A large part of Thomas Laqueur’s inquiry into modern attitudes toward the dead has to do with “a vast enterprise on a small stage: the work of the dead in western Europe since the eighteenth century.” Among other subjects, he aims to show how the cemetery replaced the churchyard as the main resting place of the dead in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. He also delves into the modern history of cremation. But Laqueur’s central theme is not narrowly historical. It concerns “the long anthropological view—deep time” in which humans have emerged as a species:

The book begins with and is supported by a cosmic claim: the dead make civilization on a grand and an intimate scale, everywhere and always: their historical, philosophical, and anthropological weight is enormous and almost without limit and compare.

Throughout the book, Laqueur’s antagonist is the Greek philosopher Diogenes (circa 412–323 BCE), who is reported to have instructed his students that when he died he wanted his body to be thrown outside the city walls so that it could be eaten by animals. Diogenes did not care what happened to his body after he died, since at that point he would no longer exist. The ancient Cynic originated a long tradition, “running from antiquity to Charles Dickens in the nineteenth century to Jessica Mitford in the twentieth,” according to which much or all of the care we accord the dead is folly. In Laqueur’s view, this tradition is at odds with strong and enduring human needs. Diogenes “was right (his or any body forever stripped of life cannot be injured), but also existentially wrong, wrong in a way that defies all cultural logic.”

The dead body matters “because the living need the dead far more than the dead need the living. It matters because the dead make social worlds. It matters because we cannot bear to live at the borders of our mortality.” The human mind cannot help treating the dead human body as if it were something other and more than a lump of lifeless matter. The Work of the Dead is an extended meditation on this singular fact.

Professor of history at the University of California at Berkeley, Laqueur covers an enormous span of time and space in this book. Moving from Diogenes to Augustine and swiftly on to the eighteenth-century English freethinker William Godwin, he shows how in their different ways the Christian saint and the rationalist thinker responded to Diogenes’ counsel. For Augustine, Christians could be even more indifferent to what happened to dead bodies than the pagan philosopher, since Christians believe humans are essentially immortal souls that do not die but go on to another world. Yet it mattered where the common Christian was laid to rest, and the preferred place for more than a thousand years was near the remains of a saint or some sacred relic. The Christian practice reflects “the very deep human desire to live with our ancestors and with their bodies.” Whether or not they believe in an afterlife, human beings need to preserve their “special dead” from oblivion.

Laqueur shows how the near-atheist Godwin reacted to the death of his beloved wife Mary Wollstonecraft, who died while giving birth to Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein. Like Diogenes, Godwin was convinced that the dead are “utterly dead.” Yet in his Essay on Sepulchres: A Proposal for Erecting Some Memorial of the Illustrious Dead in All Ages on the Spot Where Their Remains Have Been Interred (1809), the devoted rationalist proposed that the places where noteworthy bodies are buried be identified by name and marked on maps like the scenes of famous battles, creating an “Atlas of those who Have Lived, for the Use of Men Hereafter to be Born.”

Here Godwin is a precursor of what Laqueur calls “an age of necronominalism”—the period, “beginning in the late nineteenth century, accelerating after the American Civil War, and ever more so in the century of the Holocaust, the Great War, the Soviet terror and so much more mass death,” in which many have come to feel the need to know the names of the dead and so preserve in memory the persons the dead had been. In Godwin’s case, the impulse to name and place the dead had a directly personal source in the death of his wife. Laqueur writes little that is directly about bereavement; but the death of a loved one is for many people a much greater loss than the prospect of their own extinction. Memorializing the dead bodies of those we have loved is a way of coping with what would otherwise be an intolerable absence.1

