1.

The first poem in this substantial selection of the work of the St. Lucia–born poet Derek Walcott was written when he was only eighteen. It initially appeared in a privately printed volume entitled 25 Poems (1949), a self-publishing venture subsidized by Walcott’s widowed mother (who worked as a seamstress and a teacher) to the tune of $200—a stake she eventually recouped after the young poet sold enough copies to friends to break even. The poem is set at twilight, and opens:

The fishermen rowing homeward in the dusk,

Do not consider the stillness through which they move.

So I since feelings drown, should no more ask

What twilight and safety your strong hands gave.

The first two lines are lucid enough, but the second two seem themselves overtaken by dusk, a little murky and hard to make out. Unlike the fishermen who are so involved in the task of rowing homeward that they have no time for emotional or aesthetic responses to the evening stillness through which they move, the poet presents himself as overwhelmed by feelings—as drowning in them, rather than rowing through them. Or might his feelings drown someone else? Or might it be the feelings themselves that drown? The phrase could be parsed all sorts of ways.

Does he, one wonders, envy the fishermen’s stoical lack of reflectiveness, or are the drowning feelings introduced as a way of signifying the gulf between their primitive hand-to-mouth concerns and his superior, educated, impassioned consciousness? And whose are the “strong hands”? Is he telling himself not to ask because the question would widen the gap between himself and the fishermen? Perhaps all that is unambiguously clear from these two lines is that the young Walcott has been reading the young Auden.

Indeterminacies of this kind clearly befit a poem that takes place in the gloaming. In Walcott’s later writings twilight often assumes a more particular figurative significance. In the 1970 essay “What the Twilight Says” he describes how an Antillean dusk can transform a slum into a thing of beauty:

Deprivation is made lyrical, and twilight, with the patience of alchemy, almost transmutes despair into virtue. In the tropics nothing is lovelier than the allotments of the poor, no theatre is as vivid, voluble, and cheap.

The stab of irony in “cheap” signals the unease that so often afflicts Walcott when he considers the gap between himself and the Caribbean poor. As in “The Fishermen Rowing Homeward…,” twilight is depicted in this essay as prompting reflections on his relationship with his less self-conscious compatriots:

Years ago, watching them, and suffering as you watched, you proffered silently the charity of a language which they could not speak, until your suffering, like the language, felt superior, estranged. The dusk was a raucous chaos of curses, gossip, and laughter; everything performed in public, but the voice of the inner language was reflective and mannered, as far above its subjects as that sun which would never set until its twilight became a metaphor for the withdrawal of empire and the beginning of our doubt.

Certainly the language used by the teenage poet is “superior, estranged” from that of the streets, as well as “reflective and mannered,” but the obscurities that shroud a poem such as “The Fishermen Rowing Homeward…” are here linked to Walcott’s dawning, or rather crepuscular, understanding of his postcolonial situation. Empire’s evening becomes evening’s empire, and culminates in “our doubt,” a doubt, he goes on to insist, that also makes possible its seeming opposite, a “prodigious ambition”:

The writers of my generation were natural assimilators. We knew the literature of empires, Greek, Roman, British, through their essential classics; and both the patois of the street and the language of the classroom hid the elation of discovery. If there was nothing, there was everything to be made. With this prodigious ambition one began.

The distinctive conditions that shaped Walcott’s outlook and poetic idiom often verge on the paradoxical, but the contradictions they engender lose some of their angularities and hopelessness when viewed, like a Caribbean slum, at the lyrical moment of twilight. Unlike his fellow Caribbean poet Kamau Brathwaite, who sought to develop a poetry that rejected the language of the “essential classics” and instead attempted to capture “the patois of the street” in all its “raucous chaos of curses, gossip, and laughter,” Walcott set himself the task of learning all he could from the “literature of empires” in order to create a Caribbean poetry as rich and rewarding and viable as the canonical works written in Greek, Latin, and English that formed the staple of his school curriculum.

