The most astonishing thing about The Arab of the Future, Riad Sattouf’s deft and devastating graphic memoir of his first seven years of life, is that he managed to write and publish it without getting killed.

Born in Paris in 1978, the son of a Syrian Sunni father and a mother from Brittany, Sattouf grew up in Libya, France, and Syria; his peripatetic childhood is the subject of his book.

But we know much more about Sattouf than his early life. We know that as an adult he moved back to France, drew a comic book about being circumcised when he was eight, made a satirical movie called Jacky in the Women’s Kingdom (set in a fictional Islamic country with reversed sex roles), and, until just before the massacre in Paris, worked for Charlie Hebdo, where he was the only cartoonist of Arab descent. In short, we know that Sattouf chose France over Syria. There he wrote and drew The Arab of the Future, a withering critique of his experiences of the societies he left behind, couching it all coyly in a picaresque graphic memoir told from a child’s point of view.

The first volume of this memoir, published initially in French as L’Arabe du Futur, won both the top award at the Angoulême International Comics Festival in 2015 and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for best graphic novel. (I served on the LA jury.) It focuses primarily on the relationship between little Riad and his father, Abdel-Razak, a professor with ambitions of bringing enlightenment, education, and unity to his fellow Arabs.

The second volume—in the running for a second Angoulême prize this year before Sattouf withdrew in protest because no female authors were on the list of nominees—focuses on Riad’s religious schooling in Syria.

