In Flaubert’s Parrot (1984), his best-known novel, Julian Barnes recounts the scene in L’Éducation sentimentale where Frédéric, its hero, “wanders through an area of Paris wrecked by the 1848 uprising” and notices “amid the chaos” things that have survived by chance:

He sees a clock, some prints—and a parrot’s perch. It isn’t so different, the way we wander through the past. Lost, disordered, fearful, we follow what signs there remain; we read the street names, but cannot be confident where we are. All around is wreckage.

The scene is reminiscent of The Noise of Time, Osip Mandelstam’s prose work of 1925, from which the title of Barnes’s latest novel is, it seems, derived. The problem of remembering across the void of revolution is the Russian poet’s theme:

Where for happy generations the epic speaks in hexameters and chronicles I have merely the sign of the hiatus, and between me and the age there lies a pit, a moat, filled with clamorous time, the place where a family and reminiscences of a family ought to have been.

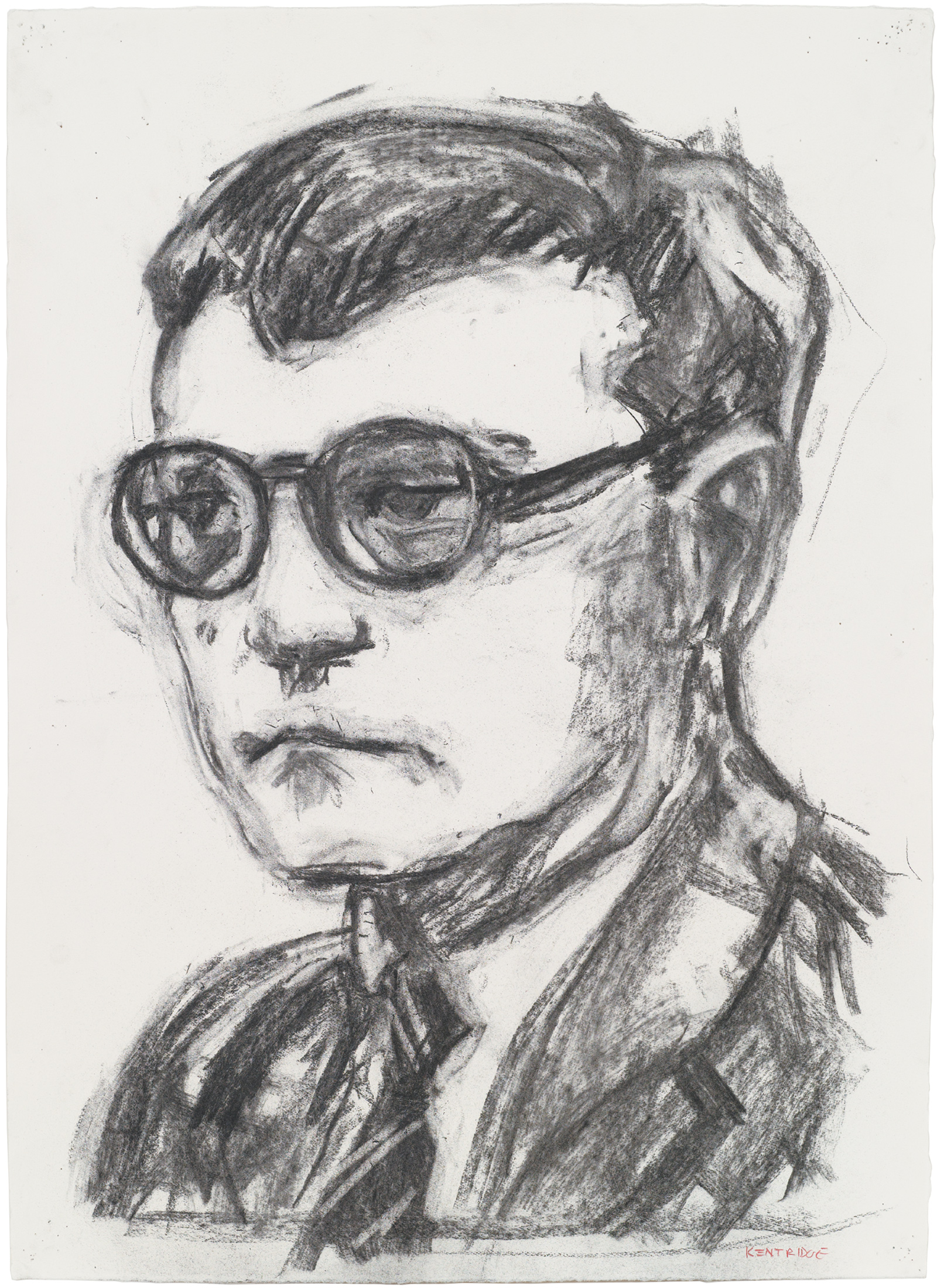

The Soviet composer Dmitri Shostakovich is the man remembering in Barnes’s The Noise of Time, a novel that, like Flaubert’s Parrot, mixes fiction and biography, memory and myth. Much of Barnes’s most successful work is biographical, combining documented facts with literary invention in novels such as the Booker-shortlisted Arthur and George (2005), and he has returned to something like this form in The Noise of Time, his first novel since winning the Booker Prize with The Sense of an Ending in 2011. Memory is at the heart of it. Shostakovich, as Barnes imagines him, takes stock of his life, which has been wrecked by Stalin’s revolution, and finds redemption in the music that emerges from the noise of time. But unlike Flaubert’s Parrot, which revels in the impossibility of ever reconstructing a biography, The Noise of Time makes just that claim. In it Barnes assumes a knowingness about the private thoughts and emotions of Shostakovich, a knowledge largely based on memoirs about him, and asks us to believe that he is taking us inside his head. As a novel-reader I am willing to believe him; as a historian I am not.

Like Flaubert, Shostakovich was resistant to reflecting on his own biography. Introverted, even secretive, shy and anxious by nature, he was hostile to the idea of writing reminiscences. He revealed himself entirely in his music and saw no need to write memoirs. He was also famous for inventing tales about himself—just for the sake of a good story or a laugh. As Barnes recounts, there are at least three versions of a story he told many times about being in the crowd to welcome Lenin at the Finland Station on April 3, 1917 (when Shostakovich was only ten years old). In one version he had gone along with a group of school friends, and in another with his Bolshevik uncle Maxim Kostrikin.

But there was a third possibility: that he had not seen Lenin at all, and been nowhere near the station. He might just have adopted a schoolfellow’s report of the event as his own. These days, he no longer knew which version to trust. Had he really, truly, been at the Finland Station? Well, he lies like an eyewitness, as the saying goes.