Inevitably, one of the dominant themes of this poetry is the investigation that it undertakes into the historical events that led to, say, Walcott’s studying European classics in an English-speaking school on an island many thousands of nautical miles from Europe; or to his father—who died when Walcott was only a year old—being named after the county that Shakespeare was born in, as a revenant Walcott senior informs his son in Chapter XII of his Dantesque book-length poem Omeros (1990):

Advertisement

I was raised in this obscure Caribbean port,

where my bastard father christened me for his shire:

Warwick. The Bard’s county.

Warwick Walcott died on Shakespeare’s birthday, from a disease that resembled the ear infection that killed Hamlet’s father, literary coincidences that the bookish pair enjoy a chuckle over: “Death imitating Art, eh?”

Like all writers who academics these days interpret through the lens of postcolonial theory, Walcott juggles, conjugates, and reconfigures the dominant terms of Caliban’s spirited riposte to Prospero in the play in which Shakespeare most directly confronts issues of colonization, The Tempest: “You taught me language, and my profit on’t/Is, I know how to curse.” Language, profit, curse. What profit, Walcott’s poetry often asks, is there in cursing, however effectively the language one has been taught is deployed? In “A Far Cry from Africa,” composed in his late twenties, he wonders:

Where shall I turn, divided to the vein?

I who have cursed

The drunken officer of British rule, how choose

Between this Africa and the English tongue I love?

Betray them both, or give back what they give?

The poem was prompted by the savage suppression by the British authorities of the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya in the late 1950s, and is the first in this volume in which Walcott specifically articulates the problems posed by his hybrid cultural heritage and ancestry (his grandfathers were white, his grandmothers descendants of slaves brought from Africa). As in “The Fishermen Rowing Homeward…,” a shadowy ambivalence rescues him from what seems like an impossible question: What does it mean to “give back what they give”? Under the sign of “curse” it implies a returning of unwanted gifts, but under the sign of “profit” it can be read as an absorption and transformation of their traditions into a new poetic style to be, at some point, made available to both. Like twilight, this second possible meaning softens the contours of the dilemma Walcott diagnoses, allowing language to contain both curse and profit.

Of course not all poetry written in European languages is complicit with the imperatives of conquest and slavery. In the poetry of Walt Whitman and Pablo Neruda and Aimé Césaire, Walcott discovered a “tough aesthetic” that “neither explains nor forgives history”; their “vision of man in the New World,” he declared in a 1974 essay, “The Muse of History,” “is Adamic.” This Adamic vision, he goes on to assert, makes possible an escape from the roles of master and slave, or ex-master and ex-slave, by opening our eyes to the “awe of the numinous”: it is the

elemental privilege of naming the New World which annihilates history in our great poets, an elation common to all of them, whether they are aligned by heritage to Crusoe and Prospero or to Friday and Caliban. They reject ethnic ancestry for faith in elemental man. The vision, the “democratic vista,” is not metaphorical, it is a social necessity.

Crusoe serves as ancestor for Walcott in two mid-Sixties poems, “Crusoe’s Journal” and “Crusoe’s Island” (both collected in The Castaway of 1965), where Defoe’s hero offers a means of defining this Adamic language, in which “even the bare necessities/of style are turned to use.” This involves jettisoning the “dead metaphors,” to borrow a phrase from the book’s title poem, and evolving a language that emerges from the need to shape New World realities into workable forms, as Crusoe used the tools he salvaged from the wreck to survive on his island, and at the same time created a prose “as odorous as raw wood to the adze”:

out of such timbers

came our first book, our profane Genesis

whose Adam speaks that prose

which, blessing some sea-rock, startles itself

with poetry’s surprise,

in a green world, one without metaphors….

[“Crusoe’s Journal”]

Complicating this celebration of New World self-reliance is the fact that Walcott has to borrow a character invented by an eighteenth-century English novelist, here figured as a New World Adam writing a profane Caribbean Genesis, in order to voice it. Yet Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe is as much an aspect of Walcott’s St. Lucia as the sea-rock that both Crusoe and Walcott find themselves blessing. In other words, what most strikingly differentiates Walcott’s New World poetics from those of Whitman or Neruda or Césaire is his insouciant, or pragmatic, willingness to make use of characters and traditions and idioms from Europe just as long as he feels that they can be adapted to the cultural needs of the present time and place. If they end up being “regifted” to their countries of origin, all the better.