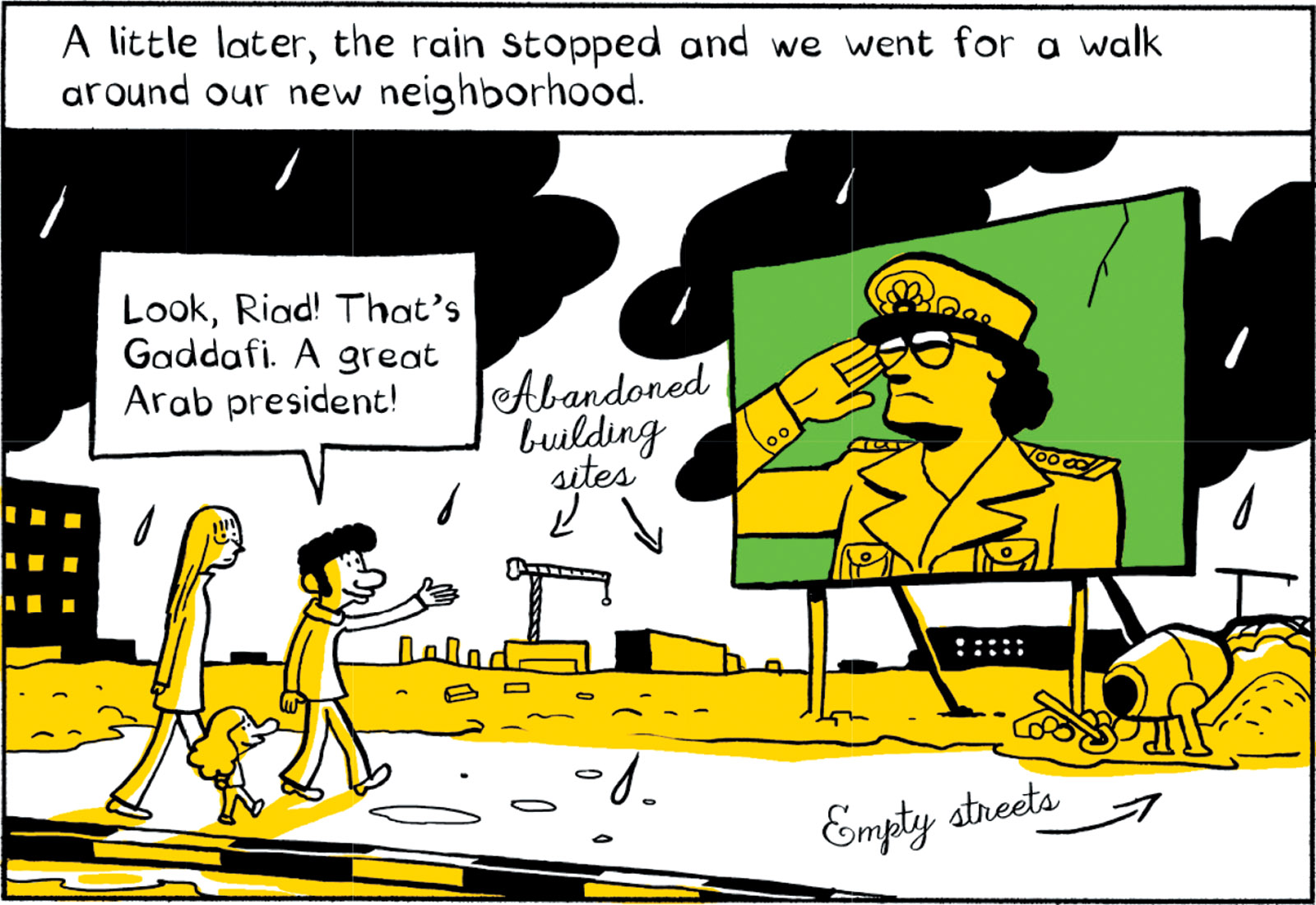

On one level, these two volumes are the detailed recollection, drawn with great economy and humor, of a preternaturally observant child as he is wrenched from Libya (which he denotes with a yellow wash) to France (a blue wash) and finally to Syria (a pink wash). Along the way we get a fine-grained, first-person account of the brutality of Syria under Hafez al-Assad and Libya under Muammar Qaddafi. But as the title suggests, The Arab of the Future can be read much more broadly. It suggests a story of two cultures, two civilizations, two ways of life—Europe vs. the Middle East, Occident vs. Orient. And it serves, in effect, as a close account and justification of Sattouf’s ultimate choice of France.

The look and sensibility of the comic are decidedly Western. It blends the gentle comedy of René Goscinny and Jean-Jacques Sempé’s Le Petit Nicolas (1959) with the zanier graphic style of Milt Gross’s New York comic strip That’s My Pop! (1933). Sattouf’s reportorial style is sardonic and yet matter-of-fact, reminiscent of Candide. His perspective is that of a wide-eyed, astonished French child puzzling out the world. It comes as no surprise to be told (in the second volume) that Riad learned French by reading Tintin, the bande dessinée starring a plucky boy who travels through strange and hostile lands.

Sattouf’s Frenchness was, it seems, largely chosen for him. Though half-Syrian, he apparently didn’t look it as a child. With flowing blond hair inherited from his mother, little Riad was taunted, pummeled, and despised as the ultimate other in Syria—a Yahudi, a Jew, even though he wasn’t. (Yahudi was the first word he learned in Syria, and it is a prime insult.)

In his self-caricature, Riad is a perfect target for bullies: a Little Lord Fauntleroy, flouncy and pampered, with a singsongy voice. His eyes, dots with curves under them, are wide open, his fluffy hair is a few fancy loops of the pen, and his mouth often gapes in amazement. His Arab cousins, by contrast, are depicted as small, adult-looking children with bumpy hooked noses, grim overbites, slicked-down black hair, and eyes that often slant sleepily down, topped by a straight angry brow.

Although Sattouf, in the expected Charlie Hebdo fashion, makes just about every person and group he depicts look gross and silly, his main subject in the first volume is his father, who stands out from the rest of his Syrian relatives. Abdel-Razak’s hair is curly rather than flattened, and he has a gentle, thoughtful look. His eyebrows suggest his emotions: they are either arched, in a hopeful way, or slanted in disappointment. He often behaves like a child. “Watch, I’m just like McEnroe!” he says, hitting a tennis ball over a roof. His son adores him: “My father was fantastic.”

Advertisement

Through Riad’s eyes we follow his father’s disturbing transformation. Abdel-Razak starts out as an enthusiastic pan-Arabist academic who is enamored of French freedoms and privileges (“They even pay you to be a student!”) and who has big dreams for the Arab people (“I would change everything in the Arab world. I’d make them…get educated and join the modern world”). But by the end of the first volume he has become a cynical apologist for dictators, believing that most Arab men are “lazy-ass bigots” in need of a strong, paternalistic boot to kick them into a better future.

