The last words of the dying painter Thomas Gainsborough in 1788—“We are all going to Heaven, and Vandyke is of the party”—serve as a reminder of the enduring presence of Anthony Van Dyck in the world of English portraiture during the centuries after his death. A Flemish protégé of Rubens, born in 1599, he had precocious success in Antwerp before making the great and necessary trip to Italy, where he paid particular attention to Venetian art, especially that of Titian. He made his base in Genoa, where, over a century later, in 1780, a guidebook estimated that there were still visible, in the palaces and churches of the city, no fewer than ninety-nine paintings by Van Dyck, of which seventy-two were portraits.

Antwerp bore him, Genoa raised him to his preeminence as a portraitist of the nobility, but it was in England, at the court of Charles I, that he achieved the most extraordinary monopoly on the imagination of posterity. For it is impossible to think of Charles and his wife Henrietta Maria, and the great figures of his court, without seeing them as Van Dyck portrayed them. And this portrayal has an unmistakable tinge of advocacy. It was hard for those born after to look on Charles’s noble features without thinking of his beheading as a form of martyrdom:

As I was going past Charing Cross

I saw a black man upon a black horse.

They told me it was Charles the First.

My God, I thought my heart would burst.

The anonymous nursery rhyme’s response to Hubert le Sueur’s bronze equestrian statue of 1633 (still on the south side of Trafalgar Square, where the king looks down Whitehall toward the place of his execution) has sometimes been taken to be a satire. But it is entirely plausible as a record of genuine, abiding shock at the killing of the king. In the same spirit, Van Dyck’s images of Charles were copied endlessly. They turn up in cottages and in stately homes. The huge equestrian portrait depicting the king with his riding master, M. de St. Antoine, which is in the Royal Collection, became familiar recently to millions of television watchers: a copy hangs above the breakfast table in Downton Abbey (Highclere Castle in real life). But they hang in numerous other great houses as well.

This success in promulgating his own image (like a Roman emperor, or like the French Sun King) belonged not only to Charles but also to his right-hand man, whom Charles was forced to betray: Thomas Wentworth, First Earl of Strafford. Beheaded in 1641, the year of Van Dyck’s own premature death, Wentworth seems to turn a particularly piercing gaze at us, a look of anger and alarm. Here’s another figure from our imagined history. I grew up in the village of Wentworth, where the half-ruined old church contained a monument to Thomas Wentworth, and on that monument, as I recall, was Wentworth’s own helmet—though it seemed far too small for a man. But as I looked up at the helmet I was reminded of what I had been told could be seen at night in Wentworth Woodhouse nearby: the figure of Thomas Wentworth, First Earl of Strafford, walking down the staircase, with his head tucked under his arm.

The king and his court, the doomed Cavaliers of the future civil war, men and women of great power and wealth and almost above all, in the eyes of posterity, incomparable style—the broad flat collars, the lustrous silks or satins, the magnificent soft leather boots of the men—a style that lived on through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It lived on through the work of artists like Gainsborough, whose painting of the Blue Boy is an exercise in the Van Dyck style. And the Blue Boy lived on in our era: it became a jigsaw puzzle, a biscuit tin, a do-it-yourself tapestry kit, a song. Meanwhile Van Dyck himself became both a noun and a verb—a kind of beard, a brown pigment, a flat collar with deep-cut points…

That a foreign artist could come to London and monopolize an era may sound surprising. But it is not surprising. It had happened before. Hans Holbein the Younger, born in Augsburg in Germany a century before Van Dyck, trained in Basel in Switzerland, came to London, and stayed to paint Henry VIII and various of his wives and other family members, and to draw a large number of the members of the court. Once again, one cannot think of the era without in some sense seeing it through Holbein’s eyes. The difference is that Holbein’s style did not remain as an inspiration to later generations of painters. It was eclipsed by that of Van Dyck.

Advertisement

Jonathan Richardson the Elder, portrait painter and art theorist, wrote in 1715:

When Van-Dyck came Hither, he brought Face-Painting to Us; ever since which time (that is, for above fourscore Years) England has excell’d all the World in that great Branch of Art, And being well stor’d with the Works of the greatest Masters, whether Paintings, or Drawings, Here being moreover the finest Living Models, as well as the greatest Encouragement, This may justly be esteem’d as a Complete, and the Best School for Face-Painting Now in the World.

