1.

“I heartily wish some person would try an experiment upon him,” wrote an army physician at Fort Ticonderoga about the enigma that was Brigadier General Benedict Arnold, “to make the sun shine through his head with an ounce ball; and then see whether the rays come in a direct or oblique direction.” Military colleagues described Arnold as bullheaded, tactless, volatile, and imperious, always ready to ridicule those with whom he disagreed. When an officer doubted his authority to command a naval fleet on Lake Champlain, Arnold, as one witness observed, proceeded to “kick him very heartily.”

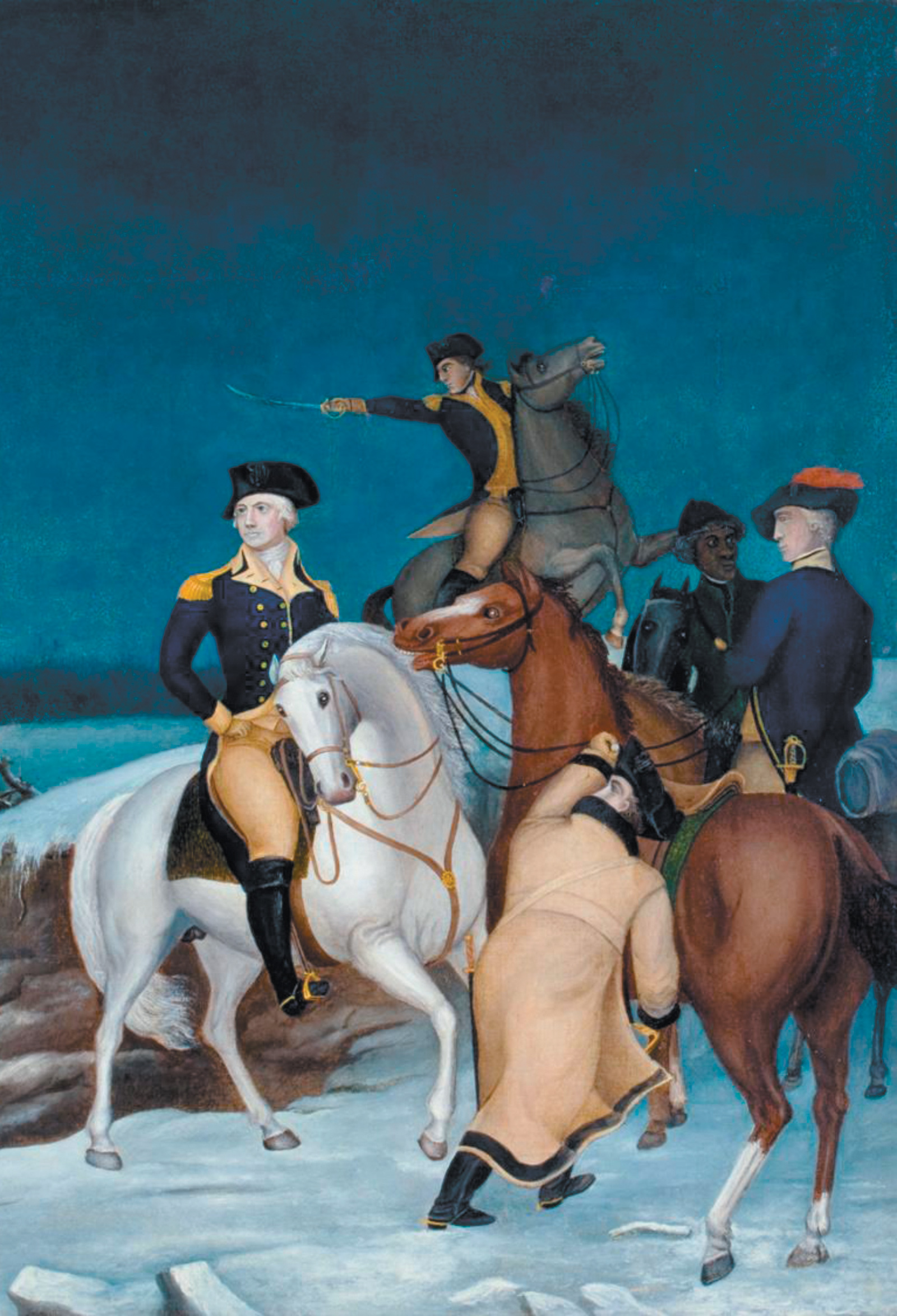

Yet others praised Benedict Arnold for instilling both discipline and confidence in his troops and for “remarkable coolness and bravery” under fire. Even the British secretary of state for the colonies saw him as “the most enterprising man among the rebels.” With a keen understanding of military strategy and an ability to almost instantly assess the strengths and weaknesses of the enemy, Arnold piled up victories at Fort Ticonderoga, on Lake Champlain, at Fort Stanwix, and in the battles of Saratoga. He was one of George Washington’s most spirited and valued officers.

