Political paralysis. Hyperpartisanship. Decline of political civility. Denial of voting rights to groups that support the opposition. Low voter turnout. There may be other valid grievances about what’s become of our democracy, but that’s a useful list to start with. To mention them raises the question of where to begin to resolve at least some of our political problems. I’m not alone in thinking that the single problem most worth attacking first, the solution to which could go a long way toward untangling our political morass, is the blatantly partisan manipulation of our system of decennial redistricting by the states.

Redistricting works in a circular fashion by which the states get caught up in an ongoing cycle of self-protecting exploitation of the advantages of incumbency. Thus a party wins control of the legislature of a state that then draws its state and congressional districts in a way that maintains that party in power. (Also winning the governorship helps a lot.) With that power the controlling state party can decide to try to limit the voting rights of groups that might disturb this convenient arrangement and elect a president of the other party.

So much of our political commentary is clouded by a perceived and real need to be “evenhanded” (the pressures, especially on broadcasters, and especially from the right, are real) that the picture of what’s going on in our politics is often distorted. The inescapable fact is that Republicans have historically been more attuned than Democrats to the political advantages of gaining and maintaining power at the state level and more inclined to involve themselves in what might seem unglamorous structural questions.

One result is that the Republicans are overrepresented in Congress. They’ve pulled that off by working to dominate state governments and thereby get themselves in a position to draw most of the congressional districts, which gives them the power to perpetuate themselves in Congress. Thus—if they’re of a mind to—they can block whatever a Democratic president wants to do. As a result, we have a distorted contest for power between the two parties for control of the executive and legislative branches.

As of now, through redistricting, the Republicans have built themselves a bulwark against losing control of at least one of the houses of Congress—barring an unusually strong landslide. So well have the House Republicans protected themselves or been protected from a contest from the other party that, according to the Cook Political Report, only 37 out of 435 seats are being contested this year. While the precise number can be affected by other factors such as retirements or whether someone from the opposition party decides to run, redistricting, or incumbent protection, is the overwhelmingly relevant factor.

Since “gerrymandering”—drawing an oddly shaped district to give one party an advantage—has been with us since the early 1800s, what’s so different about the redistricting of today that causes such a fuss, if not yet a sufficiently strong one? The early gerrymandering was quaint compared to the current practice. The system for protecting incumbents that was used for over two centuries has turned into something else.

The Republican sweep of the House in 2010 led to efforts—and an opportunity—to preserve those gains, or as many of them as possible, by transforming the practice of redistricting in the individual states into a national party effort to shape and maintain a House majority. That effort employed sophisticated means—organized computer data that show the block-by-block makeup of an area—and money from the party and allied interest groups to win and keep power in one of the houses of Congress, irrespective of what happens in the presidential election or the overall party breakdown of the votes for the House.

The sorry story of how the House of Representatives became unrepresentative is clearly laid out in a new book, Ratf**cked: The True Story Behind the Secret Plan to Steal America’s Democracy. Despite the wise-guy title, David Daley, editor in chief of Salon and digital media fellow at the Grady School of Journalism at the University of Georgia, has written a sobering and convincing account of how the Republicans figured out the way to gain power in the state legislatures and, as a consequence, in the federal government through an unprecedented national effort of partisan redistricting.

By contrast the Democrats simply weren’t as interested in such dry and detailed stuff as state legislatures and redistricting. Besides, as a Democratic strategist told Daley, “The Republicans have always been better than Democrats at playing the long game.” Daley argues that the Democrats blew it after their triumphant election in 2008 of the nation’s first black president. The celebration went on too long. For the Republicans, Obama’s victory represented the threat of long-term Democratic dominance.

Advertisement

The thing to do, some Republican operatives concluded, was to focus on winning as many seats in state legislatures as possible in the 2010 midterm election and then press that advantage in the redistricting that would follow—picking up federal and state seats to offset Obama’s 2008 victory. The result was the Republican 2010 sweep of state governments as well as the House of Representatives—they picked up a stunning sixty-three House seats (taking control of the House) and six Senate seats (expanding their minority status), and also took control of twenty-nine of the fifty governorships and twenty-six state legislatures (to the Democrats’ fifteen).

At the time, national attention was on the congressional sweep, which resulted mainly from a major Republican assault on Obama and the recently passed Affordable Care Act and an effort (essentially guided from Washington) to form the Tea Party, an antigovernment “grassroots” movement. But arguably the more significant result of the 2010 election was that in the states the Republicans were in a position to redraw most of the congressional districts—and they did so with an unprecedentedly high-powered national project called REDMAP, or Redistricting Majority Project.

