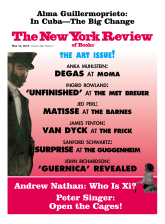

Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Ivan Maisky (second from left), the Soviet ambassador to London between 1932 and 1943, with Winston Churchill at the Allied ambassadors’ lunch at the Soviet embassy, September 1941. General Władysław Sikorski, prime minister of the Polish government in exile, is second from right.

Could World War II have been avoided? Or if not avoided, since Hitler was Hitler, could it have been postponed until the Western democracies were better prepared to defeat him? A credible threat in 1938 from the Soviets, backed by the British and French, to come to the aid of the Czechs might have stopped Hitler in his tracks. The Soviets had issued such a guarantee to the Czechs in 1932, but it was contingent on the French keeping their part of the bargain. In 1938, Hitler gambled that the Soviets and the West would never stand against him together. At Munich in 1938 British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier sold out the Czechs and proved him right.

This question—of whether the war could have been avoided or at least delayed—dominates the diaries of Ivan Maisky, Soviet ambassador to Britain throughout the grim decade of appeasement. Maisky enjoyed extraordinary access to the entire British elite, because he had been a Menshevik exile in London between 1912 and 1917 and had established friendships with Sydney and Beatrice Webb, G.D.H. Cole, and George Bernard Shaw. Upon becoming ambassador in 1932, Maisky consolidated these friendships on the Labour left, while assiduously cultivating figures on the Conservative right, notably Winston Churchill.

In these diaries, Churchill, then in the political wilderness, emerges as the figure who most clearly understood that the Western democracies’ only chance of deterring Hitler lay in an alliance with the Soviet Union. In 1936, Churchill told Maisky: “We would be complete idiots were we to deny help to the Soviet Union at present out of a hypothetical danger of socialism which might threaten our children and grandchildren.”

In 1937 at a state banquet Churchill broke off a conversation with King George VI in order to engage Maisky in a probing discussion of whether Stalin’s purges of the Party and the army, then reaching their paroxysm, would leave Russia too weak to face Germany. While Churchill’s attentions to the Russian ambassador were being carefully noticed in the room, Maisky blandly assured him that the purges would strengthen, not weaken the country. Churchill shook his head distrustfully and remarked, “A weak Russia presents the greatest danger for the cause of peace and for the inviolability of our Empire. We need a strong, very strong Russia.”

The purges did the cause of a Soviet-Western alliance against fascism no good at all. Maisky himself barely survived these purges—the diary breaks off for long periods when he returned to Moscow for chastisement and reeducation—but his usefulness to Stalin as a conduit and source of information seems to have saved him. The pressure on Maisky can only be imagined: members of his London staff were called home and executed; his wife’s relatives were sent to the gulag and she suffered a nervous breakdown. Sixty-two percent of the top-level Soviet diplomats were wiped out. Not even in his diary, which he wrote secretly, did Maisky confess his own terror and anxiety.

Stalin’s purges led many, including the American ambassador, Joseph Kennedy, to doubt that the Soviets were capable of standing up to Hitler. Kennedy (“tall, strong, with red hair, energetic gestures, a loud voice, and booming, infectious laughter—a real embodiment of the type of healthy and vigorous business man that is so abundant in the USA”) told Maisky that “the Brits claim…you would not be able to help Czechoslovakia if it were attacked by Germany, even if you wished to.” Maisky insisted this was not so, but the impression Kennedy retained of this exchange gave him another reason to advise Roosevelt to stay out of a European war that Kennedy believed Britain and France were bound to lose.

As Chamberlain prepared to go to Berchtesgaden to discuss Czechoslovakia with Hitler in mid-September 1938, Maisky journeyed down to Churchill’s estate at Chartwell. Churchill showed him a brick cottage he was building with his own hands, “slapped the damp and unfinished brickwork with affection and pleasure,” and assured the Soviet ambassador that Chartwell was “not a product of man’s exploitation by man,” but entirely paid for by Churchill’s royalties. The purpose of Maisky’s visit was to get Churchill to tell Chamberlain’s foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, that the Soviets had promised they would protect Czechoslovakia, provided the French did so too. This, Maisky hoped, would stiffen the British position in their negotiations with Hitler in Munich later in September 1938. It was too late. Chamberlain and Daladier gave Hitler a free hand to absorb the Sudetenland and extinguish Czech freedom. After the capitulation, Maisky went to commiserate with Jan Masaryk, the Czech ambassador in London. The young Masaryk sobbed on Maisky’s shoulder and whispered: “They’ve sold me into slavery to the Germans.”

