A startling shift in perspective occurs as we read—and remains with us after we have read—the title poem in Robin Coste Lewis’s first collection, Voyage of the Sable Venus and Other Poems, which received the 2015 National Book Award in Poetry. The poem is an incantatory compilation of the names of art works, catalog entries, and scholarly texts describing “Western art objects in which a black female figure is present, dating from 38,000 BCE to the present.” Lewis’s ambitious narrative poem is itself a kind of catalog that alters the way we see and think about a wide range of visual art. It affects our view of the historical, political, and cultural climate in which that art was created, collected, exhibited, and preserved.

In a prologue, Lewis explains the guidelines that determined her principles of selection of art objects portraying black women and the process of composition. The titles of the works were to remain intact and unaltered, though the grammar and punctuation of the names and the texts were modified: “I erased all periods, commas, semicolons.” The following passage illustrates how the poem’s idiosyncratic orthography increases its music, wit, and mystery, even as the reader may succumb to the temptation to reassemble, for greater clarity, the fragments of language:

Anyonymous speaking at memorial for Four Negro Girls

killed in church bombing in Birming. Ham.President Kennedy addressing the crowd: A Red Boo!

A Negro Boo! Young Girls being heldin a prison cell at the Leesburg

Stockade. Wounded, civil.Rights demonstrators in the hospital

and on the street-burned-out-bus:Bronzeville Inn Cabins for Coloreds. Here lies

Jim Crow drink Coca-Cola white.Customers

Only!

In compiling her list, Lewis tells us, she broadened the definition of art beyond the categories of painting, sculpture, and photography that are customarily employed by art historians. That definition is expanded here to include objects—“combs, spoons, buckles, pans, knives, table legs”—that incorporate the figures of black females as design elements. She has included black women who passed for white, and, in some cases, has chosen to use a museum’s description of a work rather than its title.

Lewis makes a cogent case for her use of black rather than African-American:

At some point, I realized that museums and libraries (in what I imagine must have been either a hard-won gesture of goodwill, or in order not to appear irrelevant) had removed many nineteenth-century historically specific markers—such as slave, colored, and Negro—from their titles or archives, and replaced these words instead with the sanitized, but perhaps equally vapid, African-American. In order to replace this historical erasure of slavery (however well intended), I re-erased the postmodern African-American, then changed those titles back. That is, I re-corrected the corrected horror in order to allow that original horror to stand. My intent was to explore and record not only the history of human thought, but also how normative and complicit artists, curators, and art institutions have been in participating in—if not creating—this history.

In addition, Lewis “decided to include titles of art by black women curators and artists, whether the art included a black female figure or not” and “work by black queer artists, regardless of gender, because this body of work has made consistently some of the richest, most elegant, least pretentious contributions to Western art interrogations of gender and race.”

“Finally,” she writes, “with one exception, no title was repeated,” an explanation that clarifies passages such as the one below. It is helpful (and dismaying) to learn that an object is not unique but belongs to a larger group of works employing similar imagery:

Heraldic Lion Holding

Between His Paws the Headof a Kneeling Black Captive

Statuette of a Negro Captive KneelingHands Bound Behind Back

Negro Youth Strugglingwith a Crocodile Negro

Youth Struggling with a CrocodileNegro Youth Struggling

with a Crocodile PygmyArmed with a Stick Statuette

of a Black Girl with Her HeadInclined Toward the Left

Shoulder Dagger with DecorationIn Relief Lion Devouring a Black Head

of a Black Nude Black Serving Girl

Just under eighty pages long, “Voyage of the Sable Venus” begins with two epigraphs that together exemplify—and provide a preview of—Lewis’s insistence on letting historical documents speak for themselves and her fondness for juxtaposing passages of profound horror with examples of institutional racism so benighted that they might almost seem comical, were they not so distasteful. The second of these epigraphs is a request from a Mrs. B.L. Blankenship, an antebellum Virginian: “I am anxious to buy a small healthy negro girl—ten or twelve years old, and would like to know if you can let me have one…” The first, particularly apt for a work that addresses the subjects of curatorial practice, art history, and museum display, is a party announcement:

Advertisement

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Employee’s Association Minstrel Show and Dance

will be held at the American Woman’s Association

361 West 57th Street, Saturday evening,

October 17, 1936

The poem is divided into sections arranged in roughly chronological order, beginning with Ancient Greece, Rome, and Egypt, and ending in the modern era. A list of damaged objects from classical antiquity comes to seem like a roster of injuries sustained by human victims:

Statuette of a Women Reduced

to the Shape of a Flat PaddleStatuette of a Black Slave Girl

Right Half of Body and Head Missing…Figure’s Left Arm Missing Head

of a Female-Full-length Figureof a Nubian Woman

the Arms Missing…Partially Broken Young Black Girl

Presenting a Stemmed BowlSupported

by a Monkey

Unsurprisingly, the most distressing verses are lists of works made during (or portraying) the period of the Middle Passage. Powerfully evocative, easy to picture despite the brevity with which they are described, the images flip past us: slavers throwing the dead and dying off a slave ship; an auction at which a “Negro Man in Loincloth/serves liquor to Men Bidding/on The Slaves while A Slave Woman/attends Two Women Observing The Sale”; “Two Black Overseers/Flogging Two Negro Slaves/One a Nude Man Suspended from a Tree/The Other a Woman.”

The most chilling sections read like logs of evidence with line breaks; they are incontrovertible proof of the violence that occurred during a shameful era in our history:

In a Grove of Trees Slave Woman wearing a Runaway.

Collar with Two Children, emaciated.

Negro Man eating Dead.Horseflesh in the background.

Negro Man strapped to a ladder, Being.

Lashed Slave Woman seenfrom the back, her head in left

profile, kneading bread and smoking

a Pipe Parrot Vendor Negress.Carrying Her Young Slave Woman

carrying Baby and Negro Boy, running.

At Left Negro Man at right, Being.Held by the collar, two dogs wear

collars, one labeled “Cass,”

the other: “Expounder.”

Amid these litanies of misery and pain is a description of an image that readers might register as a temporary lightening of the mood, an example of racist kitsch that stands, in contrast to the floggings and murders, much as the announcement of the Metropolitan Museum’s blackface ball follows the politesse and brutality of Mrs. Blankenship’s inquiry regarding the purchase of a child:

Nude Black Woman

in an Oyster ShellDrawn by Dolphins

through the Waterand accompanied by Cupids,

Neptune, and Others.

These lines describe Thomas Stothard’s etching The Voyage of the Sable Venus from Angola to the West Indies, an odious representation of a near-naked black woman awkwardly posed on a shell balanced on the backs of two ill-tempered dolphins and surrounded by acrobatic, plumed white cupids and a buff, sinewy Neptune. This image accompanied the third edition of Bryan Edwards’s The History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies in the West Indies (1801), a volume that contained Isaac Teale’s long poem “The Sable Venus: An Ode.”

The most-often-quoted verse of Teale’s rambling, wretched work reassures the erotic adventurer seeking “fond pleasure…ready joys…and all true raptures” that, in the dark, a black female body is no different from the pale goddess at the center of Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus. What makes the picture and the poem repellent is not merely the crudeness of sentiment and expression, but the fact that they were composed when black women, far from being ferried by dolphins and venerated as deities, were regularly chained and transported in the holds of cargo ships.

However familiar we may be with the history of slavery, we’re freshly astonished and appalled by the realities to which these disturbing images testify: by and large (with the obvious exception of the black Venus), they were not works of the imagination; an artist might have witnessed such scenes or heard about them from an eyewitness; and such pictures could have been considered suitable for the decoration of homes.