What accounts for his change? In a word, humiliation. The drama of The Arab of the Future is watching Sattouf’s father’s personal disgraces pile up and waiting for them to ignite. Sattouf gives us a subtle visual clue to the blows to his father’s ego: “When my father felt humiliated,” he tells us, “he would stare into the distance with a little smile on his face and scratch his nose while he sniffed.”

We first meet Abdel-Razak a few years before Riad’s birth. He’s a student at the Sorbonne, the only member of his family who can read. We see him chatting with a young Frenchwoman named Clémentine. She tries to brush him off, but finally takes pity on him and his social cluelessness. They date; they marry. She types and heavily edits his thesis, “French Public Opinion Toward England, 1912–1914.” He becomes a professor; she becomes a mother.

Clémentine is a graphic cipher—a few strokes of long straight hair with bangs, a triangular nose, a short disapproving line for a mouth, an A-line smock, eyes often rolling in derision. We see her smile only a few times—once, for example, in volume two when she shares her love of the Galeries Lafayette with the rich wife of the chief of police in Homs. She rarely speaks, and when she does, her tone is skeptical and critical—a faint Greek chorus.

The child’s eyes, though, are primarily on his father. Around the time of the Camp David Accords, Abdel-Razak receives a teaching offer in the mail from Oxford University (to which Clémentine exclaims, “Classy!!!”). But Oxford spells his name wrong, and Abdel-Razak, irritated by this slight, decides instead to take an offer (with his name correct, and preceded by “Doctor”) to teach in Libya. Being a Libyan professor has an added attraction for him. It means he can pursue his dream of educating Arab men. And off the Sattoufs go on their first adventure.

In Tripoli, little Riad is impressed with the portraits of the handsome young Qaddafi that hang everywhere. But it is here that his father’s disappointments start accumulating. Being Dr. Sattouf, associate professor, is not the privileged situation he imagined. Like everyone else, his family gets food rations—mostly bananas, bread, rice, and Tang—by waiting in cutthroat lines (“Hurry up, dickhead!” “Move forward, bitch!”). Their apartment has leaks and no locks—in Qaddafi’s Libya of the 1980s there is no private property. And one day when the Sattoufs return from a walk, they find their house occupied by another family.

Despite the hardships, Abdel-Razak nonetheless enjoys being back in an Arab country. He especially likes listening to Radio Monte Carlo and reading to Clémentine from Qaddafi’s Green Book, which sets out the Libyan leader’s beliefs about everything from women (“affectionate, beautiful…fearful”) to race (“now it is the turn of the black race to dominate the world”). Although he’s horrified that Qaddafi thinks Arabs are part of the black race, he gets a kick out of the way he puts down the “white race,” the “Western dogs,” which, as Abdel-Razak teases his wife, include her: “That’s you!”