Advertisement

By the time of Munich, the anti-appeasement alliance between Conservative grandees like Churchill and Labour politicians like Clement Attlee and Arthur Greenwood had taken shape. Greenwood is a forgotten figure now, but it was he, Maisky tells us, who really ripped into Chamberlain in a private meeting after Munich. When Chamberlain tried to persuade Greenwood that Hitler was “an honest man” and could be trusted, Greenwood cut him off: “Have you read…Mein Kampf?”

Maisky’s failure to warn his masters in Moscow of the outcome in Munich put him in mortal danger back home. For a time he feared recall to the USSR and disappearance into the gulag. To reassure his masters, he placed a menacing full-length portrait of Stalin in military uniform in the reception room of the embassy, “so displayed as to dominate the room.” In March 1939, when Hitler was about to absorb the rest of Czechoslovakia, Chamberlain began to edge closer to the Soviets, visiting the Soviet embassy, but with Hitler’s invasion of Poland now barely six months away, it was too late. Even at this penultimate hour, Chamberlain assured Maisky, with glassy-eyed self-delusion, that neither the German nor Italian people wanted war.

Recalled to Moscow in April 1939 for a terrifying tête-à-tête with the boss, or vozhd, as Stalin was known, Maisky was instructed to return and gain, even at this late hour, a commitment from Britain that it would not seek a separate peace with Germany. In May, however, Stalin changed course. He suddenly dismissed Maisky’s oldest friend and protector, Maxim Litvinov, from his post as foreign minister, leaving Maisky, in the words of the diary editor, Gabriel Gorodetsky, “the sole genuine exponent of a pact with the West.” Once again, what saved Maisky was his irreplaceable access to the British elite. Stalin feared the British and French would make a “second Munich,” this time at the Soviet Union’s expense, and so he kept Maisky on to give him advance warning of such a possibility.

Maisky continued to try to negotiate an Anglo-Soviet agreement against Germany throughout the summer of 1939, all the while confessing to his diary: “What, in fact, can England (or even England and France together) really do for Poland…if Germany attacks…?” The vozhd evidently concluded the same and the Anglo-French-Soviet negotiations broke down in August 1939.

What replaced them—the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact between Germany and the Soviet Union in August 1939—appears to have come as a thunderbolt to Maisky, at least if the diary is to be believed. A nonplussed Maisky could only write, with feeble understatement, “Our policy is obviously undergoing a sharp change of direction….”

With the Soviets neutralized, Hitler struck at Poland on September 1, 1939. Ever the agile apparatchik, Maisky was soon parroting the new line. As German troops advanced on Warsaw from the west, Soviet troops invaded from the east, seizing eastern Poland and Belorussia, as Maisky piously put it, “in order to protect the population’s lives and property.”

Surprisingly, even after the Hitler-Stalin pact, senior British leaders continued to receive Maisky. In a meeting in October 1939 at the Admiralty with Churchill, Maisky sought to persuade the new Sea Lord that Stalin would never go to war against Britain and France. Churchill appears to have believed him, but few others did. Maisky was ostracized by polite British society, as Britain faced Hitler alone. By May 1940, as Germany swept through Belgium, France, and Holland and drove the British army back to Dunkirk, Maisky wrote in his diary that “the Anglo-French bourgeois elite is getting what it deserves” for its “mortal hatred of ‘communism’” and its failure to make common cause with the Soviet regime.

In June 1940, Ambassador Kennedy came to see Maisky and they agreed, at least if Maisky is to be believed, that the upper classes of British society were “completely rotten.” So worried did Maisky become about a British collapse in 1940 that he asked for instructions from Moscow about how to “conduct myself if the Germans were to occupy the district in London in which our embassy is located.” Being Jewish, Maisky would not have been surprised to have found himself on a list, apparently circulated in Berlin at that time, of the people Hitler had ordered to be shot once Britain was occupied.

Even when the Hitler-Stalin pact left Britain to face the German onslaught alone, after the Russians invaded Poland, working people in Britain continued to harbor affection for the Russian people. In the autumn of 1940, during the German bombardment of London, Maisky visited bomb shelters in East London and was astonished to be greeted with cheers from the crowd, some singing the “Internationale” and one old lady, her “face webbed with wrinkles,” crying out, “Our Russia is still alive!”

