Mark Danner

All American elections tend to be touted as historic, for all American culture tends toward the condition of hype. Flummoxing, then, to be confronted with a struggle for political power in which, for once, all is at stake. We have long since forfeited the words to confront it, rendering superlatives threadbare, impotent. No accident that among so many other things Donald J. Trump is the Candidate of Dead Words, spewing “fantastic” and “amazing” and “huge” in all directions, clogging the airtime broadcasters have lavished upon him with a deadening rhetoric reminiscent of the raving man hunched beside you on the bar stool. “This country is a disaster.” “We’re in big trouble, folks.” “Our leaders don’t know what they’re doing.” Or his favorite declarative closer to those 140-character Twitter dispatches that form the campaign’s anti-poetry, “Sad!” It is our loss that Mario Cuomo, who famously offered that “you campaign in poetry; you govern in prose,” is no longer here to enlighten us about in what, if we campaign in tweets and dead superlatives, we are destined to govern.

We have no idea. While on one side we have a vague conception of what our future politics might be—a professedly progressive government of familiar faces and uncertain success, dogged to a greater or lesser degree by congressional opposition and revivified scandal—on the other we have terrifyingly little notion. For the animating element of the Trump campaign, beyond its self-propelling cycle of insult and crass entertainment, is not a positive political program—renegotiating trade deals or imposing a Muslim immigration ban or even building an “impenetrable and beautiful” Mexico wall—but a kind of furious and exasperated nihilism about government as it exists and the broader discredited elite from which it emanates: the corruption, the back-scratching, the self-dealing.

The most powerful emotion one feels at a Trump rally is a great bellowing lust to scrub thoroughly the Augean stables and to entertain raucously while shoveling out the shit.1 Throw them out! And the “them,” it should be emphasized, is proudly nonpartisan: the elite of the Republican Party counts as corrupt as that of the Democratic; longtime conservative newspapers are no less representatives of the “lamestream media” than the liberal New York Times.

Thus their candidate may declare that he might refuse to support NATO members in the Baltics or that he might offer nuclear weapons to the Japanese or South Koreans or apply waterboarding or something “a hell of a lot worse” to any captured terrorist. Whatever principle of the postwar Pax Americana he blithely shatters, and however many “national security leaders” from Republican administrations issue yet another condemnation of Trump and pledge to vote for Hillary, this will do little but reassure his supporters. That their candidate offends, disgusts, appalls the elite and won’t seriously apologize for it, that, as we have seen, he refuses to back down from the grossest violations of “politically correct” discourse in matters of race and sex, reaffirms that he, unlike all who have come before with their pallid pledges to “change Washington,” might actually do it. The shocked, disgusted elite is not only an object of scorn and derision but an affirmation of his strength. And he is all about strength, a kind of embodied id.

It is this darkly echoing “no!” at the heart of the Trump campaign, joined to its permanent revolution of insult and entertainment, that makes the present moment so vertiginous. We have lived moments before in which the heretofore unquestioned political lineaments of our world seemed rendered suddenly unstable, fragile, mutable. But these were moments of sudden violence—the world-altering rifle shots of 1963 and 1968; the planes and towers of 2001—not a slow-motion reality freak show in which what we had believed to be the remaining sacrosanct conventions of our politics were thoroughly and methodically trampled underfoot like so many discarded banners and placards, so many punctured balloons…

What are these bedraggled balloons? Truth, say? Facts? An attention to qualifications? A respect for experience? An attending to…rationality? It is true that Trump appalls with the baroque flagrancy of his vanity and self-obsession, like those neurotics we sometimes meet whose obsessions are so self-assertive that we seem to be staring directly into their skulls: as with them, the forced intimacy of the encounter can border on the nauseating.

But perhaps this is all sanctimonious illusion. Perhaps we are seeing punctured here misconceptions long entertained, perpetuated through lack of challenge. Ronald Reagan, of whom Trump in some ways is a caricature,2 maintained a decidedly capricious relationship with the truth. George W. Bush’s self-styled imperial administration declared that “we’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality….” Is Trump simply thrusting full into our faces currents we have struggled to ignore? The “plunge of civilization into this abyss of blood and darkness,” wrote Henry James at the outset of World War I,

Advertisement

so gives away the whole long age during which we have supposed the world to be, with whatever abatement, gradually bettering, that to have to take it all now for what the treacherous years were all the while really making for and meaning is too tragic for any words.

Is Donald J. Trump really what the whole long age was gradually making for and meaning? That a reality television star and businessman con artist devoid of public office experience and proudly ignorant of public policy, of braggadocious and offensive and unstable character, given to the most bald-faced race-baiting and misogyny and demagoguery, could nonetheless be elected by our fellow citizens president of the United States?