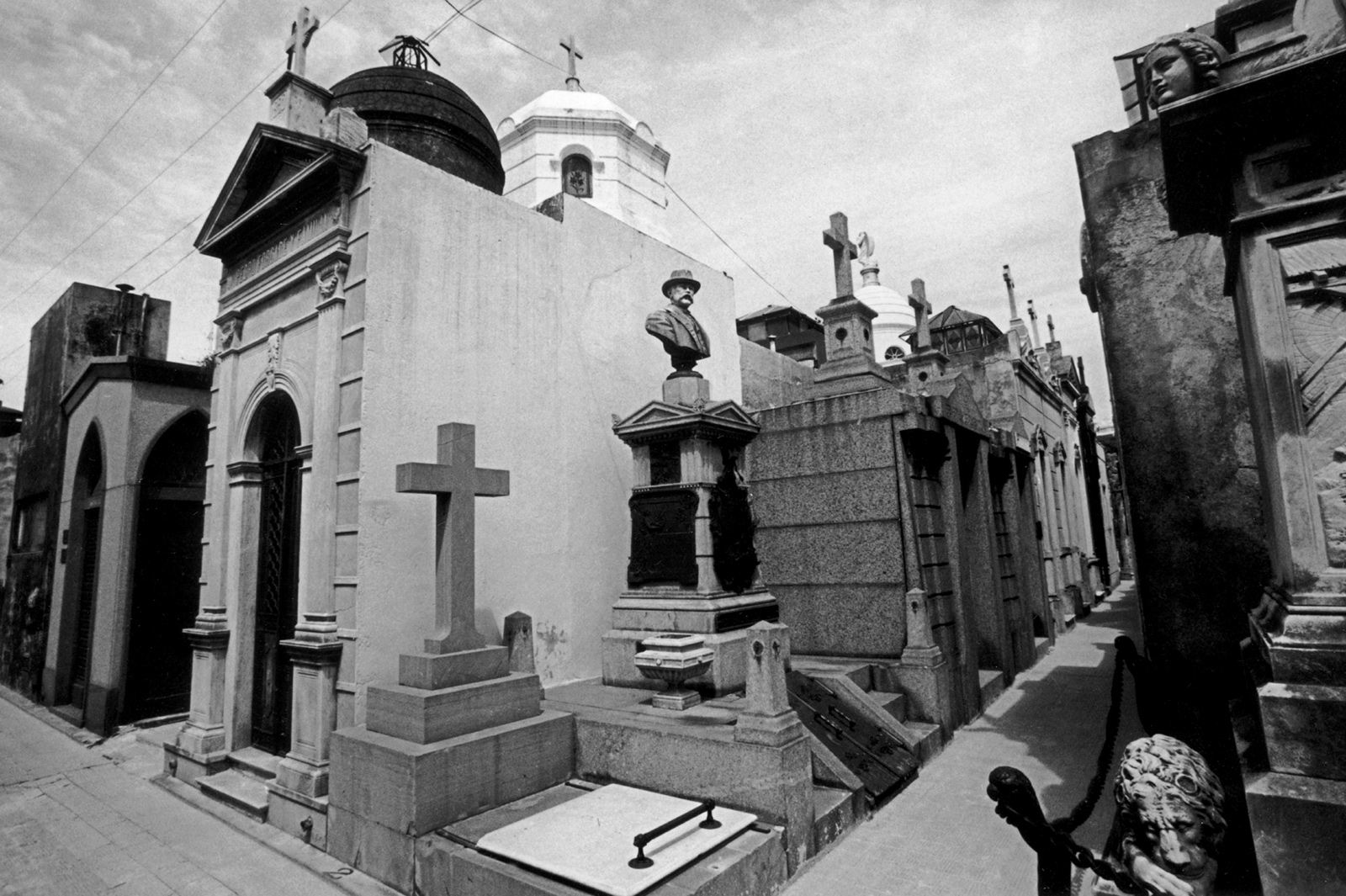

Laqueur’s discussion of how the cemetery supplanted the church graveyard as the chief place of interment is a masterpiece of historical investigation. Showing how a complex mix of factors—including concern with public health, the waning power of the Catholic Church, and the emergence of a belief that the place where one is buried should be a matter of personal choice—produced the shift, he describes how sites were created in which the dead were separated from the living as they had not been when they were interred in or near places of worship. With the rise of cemeteries, the dead could be remembered as individuals and buried with their families in a way that was impractical in overcrowded churchyards.

Advertisement

Hardly a sentence in Laqueur’s long book is wasted and many seemingly digressive passages are actually integral to his argument. Recounting “my own strange story of caring for the dead,” he describes how, when his father died in 1984 and was by his own wish cremated, Laqueur and his wife mixed his ashes into “a flowerbed by the lake cottage in Virginia where his life ended.” When Laqueur was invited to lecture in Germany more than a decade later, his wife suggested that he take some of the ashes with him and mix them with those of Laqueur’s grandfather, whose grave in the Jewish section of the Friedhof Ohlsdorf cemetery in Hamburg he had visited during a previous trip. Both Laqueur and his wife knew there were no ashes left: “They were by now leached away by the snows of winter and rains of summer…nothing of him could possibly be left.” So after some deliberation they finally decided to take “a small bag of dirt in which there might have been a homeopathically small number of inorganic molecules that had once been in my father and to mix these with the soil of his father’s grave”—a gesture, Laqueur adds, that “would have been regarded by my father as an act of rank superstition.”

