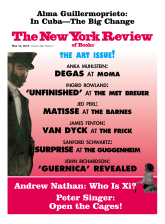

Peter Fischli and David Weiss/Jason Klimatsas/Fischli Weiss Archive, Zurich

Small clay sculptures from Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s series Suddenly This Overview (1981–present), which depict, according to Sanford Schwartz, ‘historical events, moments that might have been, and visualizations of age-old sayings and concepts we believe we ought to know,’ as well as ‘everyday scenes and objects.’ Clockwise from top left: Book and Reader, Galileo Galilei Shows Two Monks That the World Is Round, The Alchemist I, and The Dog of the Inventor of the Wheel Feels the Satisfaction of His Master.

Delightful and funny aren’t words one regularly associates with contemporary art, but they certainly fit aspects of the work of Peter Fischli and David Weiss. At least, I heard a fair amount of giggling at the Guggenheim Museum’s beautifully laid-out retrospective of the Swiss collaborative team. Not that they were exactly entertainers. (One speaks of their partnership in the past tense because, although Fischli is sixty-three, Weiss died in 2012, at sixty-five.) In work straddling photography, sculpture, films, installation art, and much else, they were more like wry magicians—and magicians with an underlying moral bent.

Their subject was the everyday, or real, world we all see and don’t pay much attention to and the random notions and musings that pass through our minds and that we tend to forget. Gentle, playful, and ironic, they sought to reshape ordinary and omnipresent objects and thoughts—without, in the process, losing sight of the ordinariness. Their ultimate point, one believes, was a kind of reclamation of the ignored.

The Guggenheim’s show provides the first comprehensive look New York has had of artists whose names have been familiar in the art world, and who have been seen in good-sized shows that traveled to American cities in previous years, but who remain, I think, barely known to the general museum-going public. The Zurich-based duo, who met in 1977—they connected through the new punk rock scene of that moment, which also influenced art and political activism—were in tune with each other from the first (and Fischli, since his partner’s death, has continued on projects left unfinished). Many of the hallmarks of the vast amount of work they created in the thirty-three years that they functioned together are present in their first venture. Called Sausage Series (and made before they thought of themselves as a team), it is comprised of a number of color photographs that they took of scenes of buildings, roads, events, excursions, and catastrophes—often with sausages as their main characters.

Seemingly anything the artists had lying around—cigarette butts, toilet paper, an egg carton—were props. In Fashion Show, sausages parade by, on a runway where the lights are sprigs of parsley, wearing different kinds of cold cuts, while a recreation of a scene in the James Bond movie Moonraker takes place in a refrigerator. In At the Carpet Shop, cornichons are contemplating various throw rugs (stacks of pimento loaf), though the star attraction is probably the big, round area rug (a slice of mortadella).

Fischli and Weiss’s transformations became far more challenging, but about their work one often finds the same combination of innocence and wit, impromptu manual dexterity and a desire to experiment with whatever is at hand. Their splashiest experiment with what was, roughly speaking, at hand is the thirty-minute movie The Way Things Go, a masterpiece of engineering, physics, chemistry, and hard, ingenious work that is guaranteed to hold the full attention of people seven or eight years old and up.

In this chain-reaction movie, which can be seen in a bay on the museum’s ramp, tea kettles, auto tires, slurpy liquids, explosions, springboards, fuses, fires, steam, mattresses, chairs, pails, and much else all take their part in nudging, flipping, and propelling one another along. The film, made in 1985 and 1986, is like a surreptitious look at the strenuously organized life objects make for themselves when people aren’t around. The Way Things Go is for many the first piece by Fischli and Weiss that they encounter, and it is surely their most widely known work.

But at the present show the movie takes its place as one of a number of novel and at first sight completely unconnected ways of reclaiming the ignorable. For viewers coming to the artists for the first time (and even for those who have seen a handful of their shows over the years), the Guggenheim exhibition might initially be mistaken for a group show, or a jigsaw puzzle waiting to be put together. In addition to their epic Way Things Go, Fischli and Weiss made other films and videos. As still photographers, they traveled everywhere, taking pictures of the world in what are essentially tourist shots (forming a compendium entitled Visible World and dated 1986–2012); and another collection of photos, Airports, is of jets idling on the ground or being serviced. The artists made figurative sculpture in clay and created installation art on the theme of construction sites. They found a way to make an artwork out of questions—often ephemeral, unanswerable ones.

Advertisement

There are also unclassifiable forays into the everyday. The 1990 Son et lumière—or Sound and Light, the title of nighttime shows outside historic buildings where a soundtrack and beams of light attempt to bring the place’s past alive—is one such foray and a takeoff of genius. In Fischli and Weiss’s version, a Swiss Army–issue flashlight has been trained on a little plugged-in turntable on which a plastic, faceted cup—held from falling off by a strip of masking tape—rolls back and forth. The light, refracted through the facets, sends ever-moving shards of lumière onto the wall, and the son comes as the cup goes here and there. This is the sweetest sound and light show you will ever see.