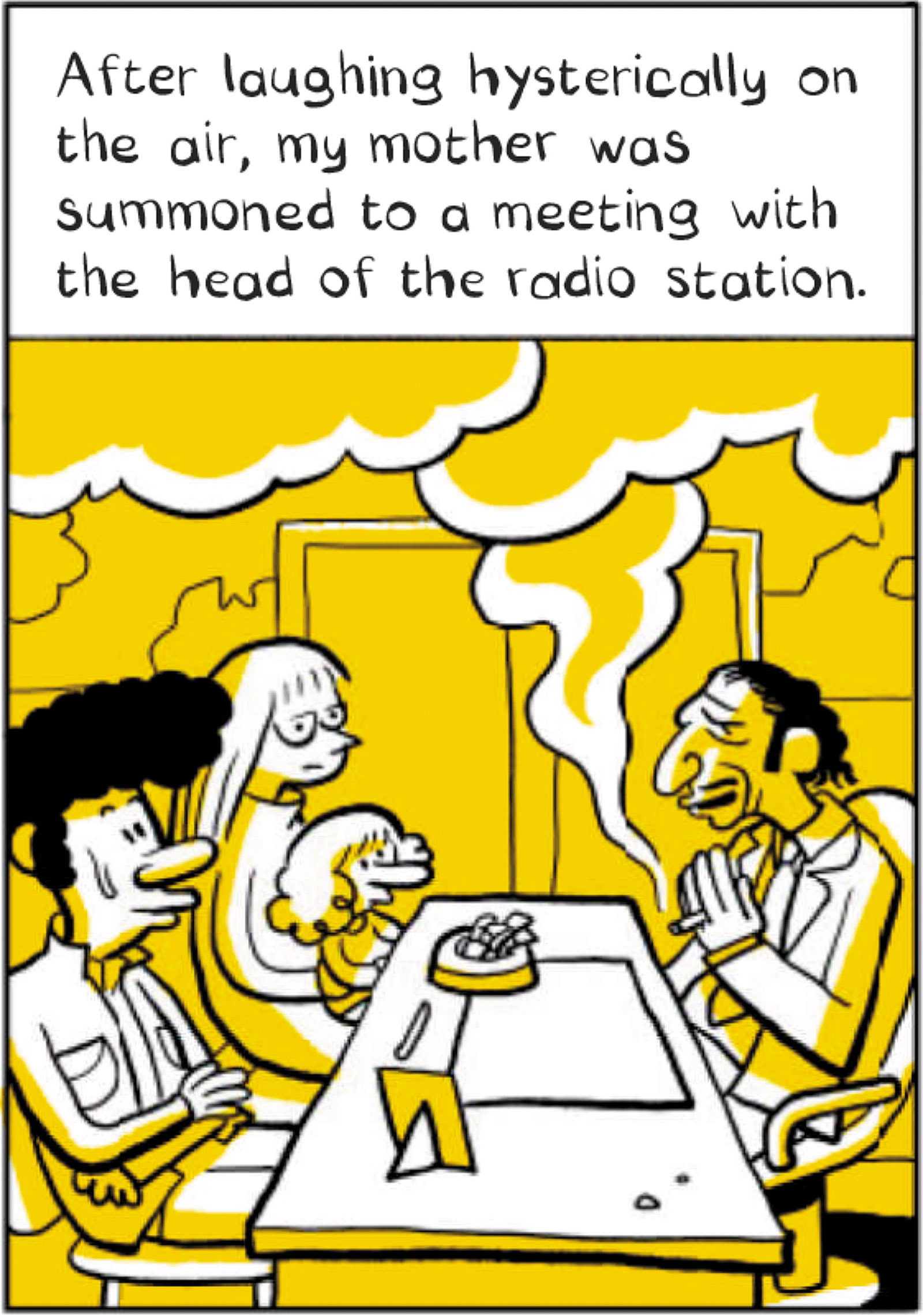

The long-suffering, eye-rolling Clémentine finds Qaddafi’s grandstanding ridiculous. She laughs off the insults dished out by her husband and Qaddafi, as if they’re just silly child’s play. In one episode, Abdel-Razak gets her a part-time job reading news in French on the radio. We watch Riad and his dad listening proudly to the car radio as she recites Qaddafi’s threats:

Colonel Qaddafi declared today that the provocations of the Western dogs would not go unanswered…. Speaking to France in particular, he stated that the Libyan army was ready to take on “America’s whore” at any moment.

At this point, Clémentine breaks into a laughing fit. Abdel-Razak rushes to the radio station to get her out of trouble, lying to the station manager that she laughed only because the papers she was reading from were stapled together wrong. Her job ends. The reader has no idea what this means to her or to little Riad.

Advertisement

Thanks largely to Clémentine’s capitulations both to Abdel-Razak and to the Libyan culture that she so clearly finds comically sexist and racist, the family runs smoothly. Little Riad has friends and a strong ego, seeing Qaddafi as a bigger version of himself: “Like me, he had lots of people admiring him and smiling at him all the time.” But when Qaddafi establishes a law requiring teachers to swap jobs with farmers, the Sattoufs’ residence in Libya comes to an abrupt end. Professor Abdel-Razak has no intention of being a farmer; it’s beneath him. So it’s “Good-bye Libya” and back to France.

While Abdel-Razak hunts for a new job, little Riad and his mother move to Brittany, where Clémentine’s mother lives. In France we see the boy beginning to make cultural comparisons and learning how to cope with people he doesn’t understand. He rides on the shoulders of his grandfather, a dirty old man who uses Riad to attract young women. And Riad takes walks on the beach at Cap Fréhel with his superstitious, ghost-fearing socialist French grandmother in her stylish glasses.

