The search for patterns, root causes, and overarching forces is universal, shaping thought about the visual arts as it does every other field of inquiry. But there are times when this search, admirable and essential as it is, can blind us to the powerful part that less predictable forces play in artistic creation: vagrant thoughts, backward or sideways glances, accidents, coincidences, escapades, obsessions, misreadings, even outright mistakes. Of all the modern masters, Matisse was the one whose art and life were most complexly shaped by the dynamic interaction between large patterns and unpredictable particulars. The arguments about what made Matisse the artist he was—what made Matisse Matisse—began more than a century ago with his emergence as the king of the Fauves, by some measure the most adventurous colorist in the history of art, and have never really been resolved. Sometimes he himself seemed unsure of who or what he was.

The publication of Matisse in the Barnes Foundation—a three-volume catalog of one of the greatest collections of his work, produced under the supervision of Yve-Alain Bois, a prominent figure among art historians—provides a fine occasion to return to these questions. This considerable achievement ought not be viewed in isolation, for Matisse is almost always in the public eye. Less than a year after the immense exhibition of his cutouts closed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in February 2015, the Morgan Library and Museum mounted an important show, “Graphic Passion: Matisse and the Book Arts,” focusing on an essential and too often overlooked aspect of his achievement.

Every decade brings fresh approaches to Matisse, a notable book of recent years being Henri Matisse: Modernist Against the Grain, by Catherine Bock-Weiss.1 And if we are to take the measure of Yve-Alain Bois’s views of modern art, it helps to look not only at his earlier work on Matisse, particularly the essay “Matisse and ‘Arche-drawing’” in his 1990 book Painting as Model, but also at the first volume of the catalogue raisonné of Ellsworth Kelly’s paintings, reliefs, and sculptures, which appeared last fall. Kelly, who died in December at the age of ninety-two, is often viewed as the inheritor of Matisse’s coloristic gifts, and for the catalogue raisonné Bois has written an extensive series of commentaries on the work Kelly did in France, where he lived between 1948 and 1954.

Among the works in the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia are more than fifty paintings by Matisse, including major achievements from nearly every period of his career. Albert Barnes, a chemist who made a fortune in the pharmaceutical industry, did not begin collecting Matisse as early as the Russian Sergei Shchukin or Gertrude and Leo Stein and their brother Michael and his wife Sarah. But once he did so in 1912 Barnes was unstoppable, acquiring from the Steins important works, including the boisterous pastoral Le Bonheur de vivre, and commissioning from Matisse in 1930 his first major mural, The Dance. The Barnes collection ranges from daringly distilled works of the pre–World War I period, including Red Madras Headdress and Seated Riffian, through some of the richly articulated nudes of the 1920s, down to a couple of the rapidly painted interiors of 1947, which are among Matisse’s last and in many respects still least studied and admired paintings. Barnes, who saw the function of his foundation as largely educational, published in 1933 one of the first major books on Matisse, written with Violette de Mazia, his close collaborator at the foundation.

Yve-Alain Bois has shaped and directed the Barnes’s multivolume Matisse catalog, while limiting his own writing in it to a long essay, “Matisse’s Awakening,” and leaving the extensive entries on the paintings to Karen K. Butler and Claudine Grammont. In “Matisse’s Awakening” Bois focuses on The Dance, the mural that fills the arched spaces above the three windows in the foundation’s main gallery. This is by any measure a major achievement. There are two versions, the first of which is now in Paris, because a serious miscalculation of the size of the space forced Matisse to begin anew after more than a year’s labor. In working out the enormous composition, Matisse resorted to cutting and manipulating sheets of painted paper, so that the mural became a prelude to the cut-paper compositions of his last years, which many regard as his definitive rejection of the constraints of old-fashioned easel painting.

The Barnes Foundation

Matisse’s first major mural, The Dance (1932–1933), commissioned by Albert Barnes in 1930 and installed at the new Barnes Foundation museum building in Philadelphia in 2012. Below are works by William James Glackens, Matisse, Picasso, and Maurice Brazil Prendergast.