Yet at the Guggenheim we are given only the main aspects of Fischli and Weiss’s output. Many of their works were commissioned and, tied to particular sites, cannot be in the exhibition. (They are illustrated and discussed in its accompanying catalog, which, with its clear, perceptive descriptions and many quotes from the artists, forms an invaluable guide to their art.) For the new Swiss stock exchange building, for instance, in 1992, they placed museumlike vitrines everywhere, including the garage, and put in them store-bought objects of every description, from toys or knives to an accordion or a perfume bottle. A work realized for an art fair in Münster, Germany, in 1997, was a functioning flower and crop garden, and for a German power plant that commissioned a piece—to take one more example—there now exists a snowman, dating from 1987 to 1990, that is kept in existence year-round through a cooling system that the artists devised with the engineers.

Fischli and Weiss never spelled out the meaning of their art. It is clear, though, that they were opposed to the self-important and to hierarchies, whether in the art world or anywhere, and on the side of the reality we perhaps undervalue. Moralists though they were, they were always a step or two ahead of their audience in finding ways to fashion the uncenteredness they believed in. Question Projections is a memorable and novel way of presenting it. The work is set in a darkened room at the top of the Guggenheim ramp where a viewer finds, projected onto the wall from a battery of slide projectors, question after question (written out, in flowing, curvy lines, in German, Italian, Japanese, and English).

David Heald/Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Painted polyurethane foam sculptures of buckets, cleansers, paint rollers, and other items in Fischli and Weiss’s series of work sites (1991–present), installed at the Guggenheim. ‘Once you understand that each (perfectly realized) item you see is phony—and, as carved foam, is light as a feather and easily smashed,’ Sanford Schwartz writes, ‘you may find it hard to tear yourself away from looking.’

The questions are those that occurred to the artists over many years. Although the question “Can I re-establish my innocence?” seems personal to them—surely their Sausage Series and Visible World, their tour of the planet’s beauty spots, owe a great deal to a desire for innocent looking—the questions in general don’t get us closer to the persons Peter Fischli and David Weiss. Perhaps due to their quietly militant belief that we can all do with fewer hot-air personalities, one learns strikingly little about the artists’ personal lives in the Guggenheim’s hefty catalog.

In Question Projections we are given instead a peek into the minds of most people, where serious, absurd, spur-of-the-moment, and fantastical thoughts are forever flowing in and out of each other. The point would seem to be the connectedness of these thoughts. It is underscored by the clip at which the questions come and go, and by the fact that most viewers probably look for the questions in only one of the languages but can’t help paying a little attention to those they don’t understand. Yet I, for one, found hierarchies asserting themselves.

Questions on the order of “Should I eat chalk?” or “Does a ghost drive my car at night?” seem merely fey and like filler. But “Can one do everything wrong?” or “Why is it called daybreak?” have a poetic substance, and the question “Is a mistake around today that’s as big as the idea of the earth being flat?” is an oddity from left field that puts one on pause. Thomas Aquinas and Woody Allen might both be absorbed by “Is my indecisiveness proof of my free will?”

Advertisement

Suddenly This Overview, which the artists began working on in 1981 and kept returning to, tackles in an entirely different way what passes through the minds of most of us. The many small clay sculptures that make up the opus present historical events, moments that might have been, and visualizations of age-old sayings and concepts we believe we ought to know. But the sculptures, most of which can be held in two hands, are also of everyday scenes and objects—a woman at a supermarket, a housing development—and these pieces fit right into the flow. We feel, with the endless variety, that we are seeing every person’s inner and outer lives.

Fischli and Weiss liked to do some of their works in great number. Visible World and Airports are each made up of many hundreds of examples, the point presumably being the erasure of distinctions between important and unimportant. But the experience of these photo collections is such that after seeing a few (this is particularly the case with Airports) our minds wander and we move on. With Suddenly This Overview the sense of abundance is vividly experienced. At a certain point on the Guggenheim’s ramp we become surrounded on every side for some distance by 168 diminutive gray (or unfired) clay sculptures, most on separate white pedestals and some on the wall. Seeing this vast assembly of small works from far away (a possibility few museums can offer as well as the Guggenheim) is like viewing a major fleet at sea.

Each of the little gray sculptures seems to present a different miniaturized experience from the one next to it, and once you start looking you don’t want to miss any. It is a joy to go from a presentation of a slice of real life (a car on a mountain road; a boot; a plate of olives) to the deadpan absurdity of The Invention of the Miniskirt (she stands in her skirt as a tailor cuts part of it off), or to jump from the remarkably uneventful subject of waiting for an elevator (a person stands before two closed doors) to The Landing of the Allies in Normandy (the concise version). There are folk-art-like illustrations of sayings or situations—in Artist and Audience a singing bird is appreciatively looked at by another bird—and moments of inspired slapstick, such as Free Market Economy, imagined as an intertwined pile-up of thrusting, grasping buffoons.

