difficult. A peace settlement would require at least partially overcoming the tensions that have tormented Afghanistan since the inception of the modern state in the 1880s. These include tensions between the state and forces of regionalism and tribalism; between state-led modern institutions such as schools and religious institutions and the opposition of social conservatives; between the cities and the countryside; and among Afghanistan’s different ethnic groups.

Advertisement

At the heart of the Afghan experience—as that of so many other societies in the modern and early modern worlds—has been what Ernst Bloch called “the simultaneity of the nonsimultaneous” (die Gleichzeitigkeit des Ungleichzeitigen): the coexistence within the same society of archaic patterns of culture and social organization with other elements that are entirely part of new regional and even global developments.

Robert Crews’s extremely valuable and interesting work Afghan Modern: The History of a Global Nation focuses on the second part of this combination. As he eloquently describes, at the heart of Afghanistan’s connections to the wider world have been trade, pilgrimage and study, and migration. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,

Afghan Muslims traveled far and wide within the country and beyond its borders to seek religious guidance, but, as in earlier periods, commerce was the primary Afghan gateway to the world.

Until the sixteenth century CE, Afghanistan had straddled one of the great trade routes of the world, linking South Asia with the Middle East, Central Asia, and, beyond them, Europe and China. These routes, however, declined radically in importance as a result of the transfer of so much of Eurasian trade to European-controlled maritime routes.

Afghanistan today possesses many of the institutions of a modern state—including a centralized administration, a bureaucracy, a regular army, and a uniform state judicial system—but in practice it is incapable of extending real administration to most of its own territory, or of keeping its own followers loyal to the state rather than to other centers of power. Lacking an ability to register and administer most of the population, Afghanistan, like other early modern states, has always tended to depend on the taxation of trade rather than agricultural production for its revenue. So apart from impoverishing Afghanistan’s cities, the loss of much of this trade has also meant that Afghan governments have never been able to raise enough domestic revenue to cover their basic needs.

Unlike the fertile plains of north India, arid and mountainous Afghanistan has also not produced enough agricultural surplus to support effective governments—which helps explain why until the collapse of the Mughal and Safavid empires in the early eighteenth century CE, the lands of what we now know as Afghanistan were usually loosely ruled by empires based in India, Iran, or Central Asia. In recent times, Afghanistan has notoriously produced one agricultural product much in demand on international markets, and at the highest prices: the opium poppy and its derivative, heroin. This trade has integrated Afghan businessmen (and also politicians, warlords, and the Taliban) into international criminal networks spanning the entire globe.

I vividly remember in the winter of 1988–1989, on a journey with the Afghan Mujahideen, staying the night at the compound of a local chieftain in a village south of Kandahar. In the early morning, I staggered out to relieve myself (keeping carefully in mind the strict instructions I had received the previous night about the location of the women’s quarters, which of course were to be strictly avoided). The scene that met my eyes was at first sight the classical one of an archaic, unchanging, and isolated Afghanistan, with its mud houses, camels, and rigid codes of honor. And certainly—apart from their weapons—the appearance and behavior of the Mujahideen with whom I was traveling did nothing to belie such an image.

However, in one corner of the compound was something very large, covered with a tarpaulin and with a young goat lying on top. Thinking that this might be some interesting piece of captured Soviet weaponry, I lifted a corner of the tarpaulin and discovered a brand-new, lovingly cleaned Mercedes truck. I asked the village chief about this. “Bought with my own money,” he boasted proudly. “Oh, and how did you earn the money?” I asked. Looking me very straight in the eye, he replied, “Sheep!” He then asked for my signature to endorse his visa application to visit the United Kingdom, “on business.”

Given that the heroin trade has been estimated to account for up to two fifths of the real (as opposed to recorded) Afghan economy, if it could be legalized and taxed, this alone would largely solve the Afghan state’s lack of revenue. There is, however, no chance of other countries agreeing to this; and in consequence, while heroin certainly contributes to the well-being of many Afghans (as well as harming others), it is a threat to the state. This is not only because it helps finance the Taliban insurgency, but because even among the forces that support the state, the money from opium poppies is by its very nature a decentralizing force, distributing power to the warlords and militias that control the trade.

Advertisement

The inability to raise domestic revenue has always left the Afghan government fatally dependent on sources of income from outside its borders. The initial basis of the modern Afghan state in the 1880s could not have been created by Afghan leader Emir Abdur Rahman without British arms and financial subsidies, provided in order to build up Afghanistan as a buffer against the Russian Empire. During the cold war, dependence on US and Soviet aid was to have the most catastrophic consequences for Afghanistan.

A central purpose of Afghan History Through Afghan Eyes, the fascinating collection of historiographical essays edited by Nile Green (following his previous edited volume Afghanistan in Ink: Literature Between Diaspora and Nation, 2012), is to counter what he calls the “Great Game paradigm,” which “places at the epicenter of historical causation external agents and imperial foes, foreign soldiers and domestic rebels.” I have a great deal of sympathy for this critique.