It should be observed that this is not a question that will be answered by the election itself. If Donald J. Trump is not elected president of the United States on November 8, we will owe this not to some triumph of the superior American system or to the eloquent presentation of a progressive alternative but to the fact that this singularly offensive man offended too many voters, especially white, college-educated women. It will not be because he was rendered unelectable by virtue of his lies and race-baiting and immigrant-bashing and demagoguery.

On the contrary. Trump embodies grisly aspects of our politics that are not new but that, on him, are starkly illuminated. What are these? That much of our politics in this increasingly diverse country pivots on the hateful fulcrum of race, of racial fear and xenophobia and antagonism toward the Other, and that this has only grown in power and ugliness since the rise of Barack Obama and his coalition. That in vital matters of gender and sexuality and marriage much of the politics of the presiding culture is furiously rejected by a significant minority of the country as a “politically correct” and immoral imposition. That in the aftermath of a severe economic crisis—and after decades of economic stagnation for most Americans—tens of millions of voters feel so abandoned by the system that they offer their full-throated cheers to a candidate pledging to wholly dismantle it and put “in jail” his opponent. That the electoral system as it has evolved over that time and especially in the wake of such decisions as Citizens United has become starkly, shabbily, and spectacularly corrupt. And finally that entertainment and money in the grossest sense play a far more important part in our politics than any attention to public policy, and that the commercial press, particularly the broadcast press, battens on that reality to an increasingly shameless degree.

In the wake of Donald Trump all these tendencies will persist and perhaps—during a Clinton presidency—flourish, awaiting the next opportunistic figure who demonstrates the ruthlessness and skill to exploit them, and the steady-handedness, perhaps, to avoid needlessly alienating quite so much of the electorate. It is a grim and echoing reality, and one that we ignore at our peril, that many of Trump’s most egregious faults as a candidate are by no means intrinsic to his politics. He could be playing the ragged John the Baptist to a less outrageous and thus more dangerous savior to come.

Pondering the rise of the demagogue Cleon, Aristotle observed that he “was the first who shouted on the public platform, who used abusive language and who spoke with his cloak girt around him, while all the others used to speak in proper dress and manner.” Trump has raised the cloak. Whoever becomes president, it is unlikely to be lowered again in our lifetimes.

Andrew Delbanco

After this dark season, will there be light? All depends of course on whether the lying, ranting, self-adoring con man is kept out of the White House. Since his private “boasts about sexual assaults” (John McCain’s phrase) went public last week, the menace appears to be fading—but even if the nightmare comes to an end, where will we find ourselves when we awake?

Nowhere familiar, I think. Could anyone have predicted that the right-wing Glenn Beck, in a friendly interview with Lawrence O’Donnell on the left-leaning network MSNBC, would liken the Republican nominee’s campaign chief to Lenin, by which Beck means “a destroyer of everything”? America’s political categories have been scrambled beyond recognition—and that just might turn out to be a good thing.

So far, the shock is most evident among Republicans trying to figure out how to renounce their monstrous candidate without enraging his supporters—a task made harder by his crude but controlled (for him) performance in the second debate, designed to fire up his loyalists. Republicans are doing the best rendition of a disintegrating party since the Whigs came apart over slavery on the eve of the Civil War. The “Alt-right” and Tea Party were already creating pressures within when Donald Trump invaded the party from without by appointing himself, in Charles Blow’s phrase, “Grand Wizard of Birtherism.” With measureless cynicism and a showman’s talent, he tapped not only into the cesspool of hatred against President Obama but also into the anger of the Republican “base” against leaders of their own party. By the time he had vanquished his rivals, not much of the GOP ideological structure was left.

Advertisement

Trump has filled the vacuum, but except for his fear-mongering and narcissism and cheerleading for torture, no one can say exactly with what. He pretends to be a cultural conservative, duly grumbling about abortion and bellowing for gun rights; but he’s an unconvincing homophobe and, as a proud philanderer and casino huckster, not exactly a “family values” kind of guy. To the extent that he has any coherent positions on economic and foreign policy, he is a protectionist, an anti-interventionist (except when he’s an interventionist), and a self-proclaimed master builder who swears he’ll fix America’s infrastructure ahead of schedule and under budget. “Believe me! I guarantee it!”

Despite his promise to slash taxes for the rich (one point on which his public statements and personal practice seem in accord), he was a registered Democrat for most of the first decade of this century, and traditional Republicans still suspect him of being a closet liberal. The Wall Street Journal reached recently into its lexicon of pejorative epithets to call him a “Big Spender.”