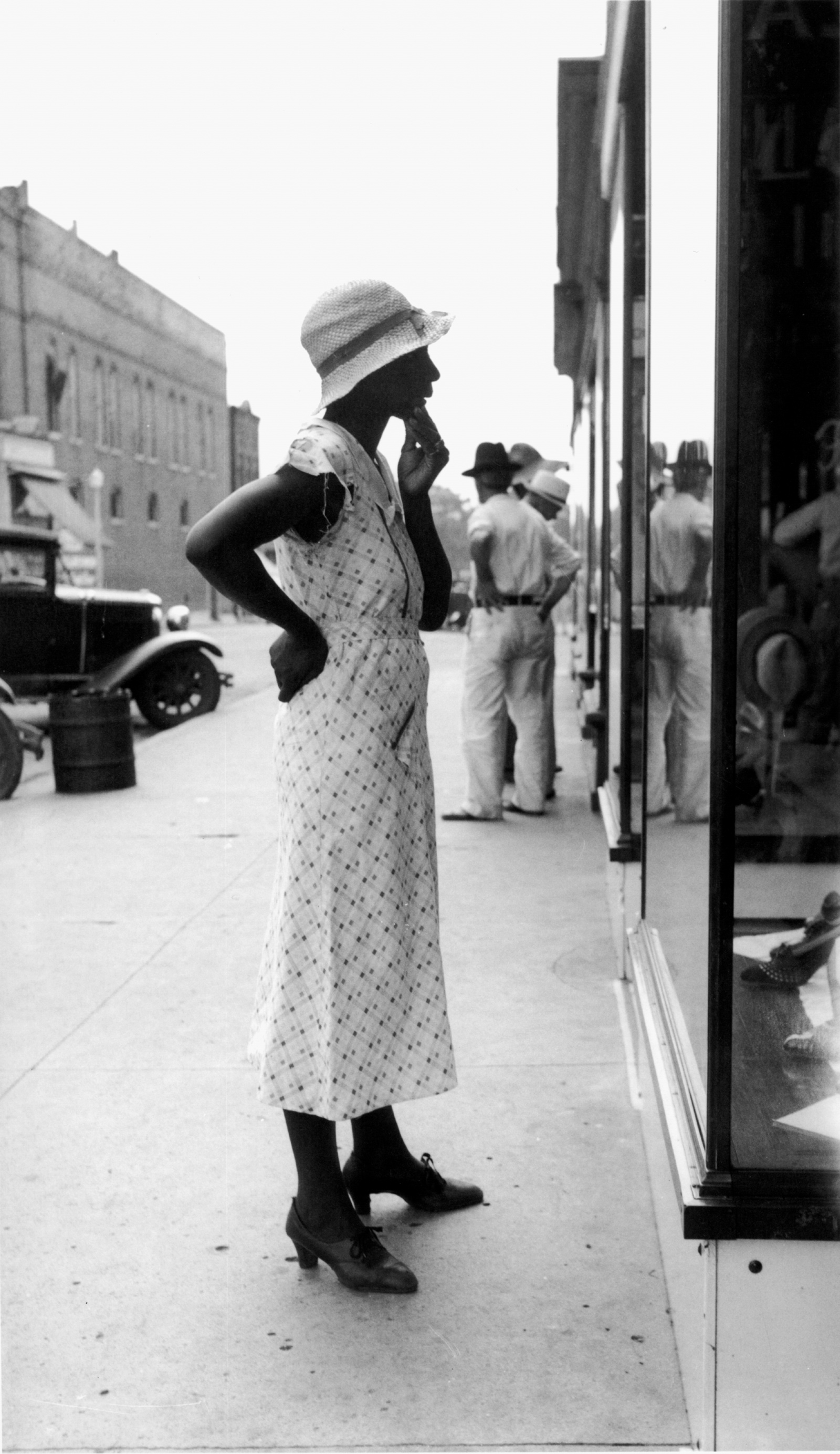

It is to Lewis’s credit that she never denies, ignores, or underestimates the complexities and contradictions of her subject matter. One such contradiction confronts us even before we open the first page of her attractive, elegantly designed volume. Taken from one of history’s most degrading visions of a black female, the collection’s title shares the book’s cover with Window Shopping, Eudora Welty’s lovely photograph, printed here in sepia tones: a remarkably different depiction by a white artist of a black woman looking into a store window. Though the photo was taken in the 1930s, in Jim Crow Mississippi, it transcends the preconceptions and prejudices of that time and place. It’s hard not to see it as a loving homage to its subject’s beauty, grace, dignity, self-possession, and sense of style; and, in addition, as a study of the contemplative reverie into which any of us, of any color, can slip as we stand in front of a store window.