Given the fragility of the revolutionary army, though, Washington was troubled by Arnold’s headstrong actions on the battlefield. They were a source both of Arnold’s charismatic leadership and of risk to the American cause. “Unless your strength and circumstances be such, that you can reasonably promise yourself a moral certainty of succeeding,” Washington had cautioned him in March 1777, “confine yourself in the main to a defensive opposition.” Seven months later, spearheading the Second Battle of Saratoga at Bemis Heights near the Hudson River against German soldiers fighting for the British, Arnold “sat conspicuously on his horse waving his sword with such abandon that he slashed the head of an American officer without realizing it.” Minutes later, he led a brilliant, unorthodox charge with a score of riflemen that turned the tide of the battle. But no sooner did he demand the enemy’s surrender than a German soldier raised his musket and fired. The shot crashed into Arnold’s left thigh and killed his horse. “I wish it had passed [through] my heart,” Arnold said afterward, perhaps realizing that the injury would cripple him for the rest of his life.

Nathaniel Philbrick’s Valiant Ambition is a suspenseful, vivid, richly detailed, and deeply researched book about the revolutionary struggle that bound George Washington and Benedict Arnold together and about the almost disastrous dysfunction of America’s revolutionary government that helped drive them apart, serving as a pretext for Arnold’s dastardly betrayal—his conspiracy to surrender the American fortress at West Point to the British.

Philbrick, the author of Bunker Hill, Mayflower, and In the Heart of the Sea, which won the National Book Award, underscores the manifest incompetence of the wartime Congress under the Articles of Confederation it adopted. Hobbled by factionalism, a clamor of armchair generals, and the absence of strong executive power, the legislature failed to provide resolute support to the Continental Army or even to properly clothe and feed the soldiers who rallied to the revolutionary cause. In February 1778, Commander in Chief Washington drafted an extraordinarily detailed and far-seeing blueprint for the total reorganization of the army, but change was agonizingly slow in coming. While members of Congress contemplated the fortunes of war in easy chairs by a good fire, Washington’s own soldiers, he fumed, slept “under frost and snow.” And yet, he added, the men bravely submitted to such hardships with “patience and obedience which in my opinion can scarce be paralleled.”

Washington was beset by a Congress that monopolized and politicized every decision. It refused to allow him to choose the officers on whom he depended or to grant them the recognition and advancement they deserved. When Benedict Arnold was denied promotion to major general in early 1777, Washington pronounced himself embarrassed on his officer’s behalf, promising to help “remedy any error that may have been made.” He urged Arnold not to “take any hasty steps”—he was, after all, scarcely alone in being slighted by the legislators—but a mortified and smoldering Arnold could not fathom why he was treated as if he were an officer “of no consequence.” Moreover, Congress had proved reluctant to reimburse the money he had put up at the beginning of the war to raise troops.

Finally, almost a year later, in January 1778, Washington brought the good news that Arnold had received the commission of major general and later presented him with a new pair of epaulets and a sword knot “as a testimony of my sincere regard and approbation of your conduct.” But there would be no battlefield command; with Arnold still not recovered from the leg wound suffered at Bemis Heights, that spring Washington named him military governor of Philadelphia.

Advertisement

By then, an embittered Arnold, after sacrificing health and fortune to his country without receiving the distinction he felt was his due, would seek to recover at least the money owed to him. And his position as the most powerful military figure in Philadelphia presented him with ample opportunity in the graft and smuggling trades.

Money, however, could not sate Arnold’s burning ambition and hunger for recognition. Perhaps his commander, General Washington, could identify with that drive, for during the French and Indian War, Washington, then a twenty-three-year-old major in the Virginia militia, had made an arduous journey to Boston to appeal for a commission in the Royal British Army, only to have his request denied. Yet now, leading the fight for independence, Washington realized that far more was at stake than self-aggrandizement; Americans, he exclaimed in 1779, were fighting for the “cause of mankind.”