It is a lovely story, which illustrates the most striking conclusion of Laqueur’s research: the modern “unenchanted”—among whom Laqueur counts himself—know full well that “nothing ‘real’” lies behind the seeming presence of the dead among the living; but they are unable to live with this awareness. It is this inability that has allowed “the reinvention of enchantment” and the emergence of “a new and modern magic.”

Given the book’s vast scope, it is inevitable that there should be some lacunae in Laqueur’s survey of modern attitudes toward the dead. But it is surprising that he tells us practically nothing of the rise in the late nineteenth century of psychical research, though it included notable figures such as Alfred Russel Wallace, codiscoverer with Darwin of natural selection, Henry Sidgwick, generally acknowledged to be one of the most significant moral philosophers of the last two centuries, and Arthur Balfour, British prime minister and a subtle writer on religion.

These late Victorian and Edwardian thinkers were interested in finding rigorously tested evidence that the human mind survives the death of the body—a distinctively modern way of attempting to keep the dead alive among us. Darwin had shown that humans and animals are kin. Why then should not humans suffer the same fate as other animals, with their minds being snuffed out when their bodies die? It was a prospect these thinkers could not endure. Even as they applied what they regarded as scientific methods, they did not give up magical thinking.

A different attempt to use science to bring back the dead occurred in the Soviet Union around the time of Lenin’s death in 1924, about which Laqueur also says next to nothing. He touches on how Marx’s adherents made his grave “a sacred site,” “the tomb of a saint” around which other revolutionary leaders, such as the leaders of the Communist parties of South Africa and Iran, were buried. He makes no mention of the intellectual movement of “God-builders,” which helped shape the decision to embalm Lenin’s cadaver—a group that included the first Soviet minister of trade, Leonid Krasin, who believed that the power of science could be used “to resurrect great historical figures.”2

These Bolshevik visionaries were in no doubt that the human mind is extinguished when the body is finally dead; but they believed that dead bodies could in some cases be reanimated, minds restored, and the persons these bodies had once been returned to life, with the aid of technology. In seeking to reanimate the dead they were at an opposite pole from Marx, who believed (as Laqueur puts it) that “humanity needed an exorcism in order to bring an end to history” and advised revolutionaries to “let the dead bury their dead.” But with the body of Lenin on display in the Soviet state from soon after his death until the state’s collapse and beyond, history did not end. The dead were not exorcised and have remained a troubling presence.

Advertisement

The attempt to deliver humankind (or some portion of it) from death by using technology continues today, but Laqueur does not discuss recent cults that offer to preserve us from oblivion by freezing our bodies in sealed capsules or uploading the contents of our brains into cyberspace. These are also expressions of magical thinking, since while technology may someday be able to achieve such feats, death will not thereby be abolished. Human beings cannot permanently escape death as long as human institutions are mortal. Vulnerable to disruption and destruction by war, economic collapse, and the effects of climate change, the sites that house the frozen cadavers and maintain the virtual minds in cyberspace would continue to be exposed to the contingencies of history. Modern movements that aim to defeat death through the power of science add strength to Laqueur’s claim that modern history “is not…a story of progressive disenchantment,” but one in which humankind continually reenchants itself in new ways.

The largest gap in Laqueur’s account concerns the reasons for humankind’s attachment to its dead. Repeatedly, he tells us that humans are unique in caring in this way. He allows that a small exception might be made for some species of elephants, which “show an interest in the remains of other dead elephants to a greater degree than to other natural objects”; but these elephants “do not select and visit the skulls of their own relatives more than those of unrelated elephants.”

Humans are the only species that cares for its special dead, and have a record of doing so going back “to at least the Upper Paleolithic, 40,000–10,000 BCE, to what used to be called the Late Stone Age.” Humans and other animals “stand on different sides of the border” between nature and culture, and it is the dead that have enabled humans to cross this boundary: “The work of the dead is to make culture.” It does not matter that the dead do not exist. They “remain active agents in this history even if we are convinced they are nothing and nowhere. Their ontological standing is of minor importance. They do things the living could not do on their own.”

It is hard to know quite what is meant by such statements. If the dead do not exist, how can they do anything at all? Laqueur is aware of the difficulty:

I want to make clear that I am not being delusional by claiming that the dead do work, in the sense that a physicist would understand the term…. Diogenes had a point: the dead—or in any case their bodily remains—can do nothing because they are nothing. They cannot even lift a stick to fend off beasts. Consequently, it would seem that they could not do the far more demanding work I have assigned them. With the exception of ghosts and other unquiet spirits—that is, with the exception of the not-quite-dead or the differently dead…—the dead as represented by the dead body are dead. They therefore do not work (or play) in the space and time of our world.