Advertisement

The latter sections of the poem move briskly through more recent centuries and into the present. Abraham Lincoln makes an appearance, “holding/a Kneeling Black Woman/by the wrist/and lifting Her/to Her Feet.” The ceremonial solemnity of this vision and its implicit promise of a more egalitarian future is instantly undercut by the images that follow: three children, one white, one red, one black, are being held in the arms of Charity, while a Chinese person holds Charity’s drapery. A black man and a white man, “His Arm/Around a Small Negro Girl,” shake hands inside a wreath of sugar cane stems.

As we move into the modern era, the tone of the poem becomes less harrowing and turns lively, even joyous. Presumably, this is because many of the images in Lewis’s poem have been created by black artists whose works express a more informed, thoughtful, sympathetic, and celebratory view of black women, as well as an understandably different and frequently angry or wry perspective on race relations.

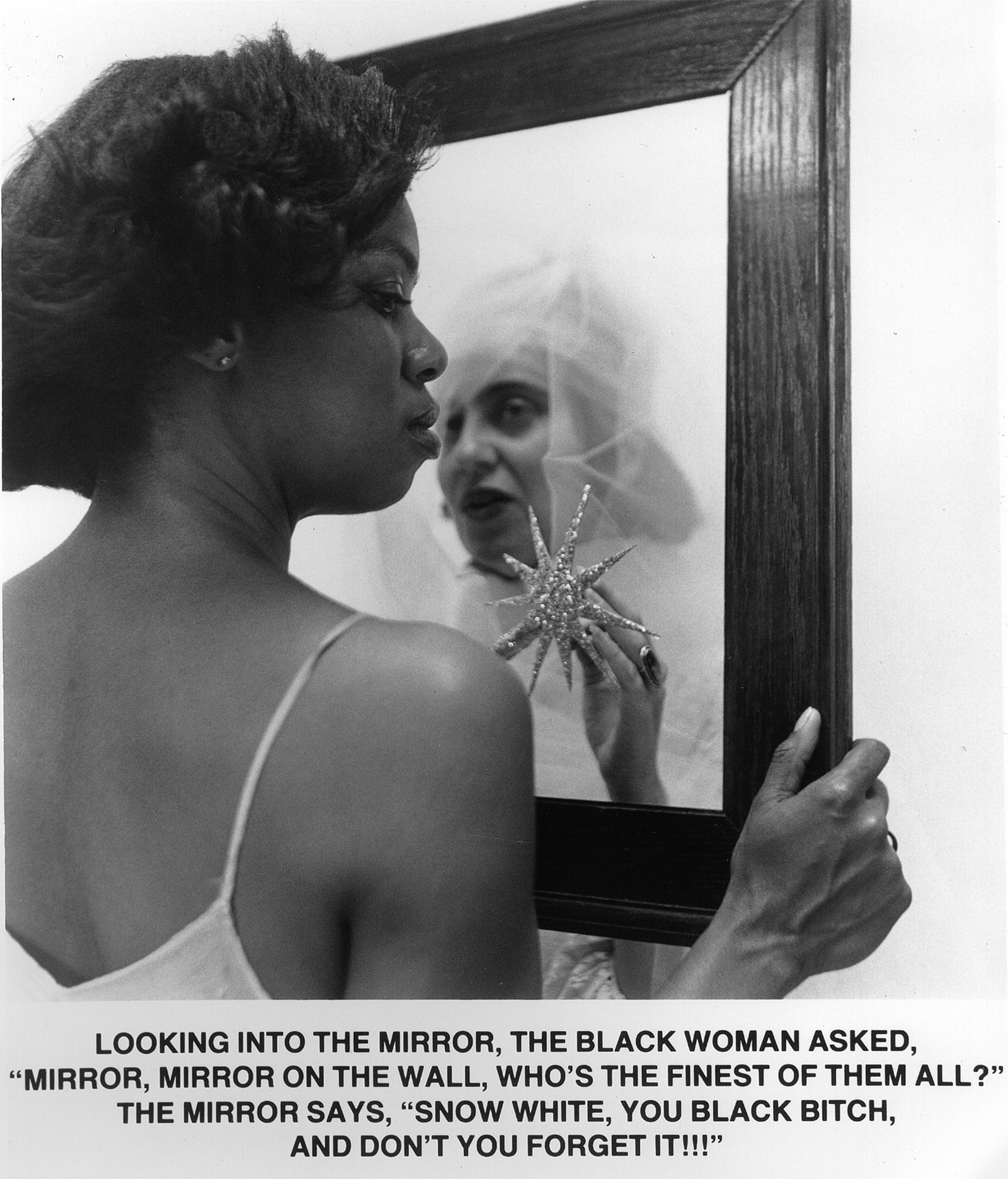

Lewis is generous and respectful in her appreciation of the scores of writers and visual artists responsible for dispelling the stereotypes and misconceptions so prevalent in the past. Among the works she mentions are The Sweet Flypaper of Life, a collaboration between Langston Hughes and the photographer Roy DeCarava; Lynn Marshall-Linnemaeir’s “Annotated Topsy series”; a painting by the vernacular artist Nellie Mae Rowe; a photograph by Carrie Mae Weems with a caption that reads, “looking into the mirror/the Black Woman asked/‘Mirror, Mirror on the wall,/who’s the finest of them all?’/The Mirror says,/‘Snow White/ you Black Bitch,/and don’t you forget it’”; and a Kara Walker installation entitled “‘They waz Nice/White Folks//While They/Lasted’//(Says One Gal/to Another.)”