In some of their best pieces, Fischli and Weiss work as dramatists, inventing new ways to see the quotidian spirit they celebrate. In Mr. and Mrs. Einstein Shortly After the Conception of Their Son, the Genius Albert, we look down into an ultra-plain little room with a person sleeping in each of the two single beds, blankets neatly drawn up. The only problem with such a conception of the ordinariness that underlies the momentous is that it takes the bloom off such related pieces as Anna O. Dreaming the First Dream Interpreted by Freud (set in a mousy, underwhelming bedroom), or The Dog of the Inventor of the Wheel Feels the Satisfaction of His Master. That Einstein’s parents might be the most memorable characters in Fischli and Weiss’s mammoth run-through of life is fitting since their art is about relativity, if not exactly Einstein’s version of it.

Many if not most of the clay sculptures take on their full meaning because of their titles, and the titles make us wonder how different these works are from New Yorker cartoons. The First Fish Decides to Go Ashore, for instance (you can imagine what it looks like), is a subject that we half-believe we have seen in the magazine. The difference is the clay, which often has its own life. Although Fischli and Weiss each made his own sculptures, we seem to look at a single house style. It is one where the tension derives from seeing in what detail the artists have built up, or carved out, forms from such a slablike, obdurate-looking, and unpromising material.

Carving is an ingredient in what for me is Fischli and Weiss’s richest series: their creations of work sites. At the top ramp of the Guggenheim you come across bays that look like they are being made ready to present art (or are being fixed up after some displays have come down). Why, we wonder, has the museum forgotten about this? Left in stacks on the floor or propped against a wall, or seen in the form of pedestals or boxes of all sizes, are wood boards, many with white primer slapped on and many bruised through handling. On a large work table there are cleansers and containers of glue, power tools and paint rollers in their pans, and markers, pliers, and plastic utensils. A club chair touched with plaster dust is in a corner, and paint-bespattered work shoes are set to the side. I could add juice cartons, pallets, rolls of tape, a level, soda cans, rubber work gloves—and more.

For viewers coming to the Swiss artists for the first time, the experience of these work sites will be, I believe, one of perplexity followed by dawning incredulity and then smiles, because everything we see has been carved out of polyurethane foam, which has then been painted. Once you understand that each (perfectly realized) item you see is phony—and, as carved foam, is light as a feather and easily smashed—you may find it hard to tear yourself away from looking. Even in photographs in the catalog, these and other polyurethane carvings—sometimes seen in warehouselike settings where they have been placed among standard-issue, mass-produced chairs, desks, tools, and appliances—cast a spell. Knowing that some pieces are painted foam but not knowing which makes everything seem animate.

The work sites, which Fischli and Weiss began fashioning in the early 1990s, are very much outgrowths of their concerns. The tableaux certainly make us rethink (or at least look twice at) objects we take for granted; and making work environments into art is ingeniously in accord with the moral underpinnings of the artists’ endeavor, their sense that art is, firstly, work and not the expression of individual genius. One of their videos, Untitled (Venice Work), is a ninety-six-hour-long accumulation of scenes of people going about their various jobs; and an aspect of The Way Things Go that struck Fischli was how much the making of that movie was a group, or leaderless, act. “Who is the artist?” he asks about it in an interview in the catalog.

The polyurethane installations, moreover, are about the labor that goes into art. They give us the backstage life of nearly every gallery and museum presentation. Whether or not the artists intended it, the spirit of these installations is not only irony, or a transformation that makes one question what is real, but realism itself. The spaces that these polyurethane buckets and boards are set in, we come to feel, are not empty backgrounds. As we get our bearings on these works, we can see that each bay at the museum has a subtly different installation (or two), and the spaces become imaginable as actual rooms. We look at the carpentry and cleaning materials—and at the cigarettes stubbed out in ashtrays, the ripped-open bag of candy, and the bottle of Tylenol left in a corner—and think of the workers who might have been here. The scenes before us seem as much portraits of activity as of being finished for the day.

In some sense, Fischli and Weiss’s work sites show them to be realists in traditional ways. Presenting spray cans, pizza boxes, and broken-in work shoes, the artists made me think of the Chardin who took scullery maids and governesses for his central characters and of the Degas who for a period painted laundresses and milliners. Fischli and Weiss’s trompe-l’oeil realism actually quite closely recalls the paintings of bins of old books and other leftovers by the late-nineteenth-century American painter John F. Peto.

But the Swiss artists’ tools and bottles aren’t stand-ins for emotional purity, which Chardin conveys, and they don’t suggest the tedium of labor, which Degas can convey. Peto’s affinity for, it seems, the pathos of objects is absent. In all their work Fischli and Weiss give us, rather, a comic, unexpected, rejuvenated realism—or, really, awareness of the mundane, their muse. They clear a space where we can take a breather from heroes and villains and stark, inflammatory contrasts. What one comes away from the show with, however, isn’t a sermon on parameters, modesty, and the equality of everything. It is the opposite: a sense of amazement in the face of the artists’ ability to find so many ways to reimagine sanity.