Advertisement

Hence his blithe and daring appropriation of Dante and Homer in Omeros (which is written in terza rima and features characters called Achille, Hector, and Helen), and his happy incorporation of the voices of other poets in his early work, where familiar figures slide in and out of view like so many strollers glimpsed in an evening passeggiata: Yeats (“Ruins of a Great House”—“and pacing, I thought next/Of men like Hawkins, Walter Raleigh, Drake” could almost be in a book of Yeats pastiches), Eliot (“No tenant sound of bird in the dry season”), Auden, Dylan Thomas, Louis MacNeice….

Walcott is an unashamed adept of the mimicry that (as Homi Bhabha argued in an influential essay of 1987) plays a crucial part in the formation of postcolonial identity. By the mid-Sixties the axis has shifted to East Coast American poets, and in particular to the Lowell of For the Union Dead. Anyone looking to chart Lowell’s influence on his admirers could do worse than compare Sylvia Plath’s “Ariel” with Walcott’s “The Castaway”; both were published in 1965, and they forge from the Lowellian language many strikingly similar effects.

There is a carefree, even gleeful aspect to Walcott’s openness to the idioms of others, perhaps best glossed by the phrase he uses in “What the Twilight Says”: “the elation of discovery.” And it is his perception of the absence of what might be called a “native tradition” that licenses his hospitality to whatever seems to him likely to enable him to contrive one:

Colonials, we began with this malarial enervation: that nothing could ever be built among these rotting shacks, barefooted back yards, and moulting shingles.

The almost overwhelming abundance of Walcott’s oeuvre, its riotous and “prodigious ambition,” emerges from his sense that he has nothing to mar, and nothing to lose. The ideal of the Adamic vision allows Walcott’s use of the texts of others to develop into something wholly different from both modernist collage, as practiced by, say, Eliot and Pound as a form of cultural critique, and its heir, postmodernist collage, which splices together a multiplicity of dictions in order to lay bare the illusions of subjectivity. Walcott’s “hybrid muse,” to borrow the title of Jahan Ramazani’s excellent 2001 study of postcolonial poetry in English, proceeds instead by what Keats called “a fine excess,” a prodigal layering of voices and effects and references focused only by the quest to adapt existing traditions to present needs. “So from this house,” he writes in “Crusoe’s Journal,”

that faces nothing but the sea, his journals

assume a household use,

We learn to shape from them, where nothing was

the language of a race….

The distance between “household use” and “the language of a race” neatly captures the scale of Walcott’s ambition. From Homer’s Iliad to Joyce’s Ulysses, it is the epic, in its various guises, that has most fully assumed the role of binding together a linguistic community by recounting historical and mythical narratives. For Walcott, who grew up speaking English in a predominantly Francophone Caribbean society, in which also flourished a range of different patois, the language of his race is not easy to pin down. But nor was it for Joyce, whose Gabriel Conroy is berated by an Irish Nationalist in “The Dead” for not learning Gaelic, rather as Walcott has on occasion been attacked for writing poems that reflect his reading of Shakespeare and Wordsworth and Yeats rather than the languages spoken around him.

Omeros, his most ambitious attempt at an epic, does make occasional use of nonstandard English. “This is how, one sunrise, we cut down them canoes,” it opens, a foundational moment narrated by Philoctete to a horde of tourists. Rather than the building of an imperial city, as in, say, the Aeneid, it is the heroic chopping down of the towering trees called laurier-cannelles and the fashioning from their trunks of the seaworthy canoes that enable Philoctete and Achille and Hector to fish the Caribbean, which Walcott presents as the primary crucial act. He nevertheless, even in the first chapter, makes the reader aware that the island was called Iounalao (“where the iguana is found”) by its original inhabitants, the Arawaks, of whom only pottery traces remain. The motif of the iguana keeps appearing throughout the poem in order to remind us of the prehistory of St. Lucia.

