1.

Of the self-styled “progressive” liberal arts colleges founded between the world wars—including Bennington and Sarah Lawrence, Goddard and a reconceived Antioch—Black Mountain College was among the most distinctive, and was also the first to close. A fragile undertaking from the start, rendered more precarious by the Great Depression, the college was established in 1933, with ten faculty members and nineteen students, on a rented estate in the mountains of North Carolina that featured a central building in the antebellum style called (lest students forget they were in the old, still-segregated South) Robert E. Lee Hall. A breakaway faction of faculty from Rollins College in Florida, under the leadership of a renegade classicist named John Rice, was eager to apply John Dewey’s “learn by doing” principles to higher education. Dewey himself visited the college in 1935 and approved of what he saw. “The College exists,” he told Rice, “at the very ‘grass roots’ of a democratic way of life.”

Black Mountain College was always tiny—with around sixty students in its short-lived prime and averaging no more than forty—always poor, and frequently, if democratically, fractious. There was no external board of trustees, no paid administrative staff. Faculty and students lived and worked together, in close quarters, and made decisions by the Quaker practice of achieving consensus rather than voting.

During its final years, before it closed in 1957, Black Mountain could hardly be called a college at all, resembling instead a ramshackle artists’ and writers’ collective assembled around its final rector, the charismatic poet and Melville scholar Charles Olson, who sold off the college’s land and buildings piecemeal to keep the dream—whatever that dream had become—alive, while publishing the influential Black Mountain Review, featuring poetry by “Black Mountain Poets” Robert Creeley, Denise Levertov, and Robert Duncan, to the end. “Why shouldn’t things stop when they’re over?” Olson asked, reasonably enough.

The romance of dying young would seem to extend, in this case, to educational institutions, as a wide-ranging exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in Boston is the latest reminder. Few American schools have attracted the sustained and impassioned attention accorded to Black Mountain College, and especially to the many well-known artists who worked there: Willem de Kooning, Jacob Lawrence, Robert Motherwell, John Cage, and Merce Cunningham among its teachers and, among its students, Robert Rauschenberg, Ruth Asawa, and Cy Twombly. The innovative curriculum at Black Mountain (no grades, no required courses, no standard exams) was always centered around its arts program, run by the German émigré artist Josef Albers from its inception, before he decamped to Yale, amid one of the schisms that periodically roiled the school, in 1950.

Albers had been a master teacher at the Bauhaus, the design academy shut down by Hitler in 1933, which had also been inspired in part by Dewey’s notion of “art as experience.” In his classes at Black Mountain, Albers—who knew little English and at first relied on his wife, the textile artist Anni Albers (my grandmother’s older sister), to translate for him—set a tone of demanding “trial-and-error experience” and relentless experimentation. What he taught, primarily, was the nature of artistic illusion, challenging students to explore the relativity (or “interaction”) of color—how colors can be made to change their appearance when juxtaposed with other colors—and the ways in which one material can be made to resemble another. “A good swindle,” he would say—or perhaps Schwindel, the German word for vertigo—when confronted with marbles made to look like fish eggs, or a brick resembling a loaf of bread.

As Albers scholar Brenda Danilowitz notes, in an article written for a concurrent exhibition on Albers and color at the Mead Museum at Amherst College:

For Albers, teaching and learning were not a matter of the teacher imparting privileged information and the student acquiring received knowledge. Teaching involved asking questions, not providing answers; and Albers always privileged learning over teaching.