The Noise of Time is full of half-remembered incidents, episodes that may, or may not, have taken place. The mode of remembering is interior monologue, a conversation between Shostakovich and his conscience, looking back on the decisive moments of his life when he was attacked by the Soviet regime or forced to compromise his principles. But the timing of the monologue remains unclear; it floats free from recorded dates, and it is delivered in the third person, which creates a powerful effect of distancing. Perhaps the technique is intended to reflect the alienation many people felt from their public selves (necessary masks to display their political conformity) in the Soviet Union.

The novel begins with a half-forgotten and imaginary scene from the war years in which three men, a legless beggar and two travelers, drink a vodka toast on a station platform, the significance of which will be revealed only at the end. As they chink their glasses, “the nervous fellow put his head on one side—the early-morning sun flashing briefly on his spectacles—and murmured a remark; his friend laughed.” The incident is soon forgotten by the “one with spectacles.” At a later point he cannot even recall if they gave the beggar sausage or a few kopecks. But it is not forgotten by his companion, who is, we are told in a manner to suggest that he might be the mysterious narrator, “only at the start of his remembering.”

Advertisement

Barnes is a great novelist and the writing in the early pages is magnificent. From the disjointed fragments of the opening paragraphs, the reader has the confidence of being in the hands of a master storyteller, knowing that these images will all return with symbolic significance:

All he knew was that this was the worst time.

He had been standing by the lift for three hours. He was on his fifth cigarette, and his mind was skittering.

Faces, names, memories. Cut peat weighing down his hand. Swedish water birds flickering above his head. Fields of sunflowers. The smell of carnation oil. The warm, sweet smell of Nita coming off the tennis court. Sweat oozing from a widow’s peak. Faces, names.

The faces and names of the dead, too.

Shostakovich emerges slowly from this quasi-Cubist montage of images and names. He is the terrified and ghost-like figure standing on the landing by the lift, smoking nervously, waiting with his suitcase in the middle of the night for the NKVD men to come for him, so that at least if they arrest him, his wife and daughter will not be disturbed. The year is 1936, a leap year, sometime after the attack on Shostakovich’s until-then-successful opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk in a Pravda editorial (“Muddle Instead of Music”) on January 28. Two days previously, Stalin and his entourage of Politburo leaders had walked out of a performance of it at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow. The vicious editorial, which must have been initiated, if not written, by Stalin, encouraged numerous denunciations of Shostakovich as a “formalist” and “enemy of the people”—in those days a warning sign of imminent arrest—not only by officials in the Party press but also by composers envious of his success.