REDMAP was a new way to aim for successful partisan redistricting by concentrating first on winning the greatest majority possible in the congressional and state elections preceding the next Census and using the state majorities to redraw the districts. So successful was the Republican-dominated redistricting after 2010 that, in 2012, while the Democrats won 1.5 million more votes for Congress than the Republicans did, they gained only eight seats, hardly a change at all. Thus the Republicans, sheltered by the previous redistricting, held a thirty-three-vote advantage in the House despite the fact that they’d been decisively outvoted.

And then, in the next midterm election, in 2014, the Republicans parlayed dislike of Obama and their advantage from the redrawn districts into another wave of successes in gaining more congressional and state-level seats. The resulting situation was overwhelming Republican political power at the state level after 2014: they controlled thirty-two governorships, ten more than they had in 2009; they also controlled thirty-three of forty-nine state houses of representatives, and thirty-five of forty-nine state senates. (Nebraska has a unicameral state legislature.) Democrats held 816 fewer state legislative seats than they did before Obama was sworn in as president.

The Democrats to some extent brought this on themselves by not bestirring themselves to vote in the midterm elections. Only 36.6 percent of registered voters bothered to cast a ballot in 2014. The Democrats didn’t begin to organize themselves to offset the Republican advantage in drawing congressional lines until 2014, when they formed a super PAC, Advantage 2020, to do so; but they didn’t hold their first national meeting until December 2014. As far as control of the House is concerned, barring an overwhelming landslide this year the Democrats lost the decade.1

Daley’s important contributions are to give us the history and to describe the impact of the Republican advantage in drawing districts after 2010. In doing so he joins a running argument over what, exactly, contributed to the notable increase over the past few years in political polarity and gridlock in Washington. On this question, many people have been influenced by the book The Big Sort, by Bill Bishop (2008). The nub of Bishop’s argument is that people are increasingly choosing to live among the like-minded and this has contributed to increased partisanship and paralysis.

Daley essentially dismisses this thesis and makes what seem more convincing arguments about what has caused these developments:

The problem with our politics is not that all of us are more partisan, or the Big Sort. It’s that we have been sorted—ratfucked—into districts where the middle does not matter, where the contest only comes down to the most ideological and rancorous on either side. Because the Republicans drew the majority of these lines, there are more rancorous Republicans than Democrats.2

(The House Democrats who recently staged a sit-in on the House floor to push for consideration of a gun bill might have done well to keep this point in mind; if the day comes when they’re in the majority, the Republicans can be counted on to outdo them in disrupting House proceedings.)

Daley also explains one of the most important developments in recent years: the near disappearance of moderate Republicans. Democratic presidents from Lyndon Johnson to Bill Clinton could rely on moderate Republicans to help them pass their initiatives, while Obama has had virtually none. Where did the Republican moderates go? The answer is that most of the House moderates were eliminated by Republican redistricting. In drawing safe districts, the Republican mapmakers diminished the forces within a district—Democrats, minorities—that might pull a Republican representative to the left.

Advertisement

Senators aren’t redistricted, of course, but moderate Senate Republicans were subjected to the same political trend faced by moderate House Republicans: their renomination could be challenged from their right. Even reliable conservatives weren’t safe. The defeats for renomination of senior Republican Bob Bennett of Utah in a state convention in 2010 and Eric Cantor of Virginia in a primary in 2014 by Tea Party–backed challengers scared their colleagues.

In recent years, elections have been increasingly settled in the primaries. The near liquidation of moderate Republicans has virtually ended bipartisan coalitions that might support a Democratic president’s initiatives. And coalitions of Republicans and moderate Democrats in support of Republican proposals were also greatly diminished as a result of Republican line-drawing that lopped off areas, mainly in southern and border states, that had produced most of those moderate Democrats, or Blue Dogs. This led not only to fewer Democratic House seats but also to the gradual reduction of moderate Democrats, to the point of near extinction.

Former Democratic congressman John Tanner of Tennessee, a cofounder of the Blue Dog caucus, who was inclined to try to work with Republicans, ended his House career after eleven terms because he knew that Tennessee Republicans would eliminate his seat in the redistricting after the 2010 census.