Omeros is well over three hundred pages long, and “owing to limitations of space,” a note on the contents page tells us, is entirely absent from this volume. That’s a shame, and unnecessary really, since Omeros is a compendium-style poem from which it’s easy to lift self-contained excerpts, and its epic scope generated some of Walcott’s finest writing. None of his four more recent collections—The Bounty (1997), Tiepolo’s Hound (2000), The Prodigal (2004), and White Egrets (2010), all represented in this new selection—seems to me to achieve as effective a balance between descriptive exuberance and an overarching set of narratives as that developed in Omeros.

2.

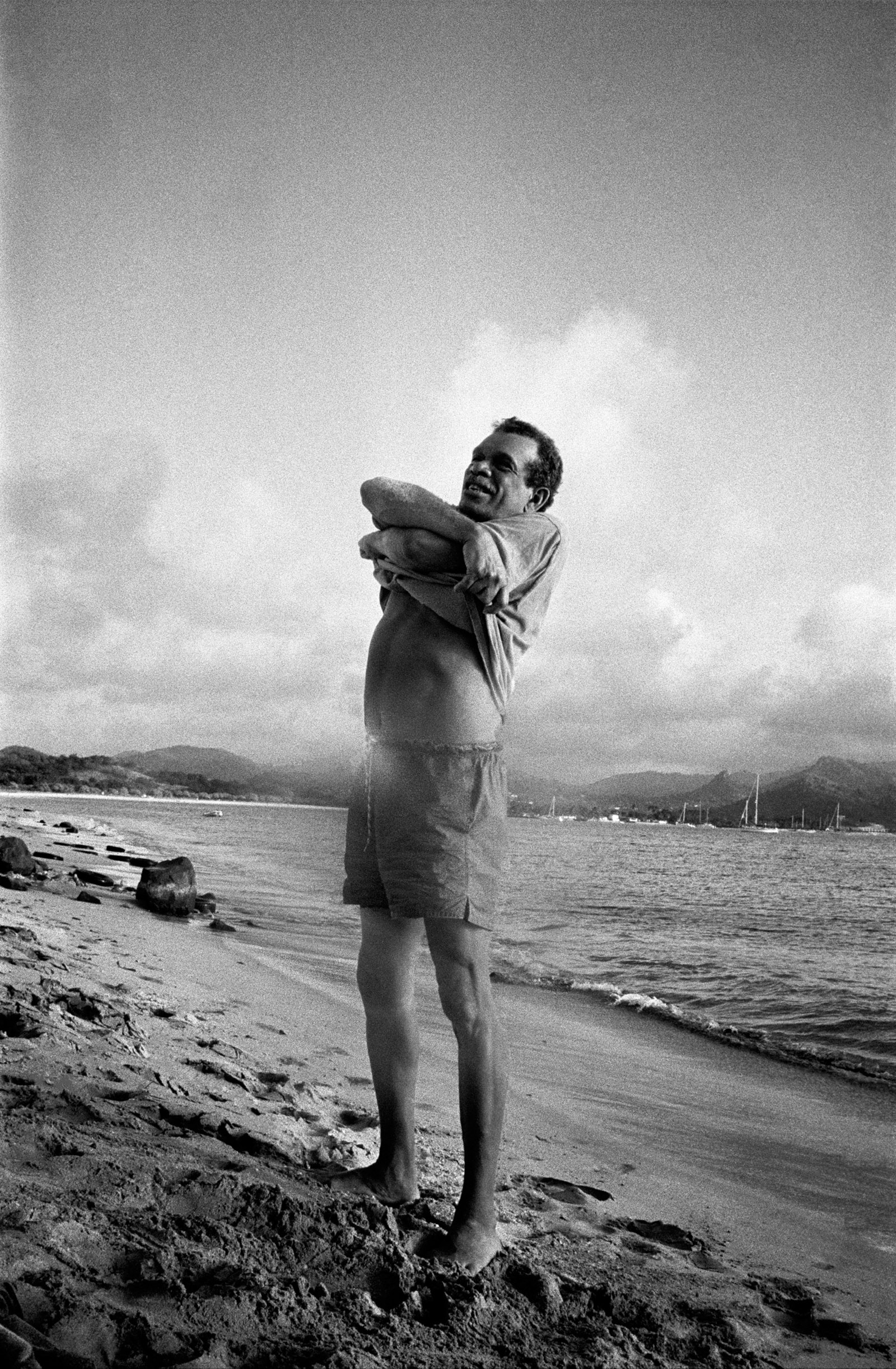

Walcott spent most of his twenties and thirties—during the 1950s and 1960s—in the Caribbean, attending university in Kingston, Jamaica, and then earning a living as a teacher and journalist there, before moving to Trinidad in 1953. He spent 1958 in New York on a Rockefeller Fellowship to study drama, the first of a series of sojourns in America, where a substantial number of the poems in the second half of this book are set.

In 1981 he was appointed to a post teaching creative writing at Boston University, and began to appear more regularly at international arts festivals. The title of the collection he published the year after he took up his appointment at BU, The Fortunate Traveller (1982), signals his embrace of an itinerant life, and many subsequent volumes might be characterized as offering a kind of poetic travelogue; title after title advertises a verse description of some city or locale, and poem after poem delivers on the promise: “Old New England,” “Greece,” “The Arkansas Testament,” “Spain,” “Italian Eclogues,” “A London Afternoon,” “In Amsterdam”…

“And have we room,” Elizabeth Bishop asks in “Questions of Travel,” “for one more folded sunset, still quite warm?” to which Walcott’s answer is invariably yes. The extraordinary range of cities and landscapes, from Cape Cod to the Alps, from Belfast to Venice, from Chicago to Pescara, depicted by Walcott during the second half of his poetic career brings to mind the astringent comments on poetry and travel made by Philip Larkin in an interview of 1979. Asked if he’d like to visit China, he replied:

I wouldn’t mind seeing China if I could come back the same day. I hate being abroad…. I think travelling is very much a novelist’s thing. A novelist needs new scenes, new people, new themes. The Graham Greenes, the Somerset Maughams, travelling is necessary for them. I don’t think it is for poets. The poet is really engaged in recreating the familiar, he’s not committed to introducing the unfamiliar.