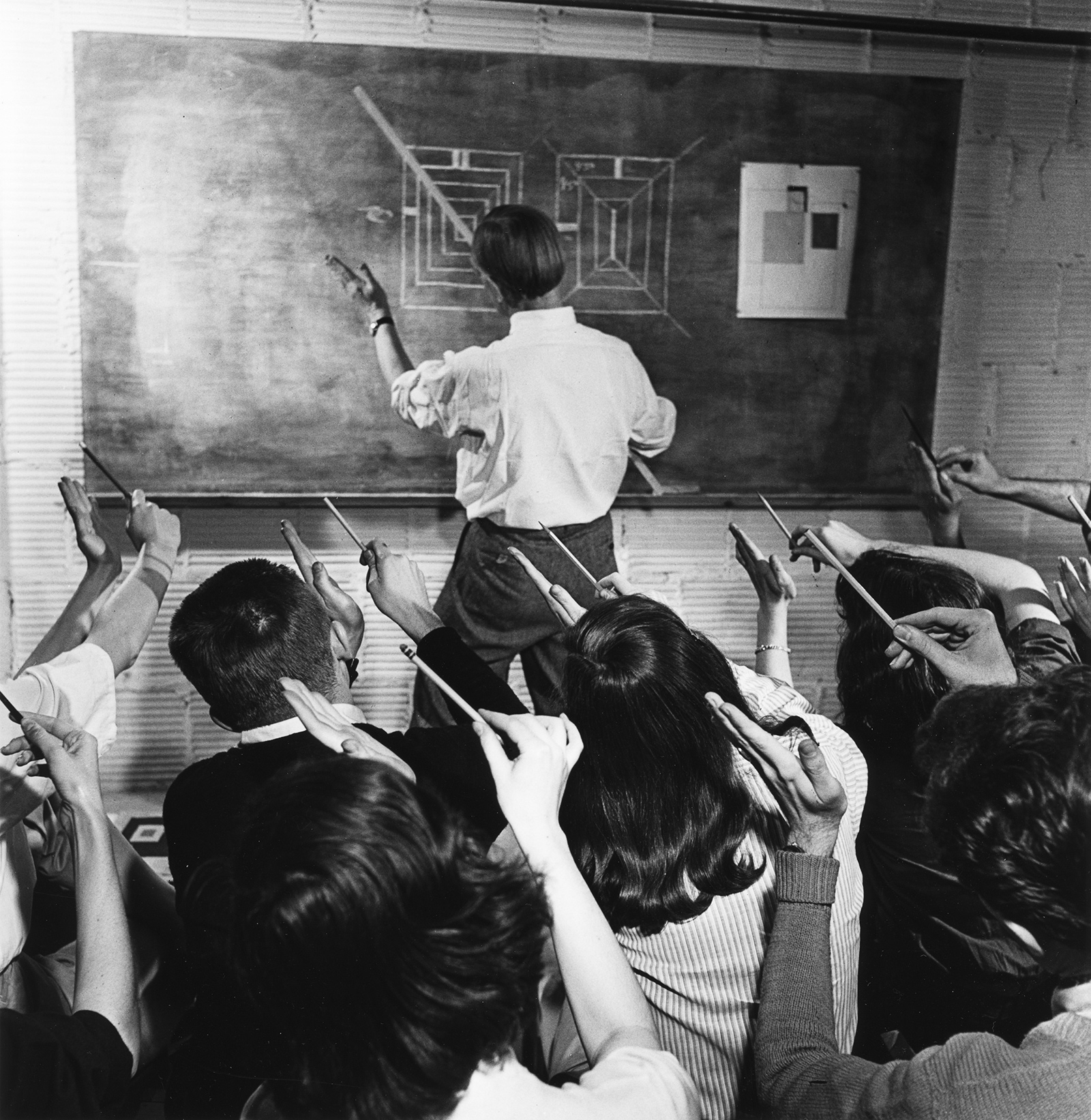

Vivid photographs of Albers teaching make him resemble a kindergarten teacher—down on his knees adjusting colored paper, or guiding a student’s hand in a drawing class—rather than a traditional lecturer. Albers seems to have inspired other teachers at the college, many of whom attended his design classes, to teach in similarly rigorous, experience-based ways, not only in the arts but in other traditional subjects of the liberal arts, such as mathematics and biology.

Much else about the school was distinctive. As Bryan Barcena, an ICA curatorial assistant, notes, it was “the first all-white Southern college to admit a black student, a full decade before Brown v. Board of Education.” Albers invited the African-American painter Jacob Lawrence to teach at Black Mountain during the summer of 1946. Lawrence painted his marvelous Watchmaker at the college in his “carpenter Cubism” style, exploiting unexpected color combinations—the blue and white stripes of the black artisan’s shirt juxtaposed with his brown work table—familiar from Albers’s teachings (which Lawrence gratefully acknowledged) for this striking homage to meticulous craftsmanship.

Advertisement

Students and faculty also testified to the relative tolerance of the school on sexual matters. As the New York School abstract painter Jack Tworkov reported in 1952:

These people are willing to take the consequences of what they preach—which is most unusual. In essence there exists the utmost freedom for people to be what they please. There is simply no pattern of behavior, no criteria to live up to. People study what they please, as long as they want to, idle if they want to, graduate whenever they are willing to stand on examination, even after only a month here, or a year, or whatever, or they can waive all examinations, and graduations. They can attend classes, or stay away. They can work entirely by themselves, or they need not work whatever. They can be male, female, or fairy, married, single, or live in illicit love. The instructors can hold classes or tutor individually, meet their classes as often or as little as they want to. Yet much work is being done here.