By implication, this excludes from consideration not only Holbein, but also the whole native tradition of portraiture (including beloved miniaturists such as Nicholas Hilliard and Isaac Oliver). Richardson admired Holbein and owned work by him, but he probably thought of his portraiture as coming into a different category. The art Van Dyck introduced to England was portraiture in the tradition of Titian and Raphael. This remained the living idiom, well into the nineteenth century.

We can tell very clearly what it was that the English painters saw in Van Dyck (and what sometimes disappointed them), because they have told us. Here is Jonathan Richardson the Younger, in Florence, making his discovery of the portrait of Cardinal Bentivoglio, the star exhibit at the Frick’s terrific new show:

I never saw anything like it. I look’d upon it two Hours, and came back twenty times to look upon it again. He sits in an Elbow Chair with one of his Elbows upon the Arm of the Chair and his Hand (the most Beautiful and Graceful in the World) falls carelessly in his Lap by the other, which most unaffectedly gathers up his Rochet [linen vestment], which is painted beautifully, but keeps down so as not to break the Harmony. His Face has a Force beyond anything I ever saw, and a Wisdom and Solidity as great as Raffaele’s but vastly more Gentile.

Indeed it must be confess’d the Difference of the Subjects contributes something to this Advantage on the side of Van Dyck. The Colouring is true Flesh and Blood, Bright, and Transparent; Raffaele’s is of a Brown Tinct and something Thick, at least compared with this. His Scarlet is very Rich and Clear, but serves nevertheless to set off the Face, ’tis so well manag’d. The Picture is enrich’d with things lying upon the Table, which unite with the Cardinal’s Robes, and Flesh, and make together the most pleasing Harmony imagineable.

This is impressively remembered. A century later, after the fall of Napoleon, the portraitist James Northcote discussed with fellow painter James Ward the following ticklish question:

If Titian, Vandyke, and Sir Joshua [Reynolds] had all been alive at the same time, I wonder which of them would have painted the best portrait of Bonaparte! It is dreadfully difficult to decide. Now Titian would have given him a grandeur bordering on the terrible; Vandyke, an elegance bordering on dandyism; Sir Joshua would have lost none of the sweetness of his character. Upon the whole, Titian, I think, would be my choice.

Upon the whole, it seems, Titian is going to win in these games of comparison, although Van Dyck is always of the company, always in the top echelon. And the quality being valued most by Northcote is a kind of realistic impact bordering on the uncanny:

When any stupendous work of antiquity remains with us—say a building or a bridge—the common people cannot account for it, and they say it was erected by the devil. Now I feel this same thing in regard to the works of Titian;—they seem to me as if painted by a devil, or at any rate from inspiration; I cannot account for them; Vandyke’s things don’t produce that effect upon me at all, for his portraits are like beautifully-executed models standing up in glass cases, such as are to be see in Westminster Abbey [he is referring to the wax funeral effigies]. But Titian’s have a frightful look of life about them, and it is this which astonishes me.

Northcote, too, had been to the Pitti Palace and stood before the portrait of Cardinal Bentivoglio, which was hung beside Titian’s portrait of Cardinal Ippolito dei Medici in Hungarian dress,

and you have no idea how like a mere drawing Vandyke’s looked to me when I cast my eyes from one to the other; and yet it is one of Vandyke’s most powerful works! It suffered sadly from its powerful neighbour, and Vandyke would have felt this keenly if he had seen it in the Palace Pitti under the circumstances that I did. But, then, nothing will stand against Titian!

Northcote, whose conversation was so valued by his contemporaries that two writers—Ward and William Hazlitt—took care to record it at length, is not always consistent in these comparisons, but he reveals some underlying criteria. He says at one point that Van Dyck’s portraits “look too much like the members of one family”; elsewhere he finds this fault in Titian:

I am afraid to think it, yet I cannot help thinking sometimes, that Titian was a mannerist, for his portraits, though identity itself in many respects, yet have all the same solemn air—they partake of his own sternness of character. Now to get rid of self is the great thing to be aimed at, and this, in my opinion, Titian did not quite manage to accomplish. Raphael managed it better, but no man did it as well as Shakespeare, which makes the miraculous part of his character.