Advertisement

In mid-June 1941, Churchill authorized disclosure to Maisky of evidence, collected from code-breaking of German signals, that Hitler was about to attack the Soviet Union. So suspicious was Stalin that Britain and Germany would strike a deal against Russia that he refused to believe the British warnings. When Hitler attacked across the Russian border on June 22, 1941, the Soviet command was caught by surprise and Soviet forces fell back pell-mell.

Once the Soviet Union was finally on Britain’s side, Maisky became the courier between Stalin and Churchill, relaying personal messages to Chequers, then sitting and taking tea with Clementine Churchill, watching while Churchill absorbed them. As early as the summer of 1941, Stalin demanded a second front in Europe, and from the beginning Churchill refused. Achieving the second front became Maisky’s dominant objective in London for the remainder of his ambassadorship. He stirred up the British Communists, the trade unionists, and everyone in a broad left front to demand an Allied landing in Europe to ease the pressure on the heroic Soviet ally. Sovietophilia reached its zenith in 1942 and 1943 and this common front atmosphere created a London social scene—never seen before and never to be seen again—in which Lord Beaverbrook thought there was nothing odd about keeping three portraits on his mantelpiece (Stalin, Roosevelt, and George VI) and Maisky supped at Beaverbrook’s table with Averell Harriman, Roosevelt’s envoy; Churchill’s daughter-in-law (with whom Harriman was having an affair); and the left-wing journalist Michael Foot.

Already in 1943, the diaries lay bare the grim outlines of the postwar order that Stalin would impose once his armies rolled into Eastern Europe. Maisky, dealing with the Polish government in exile in London, parroted the vohzd’s brutality toward the Poles. Maisky writes: “It is difficult to escape the conclusion that Poland is generally incapable of prolonged and sustained existence as a fully independent and sovereign national organism.” Years before it happens, in other words, the extinction of Polish freedom is already prefigured in these diaries.

As the Soviet armies began to sweep everything before them in late 1943, Maisky and Anthony Eden, his closest confidant in the British government, began to dream of what the postwar world would look like. Maisky told Britain’s foreign secretary, “What will the world look like, say, in the twenty-first century? It will, of course, be a socialist world.” Of course, and for good measure, he added, the twentieth century will not be the American century, but the Russian. By then, Maisky was so close to Eden that Churchill had to order his foreign secretary not to share Churchill’s correspondence with Stalin with the Soviet ambassador.

In the spring of 1943, Churchill and Roosevelt decided in Washington not to launch a second front in Europe that year, choosing instead the assault on Italy. Stalin was furious: his ambassador had not delivered the second front, and he was now expendable. Maisky suddenly found himself yanked home and dismissed by the vozhd. Terrified of what would happen on his return, Maisky instructed his wife, “whatever happens,” to send copies of his diary—which he called “My Old Lady”—to Stalin himself, in what appears to have been a desperate attempt to prove that even in the private recesses of his mind, he had remained loyal.

Back home, he tried to live down his fame in London and work his way back into favor. He translated for Stalin briefly at Yalta and at Potsdam, but the old dictator dressed him down brutally and Maisky understood that his life hung by a thread. At the end of the war he sought survival by becoming an academic at the Russian Academy of Sciences. His colleagues—Maxim Litvinov and Alexandra Kollontai—died, and he hung on in the increasingly paranoid last years of Stalin’s life, only to be arrested for spying for the British and interrogated in the basement of the Lubyanka prison in the final months before Stalin’s death in the spring of 1953. In a poem written from prison to his wife on his seventieth birthday, Maisky lamented:

I lived life in a major key…

And now my star has flickered out

in a dark sky,

And the way forward is hidden in a

dark shroud,

And I meet this day behind a stone

wall….

He was eventually released by Khrushchev in 1955 and allowed to write his memoirs. He died in 1975. He was the canniest of survivors, but his survival was not pretty: he lied, confessed to crimes he’d never committed, allied himself with the notorious butcher Lavrenti Beria in the tumultuous battle for succession after Stalin died in order to exonerate himself, but somehow managed to come out in one piece, preserving his diaries and his version of events.

His diaries, recovered from Russian archives and superbly edited by Gabriel Gorodetsky, are exceptionally vivid. Whether they are trustworthy is another matter. He was an exceedingly intelligent, agile, but always vulnerable servant of a tyrant, and as such, he censored even his private thoughts, but this lends his diaries a special fascination, as you watch a vain and clever man maneuvering to survive in the middle of a Europe heading toward the abyss.