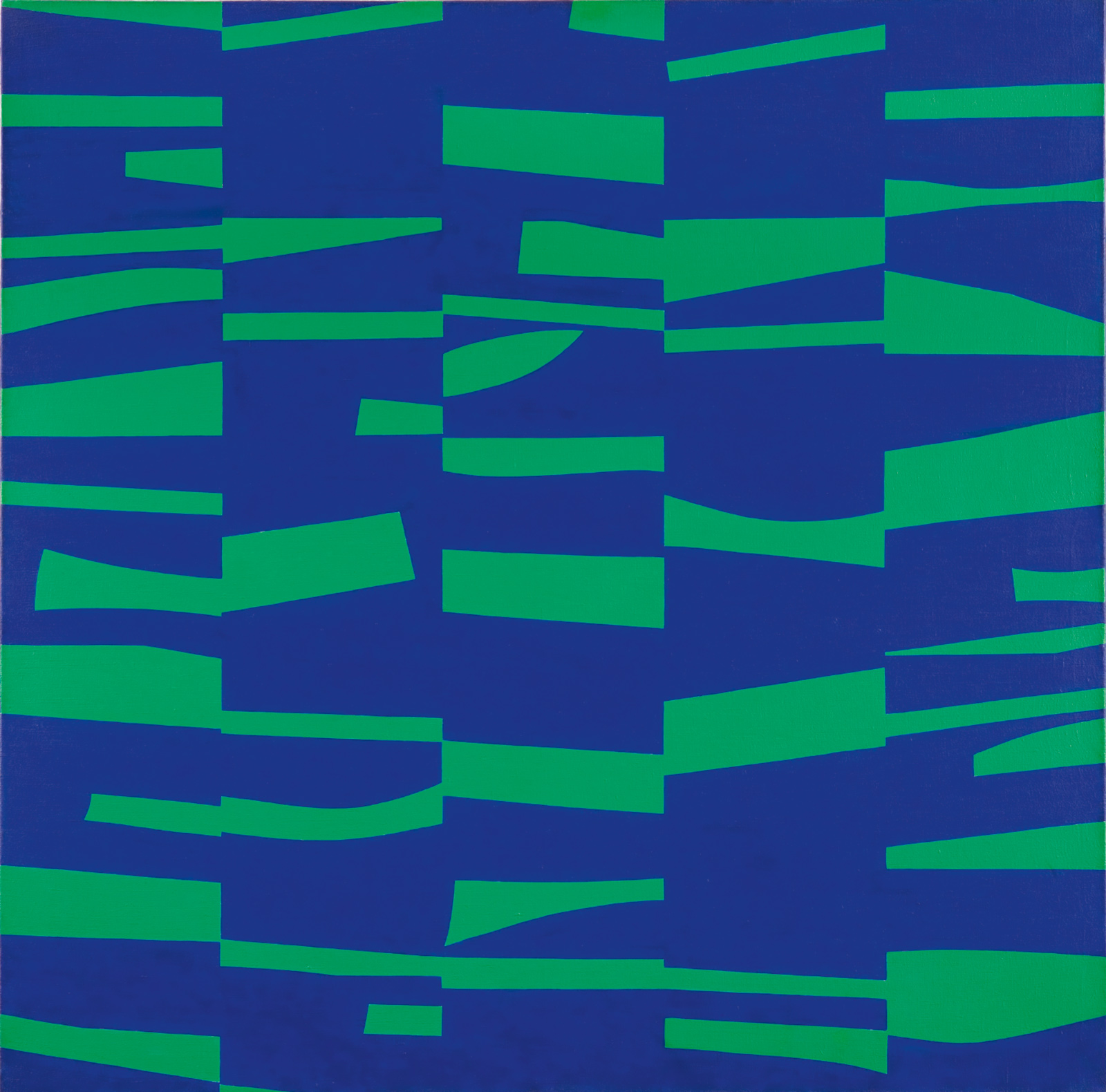

Advertisement

In the Barnes Dance, with its eight female figures, the Dionysiac heat of the circles of dancers Matisse had created more than twenty years earlier (in Le Bonheur de vivre and what is known as Dance II (1909–1910), commissioned by Shchukin for his Moscow mansion) are recapitulated and transformed, imbued with a dramatically different accent and timbre. The vehement red, green, and blue of Shchukin’s Dance II give way at the Barnes to a cooler, almost chilly orchestration of black, gray, gray-blue, and dusky pink. The linear arabesques now have a less tightly wound, less spring-like power. The figures are heavier, slowed down. The Barnes Dance is a recollection or memorialization of a dance.