But this only exacerbates the problem. In the disenchanted view of things that Laqueur believes he holds, the fundamental divide between life and death is not between two worlds but between being and nonbeing. There is no “somewhere else” where the dead could act or suffer; when human beings die they leave not only our world but any world. In that case, what can it mean to say that the dead are “active agents”? If this is a metaphor, it seems misplaced and confusing. It is not only that the reader cannot grasp how something that does not exist can do any kind of work. One is left wondering why humans exhibit the concern with the dead that he believes has created civilization. Resolutely, Laqueur refuses to speculate:

As far back as we can go, the archeological record seems to support the view that humans and their close hominid ancestors have cared for at least some of their dead. I do not know what this means in terms of human cognitive development or, more specifically, attitudes toward death. I do not think it matters.

Instead he simply reiterates his claim: the dead “are central to making culture, to creating the skein of meaning through which we live within ourselves and in public.” Perhaps what he means is simply that the dead work within us because we are unable to let our memories of them go; but it is not clear why humans alone should be attached to their dead in this way. The singular fact that is the subject of the book is left unexplained.3

Laqueur would have done better to relax his self-imposed ban on speculation. Is it awareness of our own mortality and of those who are special to us that accounts for our concern with the dead? In that case it would seem that this concern would be found in any creature that is as self-aware as humans. Caring for the dead would be the price of consciousness. But might self-aware robots be designed that are programmed to be indifferent to mortality—their own and that of others? If so, which human attributes would have to be denied them? Would it be the capacity for love? Or a need to tell their lives as a coherent story, which death frustrates? Such questions are unavoidable if Laqueur wants to advance a “cosmic claim” about the place of the dead in our lives. But he sidesteps the hole at the heart of his book. If the dead dwell within us, it is because we want or need them to do so. Caring for the dead is the work of the living.

Marzio Barbagli’s history of suicide is a different sort of book. Cool and forensically analytical in tone, Farewell to the World is instructive in showing the many disparate reasons human beings can have for choosing to quit the scene. A professor of sociology at the University of Bologna, Barbagli’s observes of his fellow practitioners of the discipline:

Sociologists, who have always been fascinated by scientific laws, perhaps because they have never found any themselves, became convinced over time that Durkheim’s theory had at least some of the requisites in order to become such a law, and, not without a touch of irony, they called it “sociology’s ‘one law.’”

The French sociologist Émile Durkheim (1858–1917) regarded suicide “as a symptom of the ills of society”—a view also voiced by Karl Marx, when he observed in 1846 that the annual number of suicides “has simply ‘to be viewed as a symptom of the deficient organization of our society.’” This view, Barbagli writes, is fundamentally mistaken:

The processes of social breakdown were not the only cause, let alone the main factor underlying the rise in suicide numbers up until the early twentieth century. Moreover, it is increasingly clear that an explanation of suicide cannot be fully posited without taking account of the results of studies carried out by historians and anthropologists, psychologists and political scientists. More perhaps than any other action, suicide depends on a vast number of psychosocial, cultural, political and even biological causes and must be analysed from different points of view.

Divided into two parts, one on Europe and the West in general, the other on Asia, particularly India and China, Barbagli’s study can be read as a systematic refutation of Durkheim’s theory. Examining voluntary death “over a very long arc from the Middle Ages to the early twentieth century,” he suggests that the rising suicide rates that prompted concern among thinkers such as Durkheim can be traced to

a number of profound social and cultural changes, beginning in the closing decades of the sixteenth century and the opening decades of the seventeenth, that marked the crisis and decline of that complex of rules, beliefs, interpretative patterns, symbols and rituals linked to Christianity, which for centuries had guarded men and women against the temptation of taking their own lives.

Starting with Augustine, who condemned voluntary death as the gravest of sins in nearly all circumstances, the Christian world prohibited suicide as a crime—according to Thomas Aquinas, “one that was even ‘more dangerous’ than murder since it left no time for expiation.” According to the teaching that developed in the church, Christians “should never succumb to despair.” Even if the situation seems hopeless, they should wait for a miracle. “This system of beliefs,” Barbagli writes, “remained dominant and unchallenged in Europe for over a millennium.” But

the great edifice of values, rules, sanctions, beliefs, symbols and categories of interpretation condemning or discouraging suicide…at some point started to crack and shake, before finally collapsing much later, in spite of all the efforts made to shore it up and keep it standing.