2.

In recent decades, there have been several exhibitions—in Spain, England, and, earlier this year, Berlin—devoted to the legacy of Black Mountain, amid evidence that the school has attracted a new generation of committed scholars. The Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center—located in Asheville, a few miles from the original site of the college—recently received funding for an expansion of its exhibition space and popular public programs. And recently, the ICA—an architecturally striking museum located right on the Boston waterfront, and committed to the very latest developments in art—mounted an ambitious exhibition, the largest in its history, devoted to a college defunct for nearly sixty years, which is traveling to Los Angeles and Columbus, Ohio.

Much about the show seems to point to the essentially transitory nature of Black Mountain College itself. Its title, “Leap Before You Look,” which could be mistaken for one of John Cage’s Zen-like injunctions but actually comes from a poem by W.H. Auden, hardly seems sound advice for planning a college. In its first, provisional phase, Black Mountain College had to vacate its rented buildings at the Blue Ridge Assembly each summer. When the college, through generous donations, acquired a large property around the utopian-sounding Lake Eden nearby, in 1937, it commissioned the Bauhaus architects Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer to design a complex of academic buildings near the lake. When their plan proved too expensive, students and faculty laboriously built a scaled-down studies building, which recalls the Bauhaus in its austere, form-follows-function design. “For the next four years,” as David Silver observes in his interesting article on the college’s work program and farm, “Black Mountain functioned as a mobile campus—renting, living, and holding classes at Blue Ridge and then, in the afternoon, loading up the farm truck and driving to Lake Eden to insulate existing buildings and construct new ones.”

Some of that mobility and can-do attitude gets into the wonderful work by students and young instructors on display in the exhibition. Ceramicist Peter Voulkos’s antic Rocking Pot, bristling with blades and punctured holes, seems pitched to roll right out of its display case. Ruth Asawa’s hanging wire vessels, inspired by Mexican basketry, have a swaying biomorphic quality inspired, in part, by her dance classes with Merce Cunningham. Robert Rauschenberg’s bizarre portable room, part stage set for a Cunningham dance named Minutiae and part freestanding sculpture, constructed of paper, fabric, newsprint, wood, metal, plastic, and oil paint, looks like something a student might make after a day of driving nails, aligning walls, and driving the trash truck (Rauschenberg’s student job).

With support from the GI Bill, which brought students like Rauschenberg to campus, the college thrived briefly after World War II, helping to support itself with its popular summer institutes. These summer sessions, a significant part of the legacy and legend of Black Mountain, were really evanescent schools of their own, temporary assemblages of talent deeply involved in shared projects—the music of Schoenberg, say, or Japanese folk pottery—for a few weeks or months, only to be dispersed. As Silver notes, the summer sessions, so vital to day-to-day finances, also helped spell the doom of the college’s work program and farm, since “so many of the summer instructors were visitors” and “were not schooled in the community spirit of the campus.”

3.

The cover design for the ICA’s exhibition catalog features one of Josef Albers’s arresting collages combining paint and autumn leaves, another suggestion that whatever was achieved at Black Mountain was evanescent. Fall leaves seem to have constituted something of a cult at Black Mountain, surrounded by the stunning foliage of the Appalachian Blue Ridge. “Nowhere in the world, it seems to us, is the autumn foliage as brilliant in color as in the United States,” Albers wrote in a section of his seminal textbook Interaction of Color. “When leaves are collected, pressed, and dried—eventually varnished, even bleached, and sometimes also dyed or painted—they provide a most welcome enrichment of any color paper collection.”

Advertisement

Albers’s leaf studies have a lilt and lyricism harder to see in his more familiar geometric abstractions, such as his famous Homage to the Square series, begun after his departure from Black Mountain. The ICA example is frontal and flat, with an upright leaf of a tulip tree, its arms seemingly extended in welcome, surrounded by upward- and downward-facing oak leaves. The drama here, of a Shaker-like austerity, is in shifting figure and ground, a frequent emphasis in Albers’s classes. Striking leaf studies in the Amherst show look more like dancers on a proscenium stage; two more tulip tree leaves, given illusionistic depth with black and white paint, perform a pas de deux out of Magritte. A leaf study by Albers’s student Ruth Asawa, which circles the leaves with a meandering coil of wire (prefiguring her later constructions of crocheted wire), is complemented at the ICA by a photograph of a student dressed for a costume party in 1949, clothed in nothing but leaves.