I doubt many would agree with this, especially if one considers the role that travel played in the development of, say, Milton or Wordsworth or Byron or Browning.

In a brilliant essay on Larkin collected in What the Twilight Says, Walcott describes his work as being perfectly made for “household use,” to quote again the phrase from “Crusoe’s Journal”: Larkin’s poems are figured by Walcott as “useful and private,” “as familiar as a bunch of keys. One picked them up as casually; they were small, shining, and slipped easily into the pocket of memory.” Walcott’s own travel poems, on the other hand, often strike me as almost the opposite of this: leisurely and public, motivated by the need to confront the unfamiliar, often a little opaque, not that easy to remember.

A typical instance of Walcott’s descriptive travel mode is the opening stanza of part 2 of The Prodigal; this passage also exemplifies how the multiple layering that Walcott evolved in response to the “malarial enervation” diagnosed in “What the Twilight Says” risks dazzling the reader with overload, with too many details and images—pushing Keats’s “fine excess” toward the overwritten:

Chasms and fissures of the vertiginous Alps

through the plane window, meadows of snow

on powdery precipices, the cantons of cumuli

grumbling or closing, gasping falls of light

a steady and serene white-knuckled horror

of speckled white serrations, inconceivable

in repetition, spumy avalanches

of forgetting cloud, in the wrong heaven—

a paradise of ice and camouflage

of speeding seraphs’ shadows down its slopes

under the metal, featherless wings, the noise

a violation of that pre-primal silence

white and without thought, my fear was white

and my belief obliterated—a black stroke

on a primed canvas, everything was white,

white was the color of nothing, not the night,

my faith was strapped in.

Phew! One marvels at the skill taken to pull off such a feat of rhetoric—without really wanting to read a lot more of it. Teetering on the verge of pastiche, it summons up the ghost of some of Hart Crane’s more high-flown apostrophes when evoking the mysteries of aviation—“corymbulous formations of mechanics” or “O sinewy silver biplane, nudging the wind’s withers!” The elaborate literary formulations on display in such a passage are in many ways even more “mannered” than those of “The Fishermen Rowing Homeward….”