Longtime admirers of Yve-Alain Bois will not be surprised that he has focused on The Dance, with little or nothing to say about the many paintings in the Barnes collection that date from the end of World War I to the early 1930s. They include studies in subtle visual complication and idiosyncratic naturalism such as The Venetian Blinds (1919), Young Woman Before an Aquarium (1921–1922), and Moorish Woman (1922–1923). Bois is quite frank about there being a Matisse who engages him very deeply and a Matisse who engages him far less. He favors the Matisse who simplifies and reduces, who aims for broad, succinct effects. What interests him is the Matisse he refers to as “the great innovator of the prewar years.”

As for the “other” Matisse—the Matisse who cultivates labyrinthine spatial ambiguities and intricate layerings of patterns and colors—Bois sympathizes with those critics who long ago “cast doubt” on his “inventiveness.” While careful to not exactly dismiss any phase of Matisse’s achievement, Bois makes it clear that he prefers Matisse when he is operating with what he says “could be called a ‘system,’ a coherent set of principles that were codependent and that governed his entire production.” Bois sees the more naturalistic Matisse of the post–World War I decade as unsystematic. And he applauds what he describes as a return in the Barnes mural to a system with color “at its core,” although of course naturalism has its own forms of systemization, which apparently interest Bois less.

While there is nothing exactly crude or peremptory in Bois’s division of Matisse’s work, I think he is much too willing to impose his own system of values on the artist. His preferences put him in good company, for there is a long history of critics attempting to shoehorn the infinitely variable Matisse into some particular set of values. Bois makes much of a 1930 essay, “Henri Matisse at Sixty,” by the Russian-born critic André Levinson, a figure still revered in the dance world for his appreciations of early modern ballet. In “Henri Matisse at Sixty,” Levinson was already arguing that there were two Matisses. He believed there was “a discontinuity between the two,” and that “the second had neglected, evaded, and tacitly disavowed the first, whose discoveries were epoch-making.”

In the capacious pages of the three-volume catalog of the Barnes Matisses there are certainly many sympathetic observations on his work of the late 1910s and 1920s, even efforts to bring together the two Matisses. In a penetrating essay on The Venetian Blinds Claudine Grammont argues, for example, that through the plangent naturalism of this radiant interior Matisse “expanded his field of visual possibilities” in ways that “prefigure the search for immateriality” in his work on the stained glass windows for the Vence Chapel at the end of the 1940s. Of course for Grammont, Matisse’s idiosyncratic realism is mostly significant as a prelude to what many regard as the more radical or experimental works he did later on.

However one judges Matisse’s achievement, nobody can gainsay its multitudinous nature. In Henri Matisse: Modernist Against the Grain, Catherine Bock-Weiss characterizes his output as “varied, uneven, and to a large extent incoherent in style and media,” and speaks of the “brilliant and fractured patterns” in his life and work. My sense is that Bock-Weiss is excited by these complications, which seem to her to underscore the inadequacy “of our received notion of modernism, our overdetermined and prescriptive notion of which art merits the title ‘modernist.’” She devotes an entire chapter to André Levinson’s essay on the two Matisses.

Even Clement Greenberg, a critic always eager to engage the central issue and clarify a situation, was impressed by Matisse’s magisterial ambiguities. In a little book about Matisse published in 1953, Greenberg comments that the artist “has never been able to come to rest in any one solution.” He argues that the fact “that Matisse strove for serenity and at times condescended to elegance and erotic charm ought not to deceive us as to the doubts underneath.” These observations are hardly disinterested. For Greenberg, Matisse’s “doubts” and “questioning” are somehow to be celebrated, whereas “serenity,” “elegance,” and “erotic charm” are more of a problem. Greenberg aims to resolve this dilemma, observing that “in this constant questioning of his own work…we recognize the type of the great modern artist.” But the exploration that leads to “elegance” and “erotic charm” is not the sort of search that generally holds Greenberg’s attention.