“Ephemeralization” was what Buckminster Fuller, a Black Mountain regular as adept at inventing words as structures, called such practices of “doing more with less.” Ephemera, an aesthetic of found objects and picked-up pieces, seem to have dominated the curriculum at Black Mountain, both as a creative response to what Helen Molesworth, the former chief ICA curator who organized the show, refers to as the Depression-era “culture of scarcity” at the college—fallen leaves are cheaper than colored paper—and as an ethos shared by many of the young artists attracted by the place. The Alberses, who spent their summers in Mexico, were attuned to the unexpected possibilities of humble materials like the paper clips and plumbing washers that Anni Albers and Alexander Reed used to construct jewelry, or the discarded wire that Asawa learned to crochet. “It also taught us,” Anni Albers wrote, “that a society need not be prosperous to produce great art. In fact, one wonders if the reverse is not true.”

Invited by Albers, Fuller arrived at Black Mountain in his three-wheel motor home for the summer session of 1948. Fuller quickly involved students and faculty in the attempt to erect his first geodesic dome, another experiment in ephemeralization, using, as it turned out, overly flexible venetian-blind materials. Photographs of the occasion look like the erecting of a maypole, with the mercurial Fuller—“Bucky’s eyes…had us all mesmerized,” student Elaine de Kooning remembered—as master of revels. Much the same cast reassembled for Cage’s production of Erik Satie’s play The Ruse of Medusa, with Fuller, de Kooning, and Merce Cunningham in starring roles.

4.

So fleeting was the initial impression left by another production now referred to as Theater Piece No. 1, the best-known event in the history of the college, and regarded as the first “happening”—a simultaneous performance of unrelated and partially improvised activities—that it can only be reconstructed by memory. At a school where everything of significance seems to have been photographed, by Albers and Rauschenberg as well as by former student turned instructor Hazel Larson Archer, not a single photograph survives of the occasion; even the exact date, on an evening in August 1952, remains uncertain. Inspired by his own idiosyncratic beliefs about Satie as a composer of “duration” rather than conventional harmony, and by Antonin Artaud’s blurring of theater and audience, Cage conceived the broad idea for the performance one morning and by evening had persuaded Charles Olson, the writer and potter Mary Caroline (“M.C.”) Richards, Cunningham, Rauschenberg, and others to participate.

In what must be considered the most reliable—because most immediate—account of what actually happened that night, the writer Francine du Plessix Gray, a student at the time, recorded the event in her diary:

At 8:30 tonight John Cage mounted a stepladder and until 10:30, he talked of the relation of music to Zen Buddhism, while a movie was shown, dogs barked, Merce danced, a prepared piano was played, whistles blew, babies screamed, coffee was served by four boys dressed in white and Edith Piaf records were played double-speed on a turn-of-the-century machine. At 10:30 the recital ended and Cage grinned while Olson talked to him again about Zen Buddhism, [composer] Stefan Wolpe bitched, two boys in white waltzed together, [David] Tudor played the piano, and the professors’ wives licked popsicles.

When Martin Duberman interviewed participants and audience members for his history of Black Mountain fifteen years later, certain aspects of the evening were described a little differently.* Cage remembered girls, not boys, serving the coffee, and added that Rauschenberg’s four all-white paintings were hung above the dining hall; Cunningham couldn’t remember “whether they were the black paintings or the white paintings.” Other memories were more outlandish. The dancer Katherine Litz thought she remembered M.C. Richards arriving on a horse, “or maybe someone was playing the part of a horse.” Asked in 1989 to draw a diagram of Theater Piece No. 1, Richards herself indicated where Rauschenberg played records and Cage stood at the lectern, but she also specified the location of a “Franz Kline suspended painting” rather than Rauschenberg’s white or black paintings.