As for the Democrats, the rightward turn the party took twenty-five years ago under Bill Clinton—reduced financial regulation, weakened welfare support, expanded incarceration—appears to have run its course. For the first time since the 1960s, a vigorous left has emerged that cannot be dismissed as a protest from the fringe, and until Trump damaged himself with late-night tweets about a beauty contestant, followed by the release of the contemptible tape, there was fear that Hillary Clinton’s message of “I’m not Trump” might not be enough. As evidenced by Sanders’s remarkable run, the young want something more.

Suppose we do avert what Josh Marshall of Talking Points Memo plausibly calls “an extinction level event for our form of government”—namely, the election of Trump. The question remains whether the two parties can convert the shocks they have suffered into serious reflection about why a shameless demagogue hijacked one party and an obscure socialist mounted a serious challenge to the other. If so—it’s a long shot, I know—something good might yet come of these events.

Among Republicans, responsible conservatives are appalled by Trump’s vile brew of racism, misogyny, and xenophobia. They know they must not only purge the poison but find some way (this was supposed to be Jeb Bush’s or Marco Rubio’s assignment) to stop repelling minority and women voters. Presenting more problems for the future of the party, its blue-collar base may come to realize that the old “trickle-down” orthodoxy is a white-collar scam—a woefully inadequate response to the post-recession world in which they feel besieged and abandoned. Meanwhile, in the Democratic ranks there is a craving, especially among the young, for an activist government willing to make big investments in education and environmental protection, and to push for economic redistribution to a degree far beyond what the party has been able to deliver up to now.

In a cogent article published last spring in The New York Times, Steven Rattner offered a short explanation for how we got here: gridlock. He gives a dispiriting list of President Obama’s proposals that died in the frozen Congress: (1) an “infrastructure bank” to be funded by raising taxes on the rich; (2) wage insurance to help workers forced into lower-paying jobs by the contraction of domestic manufacturing; (3) enhanced child-care tax credits; (4) portable retirement plans.

These are sensible, if incremental, measures that Clinton as president would support and that could begin to alleviate, however slightly, the fears of the middle class. But even in the unlikely event that Democrats regain narrow majorities in Congress, her vaunted ability to “reach across the aisle” will do little good if there is no willing partner on the other side.

The lesson of this campaign, on both sides, is that with the fragile exception of the Affordable Care Act, which has expanded the number of citizens with health insurance, our clotted political system has failed to meet the emergency of rising inequality amid slow economic growth. (See Robert Gordon’s much-discussed book The Rise and Fall of American Growth, reviewed in these pages by William D. Nordhaus.) This reality—compounded by the effects of globalization in gutting the manufacturing sector and exporting low-skilled jobs—is what underlies the anger that Trump has stoked, that Sanders tried to turn to better purposes, and with which Clinton must contend as a candidate and, one hopes, as president.

If slow growth remains the norm, and the “pie” continues to shrink (relative to better times that older adults can remember), the first imperative of government will be to distribute the pieces more equitably with the very wealthy contributing a larger share. If that does not begin to happen, there will be an explosion that makes this year’s politics seem tame.

May Donald Trump be banished on November 8 to a new TV “reality” show with Roger Ailes as his co-star so they can hire and fire each other through eternity. But if the two political parties, unchastened, resume business as usual without a degree of the bipartisan spirit that our current president—who stands higher in the polls than either candidate—has called for since his first day in office, some version of the monster will be back.

Elizabeth Drew

Historians are going to have a hard time with this election. How to comprehend that someone manifestly unfit for the presidency won the nomination of one of the two major political parties and for some of the time was supported by almost as many of the voters as his opponent? How did the two major parties select the two most unpopular presidential nominees ever? To cite in explanation of the unqualified and even dangerous candidate’s success the “anger” of the white working class, much of it in areas hollowed out by departed manufacturing and by the closing of coal mines and other sources of energy deemed too “dirty,” is to miss other important sources of Donald Trump’s astonishing political success. It should not be entirely surprising that in our current culture a reality TV star is taken as a possible real president.

Trump’s candidacy has been made possible by a large portion of the electorate that swallowed his simplistic statements about the problems the country is facing and his impossible promises to solve them. For more than a year he has been telling huge audiences at rallies that he’d renegotiate trade deals and get better ones for America, as if he can unilaterally impose one-sided changes on trade agreements.