What has mattered since the Dadaists first experimented with found poetry—verse pieced together from scraps of spoken and written language, from texts not originally intended to be literary or poetic—is what matters still: the artfulness with which the poet fashions this sort of collage. At moments Voyage of the Sable Venus may remind one of how, in Testimony: The United States (1885–1915): Recitative, Charles Reznikoff demonstrated (as Charles Simic noted in the NYR Daily*) that a rich vein of poetry can be mined from documents as ordinary and unpolished as court trial transcripts; a section of Reznikoff’s poem entitled “Whites and Blacks” portrays race relations fully as fractious and oppressive as the inequities and injustices that fuel the anger underlying much of Lewis’s work.

The success of the effects that the poet achieves with the raw material on hand is what distinguishes work like Reznikoff’s and Lewis’s from so-called conceptual poetry, whose practitioners (among them Kenneth Goldsmith) argue, less convincingly, that a poem can be made by arranging nonsense syllables, or by obsessively recording every tiny gesture made during a day of the poet’s life, or by simply retyping a page from a newspaper.

Lewis’s focus on the language in which the images are described rather than on the images themselves concentrates our attention and makes it easier to grasp the themes and patterns that emerge. As we read this unillustrated catalog, information reaches us in short, telegraphic bursts, without the distractions of detail, or color, or composition, without inciting or satisfying the desire to walk around a sculpture or to spend the length of time required to fully experience a painting. But many readers will want to see the works to which Lewis refers—beginning with the image from which the collection takes its title. They may find themselves finishing the poem and heading for a museum or an art library or, more likely, consulting the Internet.