Arrest did not come, but in an episode recounted in The Noise of Time Shostakovich was summoned to the “Big House,” the NKVD headquarters in Leningrad, after the arrest of Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky, an old family friend and patron, in the Great Terror. Urged by his interrogator to confess to talks with Tukhachevsky about politics, Shostakovich was given a weekend to recall every detail of the marshal’s “plot” to kill Stalin; but on the Monday, when he reappeared at the Big House, certain of his arrest as a witness to this “plot,” he was told by the guard on duty that he could go home: his interrogator had himself fallen victim to the Great Terror and had been arrested during the weekend.

This is the first of three “Conversations with Power,” in 1936, 1948, and 1960, a triad of leap years, around which the novel is structured. If the first encounter is defined by fear, the next two chart the composer’s compromise with the regime, his growing dread of it, and his capitulation to the demands it made of him.

In February 1948, Shostakovich was included on a blacklist of composers (along with Aram Khachaturian and Sergei Prokofiev) charged by the authorities with writing music that was “formalist” and “alien to the Soviet people and its artistic taste.” Banned from the Soviet concert repertoire and dismissed from the Conservatory, Shostakovich was reduced to a terrible state, on the verge of suicide, according to his friends. In March 1949, the ban was lifted by Stalin, who thus persuaded Shostakovich to attend a Congress for World Peace in New York, where in Barnes’s brilliant retelling he parroted a speech prepared for him condemning the composers of the West “who believed in the doctrine of art for art’s sake, rather than art for the sake of the masses” and then “heard himself” attack the work of Igor Stravinsky, his own musical hero, whom he denounced as a traitor to his native land.

Interrogated by the émigré composer Nicolas Nabokov, who set out to expose the sham, Shostakovich was humiliated in a scene reminiscent of the Show Trials: on each point of the text that he had just delivered, Shostakovich was asked by Nabokov, in the role of a public prosecutor, “Do you personally subscribe to the views expressed in your speech today?” Poor Shostakovich. He was forced to say he did. “The supposed author of these words sat there motionless and unreacting, while inside he felt awash with shame and self-contempt.” On the long flight back to Moscow, courtesy of American Overseas Airlines, he drowns his sorrows in Scotch and soda.

The third section of the novel focuses on the events of 1960, when Shostakovich relented under pressure and finally agreed to join the Communist Party. As Barnes has Shostakovich recount it, this was “his final, and most ruinous Conversation with Power,” as represented by the Central Committee official Pyotr Pospelov, in part because, as he pleads with Pospelov in a desperate attempt to avoid enlistment, “it has been one of the fundamental principles of my life, that I would never join a party which kills,” and in part because by joining the Party he let himself be used as its puppet, signing statements written for him by the Party in his name, thereby losing much of his integrity and the respect of many of his friends.

Advertisement

The various factors that led him to capitulate are not fully represented in The Noise of Time, in which the monologue is dominated by a discussion of cowardice, the loss of integrity, self-loathing, and moral suicide, much of which is drawn from things he said to friends around that time. But there is no mention in the novel of the impact of his wife’s death in 1954, followed by the death of his domineering mother in 1955, which left him feeling vulnerable and frightened for his children, according to his closest friends; nor is there any account of the fact that Shostakovich was worn down by a debilitating illness in his hands and legs, which meant long stays in hospitals after 1958.

The human frailties of Shostakovich are overshadowed by the moral questions Barnes imposes on him. It was part of the composer’s nature not to be able to say “No” to anyone. “When somebody starts pestering me,” he told his friends, “I have only one thought in my mind—get rid of him as quickly as possible, and to achieve that I am prepared to sign anything.” Perhaps Shostakovich simply wanted to be left alone to write music, and if that meant he had to join the Party, it was a price he was prepared to pay. It was only later, in the early 1970s, when, terminally ill, he put his name to official letters denouncing Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Andrei Sakharov that his membership assumed the moral weight that Barnes gives it from the start. And even then it carried such significance only in the eyes of the dissident and semidissident intelligentsia, for whom the artist had a duty of moral leadership.

Most of the anecdotes and quotations in The Noise of Time come, as Barnes acknowledges, from Elizabeth Wilson’s superb oral history, Shostakovich: A Life Remembered (1994), an anthology of interviews and reminiscences about the composer by his friends. There are whole pages of The Noise of Time reproduced as fiction from Wilson’s documentary account. More problematically, Barnes has also drawn from the controversial book by Solomon Volkov, Testimony (1979), published four years after the composer’s death and presented to the world as “The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich,” which is seen by many scholars as a fabrication, even if there is some truth in it.* In Volkov’s semifictional account Shostakovich appears as a lifelong opponent of the Soviet regime, a secret dissident, and a teller of the truth through coded messages in his music.