It is a plausible story, but it could have been made more convincing if Barbagli had said more about attitudes toward suicide in pre-Christian Europe. In ancient Greece and Rome, the freedom to end one’s life was socially restricted in numerous ways; but killing oneself was not seen as a crime against God, as has been the case in monotheistic cultures. Among the many reasons that might make ending one’s life reasonable, the Roman Stoic Seneca, in a letter counseling a young friend, included the boredom with life that may come from having sated one’s desires.4 It is impossible to imagine such a view being accepted in a Christian setting, or in many modern secular moralities. As Barbagli notes, the Bolshevik leaders in Soviet Russia condemned suicide as a form of bourgeois individualism: “In the new society, good communists and workers, they maintained, ought not to take their own lives because they belonged not to them, but to the Party and the class.” Rejection of monotheism does not ensure the freedom to end one’s life as one pleases.

Barbagli’s study is rich in examples illustrating the variety of reasons why human beings take their own lives. Some show people escaping repressive policies and societies. Following a campaign launched by Mao against corruption, tax evasion, and fraudulent use of state property in 1951–1952, between 200,000 and 300,000 people are estimated to have committed suicide. Many did so by jumping from the top floors of buildings, since they feared that if they drowned themselves in rivers and their body could not be found, they could be accused of having fled to Hong Kong and their families persecuted. Others show people who had already suffered profound assaults taking their lives. Of around 100,000 women raped by Russian soldiers in Berlin at the close of World War II in 1945, some ten thousand died, “mostly from suicide,” with the fear of being rejected by German society being a major reason the women took their lives.

Still others show people choosing to end their lives in order to escape a lingering death or murder. In Nazi Germany, Jews committed suicide when mass deportation to concentration and death camps began in the autumn of 1941. They did so, according to Tobias Ingenhoven, a lawyer from Hamburg, who had sent his daughter to safety in England, “in order to escape the horrific humiliations and degradations, the hunger and cold, the dirt and the illnesses that await us.” Taking their own life was forbidden to inmates in the camps. For some of those expecting deportation, suicide may have expressed a determination to make at least their deaths their own.

Some use their deaths as weapons, as kamikaze pilots did in World War II. In Chapter Seven, “The Body as Bomb,” Barbagli discusses the phenomenon of suicide bombing, showing how it began to be used in the 1980s by Hezbollah in Lebanon and then by the Tamil Tigers, a Marxist-Leninist group in Sri Lanka. Analyzing suicide bombing as a rational strategy on the part of otherwise weak participants in violent conflicts, he makes an interesting point when he observes that since “suicide attacks are complex operations, requiring considerable skills and expertise, these organizations assign their most delicate and difficult missions to their most educated and expert members.” Though suicide bombers have tended to be poor and uneducated in some countries, including Afghanistan, in many others they have been more prosperous and better educated than most of the population.

The upshot of Barbagli’s analysis is that voluntary death cannot be explained by any single theory. Some useful generalizations can be formulated. For example, “in all Western countries, prison has always been the place where suicide rates are highest”; in almost all Western countries, between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, “the suicide rate among men was almost three times that of women, and in many cases four times,” whereas in China “female suicides were very frequent and…much higher than among men until 2005,” while the suicide rate for Chinese men and women has fallen sharply as growing numbers of the rural population have migrated to the city; according to data collected in 1914, some 3 percent of gay men in Western countries took their own lives; all forms of cancer increase the likelihood of suicide, though to different degrees. But these observations do not add up to any kind of behavioral law. Suicide remains as complex as human life.

-

1

Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking (Knopf, 2005) is a moving and precisely observed account of this aspect of bereavement. See John Leonard’s review in these pages, October 20, 2005. ↩

-

2

For Krasin’s statement on resurrecting “great historical figures,” see John Gray, The Immortalization Commission: Science and the Strange Quest to Cheat Death (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011), p. 161. ↩

-

3

For a bold and intriguing attempt at understanding the part the dead play among the living, to which Laqueur’s book runs parallel in some ways, see Robert Pogue Harrison, The Dominion of the Dead (University of Chicago Press, 2003), who writes: “To be human means above all to bury” (p. xi). See also the review in these pages by W.S. Merwin, April 8, 2004. ↩

-

4

The Epistles of Seneca, with an English translation by Richard M. Grummere (Harvard University Press, 2006), Vol. 5, p. 173: “Reflect how long you have been doing the same thing: food, sleep, lust—this is one’s daily round. The desire to die may be felt, not only by the sensible man or the brave or unhappy man, but even by the man who is merely surfeited.” ↩