Another Blue Dog who threw in the towel because of likely redistricting was Heath Shuler of North Carolina, once a star NFL quarterback and a prize Democratic recruit in 2006. After serving three terms, Shuler saw what the North Carolina Republicans had done to his district—splitting Democratic Asheville in two and turning his former district into one of the most conservative in the state—and decided not to run again. (Daley points out that Shuler’s story also defies the Big Sort theory: that like-minded people might have gravitated to Asheville but if so, Republican line drawers could and did cut down their political power.) As a result of such a nationwide effort at redistricting, Tanner told Daley:

I’d say 300-plus [House] seats are responsive to the most partisan elements of our society…. The middle? Where most of the people are? There is no middle here. And when you lose the middle, you lose the ability to govern a diverse society like the United States of America. We can’t even do the small problems now, much less the big ones.

Thus the House has refused to take up an immigration bill (a lot of people thought, erroneously, that it was support for immigration reform that sunk Cantor), and Congress couldn’t produce before the July 4 recess an appropriation of emergency funds requested by the president in February to combat the spread of the Zika virus.

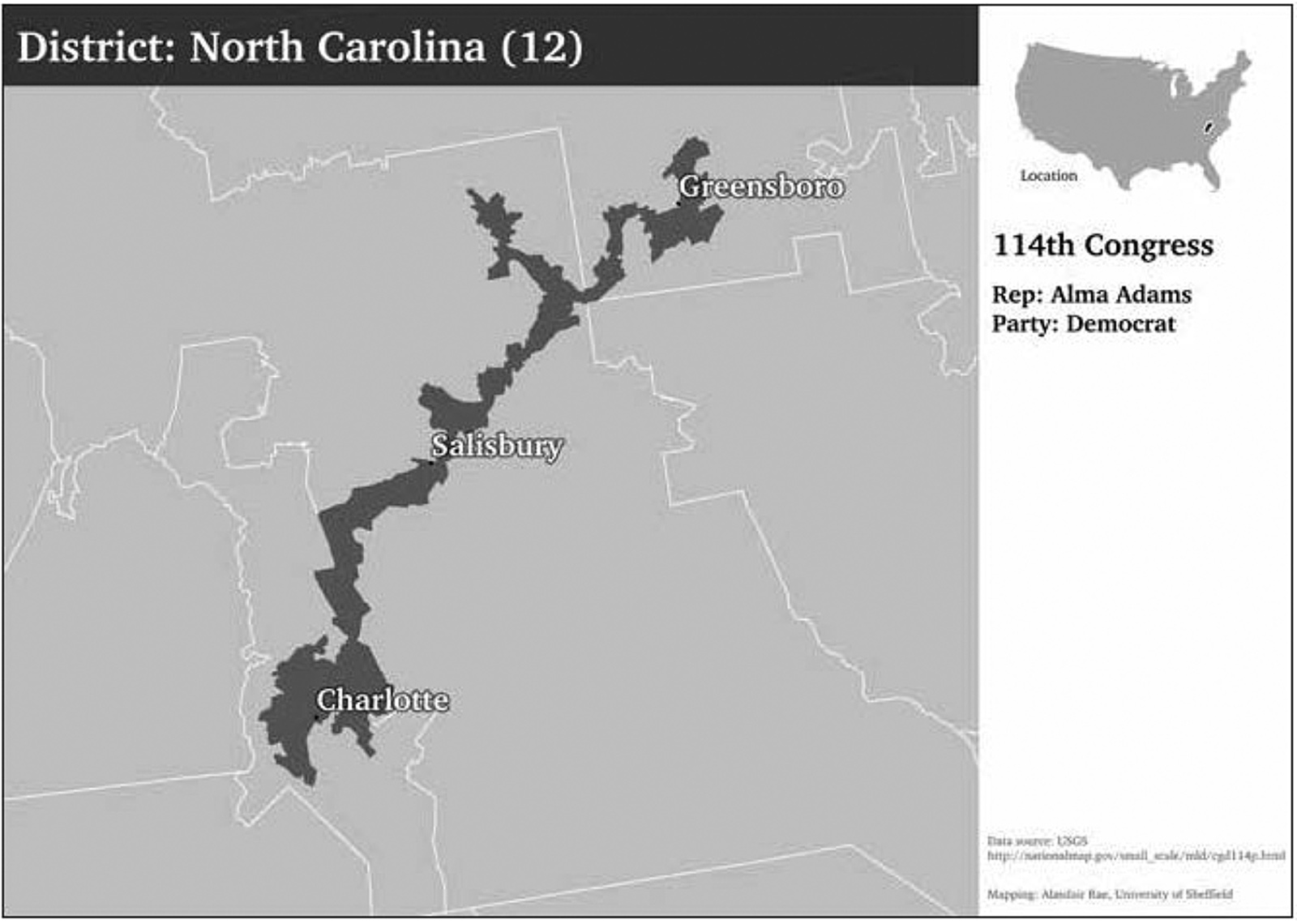

Thus redistricting virtually wiped out white southern Democrats in the House who remained after the civil rights bills of the mid-1960s led many of them to change parties or go down to defeat and who survived the 2010 Republican sweep. Moreover, redistricting after 2010 by Republican legislatures in the South increased the number of blacks (who voted Democratic) in “majority-minority” districts—i.e., made up overwhelmingly of blacks—and in doing so cut the number of minority votes in the few remaining southern districts still held by white Democrats, who were by now approaching extinction in the South.

This apartheid approach left southern blacks in power in limited districts but it also prevented them from influencing white members if they were in the same district. The arrangement suited black leaders who wanted to be sure that some of their own would be in Congress. The same phenomenon of majority-minority districts also occurs in some northern districts. Thus Daley makes a persuasive case—based on behavioral evidence and not theory—that redistricting has played a decisive part in increasing polarization in Washington.