In the years immediately after the US takeover in 2001, many of the hordes of Western advisers, aid workers, and officials who descended on the place did seem to believe that the views of the US Congress mattered more to Afghanistan than those of its own people. However, I would have to qualify Green’s critique by pointing out that it was and is Western states that have paid to rebuild and maintain the contemporary Afghan state.

This issue is related to a wider problem in the work both of Crews and of Green and his contributors: they fail to address adequately the deficiencies of the modern Afghan state and institutions in general. Both books are at pains to stress the vitality and centrality of the modern features of Afghanistan over the past century—for example, the growth of a small but vibrant intelligentsia with a strong sense of Afghan nationalism, and of a state committed in principle to modern development—and to counter what they see as false stereotypes of isolation and conservatism. Crews strongly evokes the scope and activities of the Afghan diaspora extending from South Africa to California. But while their works are very valuable in themselves, they also in certain crucial respects rather miss the point.

Crews gives a generally convincing though sometimes overdrawn picture of the progress of modern change in Afghanistan in the course of the twentieth century, especially in the three decades between World War II and the Communist coup d’état of 1978. During this period, the governments of King Zahir Shah and his prime minister Sardar Daud Khan (who deposed him in 1973) made real if limited efforts to modernize the country through the spread of education (including for girls) and infrastructural development, like the giant US hydroelectric and irrigation project on the Helmand River, which is still not working despite efforts to revive it. This picture of modernization, moreover, is chiefly urban. The Afghan countryside is rarely mentioned by Crews, even though in the 1970s the proportion of the Afghan population living in the countryside may have been as high as 87 percent. At the end of the royal era, illiteracy levels in the countryside remained among the highest in the world, and a large majority of the rural population had no access to health care, electricity, or paved roads.

It is also true that the period from the 1940s to the 1970s saw a strong growth of state administrative and police presence in the Afghan countryside. Since, however, these officials and policemen were all too often both deeply corrupt and extremely brutal, the result was rarely to consolidate the loyalty of the local population to the state. Meanwhile, the growth of a large but badly paid army whose upper ranks were monopolized by the royal family and aristocracy created the resentments that eventually led to the Communist coup.

Crews’s account explains why both last year and in 1989, when I visited Kabul and Herat on the government side, I found large numbers of educated people (who had not necessarily sympathized with either the Soviet or the US military presence) intent on supporting the Afghan state against the Mujahideen (then) and the Taliban (now), because—as many told me—they were determined to defend modern Afghan civilization against what they saw as rural conservative barbarism. But Crews cannot really explain the culture of the Mujahideen with whom I had previously traveled, or the Taliban today, or why so much of rural Afghanistan has supported these movements.

Along with the failure to modernize most of Afghanistan, there is also the failure to create a sufficiently strong sense of Afghan national identity in most of the population—a failure that itself reflects the inability to sponsor a really effective state education system. For while Crews casts doubt on the ancient, as opposed to constructed, nature of Afghan tribal identities (which have indeed changed greatly over the past century, and which have never been nearly as clear-cut or monolithic as naive Western stereotypes assume), the idea of the nation-state is obviously even more of a construct, and a much more recent one. For many Afghans, the idea of primary allegiance to the “Afghan nation” has had to compete with the rival and overlapping claims of loyalty to kin, to religion, to ethnicity, and to particular leaders.

The Taliban are in their own way strong Afghan nationalists, but for most of their leaders, the idea of Afghanistan is one based on the conservative religious culture of the rural Pashtuns of southern and eastern Afghanistan, somewhat modified by a puritanical Islamic reformism. So far, their ability to appeal to other Afghan ethnic groups like the Tajiks has been limited.

The most famous definition of a modern state is by Max Weber: “A human community that successfully claims a monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory.” By this standard, Afghanistan has had a modern state for barely thirty out of the past 135 years, and even for those thirty years only questionably. Throughout its history the Afghan monarchy faced tribal and religious revolts, one of which—in 1929—brought down the ruling dynasty.

Only at the end of the 1940s, with supplies of Soviet heavy weapons, did the Afghan army become strong enough to defeat a combined revolt of the main tribes (as opposed to allying with some against the others). In the thirty-seven years since the start of the revolt against the Communists in 1978, the Afghan state has never possessed a monopoly of armed force, not only because of large armed rebellions, but because it has itself repeatedly had to fall back on the help of autonomous warlords and their armed militias in order to survive. This was true of the Communist regime in its later years, when it formed an alliance with, among others, the Uzbek General Rashid Dostum; that he is now vice-president of the country is hardly reassuring. Nor is the fact that the group called the Afghan Local Police are often nothing more than local warlord militias.

Antonio Giustozzi charts this history in his latest book, The Army of Afghanistan: A Political History of a Fragile Institution—a work that will undoubtedly be the textbook on this subject. The importance of this book, however, goes far beyond its immediate subject. One of the reasons is that now, as in the past, the Afghan National Army is essential to the survival of the Afghan state. If the army collapses in the face of the Taliban, then, as in 1992 and 1929, not just the present Afghan regime but the state itself will fall and disintegrate—with no foreseeable prospect of it being put back together again.