But Benedict Arnold had begun to suspect that the “cause of mankind” might lie with service to the other side, the British. Arnold’s personal discontent, as well as his anxiety over mounting charges of corruption in Philadelphia, merged with the ongoing military stalemate to lead him to the conclusion that the American experiment in independence had failed, that it was time to appease the British and return to the orderly, peaceful society the American colonists had formerly enjoyed.

He sent out his first feelers to the British early in May 1779. In a tense account of the renegade officer’s sulfurous scheme, Philbrick tracks Arnold’s road to treason, mapped out with his Loyalist wife. In his pursuit of glory and remuneration, he established contact with Captain John André, the head of British intelligence operations, and British Commander in Chief Sir Henry Clinton. When Arnold was installed as commander of West Point in August 1780, suddenly it was all within his reach—the surrender of America’s most important fortress to the British, the collapse of the Revolution, and, as Philbrick writes, “the happy reunification of the British Empire,” with Benedict Arnold “hailed as the deliverer of his once divided country.”

But at the last minute, André’s carelessness—he mistook an American militiaman for a German soldier and identified himself as a British officer—led to his capture and to the quick unraveling of the entire plot. Arnold bolted to the British army, while André soon faced Washington’s hangman. “Whom can we trust now?” the sad and shocked commander in chief sighed to his aide Lafayette. Even as his name became a byword for treason, Benedict Arnold was unapologetic, always maintaining that he had acted out of love for his country and that the war between Great Britain and its colonies had been a misguided and tragic error.

While Arnold attempted to mask his opportunism and disloyalty in a cloak of patriotism, he may have served a useful purpose. Philbrick makes the interesting argument that Arnold’s stunning betrayal “alerted the American people to how close they had all come to betraying the Revolution by putting their own interests ahead of their newborn country’s.” And it laid bare the dangerous combination of a loose, ill-governed confederation of states and the absence of citizens’ loyalty to a still-undefined nation, convincing some American leaders that, after winning independence from Great Britain, they would have to find a way to balance the principles of freedom of 1776 with the need for a strong, unifying government. The Revolutionary War represented the “cutting” phase of the American experiment, in Lord Acton’s famous words. When the war was over, the more consequential and lasting “sewing” would have to begin.1

2.

Historian Joseph Ellis masterfully illuminates the “untrodden” path, as Washington put it, that led to that crucial stage of sewing together the elements of a new country. Unlike the subversive conspiracy hatched by Benedict Arnold to destroy the alliance of independent states, now there would be a conspiracy of sorts to create the political frame for a nation. The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, 1783–1789 uncovers the dramatic story of how four of the most committed American nationalists—George Washington, John Jay, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison—together engineered the coup that brought our republic into being. (Disclosure: I read an early draft of Ellis’s manuscript when it was tentatively entitled “Founding Coup.”) When Abraham Lincoln memorably said in 1863 that “four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation,” he was off by eleven years. Ellis persuasively argues that there was no nation in 1776, but rather a provisional union of thirteen colonies, soon to be states, that came together to win their independence, then go their separate ways.

Advertisement

Ellis, winner of the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize, author of His Excellency: George Washington, American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson, and Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation, points to a kind of dead zone in American history between the British surrender at Yorktown in 1781 and the Constitutional Convention in 1787. We tend to picture a smooth, unimpeded, ineluctable path from revolutionary war to constitutional republic and nationhood. But a great many of the American colonists who had demanded independence from Great Britain in 1776 had no wish to become a nation. Their Declaration of Independence stated that “these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States.” And those states had no intention of relinquishing their sovereignty.

After the war, the states, if anything, steadily moved further apart. They behaved much like small nation-states, with more conflict than cooperation characterizing relationships among neighbors. Most Americans, living out their lives within a thirty-mile radius of their homes, did not object to those centrifugal forces. They thought of their “country” as Massachusetts, Virginia, New York, or South Carolina. The idea of a strong, consolidated nation was viewed as an American version of British tyranny from which they had only recently escaped.