So the first quality Northcote was looking for in a painter was a capacity for self-effacement in the manner of Shakespeare—the Romantic, inscrutable Shakespeare evoked in Matthew Arnold’s later sonnet (“Others abide our question. Thou art free”). In some respects, he thought that Van Dyck’s paintings were the finest in the world—“they are exquisite in execution, and cleanness of color, and are perhaps the best models to learn how to work from”—but there is too much of the artist himself in them: “The airs and attitudes of Vandyke’s sitters are not theirs, but his own.”

In execution, the thing to be avoided, Northcote thought, was excessive linearity or what he called “lininess”:

Men may go to the same place by different roads. Nothing can surely be more unlike than the manner of Titian and that of Vandyke, and yet the end they both had in view was the same. Now, if I were to proceed on Vandyke’s method of making outlines, I should produce nothing but dry lininess, I should never obtain a rich effect in my pictures; but, still, the method may suit another painter very well, as it did Vandyke, for instance, whose great power of execution enabled him to avoid lininess….

Lininess (though not, I think, dry lininess) might be used to describe the technique of Holbein, where the precision and elegance of the line account for a great deal of the effect of the painting, and where the preparatory drawings for the portraits bear a close relationship to the paintings. What counts with Van Dyck is not so much the line as the brushstroke—it is a different kind of precision, a precision of effect. Van Dyck possessed this from an early age—it is no doubt what Northcote refers to as his “great power of execution.”

As for the preparatory drawings, it seems often to have been the case that they concerned themselves with the sitter’s pose, rather than with the likeness of the face. As a mature artist, Van Dyck preferred to paint the features directly onto the canvas, working first in monochrome to create a sketch that would, in due course, disappear under paint. If a large-scale composition made this approach inconvenient, he might first paint oil sketches of individual heads. Two such sketches are on display at the Frick. They are lively and delightful and very much to the modern taste. But their quality has only recently been recognized. They had usually been overpainted in order to make them appear like finished portraits.

According to his early biographer, G.P. Bellori, it was Rubens who, having first trained and employed Van Dyck as his assistant and copyist, pointed the young man in the direction of portraiture:

It occurred to Rubens that his disciple was well on the way to usurping his fame as an artist, and that in a brief space of time his reputation would be placed in doubt. And so, being very astute, he took his opportunity from the fact that Anthony had painted several portraits, and, praising them enthusiastically, proposed him in his place to anyone who came to ask for such pictures, in order to take him away from history painting. For the very same reason Titian—even more harshly—dismissed Tintoretto from his house; and many other artists who have followed a similar course have in the end been unable to repress brilliant and highly motivated students.

The allusion to Titian’s alleged treatment of Tintoretto is perhaps enough to make us suspect that the story of Rubens’s jealousy of Van Dyck is a topos, a traditional tale redeployed to suit the circumstances. It did not convince Horace Walpole for one minute. “If Rubens had been jealous of Vandyck,” he asked, “would he, as all their biographers agree he did, persuade him to visit Italy, whence himself had drawn his greatest lights?” And Walpole continues with a marvelously tart observation: “Addison did not advise Pope to translate Homer, but assisted Tickell in a rival translation.” Jealousy, in other words, is not generous.

One can imagine, though, that Van Dyck’s was a personality that was at its happiest when it had achieved the status it craved—that of being the leading figure of his circle, the primus inter pares. Bellori gives us a sense of this when describing Van Dyck’s ill reception among the Flemish painters in Rome. Van Dyck’s manners, he tells us,

were more those of an aristocrat than a common man, and he was conspicuous for the richness of his dress and the distinction of his appearance, having been accustomed to consort with noblemen while a pupil of Rubens; and being naturally elegant and eager to make a name for himself, he would wear fine fabrics, hats with feathers and bands, and chains of gold across his chest, and he maintained a retinue of servants. Thus, imitating the splendor of Zeuxis, he attracted the attention of all who saw him. This conduct, which should have recommended him to the Flemish painters who lived in Rome, in fact stirred up against him the greatest resentment and hatred. For they were accustomed at that time to live cheerfully together, and it was their practice, when one of them was newly arrived in Rome, to take him to supper at an inn and give him a nickname by which he was afterwards known.