Lewis’s engagement with complication and contradiction is equally evident in the two groups of autobiographical poems that surround “Voyage of the Sable Venus.” The first and last poems in the collection touch on the ramifications of knowing that one’s ancestors were slave-owning blacks, a population that Edward P. Jones wrote about beautifully and perceptively in his novel The Known World (2003). Both the opening and the final poems include the words “the black side of my family owned slaves,” and both explore the grief and shame of having made this discovery:

Tonight, after twenty-five years,

I realized I’ve spent my entire lifeavoiding any situation

that might require me

to say these words aloud.

Some of the most memorable passages in these shorter lyrics make reference to visual art, as if Lewis’s fascination with the implications of a graphic image had been allowed to spill beyond the strict parameters that govern the composition of “Voyage of the Sable Venus.” The poem “From: To:” considers the new and heady experience of freedom enjoyed by black infantry soldiers serving in World War II, men who, in a photograph, have gathered around a bomb on whose casing they have scrawled a personal message:

At last, a dark murderous lunatic

to whom they are allowed to respond.

Here, no one expects them to be strung

up by their necks—dangled—and then leftto be cut down from a tall tree—and not cry…

…They find some

chalk to celebrate. While one loads, one lifts,

then checks. Just before they ignite the bomb,they write on its shell—FROM HARLEM, TO HITLER—

then stand back for the camera, smiling.

The poem “Frame” begins with memories of childhood (Lewis was born in Compton, California, and her family is from New Orleans) and includes, near its end, an image that, as Lewis describes it, floats into our minds like a photograph coming up in a tray of developing fluid. It’s Joseph Louw’s well-known photograph of a small group of people on the balcony on which the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. has just been murdered and is lying at their feet. Several of them are pointing up, apparently in the direction from which they believe the assassin has fired his gun.

Our textbooks stuttered over the same four pictures every year: that girl

in the foreground, on the balcony; black loafers, white bobby socks, black skirt, black

cardigan, white collar. Her hand pointing. The others—all men—looking

so smart, shirt-and-tied, like the gentle men on my street, pointingas well, toward the air—

the blank page, the well-worn hollow space—

from which the answer was always

the same hoary thud.Every year these four photographs

taught us how English was really a type of trick math:

like the naked Emperor, you could be a King

capable of imagining just one single dream;or there could be a body, bloody

at your feet—then you could point at the sky;

or you could be a hunched-over cotton-picking shame;

or you could swing from a tree by your neck into the frame.

Voyage of the Sable Venus and Other Poems changes the manner in which we read the texts on museum walls, in galleries, and in art books—with sharpened attention but happily (thanks to Lewis’s wit, the ingeniousness of her method, and the complexity of her perspective) without the sense of grievance or the harsh, censorious judgment that might spoil our appreciation of the works on display. Underlying Lewis’s critique, one intuits, is a frank acknowledgment of the seductiveness of aesthetic pleasure, of the power of beauty, in almost every case, to trump our moral reservations about the settings in which the beautiful objects were created. In an interview, Lewis has said of the image of The Voyage of the Sable Venus from Angola to the West Indies, “It’s really horrible. It’s beautiful and horrible simultaneously.”

When we are in their presence, the gorgeous, fragmented statues from Egypt and classical antiquity don’t in fact remind us of the physical damage suffered by the black women they represent. Lewis’s book doesn’t diminish our enjoyment of art but rather enhances it by encouraging us to formulate a more conscious way of thinking about what we are seeing.

Among the virtues of the collection is the intensity of Lewis’s faith in the power of language and image to tell us things that are true, but that are rarely said, about history, race, gender, power, the body, scholarship, and visual representation. In providing us with a revelatory gloss on centuries of art, Robin Coste Lewis has made us aware of the enormity of the change reflected and perhaps partly brought about by contemporary black women artists whose vision, originality, and humor offer a heartening corrective to the ghastly insult of the Sable Venus.

-

*

Charles Reznikoff, Testimony: The United States (1885–1915): Recitative, with an introduction by Eliot Weinberger (Godine, 2015), reviewed by Charles Simic in “A Brutal American Epic,” NYR Daily, August 25, 2015. ↩