Tanner explains to Daley a phenomenon well understood in Washington but one that deserves widespread understanding: “I saw the gridlock…. These guys are trapped in this system wherein the only threat is from their base in a primary.” If a Republican strays from the far ideological right, Tanner said,

they put themselves in political peril. They know better—some of them—but it’s not worth the political fallout to wander into the sensible center and try to sit down and work something out. No one will do what they all know has to be done to keep the country from going adrift. Is that because of redistricting? Hell, yes.

Daley tells the interesting tale of how a young southern Republican strategist named Chris Jankowski recognized that the Republican sweep in 2010 showed that nearly permanent Republican districts could be nailed down by working to affect the state redistricting that was to come. At that point, while about six states did their redistricting through nonpartisan commissions or commissions working with the legislatures, the rest mostly left the process to the legislatures. Through REDMAP, Jankowski looked for states where changing the political majority in just a few districts might change the makeup of the House.

Most favored for action were states where the governor was also a Republican so that there wouldn’t be a veto of a legislative plan. Jankowski worked with other Republican groups such as the Republican Governors Association, the US Chamber of Commerce, and ALEC (the American Legislative Exchange Council, funded by conservative organizations and businesses). Some corporations such as Walmart and tobacco companies also chipped in money for the effort. Karl Rove’s American Crossroads, a conduit of funds for the Tea Party, was another ally. The project was also partly funded by undisclosed contributions—dark money.

Jankowski told Daley that the group was shaping state governments in a way that would guarantee Republican dominance for at least a decade. One critically important consequence of taking over state legislatures was that it furthered the Republican goal, backed by Rove, of denying voting rights to groups inclined to vote for Democrats—the great evil of our contemporary politics. According to various reports, efforts through state laws to deny votes to blacks, students, and the elderly—for example by requiring photo IDs—are succeeding to a greater extent than ever. This, in turn, helps the Republicans keep the majority of state legislatures in their own hands, elect more Republicans to Congress, and help the Republican presidential candidate carry more states.