Van Dyck refused to go along with this, and was criticized for his pride and contempt for his fellows. Hence the decision, according to Bellori, to base himself in Genoa rather than Rome.

One can see that there might be something in Northcote’s observation, cited above, that the airs and attitudes of Van Dyck’s sitters are not theirs, but his own. He aimed for magnificence, like Rubens. He dressed magnificently and, as Bellori describes his house in London, he lived like a prince, “keeping servants, carriages, horses, musicians, singers, and clowns, who entertained all the dignitaries, knights, and ladies who visited his house every day.” He employed models to pose in the borrowed costumes of his sitters, and he had assistants to work up those parts of the portraits to which, in due course, he would put the finishing touches. It must have been an efficient system. During the London years, from 1632 until Van Dyck’s death in 1641, he painted more than 260 portraits that have survived, and, as Stijn Alsteens reminds us in the Frick catalog, many more that are now lost.

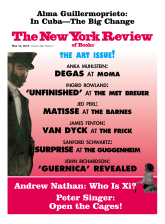

In 1999, Antwerp and London combined to mount an exhibition of Van Dyck’s paintings, both portraits and religious works. In London, it effortlessly filled the grand suite of the Royal Academy, and I remember vividly, on completing the circuit, looking back at the great tall rooms and thinking how well the generous architecture showed off the grandeur of the canvases. To an extent, the scale of the portraits reflects the elevated ranks of the sitters. The Frick’s beautiful early portraits of Frans Snyders and his wife are suitable both in scale and in idiom for an Antwerp painter of the time, and for his domestic space: they do not offend against the sumptuary conventions of the day. The Genoese full-length portraits, destined for palaces, develop their own sense of a palatial architecture. The largest of the English portrait groups, at Wilton House, could never have traveled. But the Frick, whose exhibition space is well known to be limited, was working against the odds in choosing to mount a Van Dyck show. It was pushing the envelope.

And the envelope consented to be pushed. Unlike in the 1999 exhibiton, the choice of work is confined to portraiture—the religious paintings (Van Dyck was a devout Catholic) are simply not addressed. But this concentration opens up a whole field of interest not investigated in 1999: the drawings and other works on paper. For although, as already said, Van Dyck seems to have avoided the need for preparatory portrait drawings of faces, when he could do so, his was the kind of talent, the kind of genius, that could turn its hand to whatever seemed necessary: there are (though obviously not in this show) beautiful landscape and plant studies, and even a few watercolors, among his oeuvre.

At the Frick, two rooms on the main floor are devoted to the full-sized portraits. In the basement are smaller paintings, including three precocious self-portraits, and drawings, grisailles, and etchings from a project that is really Van Dyck’s memorial to the Antwerp of his day, known as the Iconographie. This was a loose collection of portraits of painters, collectors, intellectuals, princes, and generals that were made to be engraved. There is something of a prejudice today against engraving as an art. It is at one remove from the work of the artist’s own hand, whether that work was an etching or a drawing or one of these fascinating paintings en grisaille, which come from the collection of Peter Lely, Van Dyck’s successor artist in Restoration London.

Van Dyck made very few etchings, but they are of extraordinary quality, especially when seen in their earlier states. The self-portrait, the head of Snyders, the drawing and the etching of Pieter Breughel the Younger—you realize what Van Dyck would have done had he chosen to pursue this kind of work. There is much that he didn’t do—he didn’t have a late style, for instance; he didn’t live long enough, dying at forty-two. One feels though that there was nothing he could not have done, had the occasion arisen.

Stijn Alsteens and Adam Eaker, both from the Metropolitan Museum, put together the exhibition and its substantial catalog, to which they both contribute excellent essays. One learns a lot. One has a good time.