One can evoke with sympathy these voters’ lost sense that they live in a safe country with effective borders, or the fact that it’s their kids who fight and die in our dumb wars, but quite frankly, it’s the ignorance of much of the electorate that’s most troubling. Even though it’s not new, it’s more manifest this time because of Trump’s flaming unsuitedness for the office he’s seeking—at least he’s anxious not to be seen as a loser. It’s worth recalling that sixteen years ago we elected someone so ill-informed and mentally lazy that he got us into an unnecessary and disastrous war in the Middle East. Iraq is our Vietnam without the draft. Going back further, we should not forget that we elected a man whose troubled psyche was evident enough at the time and gave him rein until he nearly destroyed our constitutional system, and then faced impeachment and removal from office.

Some maintain that Trump wouldn’t have succeeded had he had only one or two opponents for his adopted party’s nomination, but that comforting thought is without much basis. During the nomination contest he said things that appealed to enough people’s economic frustrations and dark emotions, and each of his opponents had such weaknesses that if Trump had stood against any single one of them it’s not clear to me that he would have lost. The clapped-out Republican establishment, whose most notable policies were to cut taxes on the wealthy and promote trade agreements that coddle multinational corporations (not that some Democrats didn’t want to do the same), did not have much to offer the angry white working-class males who formed Trump’s base of support.

The first evidence of the Republican mainstream’s weakness came when Eric Cantor, the second-ranking Republican leader in Congress, was stunningly defeated for renomination in 2014. Cantor’s physical and personal remoteness was a factor—he preferred the company of expense-account lobbyists in Washington to that of his Virginia constituents. His defeat by a little-known economics professor backed by the Tea Party was a signal that was largely ignored by the rest of the party leadership. They told themselves that the decisive issue had not been the Republican establishment itself but immigration, and that Cantor had supported some free trade agreements; but this shaky interpretation of his defeat was largely imposed by the taken-by-surprise press.