The eventual calling of a constitutional convention, the brainchild of the four members of the quartet, represented, as Ellis demonstrates in his deeply insightful book, an entirely unexpected and dramatic change in direction. Alexander Hamilton was the first among the four to chart that new course, eager to turn debilitating disunity into the strengths of a powerful union. Already in 1780, the twenty-five-year-old aide-de-camp for General Washington blasted the Confederation as fit neither “for war, nor peace,” and proposed instead a “solid coercive union.” In the summer of 1783, as a delegate in the Confederation Congress, he drafted a resolution calling for a convention to amend the Articles of Confederation by establishing stronger executive and judicial branches and by empowering the legislature to impose taxes.

The young man’s proposal, Ellis writes, constituted “a generic blueprint” for what would become the Constitution. At the core was Hamilton’s demand for a federal government with a mandate to govern, a plea that John Jay, the Confederation’s secretary of foreign affairs, endorsed. “I have long thought and become daily more convinced,” Jay wrote in 1786, “that the Construction of our federal Government is fundamentally wrong.” Greatly troubled that “our affairs seem to lead to some Crisis, some Revolution,” he admitted feeling “uneasy and apprehensive, more so than during the war.”

For his part, George Washington, scarred by his wartime experiences with Congress, avowed that “No Man in the United States is, or can be, more deeply impressed with the necessity of reform in our present Confederation than myself.” For Washington, the issue was stark. “We are either a United people or we are not,” he wrote in 1785. “If the former, let us, in all matters of general concern act as a nation…. If we are not, let us no longer act a farce by pretending to it.”

James Madison came later than Washington to that conclusion. For him as for others, an insurrection that began in the late summer of 1786 by two thousand farmers in western Massachusetts was the last straw. Shays’ Rebellion sparked a vigorous exchange of anxious letters among the quartet. In Madison’s mind, the Confederation was on the verge of collapse. “The crisis is arrived,” he told Washington. Americans had to decide “whether they will reap the fruits of that Independence…or whether…they will renounce the auspicious blessings prepared for them by the Revolution.”

By then, a small opening for reform had appeared. Early in 1786, Congress approved a conference at Annapolis to discuss matters of interstate commerce. Madison and Hamilton attended the meeting, representing Virginia and New York, but delegates from only three other states showed up. Lacking a quorum, all they could do was meet and adjourn. But before the delegates dispersed, Alexander Hamilton rose to the occasion with what Ellis characterizes as “a display of almost preposterous audacity.” Just as the conference drew to a close, Hamilton announced that the delegates had unanimously agreed to call for “a future Convention” that would forgo incremental adjustments and instead tackle at once all the problems plaguing the confederation. That convention, he peremptorily added, would take place in Philadelphia on the second Sunday in May 1787. “No one with any semblance of sanity,” Ellis remarks, “could possibly believe that Hamilton’s proposal enjoyed even the slightest chance of success.”

And yet it happened. The Confederation Congress endorsed Hamilton’s suggestion, though members assumed that, as Ellis puts it, “some kind of modest reform defined the parameters of the possible.” The quartet was determined to go further, but first their leader, George Washington, had to be persuaded to retract his promise “never more to meddle in public matters” and attend the convention. Jay, Hamilton, and Madison played the patriot card, pleading that Washington’s absence would sink the very agenda he himself had privately advocated. Their assaults on his conscience worked; Washington agreed to join the Virginia delegation and received a condensed tutorial in political theory from his three collaborators.

But the reluctant decision of the “most nationalistic of the nationalists” to attend the convention was also prompted by Madison’s assurance that the convention would go for broke; halfway measures, they both understood, were not worth the effort and not worth Washington’s presence. Chosen as president of the convention, the general bestowed credibility on a bold venture that might otherwise have been dismissed as illegitimate. The calling of a convention with the radical potential to replace, and not just revise, the Articles of Confederation was, Ellis writes, the quartet’s “first coup.”

On May 25, 1787, the most consequential political meeting in American history began in the East Room of the Pennsylvania State House, where delegates confronted the quartet’s “second coup.” Even before all the delegates had arrived, Madison’s nationalist allies preemptively ensured that his far-reaching outline for government, called the Virginia Plan, would serve as the meeting’s agenda.