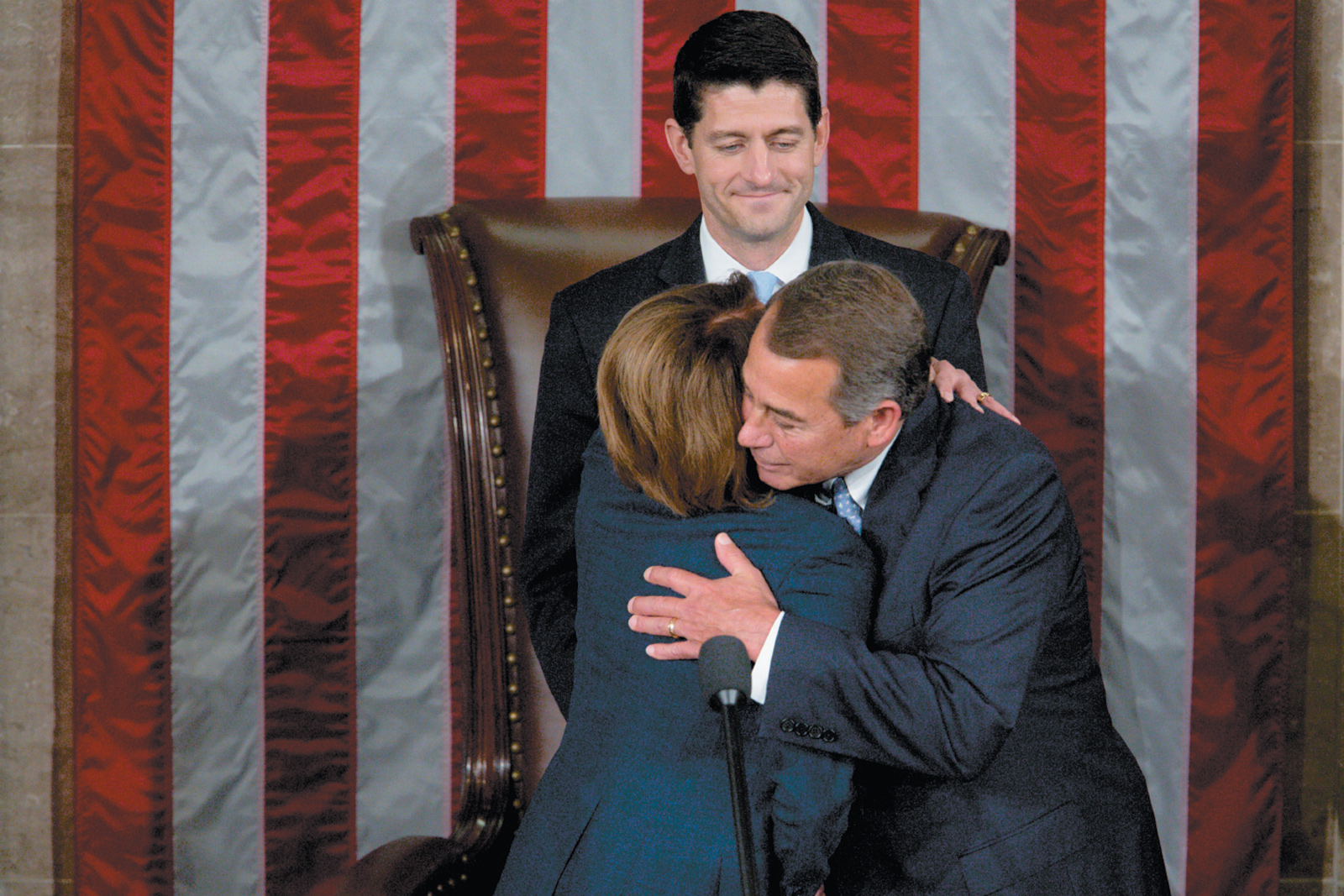

Daley closely examines Republican efforts to control redistricting in various states. In the case of Ohio, “the most contested prize in presidential politics,” Daley writes, the project began in 2011 and was carried out through “maps drawn by some of Ohio’s smartest political strategists” and in cooperation with then House Speaker John Boehner, who represented a district just outside Cincinnati. Until 2010, Ohio’s congressional districts were roughly evenly divided between the two parties. Boehner’s encouragement of partisan redistricting to win and then increase his House majority ended in his own defeat. The process encouraged members to turn right rather than be defeated in the primaries. Thus the forces unleashed by the partisan redistricting led to Boehner being challenged by members of the Freedom Caucus, who were, if anything, to the right of the Tea Party, and they brought him down in 2015.

Daley cites revealing e-mails obtained by the Ohio Campaign for Accountable Redistricting. One set of e-mails showed how a tiny peninsula was added at the last minute to a new district in northeast Ohio not because it contained certain residents but because it was the site of a large manufacturing company that could produce campaign contributions. In another last-minute change, the mapmakers snuck into a part of the Democratic district containing Columbus an area in which major insurance companies were located. They did this to support incumbent Republican Steve Stivers, a former banking lobbyist.

Obama’s victory in 2008 had helped Democrats take the Ohio state House, so the REDMAP project allocated nearly $1 million to turn around enough state House districts in 2010 to hand the chamber back to the Republicans. Though a national Republican or Democratic victory often carries a state legislature along, something different happened after the 2012 election. Because the redistricting had provided “sandbags” against the Democratic wave that carried both Obama and liberal Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown to reelection victories in 2012, the Republicans held their advantage in state and federal seats. Though Ohioans cast only 52 percent of their votes for Republican congressmen, the resulting delegation to the House of Representatives consisted of twelve Republicans and four Democrats, or 75 percent Republican.