Faulty memories can account for some discrepancies, but one also suspects a certain amount of self-interested rewriting of history, especially in the way that Theater Piece No. 1 has come to be seen as a precursor of later collaborations. Cage first came to Black Mountain in 1948, as Cunningham’s accompanist, and both artists, who later became life partners, returned to Black Mountain many times. In 1953, Cunningham founded his dance company at the college and the previous year Cage performed his epochal piece 4′33″, in which a pianist sits at an opened piano for exactly four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence. Cage claimed that his so-called silent piece owed a great deal to Rauschenberg’s white paintings. (“To Whom It May Concern,” he wrote rather grandiosely in his book Silences: “The white paintings came first; my silent piece came later.”) Back in New York, Cage, Cunningham, and Rauschenberg continued to collaborate on performances of the Cunningham company. Working separately, each would develop his concept for the piece—choreography, music, sets, and costumes—which were assembled, as in Theater Piece No. 1, for the actual performance.

A section of the ICA exhibition commemorates Theater Piece No. 1 with a grand piano, a screen for showing footage of Cunningham, Litz, and other dancers, a dance floor (for live, happening-like performances), and Rauschenberg’s four white paintings, hung aloft as though presiding over the lost occasion. Nearby, as though hedging bets about what “really” happened, hangs Franz Kline’s superb Painting—with its gestural horizontal swaths of heavily applied black paint overlaying a vigorously textural white ground, like an iron bridge seen from above on a snowy day—painted at Black Mountain in 1952, which may well have been suspended above the barking dogs and screaming babies and bitching professors on that eventful night.

It would be a mistake to think that such seemingly chaotic collaborations were the mainstay of education at Black Mountain, however. The lasting impression of the place on many of the students who went on to successful careers in the arts was, instead, one of intellectual and artistic rigor. Josef Albers, in particular, set a mood of exigent engagement, discouraging, as a student remembered, “the sloppy, the casual, the makeshift.” Three student-artists ubiquitous in the ICA show—Rauschenberg, Ruth Asawa, and Ray Johnson—all took Albers’s design courses, Anni Albers’s exacting courses in weaving, and Cunningham’s equally demanding dance classes.

One would like to hear more than we learn from these exhibitions, or from Duberman’s history, about the Black Mountain curriculum outside of its offerings in the arts. Why, for example, were the classes of the German mathematician Max Dehn, a world-famous figure in geometry who was the first to solve one of David Hilbert’s legendary sets of problems, so inspiring for the painter Dorothea Rockburne? David Silver notes that there were courses in agriculture; one would also like to hear about the courses in the natural sciences and the attempt, during the war, to establish a mica-mining operation at the school. Such activities seem distant from Theater Piece No. 1, though no less a part of a distinctive and still-inspiring experiment in higher education.

It is tempting to see, in the efforts to reconstruct what actually took place during that half-lost evening in 1952, a microcosm of the larger attempt to reconstruct what happened at Black Mountain College generally, during each phase of its precarious twenty-four-year existence. How much of our fascination with the short-lived school is solidly based in historical fact and how much is projection, from the perspective of our own discouraging period of higher education, when so much on offer seems to be a regressive engagement with vocational training of various narrowly conceived kinds accompanied by a deepening distrust of the value of the humanities, let alone the arts?

Today our colleges, so unlike Black Mountain, are built primarily for permanence, with their mausoleum-like buildings of fire-resistant brick and stone, their ceaseless fund-raising and aggressive PR campaigns, and their risk-averse curriculums of a uniform blandness. Could a college willing to take the risks Black Mountain embraced—no endowment, a semipermanent campus, no standard tests, an arts-centered curriculum, a self-sustaining work and farm program, and the rest—make a go of it today?

A friend of mine, Robin Dreyer, the communications director of the Penland School of Crafts, near Asheville, recently sent me a playbill from a production of the Lerner and Loewe musical Brigadoon, staged in a summer theater in the mountain town of Burnsville, not far from Black Mountain, on the nights of August 15, 16, 18, and 19; the year 1952 is scrawled across the bottom. Choreography for the show is attributed to Merce Cunningham, music to John Cage. If Theater Piece No. 1 took place, as it is now surmised, on August 16, 1952, this means that theatergoers in those charmed mountains could choose that night between two very different productions by Cunningham and Cage. Brigadoon, it will be remembered, is a magical village in the highlands that appears for only one day every one hundred years. Perhaps ephemeral colleges are doomed to a similar fate. And maybe the time is about ripe for another appearance of a college like Black Mountain.

-

*

Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community (1972; Northwestern University Press, 2009). ↩