Barnes has a good sense of what life was like in the Soviet Union. He captures well the black humor, irony, and cynicism that pervaded the intelligentsia circles in which Shostakovich moved—a mood created perfectly by the opening sentence of each section, practically identical in 1936, 1948, and 1960: “All he knew was that this was the worst time.” There are small errors: “cosmopolitanism” was not an accusation much used against artists before the 1940s; and when the poet Anna Akhmatova referred to the “vegetarian years” she meant the 1930s, before the meat-eating Terror of 1937, not the later years of Khrushchev’s Thaw. But I hesitate to point such errors out because they hardly matter in a work of imaginative literature. I would not want to share the destiny of the academic pedant Dr. Enid Starkie, ridiculed by Barnes in Flaubert’s Parrot for claiming there were minor inconsistencies in the color Flaubert gave to Emma Bovary’s eyes.

The Noise of Time is also very good on the composer’s character—nervous and neurotic, at times hysterical, using threats of suicide to escape his mother’s tyranny when he was young, drinking heavily in his last years to overcome his self-loathing and lift his feelings of oppression by the state. It is less good on his music, which is strangely absent from the book, although it refers to many sounds—“chiming clocks” and “four blasts from a factory siren in F sharp” that went into Shostakovich’s Second Symphony. The reader unaware of the composer’s music would not get a sense of it from the novel, nor an understanding of its emotional importance to Soviet people at the time.

Akhmatova spoke for them in 1957 when she wrote “Music (Dedicated to Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich),” after hearing his Eleventh Symphony (The Year 1905), a composition filled with quotations from revolutionary songs that voiced the people’s suffering and hopes of freedom, which she compared to “white birds flying against a terrible black sky”:

It shines with a miraculous light

Revealing to the eye the cutting of facets.

It alone speaks to me

When others are too scared to come near.

When the last friend turned his back

It was with me in my grave

As if a thunderstorm sang

Or all the flowers spoke.

The real problem of the novel, however, is not one of music but of voice. Whose is speaking in this book? The Shostakovich character or Barnes himself? The two are sometimes hard to tell apart. What about the real Shostakovich? Does it matter if his words are changed in meaning to suit Barnes’s purposes? Let us take one example. In 1936, after the attack on Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, Shostakovich wrote to Andrei Balanchivadze, one of the few Soviet composers to support him, expressing his opinions about the pressure he was under to renounce his work:

One must have the courage not only to kill one’s work, but to defend them. As it would be futile and impossible to do the latter, I am taking no steps in this direction. In any case, I am doing much hard thinking about all that has happened. Honesty is what is important. Will I have enough in store to last for long, I wonder? But if you ever learn that I have “disassociated” myself from Lady Macbeth, you will know that I have done so 100 per cent. I doubt that this will happen soon, however. I am a ponderous thinker and am very honest in all that concerns composition.

In The Noise of Time this becomes the following:

He found himself reflecting on questions of honesty. Personal honesty, artistic honesty. How they were connected, if indeed they were. And how much of this virtue anyone had, and how long that store would last. He had told friends that if ever he repudiated Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, they were to conclude that he had run out of honesty.

Barnes returns to the question of personal and artistic honesty in several later passages. It is the main idea in the novel. But it is far from clear if Shostakovich ever thought about these questions in this way. In his letter to Balanchivadze, the composer does not say anything about personal honesty or make a connection between it and artistic honesty. He is speaking of artistic honesty, and says that, if he does repudiate Lady Macbeth, it will be an honest act of repudiation, the result of long and ponderous thought. He is full of doubts but not courage. Barnes’s Shostakovich is by contrast defiant, a Volkovian dissident who would never honestly renounce his opera. He tells his friends that if he ever does, they should know that he is being insincere (in other words, that he was forced to do so by powerful pressure).

Maybe none of this matters. The Noise of Time is a novel. Artistic truth is a different sort of truth than that aimed at by biographers or historians, and it follows different rules. As a novelist, Barnes can do what he wants with Shostakovich; he can put whatever words he wants into his mouth. But who, then, is the Shostakovich in The Noise of Time? Is he no more than a puppet whose strings are pulled by Barnes? A mouthpiece or parrot for his discourse on the artist’s honesty?

The novel ends where it began, with the three drinkers chinking glasses, filled to different levels with vodka, and Shostakovich, the “one with spectacles,” hearing in the chink of glasses a perfect triad—“a sound that rang clear of the noise of time.” It is a beautiful motif, which sums up the composer’s hope that his music might redeem the moral wreckage of his life. But it is only a literary motif. It did not happen in reality.

-

*

See my “The Truth About Shostakovich,” The New York Review, June 10, 2004. ↩