The question must be asked: Is that representative government?

The partisan distribution of House seats leads to the situation in which, while majorities of Americans support gun control measures, are pro-choice, and worry about climate change, their views don’t have proportional representation in Congress. (Don’t be misled by the latest proposal barring terrorists on the no-fly list from buying guns: not a single mass shooting so far has been carried out by a terrorist on the list and it’s not clear that the Orlando shooter’s gun purchases would have been stopped under this proposal; but connecting gun control to stopping terrorism might just defy the NRA.)

Sam Wang, a Princeton neuroscientist who doubles as a political scientist and is known for his highly accurate computer models of voter behavior, was struck by the effect of the post-2010 reapportionment on the results of the 2012 election, which denied any real relation between voters and House members. He observed that 2012 was only the second time since World War II that the party that won the most overall votes for Congress didn’t capture the House. The other was in 1996 when Republicans and their allied interest groups, knowing that Bob Dole would lose to Bill Clinton, concentrated their efforts on maintaining the Republican House majority won in Newt Gingrich’s 1994 “revolution,” and thus though the Democrats won the majority of the races, they were prevented from taking back the House. Wang’s analysis concluded that the post-2010 gerrymander was “historic and different from others in the modern era.”

Wang’s computer exercises showed that if in 2010 all the districts had been drawn in a nonpartisan manner, “control would have been within reach for the Democrats.” And if the Republicans only narrowly controlled Congress, they would have been forced to compromise with the Democrats. That is, unless they wanted to pass nothing at all.

What is to be done about partisan districting? Fortunately, a workable answer isn’t obscure or unachievable. The process has to be taken from the parties and turned over to nonpartisan commissions. But for the most part, the Democrats aren’t seeking to change the system that the Republicans have done such an effective job of exploiting; their aim is to emulate the Republicans. Only six states—Arizona, Iowa, California, Washington, Idaho, and New Jersey—use some form of nonpartisan commissions, some with provisions for involvement by the legislature though the legislature itself doesn’t draw the lines. Efforts to move to a less partisan redistricting are being made in a few more states: Florida, Maine, and even Ohio (though its process would involve only state districts and would still involve the parties).

Paradoxically, then, the most important procedural impediment to the working of democracy is also the easiest to fix. It’s more conducive to a solution than, say, campaign finance reform or even voting rights (both of which, particularly the latter, would be easier to fix after fair redistricting). What is required is a sufficient number of people who understand the issues at stake to bring pressure in their state to rectify its districting system. Of course, as with all the issues of distorted political arrangements, those who benefit from the existing system are its strongest defenders. But embarrassment can be a potent political force and blatant denial of even the concept of representative government should be quite embarrassing.

Since commissions are obviously the most promising way to go toward taking the partisanship out of redistricting, why hasn’t more been done in this direction? Redistricting is so political that institutions that might deal with it have steered clear of the subject. Congress uses the excuse that this is a matter for the individual states to resolve though it could assert jurisdiction over the rules for federal elections. But members of Congress were elected under the existing system, and this is a powerful incentive for maintaining the status quo. A congressional aide said to me, “That’s simply a nonstarter.” (The same “reasoning” applies to campaign finance reform.)

Well, then, what about the courts? On occasion a lower court will reject a state’s redistricting plan as blatantly unfair. The Supreme Court has been chary of setting overall standards on this highly political subject, essentially seeing it as the province of the states. Some activists are developing cases challenging instances of blatantly partisan redistricting that they hope will reach the Court someday. Yet that could be a long shot depending on whether such a case will get to the highest court and also the makeup of that court when the case gets there. Citizen action of the kind that would push for redistricting commissions can be quite effective once the public is armed with the facts and determined to push for change. The information is at hand; what’s needed now is the will in numerous states to force the powers that be to make this most fundamental and consequential reform of our political system.

-

1

David Wasserman, an expert in House elections, says Democrats might need to win 8 percent more votes in 2016 to reach a base House majority of 218 votes. Wasserman adds that some districts don’t have Democratic candidates for 2016 because the Democrats didn’t foresee the nomination of Donald Trump, which could hurt Republicans lower on the ballot. ↩

-

2

A respected political scientist, John Sides, argues that the Big Sort may never have happened. See “Maybe ‘The Big Sort’ Never Happened,” The Monkey Cage, March 20, 2012. ↩