In France, Riad has a grand realization. While in class he notices that his fellow kindergartners, who are depicted as pig-nosed imbeciles, do nothing but babble and scribble. Although he himself can speak in full sentences and sketch caricatures of Pompidou, he decides to hide his abilities in order to get along. He babbles, he scribbles, he’s popular, he’s happy. Dissembling, he learns, is a great survival skill. And he enjoys practicing it.

The French chapter of Riad’s childhood comes to a quick halt when his father, who has supposedly been looking for work in France, finds a teaching job in Damascus instead. So it’s off to Syria.

The Sattoufs move to Ter Maaleh, near Homs, where Abdel-Razak’s extended family lives. The change is not to Riad’s liking. Portraits of Hafez al-Assad hang everywhere and Riad does not feel the kinship with Assad that he felt with the charismatic Qaddafi. “He wasn’t as handsome or sporty…and there was something shifty-looking about him. You couldn’t really see his eyes.”

And Abdel-Razak? Although he is delighted to be home again after seventeen years, it is here, in the heart of his family, where his greatest humiliation occurs. While he was away, his older brother sold a large share of Abdel-Razak’s family property without consulting him—the very land where he had dreamed of building his villa. “Land is everything,” he explains to Riad, sadly. “Nothing bad can happen to you when you have your own land.” Landless in his homeland, Riad’s father moves his family into a cold, empty house. We see the telling graphic gestures of humiliation: smile, sniff, scratch.

You might think that with a blow like this Abdel-Razak would pack up and leave or have it out with his brother, but neither happens. The professor who was thin-skinned enough to turn down a job at Oxford because his name was misspelled seems ready to endure any amount of insult and injury to himself or to Clémentine and Riad, as long as it comes from his own family and culture. He loves eating the foods of his youth and adores lying in his mother’s lap.

Clémentine and Riad bear the brunt of the misogynistic, violent, anti-Semitic world they’ve landed in. Kids stare at their yellow hair and call them filthy Jews. And Abdel-Razak, the once-enlightened professor, shares their gleeful loathing of Jews: “Worst race in the world.” We see Clémentine, like the other women in the family, dining on the gnawed bones and scraps the men have left behind. Her passivity is astonishing. Why does she stand for this? Sattouf has no answer. It’s almost as if she has escaped his satirical eye.

Little Riad is curiously impassive, even when it comes to his own struggles. We see his thuggish cousins try to beat him up every chance they get. And in volume two we meet his teacher—a brutal, beefy woman with a headscarf and a short skirt who carries a faux-jeweled handbag and a stick that she uses to beat students who don’t praise Assad loud enough or learn the suras of the Koran fast enough. Why doesn’t Riad protest? Why doesn’t he tell his parents just how terrifying his life is? Perhaps because he knows that his father will see his terror as a sign of his sissified French self.

The brutalities of life in Sattouf’s Syria, large and small, have a peculiar self-defeating flavor. On one occasion, for instance, the Sattoufs see a student take a drink at a water fountain, then take a piss, aiming straight for the spout. On another occasion, Riad brings his grandmother a bag of apples. His cousins cozy up to their grandma and take a bite out of each one, then toss them on the floor while staring down little Riad. The grandmother laughs and hugs the cousins closer.

Almost every gesture in the book seems an act of violence or spoilage meant to establish or reestablish order and hierarchy. In Sattouf’s Syria, power and prestige are constantly fought over, and any perceived weakness is reviled and often punished. In one scene a puppy is beaten to death with a shovel and then skewered on a pitchfork while everyone laughs. The strong and powerful are admired, even if they get (and keep) their status by victimizing others. Once, while lying on the hard floor in his djelaba, Abdel-Razak approvingly tells Riad the story of how Hafez al-Assad came to power and was able to brutalize the Sunnis—the Sattoufs’ own people:

He’s a clever man!… He’s an Alawite, so he’s not really a true Muslim, but still… He came from a poor family…[and with] hard work and determination, he was able to stage a coup and become president. He seized his chance. He gave all the important jobs to the Alawites and now we are their slaves!

In certain respects The Arab of the Future recalls Art Spiegelman’s groundbreaking graphic memoir Maus, the Holocaust cat-and-mouse tale that came out more than twenty-five years ago. Both deal with variations of brutality in the world and its repercussions in the family. They depict radically different kinds of anti-Semitism—one in Nazi-controlled Poland in the late 1930s and early 1940s, the other in the Middle East forty years later.