Advertisement

Behind all the talk about Matisse’s divided self—whether from Levinson, Greenberg, or Bois—looms a larger question, about the nature of artistic evolution. When Greenberg, in 1957, wrote that “like any other real style, Cubism had its own inherent laws of development,” or Bois, in his essay “Painting: The Task of Mourning,” included in Painting as Model, speaks of “the task that historically belonged to modern painting (that, precisely, of working through the end of painting),” they are embracing—and in Bois’s case simultaneously contending with—what Isaiah Berlin described as the perils of “historical inevitability.” Certain of Matisse’s works—the Fauve landscapes, The Red Studio (1911), the Shchukin and Barnes Dances, and the final paper cutouts—are seen by many of his admirers as fulfilling a historical imperative. They are not so much individual statements as they are contributions to a larger historical drama, involving the steady, inevitable dissolution of the self-enclosed, illusionistic world of easel painting.

For those who embrace this evolutionary model, much of Matisse’s work of the 1920s can appear reactionary, as if the artist were taking a stand against art’s inevitable forward flow. Matisse, by this logic, was rejecting precisely what Berlin condemns as “impersonal or ‘trans-personal’ or ‘super-personal’ entities or ‘forces’”—and thereby revealing, at least to Bois’s way of thinking, his lack of relevance or significance. Judged by these standards, Matisse’s development becomes a conundrum. At times he is in the stream of history, at other times apart from it. For those who want to align Matisse with the triumph of abstraction, his last major text, published to accompany a book of his portraits, can be an embarrassment. In this essay he focuses on the importance of achieving a likeness of the sitter, and praises the verisimilitude of the Renaissance masters Holbein, Dürer, and Cranach. The apostle of abstraction ends his life with an exploration of the enigmas of appearance.

In his studies of The Dance Bois pursues themes from his earlier essay “Matisse and ‘Arche-drawing,’” which focuses in part on another major work at the Barnes, Le Bonheur de vivre (1905–1906). In the background of Matisse’s Arcadian vision there is a circle of dancers that prefigures The Dance, while the foreground is dominated by languorous nudes, women and men dreaming their dreams. The argument of “Matisse and ‘Arche-drawing’” is that in Matisse’s greatest work the function of line is not so much to make form as to measure or delimit areas of flat space. This leads to what Bois dubs the “quantity-quality equation,” whereby the arrangement of areas of color across the canvas fuels the “all-over nature of Matisse’s best works.” The virtue of all-over painting, as Bois sees it, is that each area is accorded if not an equal then a commensurate value. This arguably “democratic” approach to composition is embraced as a rejection of older “hierarchical” systems, whereby (to give but one example) the figure of Saint Jerome is accorded more visual significance than the surrounding landscape.

It is clear why a painting such as Moorish Woman holds far less interest for Bois, rejecting as it does the all-over effect in favor of a layering and knitting-together of variegated patterns and tonalities, with the figure’s imposing head and torso having a central, stabilizing force. Bois favors those Matisse canvases that he believes are “tensed to a maximum, like the membrane of a lung ready to explode.” But doesn’t Moorish Woman have its own kind of tension, albeit an inward-turning tension? Bock-Weiss believes that Matisse’s work of the 1920s is interesting particularly for its exploration of “instinct,” for a rejection of “essential qualities, universal values, or timeless verities,” and perhaps also for a search for “modernist origins,” meaning the spirit of Courbet, Renoir, and Manet. And why not? Couldn’t an art that wound back have its own inalienable virtues, as convincing in their way as those of The Dance?

Visitors to “Graphic Passion: Matisse and the Book Arts,” at the Morgan Library and Museum, were able to explore precisely those ambiguous byways of Matisse’s imagination. While a couple of Matisse’s book projects—the illustrations for Mallarmé’s poems (done at the same time as the Barnes mural and discussed by Bois) and the portfolio Jazz—have been widely admired, the full range of his involvement with literary sources and the literary imagination has been underappreciated.