The main problems of the Afghan army throughout its history have been those of the Afghan state more widely: lack of revenue, leading to inadequate equipment, poor and irregular pay, discontented and potentially rebellious officers, and demoralized soldiers who frequently desert; lack of even the basic necessary education among the soldiers, contributing to an inability to master modern equipment and conduct complex operations; lack of a strong sense of Afghan national identity and Afghan national loyalty among many of the troops; ethnic tensions, especially between the Pashtuns and the other nationalities; and factionalism, whereby sections of the army owe their chief allegiance to particular commanders and not to the state.

Two factors above all are likely to be crucial: the continuation of US funding and support, without which the army would collapse just as a previous Afghan state army collapsed when Soviet support ended at the end of 1991; and whether tensions between Pashtun and Tajik soldiers can be kept under control. For while, as recorded by Giustozzi, the US made great strides in turning the Tajik-dominated anti-Taliban forces of 2001 into an ethnically balanced force, many Pashtuns continue to allege Tajik domination, especially of elite units.

In Afghanistan, the old problem of units becoming in effect autonomous armed factions under their own chieftains also leads to local truces with the enemy. Giustozzi describes how both in the 1980s and today, local army commanders have reached such truces with the Mujahideen and the Taliban, to prevent local fighting and often to share the proceeds of the local heroin trade. I witnessed such local truces myself in the late 1980s.

As Giustozzi writes, of all the regimes that have ruled Afghanistan since the 1970s, the one that has been the most successful in creating armed forces that have both been matched to Afghanistan’s own resource base (as opposed to aid from a foreign backer) and willing to fight hard has been the Taliban. As a result of local taxation (especially of the heroin trade) and limited aid from Saudi Arabia and other sympathizers in the Gulf, the Taliban have been able to pay their fighters a reasonable wage. Unlike the National Army, they do not keep large numbers permanently in the field, they have not tried to acquire heavy weapons, and they do not possess elaborate and expensive command structures. The Taliban have also depended far less than other regimes (including the present government in Kabul) on the help of militias controlled by warlords.

Giustozzi ends his book with a strong call for a political settlement in Afghanistan. By this he means not only a peace settlement with the Taliban, but a stable consensus among the political elites in Kabul to allow the state and army to develop without constant factional battles. If such settlements can be achieved, then Afghanistan may be able to develop armed forces that can be supported from its own resources—not the present huge but US-funded force.

The call for serious moves toward a peace settlement is one that I strongly endorse. One should have no illusions that this can happen soon—but also not rule it out. The Afghan government has now committed itself to direct talks with the Taliban, talks backed by the Quadrilateral Coordination Group in which Afghanistan takes part with the US, China, and Pakistan. While the Taliban continue to make military progress on the ground, they have also suffered a serious internal split as a result of the death of their charismatic leader Mullah Omar. His official successor, Mullah Akhtar Mansour, has the support of most of the political leadership of the Taliban, but he is opposed by several top field commanders.

Even more importantly, the Taliban are under pressure from the Islamic State (ISIS), which has appeared in eastern Afghanistan and gained considerable support, including from Pakistani Taliban fighters driven out of their country by recent Pakistani military offensives. ISIS enjoys the position—unique as far as I know in regional history—of being feared and hated by almost every single state and movement in the area, including the mainstream Taliban, the Afghan state, Pakistan, Iran, Russia, the Central Asian states, and India. Just conceivably, therefore, hostility to ISIS might in future help to create the national and regional basis for a settlement.

Absent a settlement, the Taliban will continue to fight. Making a cease-fire a precondition for talks is senseless—what possible incentive do the Taliban have to agree to this? The real preconditions for a settlement are fourfold: first, that—as the Pentagon is arguing—the US make clear its determination to keep troops in Afghanistan in order to prevent the collapse of the Afghan state and an overall Taliban victory (though soldiers would be withdrawn as part of any settlement); second, that enough Taliban become convinced that a restoration of full Taliban control over Afghanistan is impossible (some at least already realize this, and know that even if the US withdraws completely, its place would be taken by India, Russia, and Iran); third, that Pakistan make good on its promise to bring real pressure to bear on the Taliban to agree to a reasonable settlement; and four, that the government in Kabul eventually come up with a peace offer that Mullah Mansour and his followers can accept. This offer would certainly have to involve a considerable share of power for the Taliban at the national level, and a dominant share in their core areas.

Any such offer would of course be bitterly unpopular with many people in both Afghanistan and the West. The alternative, however, appears to be unending war. However depressing it is to admit this, we need to acknowledge that while the Taliban do not represent anything like a majority of Afghans, they have demonstrated during their struggle of the past decade that they do have great and lasting support among rural Pashtuns, which shows no sign of going away. This sentiment and this force will have to be accommodated if Afghanistan is ever to know peace. If enough of the Taliban can be brought into Afghanistan’s political system, then there is reason to hope that with the unifying influence of the armed jihad much diminished, they will be more and more affected by the individual and tribal rivalries that have undermined all previous Afghan movements, and will eventually cease to exist as an armed and effective movement.