Both rely on one person’s memory (Spiegelman’s father’s memory of Auschwitz in the case of Maus, Riad Sattouf’s memory in the case of The Arab of the Future) to tell a traumatic history far larger than one person’s life. Both books focus on the damaged father as seen through his son’s wide-open eyes. And both largely ignore the mother and her story, though for very different reasons. In Spiegelman’s case, it was because his mother committed suicide and his grief-stricken father burned her Holocaust diaries. In Sattouf’s case, it’s because the mother he depicts is ridiculously recessive.

Yet despite the parallels between the two books, The Arab of the Future is more depressing. In Maus, the father, damaged as he is, is easy to sympathize with. His particular deformations—a crippling cheapness and an impulse to hoard—have understandable origins in his wartime experience and seem to imply nothing for the world’s future. By contrast, the deformations of Abdel-Razak conjure a deep pessimism—and not just for his family. If an educated pan-Arabist can turn out like him, what can we expect from others?

Abdel-Razak is not evil. He never beats his wife. He’s usually nice to his son. He’s just a man full of pent-up humiliation trying to get somewhere in the world, looking up to those with power or money, looking down on those he views as weak or beneath him—particularly women, blacks, Jews, and animals.

If Abdel-Razak were seen by Sattouf as nothing more than a damaged father in Syria, The Arab of the Future would not be nearly so bleak. But wherever you turn in Sattouf’s Syria, you see the father’s values magnified and put into action. Poor children are beaten by their teachers for not having the right books or uniforms in school. Birds too small to eat are shot to smithereens. Women are left to eat men’s leftovers. There is hardly anyone depicted in the book, child or adult, who doesn’t somehow reflect these values, whether as a victim or a bully.

Sattouf says he is not a political cartoonist. When he was at Charlie Hebdo, from 2004 to 2014, he never caricatured Muhammad, Jesus, Buddha, Moses, or the pope. Instead, he drew a bitter comic strip that was titled La Vie Secrète des Jeunes (“The Secret Life of Youth”), apparently based on teenage conversations, often stupid, absurd, or gross, that he overheard on the streets of Paris. He quit in late 2014, he said, not for any political reason but because he found French teenage life too dispiriting.

As for The Arab of the Future, he told Jeune Afrique last year that it is just “a description of everyday life…. I did not want to make a political book…I’m embarrassed when an artist engages in politics.” The Arab of the Future, despite its general title, Sattouf seems to suggest, does not set out to capture Arab character or pathology, or to diagnose an Arab Problem. And it certainly does not pretend to offer anything like a history of Syria or Libya in the 1980s, or an explanation of how that relates to the chaos today. For example, there is no mention of the movements to resist Hafez al-Assad or his violent responses to them.

There is, however, one glimmer of protest in the book. In the second volume of The Arab of the Future, Sattouf introduces us to Abdel-Razak’s niece, Leila, a thirty-five-year-old widow, who takes an interest in little Riad’s art and teaches him one-point perspective and how to turn his sketch of Pompidou into a caricature of Assad. It is an episode that, for a moment, makes the reader feel a pang of hope.

But then, in the book’s most shocking scene, we see her smothered to death by her own father and brother. A horrified Riad—we watch the murder as he imagines it—listens to the story through his parents’ bedroom door. He hears his father arguing with his mother that Leila, because she was pregnant without being married, had to be killed to save face for the family. The next morning no one speaks of this “honor killing.” Life goes on as if nothing has happened. The spark of resistance has been snuffed out.

Sattouf has been praised on both the left and right in France. Maybe this is because his Candide-like deadpan reactions allow some readers to believe he is blaming the current chaos in Syria and Libya on the violent and intolerant culture of dictatorship while allowing others to believe he is blaming Arab culture more generally. But whatever interpretation might be drawn from his work, it is most basically a personal and family history.

When I finished reading these two volumes, I was struck by Sattouf’s precarious perspective and I feared for his life. If the book is true to his experience, it’s amazing that the little boy who grew up with the father and the family he shows us has turned out to be a man who could write The Arab of the Future, a book that is both sensitive and biting. He has survived the publication of these two volumes and a third has just been published in France. Clearly, at least one Arab of the future is Riad Sattouf himself. And that’s as good an ending as one could possibly hope for.