The Morgan exhibition was based on the collection of Frances and Michael Baylson, who have acquired not only Matisse’s most luxurious illustrated books, but also more casual and informal works, to which he occasionally contributed vigorous portraits of literary friends. These images highlight gifts for naturalistic or hyperbolic characterization that some may be surprised to find coming from the hand of an artist often praised for his ability to be succinct on a grand scale. Matisse sometimes seemed to take as much interest in the smallest rococo amusement as in the largest austere decoration. In a 1946 essay, “How I Made My Books,” he observed, “I do not distinguish between the construction of a book and that of a painting, and I always proceed from the simple to the complex, yet am always ready to reconceive in simplicity.”

Writers who believe that their preferred artistic ideas or ideals are ratified by history have a built-in rhetorical advantage. Bois’s standing among art historians has much to do with his ability to convince his colleagues that history is on his side. He has not worked alone, aligned as he is with Rosalind Krauss and others who have been important contributors to October, the scholarly journal that has consistently argued for a theoretical approach to the history of art. Back in 1996, Bois and Krauss joined forces to organize an exhibition at the Pompidou Center in Paris entitled “L’Informe: Mode d’emploi.” It was their riposte to Greenberg’s formalism, their declaration of the next stage in art’s evolutionary drama. In the accompanying book, published in English in 1997 as Formless: A User’s Guide, Bois began with the renegade Surrealist Georges Bataille and his interest in Manet. Bois proposed, in prose that is as aggressive as it is opaque, that modernism now be “grasped against the grain,” that modernism “start…shaking,” with purity replaced by impurity, an embrace of “the scatological dimension of base materialism,” and “a disavowal of modernist sublimation.”

Together with two other colleagues—Hal Foster and Benjamin H.D. Buchloh—Bois and Krauss produced in 2004 a vast text, Art Since 1900, which is a catechism of their historical preferences and prejudices. In an incisive critique published in The Times Literary Supplement, the English painter and writer Timothy Hyman observed that this 704-page book presents “a twentieth century without, say, a Max Beckmann triptych or a Bonnard self-portrait; where Douanier Rousseau and early Chagall both go unillustrated; where Balthus and Edward Hopper remain resolutely unmentioned.” What doesn’t fit with their historical scheme might just as well not exist.

When taste is shaped by a faith in historical inevitability, facts tend to be interpreted in particular ways, to make sure they accord with the theory. And when the theory begins to pale, a new theory is promptly invoked, so that in Bois’s “Painting: The Task of Mourning” all the old talk about the death of painting is reinvigorated with a bit of game theory, the argument being that modern painting, as a “specific performance” of the game of painting, can die, while “the generic game” of painting can probably proceed. Bois performs these theoretical operations with considerable delicacy when he is dealing with specific artists, not only in his writings on Matisse but also in his writings on Ellsworth Kelly. Although Matisse does not figure significantly in Bois’s texts for the first volume of the Ellsworth Kelly catalogue raisonné, there can be little question that Matisse’s cut-paper compositions of the late 1940s and early 1950s had a profound impact on Kelly.

Kelly’s work in the years around 1950 is austere and hard-edged, with enigmatic images derived through operations of chance and from fragmentary elements of cityscape or landscape. It has long been known, to give but one example, that the several versions of Kelly’s painting La Combe are related to a photograph of shadows on stairs at the Villa La Combe, in the town of Meschers where he spent August 1950. There is something moving about the preternatural powers of concentration Bois brings to his studies of this artist who means so much to him. The catalogue raisonné also happens to be one of the most beautifully produced volumes of recent years.

Writing about both Kelly and Matisse, Bois proceeds deliberately. Some readers will be left with the impression that no stone has been left unturned. But Bois turns over only the stones that serve his purpose, whether consciously or not so consciously I cannot say. He is perfectly justified in emphasizing Kelly’s interest in randomness and chance, in what he refers to as “the Ariadne’s thread of non-compositionality linking almost all the works he produced in France.” But in his haste to establish Kelly’s originality—and perhaps link Kelly’s elegantly ascetic art with his own penchant for “formlessness”—Bois downgrades, disputes, and willfully ignores the extent to which Kelly’s work was shaped by a European fascination with geometric and constructivist art that had begun in the 1920s and was flourishing after World War II.