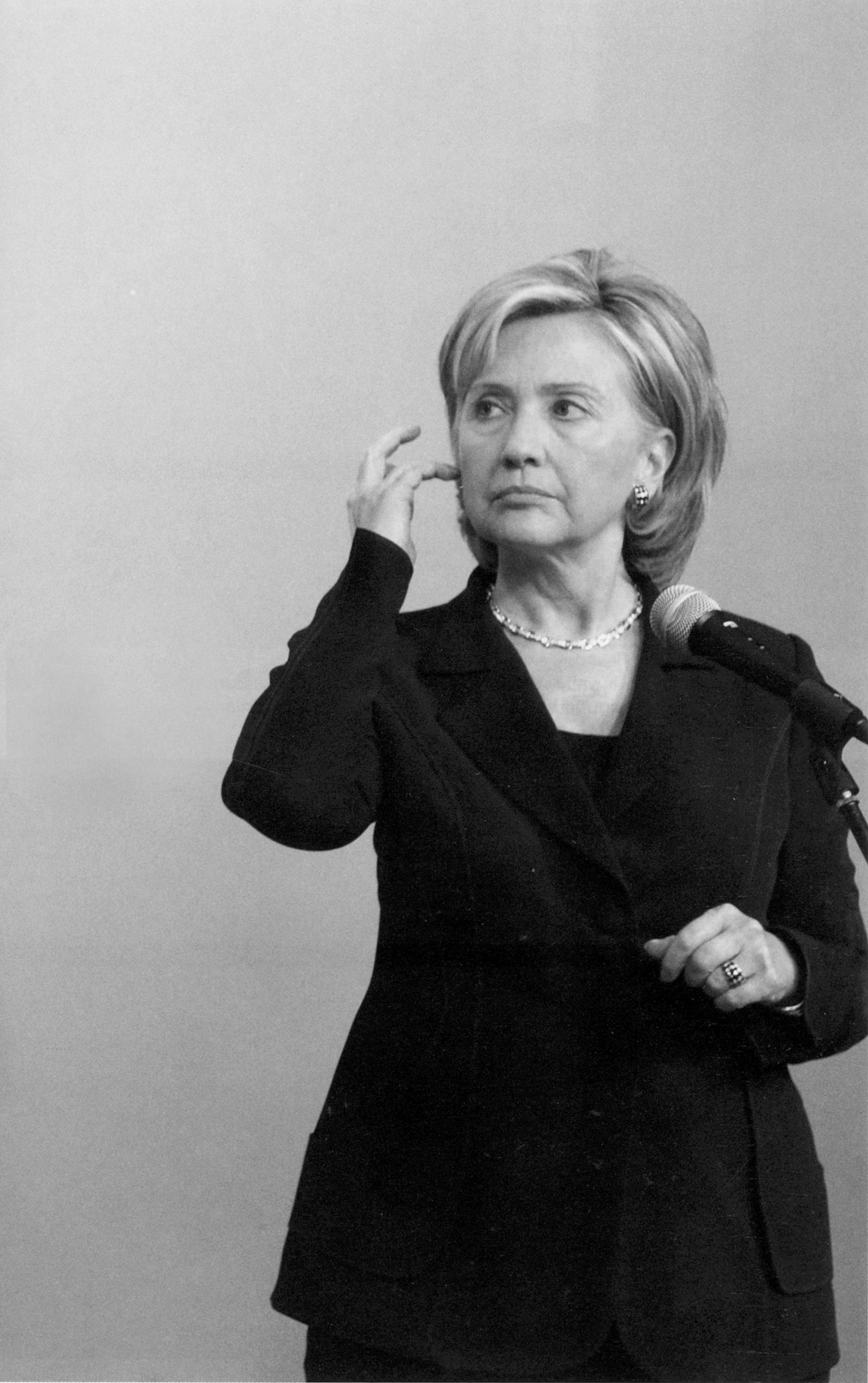

Hillary Clinton, too, reflects the inadequacy of her party. It lacked a bench of potentially strong candidates prepared to take Clinton on; for all the excitement he stirred, particularly among young people, Bernie Sanders was a fringe candidate. Her candidacy is based on an amalgam of programs without a vision; she has no overarching theme. Her two direct Democratic predecessors were cleverer and more skilled politicians.

My own view is that flawed though she is, Hillary Clinton is more unpopular than she deserves. Vile rumors spun by the fevered right have dogged her and her husband from the time they came to national prominence. Perhaps it was inevitable that Hillary Clinton would make a big mistake that would reflect her chronic passion for secrecy. Because she didn’t come clean, her mistake would become the “damn spot” of her campaign. We still have no idea what was in the some 33,000 e-mails that she destroyed; this allows Republicans to suggest nefarious possibilities. But while the server matter reflected some familiar traits, it isn’t everything about her.

Clinton commented recently that being a public figure is very difficult. But it’s the life she chose: and yet she’s been unable to reconcile a driving ambition with a strong penchant for privacy, the latter based on years of being investigated by congressional committees and a special prosecutor, usually on trumped-up charges, and of being the target of a right-wing vendetta.

No matter who wins, governing will be very difficult. The election won’t settle the deep disagreements between the two parties, and whatever happens to Trump, Trumpism isn’t likely to go away. Someone commented not long ago that we no longer know how to lose. The Republicans’ now-famous vow, even before Barack Obama was sworn in, to oppose everything he proposed to Congress was unprecedented in its implacability, but it could become the norm. If past pattern holds, Republican members of Congress will know that if they cooperate with a Democratic president they’ll be subject to punishment from the far right. It’s worth recalling that John Boehner was driven from the speakership by his own party because he dared to try to negotiate differences with Obama.

If Clinton wins, as now seems quite probable, she’s likely to face at least the same stiff opposition. She arouses a particularly strong venom in numerous Republicans, as well as the predictable animosity to a strong, smart woman. The congressional Republicans’ principal activity has been opposition. They have dedicated most of their legislative energy toward trying to kill Obamacare and defunding Planned Parenthood. Their recent obsessions have been to continue to investigate the FBI’s decision not to recommend prosecution of Clinton for her handling of classified material and whether she lied to Congress in response to questions about her server in the course of one of their seven investigations into Benghazi, all of which came up empty.

The possibility that Trump could win was over even before the release of the tape in which we hear him talking of assaulting women by grabbing them “by the pussy” and boast that his stardom then, in 2005, on the reality show The Apprentice, gave him leeway to do pretty much whatever he wanted sexually with women. By then, his standing in the polls had dropped to the point that he had no clear path to the necessary 270 electoral votes. The release of the tape, his schoolboy stunt before the October 9 debate of parading women who said they’d been sexually wronged by Bill Clinton, and even a debate performance less terrible than his first one led to an irretrievable slide that threatened to overwhelm the Republican congressional majorities. Thus Trump’s contributions to the election of 2016 have been to lower the bar on taste to the point that it seems impossible it can go any further and a civil war within the Republican Party.

We’re likely to live with the consequences of this election for a long time.

This Issue

November 10, 2016

Inside the Sacrifice Zone

Why Be a Parent?

Kierkegaard’s Rebellion

-

1

See my report, “The Magic of Donald Trump,” The New York Review, May 26, 2016. ↩

-

2

See Frank Rich, “Ronald Reagan Was Once Donald Trump,” New York, June 1, 2016. ↩