There is a certain irony in Walcott’s writing so much poetry over the last few decades from the perspective of a globetrotting sightseer, since one of the principal threats to St. Lucia’s sense of cultural independence identified in Omeros is its economic reliance on the tourist industry. The tourists to whom Philoctete tells the story of the felling of the trees and the making of the canoes are trying to take “his soul with their cameras.” We are pointedly informed that although he is willing to show them the scar on his leg from a wound made by a rusty anchor, he will not explain to them its cure: “‘It have some things’—he smiles—‘worth more than a dollar.’”

If there’s a symbol of evil in Walcott’s poetry, it is the tourist cruise liner. “The Fisherman Rowing Homeward…” concludes with lines that are mainly metaphorical, but can also be construed as the first of his attacks on the damage wrought on traditional Caribbean lifestyles by the cruise industry:

And the secure from thinking may climb safe to liners,

Hearing small rumors of paddlers drowned near stars.

One of the most impressive sections of Omeros describes a “liner as white as a mirage,/its hull bright as paper, preening with privilege.” This liner’s

humming engines spewed expensive garbage

where boys balanced on logs or, riding old tires,

shouted up past the hull to tourists on the rails

to throw down coins, as cameras caught their black cries…

This sight in turn evokes a childhood memory of watching, from the same Castries wharf, women carrying hundredweight baskets of coal on their heads up the steep gangplank of “a liner tall as a cloud,” like innumerable “ants up a white flower-pot.” The sight of them, the ghost of his father tells him, “showed you hell, early.” Warwick goes on to characterize his son’s poetic toil as analogous to the heavy lifting and carrying accomplished with noble fortitude by these women:

Kneel to your load, then balance your staggering feet

and walk up that coal ladder as they do in time,

one bare foot after the next in ancestral rhyme.

As in response to Yeats’s assertion in “Adam’s Curse” that writing poetry is more onerous than scrubbing a kitchen pavement or breaking stones in bad weather, one may question the comparison between heavy manual work and sitting at a desk composing verse, but the antics of the boys diving for coins tossed by tourists and the grim labors of the women carrying coal up a gangplank for one copper penny per hundredweight basket vividly embody St. Lucia’s marginalized status in the global economic hierarchy.

Cruise liners appear at the conclusion of the last poem in this book too, along with various other kinds of vessel and a final deployment of Walcott’s all-time favorite rhetorical maneuver, which involves intertwining what he sees with a simile or metaphor drawn from writing (“crows/like commas,” “West of each stanza/that the sunset made,” etc.). This volume offers dozens of examples of this particular trope. Sometimes it’s used brilliantly, as in the final stanza of the wonderful short lyric “To Norline” (Norline Metivier was Walcott’s third wife; the poem was written after their divorce):

and someone else will come

from the still-sleeping house,

a coffee mug warming his palm

as my body once cupped yours,

to memorize this passage

of a salt-sipping tern,

like when some line on a page

is loved, and it’s hard to turn.

Other times you simply wish an editor had put a blue pencil through the passage in question. Walcott’s fondness for this gambit can be seen, I think, as a symptom of his “prodigious ambition,” of the confidence that he feels in poetry’s power to map itself onto the world. “This page is a cloud,” opens the almost-sonnet (it’s thirteen lines long) that closes White Egrets:

a line of gulls has arrowed

into the widening harbor of a town with no noise,

its streets growing closer like print you can now read,

two cruise ships, schooners, a tug, ancestral canoes,

as a cloud slowly covers the page and it goes

white again and the book comes to a close.

This repeated flipping between the physical world and the world of words seems motivated by Walcott’s love of the lyrical confusions of evening’s empire; in the liminal space created, as the cloud covers the page, we are invited to ponder the absence of a sonnet’s fourteenth line, to hear, or imagine, what the twilight says.

This Issue

November 10, 2016

Inside the Sacrifice Zone

Why Be a Parent?

Kierkegaard’s Rebellion