Bois may find it simplistic or reductionist to too closely associate Kelly’s clean-lined, stripped-down compositions with works by Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg, Georges Vantongerloo, Auguste Herbin, Alberto Magnelli, Max Bill, and Richard Paul Lohse. But in his insistence on opposing what he sees as Kelly’s revolt against traditional composition with a European tradition of utopian or idealist compositional strategies, Bois strikes me as missing a profound commonality, a shared sensibility. (Kelly himself, at least in his later years, wanted to dismiss or at least downgrade some of these associations, which helps clarify the artist’s embrace of Bois’s brand of art history.)

Bois, with his taste for historical imperatives, is all too insistent on establishing Kelly’s unique position as a pioneer of noncomposition or anticomposition. He cannot overlook Kelly’s friendly interactions with Jean Arp and his familiarity with the geometric compositions of Arp’s wife Sophie Taeuber-Arp, but he seems to want to free Kelly from their strong influence. I think he misses the mysterious synergy between Dadaism and Constructivism that informed the achievements of Arp, Taeuber-Arp, Kurt Schwitters, and van Doesburg in the years during and after World War I, a convergence of opposites that helped shape Kelly’s aesthetic.

As for Kelly’s improvisational use of full-strength color, it is not so far from the wonderfully playful, anything-can-go-anywhere use of color in works by Fernand Léger and Alexander Calder that Kelly would have been seeing during his years in Paris. Nor can Matisse’s cutouts be ignored. But Bois chooses not to focus on these associations, perhaps because they show Kelly glancing backward or sideways, which is not something he is eager to consider. (In 2014 Kelly curated a show of Matisse drawings at Mount Holyoke College.)

Bois may conceive of his close-grained writings on Kelly and Matisse as case studies in the modern artist’s heroic escape from the constraints of older pictorial structures and ideas. But an artist only appears to engage him as long as he is heading toward Bois’s preferred goal. Looking at some of Matisse’s work after the completion of the Barnes mural—charcoal portraits of the collectors Etta and Claribel Cone and the vigorous quotidian poetry of a painting entitled Interior with Dog—Bois accuses the artist of “a certain amount of backpedaling,” of “some ambivalence, one might even say nostalgia.” Bois does not care for what he refers to as “the traditional modeling and shading of the Cone portraits.” He feels they lack “the allover energy” that he admires in Matisse’s work. I am left wondering if he isn’t simply exposing the limits of his own taste. What is at stake here is much more than one man’s taste. What is at stake is the historian’s willingness to accept the freedom of the artistic imagination—to embrace Matisse’s multitudinousness.

Matisse was obviously a very complicated man, and different commentators will quite naturally reveal different sides of his personality. The slightly clinical tone of Bois’s writings is true to a coolness in Matisse’s makeup. Bois sees Matisse as a methodical, deliberate artist, and there is no question that he was. But it can be instructive to turn from Bois’s account of the Barnes mural to the pages in Hilary Spurling’s brilliant biography of Matisse that deal with the same period.2 In Spurling’s account, Bois’s cool customer gives way to a more robust, convivial figure, his labors on the mural mingled with his eager friendship with the younger Surrealist painter André Masson.

Spurling gives to the story of Matisse’s work at the Barnes some of the hurried-up, carousing pace of a novel by Thackeray or Trollope. Bois might put this down to the limitations of the English author’s biographical imagination. Then again, Matisse, who was born in 1869, was in some sense a man of the nineteenth century—he had an intense interest in and affection for the work of Renoir—and a careful biographer might accuse Bois of forcing him too much into the mold of Left Bank philosophizing at its most megalomaniacal and austere.

Need we choose between Spurling and Bois? Certainly each author’s account of Matisse and the Barnes mural is illuminating in its own way. The trouble with Yve-Alain Bois is that he is all too sure that history is on his side, and is therefore disinclined to consider aspects of Matisse that might violate his preferred historical scheme. Bois has lost sight of what Isaiah Berlin referred to as “the crooked timber of humanity.” Berlin was quoting Kant, who said that out of such material “no straight thing was ever made.” There is no career in modern art with more startling twists and turns than Matisse’s. One day he seems to stand with the revolutionaries, the next he is almost a conservative. To straighten all this out is to deny Matisse what finally binds us to him, which is his vexatious humanity.