Ellis deftly recounts the momentous arguments, maneuvers, compromises, and decisions made in that East Room and puts emphasis on the two “ghosts at the banquet.” One was monarchy, which haunted all conversations about executive power. The other was slavery, which could not be addressed directly for fear of blowing up the entire convention along sectional lines. The net result was a muted and generic definition of the executive branch and an implicit acceptance of slavery, which northern abolitionists would later describe as “a covenant with death,” though any explicit condemnation of slavery would have meant that there was no American republic for Lincoln to subsequently save.

By mid-September, a new Constitution had been drafted and signed, and the delegates returned home. Clandestinely and purposefully, Washington, Hamilton, Jay, and Madison had steered a loose alliance of states toward the establishment of a new governmental conception in which the question of sovereignty was left ambiguous, a political compromise that Madison initially regarded as a major defeat. This conception would be based on two principles: “that any legitimate government must rest on a popular foundation and that popular majorities cannot be trusted to act responsibly”—“a paradox,” Ellis judges, “that has aged remarkably well.”

The next step was ratification by the states. In a project conceived by Hamilton, who recruited Madison and Jay to the task, the trio dashed off eighty-five articles explaining the Constitution and published them in a New York newspaper. “The supreme example of improvisational journalism,” Ellis notes, the Federalist Papers were written to influence the ratification process in New York State, which was powerfully opposed to the Constitution.

While tumult, mischief, and wild cards abounded at the state ratifying conventions, some crucial recommendations were also advanced. At several conventions, delegates complained about the absence of a bill of rights and guarantees of the rights of conscience, trial by jury, and liberty of the press—objections that hit the mark and would receive redress in 1791 when the first ten amendments to the Constitution were ratified. Another accurate complaint—which was also backhanded recognition of the achievement of the quartet—was that the delegates in Philadelphia had radically exceeded their instructions by replacing rather than merely amending the Articles of Confederation.

After often searing debates, eleven states ratified the Constitution, and the quartet moved on to implement and institutionalize its national vision. Hamilton took the lead in ensuring that Washington would be the first president of the now United States, while, as treasury secretary, he devised strategies for a strong, diversified, dynamic economy. Jay was the Supreme Court’s first chief justice as well as the diplomat who negotiated the treaty bearing his name that averted renewed war with Great Britain, and the governor of New York who signed a law that, Ellis notes, put “slavery on the road to extinction” in the state. James Madison took the lead in drafting and steering through Congress in the summer of 1789 the Bill of Rights, our precious “secular version of the Ten Commandments,” as Ellis writes. But within a few years Madison would make a startling about-face. Opposing Hamilton’s financial plan and embracing a states’ rights interpretation of the Constitution, the “former champion of an ultranationalist vision,” in Ellis’s words, would found, with Jefferson, the opposition Republican Party.2

Like Benedict Arnold, the members of Joseph Ellis’s quartet had stared into the abyss and envisioned a chaotic future for their country possibly worse than if it had remained under British rule. Unlike Arnold, none would surrender to fear and self-interest. Instead they led Americans out of the hapless Confederation to a new beginning. The Quartet’s essential point is that “four men made history happen in a series of political decisions and actions that, in terms of their consequences, have no equal in American history.”

Over two centuries later, the quartet’s blueprint for government endures as the foundation of the oldest nation-size republic in modern history, an achievement that almost invites otherworldly explanations. Madison himself suggested that a pious man might perceive in the Framers’ accomplishment “a finger of that Almighty hand.” Yet it had not been their intention to write a sacred script. Thomas Jefferson was in Paris, not Philadelphia, in the summer of 1787, but Ellis gives him the last word. “Some men look at constitutions with sanctimonious reverence, and deem them like the ark of the covenant, too sacred to be touched,” Jefferson wrote in 1816. “They ascribe to the preceding age a wisdom more than human…. But I know also, that laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind.”

How ironic, Ellis concludes in his superb book, “that one of the few original intentions they all shared was opposition to any judicial doctrine of ‘original intent.’ To be sure, they all wished to be remembered, but they did not want to be embalmed.”

-

1

“What the French took from the Americans was their theory of revolution, not their theory of government—their cutting, not their sewing.” See John Dalberg-Acton, Lectures on the French Revolution, edited by John Neville Figgis (London: Macmillan, 1916), p. 32. ↩

-

2

The party founded by Jefferson and Madison was the Republican Party and not, as it is sometimes called, the Democratic-Republican Party. ↩