Jessica T. Mathews

Judging from the lack of attention to foreign policy in this campaign, one might conclude that few security challenges loom. Other than immigration policy (more a domestic than an international issue), trade, and, occasionally, the Iran nuclear deal, the rest of the world has been largely invisible.

Yet overwhelmingly, the Republican leaders most distraught by Donald Trump’s candidacy are foreign policy and international security experts. In March, 121 of them stated their “united…opposition” to someone “so utterly unfitted” to the job. A second group signed another such letter in August. Others, including former National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft, former Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, former Defense Secretary Robert Gates, and former chairwoman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, have independently announced their opposition. On a list compiled by The New York Times of the 110 most senior Republican leaders who have said they won’t vote for Trump, no fewer than seventy are foreign policy experts.

The reason for this unprecedented public opposition (notably not shared by economists and domestic policy experts) is that foreign policy practitioners believe the next president will confront perhaps the most dangerous international environment and the broadest and most intimidating set of challenges to US foreign policy since at least the end of the cold war, and arguably longer. Topping the list is a toxic relationship with Russia that neither side expects to improve anytime soon. Russian nationalism, stoked by wars in Crimea, eastern Ukraine, and Syria and by pervasive domestic propaganda, continues to strengthen. At the same time, Russians are experiencing the insecurity that comes with a shrinking economy caused by low oil prices and failed economic reform. Nationalism and insecurity are a dangerous mixture.

Putin is unlikely to purposefully start a war with NATO. But he is likely to challenge the US in ways that could easily escalate. Most dangerous are the Baltics: three tiny NATO-member states on Russia’s border, each with a sizable Russian-speaking population. A manufactured incident (such as Russia created in Ukraine) could provide the pretext Putin needs to take some military action, presenting the alliance, whose core commitment is that “an attack on one is an attack on all,” with a moment of truth.

Ukraine simmers. Any number of possible sequences of events could result in resumed warfare. And Russia will continue to deploy highly effective disinformation campaigns, intelligence operations, and cyberwar to weaken Europe and, in unprecedented attacks, the United States. Some of these things have been done before (including by the US), but today’s technology greatly enlarges their reach and impact.

Putin has ruled Russia for nearly twenty years. He is bold, shrewd, highly experienced, often reckless, and brilliant at playing a weak hand. He is also proud and thin-skinned. For whoever becomes president Putin will be a dangerous opponent.

He is not neutral in this campaign. Though Trump appears to be oblivious to the reason why, it should be no surprise that Putin is doing what he can to tilt the election toward a man he knows to be inexperienced, intemperate, ignorant of history and recent events, and therefore vulnerable to making terrible mistakes. The chance to help elect an American president who was unaware, until recently, that Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014 (“He’s not going into Ukraine, all right? You can mark it down”) and who dismisses the military alliance that is Russia’s principal nightmare (“Whether it [Ukraine] goes in [to NATO] or doesn’t go in, I wouldn’t care”) is not the kind of opportunity a man like Putin misses.

China also poses a risk of aggression fostered by nationalistic sentiment; in China’s case, too, it is compounded by the domestic tensions resulting from slowed economic growth. Beijing’s belligerence in its sweeping claims to nearly all of the South China Sea (against the claims of five other nations), and its construction of artificial islands and military facilities on them, confront Washington with a formidable problem.

The US must insist on the rule of law, support friends and allies in the region without forcing them to choose between the US and China, and make clear that it intends to remain a Pacific power, all without setting off open conflict or erasing the opportunity to work with Beijing where American and Chinese interests coincide. The two will also have to find some way to work together—and with South Korea and Japan—if the US does not want to live with an unstable regime in North Korea armed with nuclear weapons deliverable on long-range missiles. The pace of North Korea’s nuclear testing makes this an urgent task.

This is only the beginning. In the Middle East, a military victory over ISIS won’t mean very much unless stable governance to replace it can be devised in both Syria and Iraq. In Syria, that will require an enormous diplomatic effort to reach a deal that would satisfy in some degree the conflicting interests of Iran, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. It seems unlikely to be achievable without presidential commitment and a greater US willingness to give convincing military backing to its diplomacy. Otherwise, it seems that President Assad, with Russian support, is determined to kill or force out of the country every Syrian who opposes him.

Advertisement

At home, the new president will have to address the overblown antagonism toward trade agreements that has erupted in this campaign. She or he will have to distinguish between the inexorable effects of globalization that we cannot stop and those of negotiated trade deals we can control. Nationally, the economic and geopolitical benefits of trade agreements have far outweighed their costs, but millions of American workers have been selectively hurt by them, and redress is long overdue.

Trump has been right to point to the pain of these inequities but his solutions are utterly wrong. A policy of threats, international arm-twisting, and punitive tariffs will backfire. The Smoot-Hawley act of 1930—legislation that drastically raised US tariffs—showed how quickly tit-for-tat protectionism can become global economic catastrophe.

Rather, the answers lie at home, in a range of policies from tax reform to investment in infrastructure and R&D to education (including vocational education), as well as improved assistance programs for those who lose jobs: all of these responsive to irreversible changes in the global economy.

This daunting list touches only a few of the known challenges; among them should be near-term actions to mitigate the existential threat of long-term climate change. Moreover, unpleasant surprise is almost a certainty. Former British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had it right when he said that what he most feared was “events, dear boy, events.” Far more than most, today’s international landscape puts a premium on presidential experience, preparation, and a seasoned national security team.

On top of it all, the next president must address the national indecision over whether the United States wants to remain the major pillar of the international order, as it has been since 1945. Uncertainty about what the US is willing to do internationally is an intensifying cause of domestic polarization and foreign unease. Others are beginning to act based on assumptions about what the US might not do. There is no externally imposed deadline for addressing our ambivalence, but continuing to fail to do so carries a significant, and growing, cost.

Darryl Pinckney

Brexit unnerved a lot of people in the United States. Visitors from London warned that they had underestimated the resentment out there in left-behind England. We should heed the populist threat to take back sovereignty and identity, and we ought to remember that the popular will can be unpredictable, even destructive of the common good. Moreover, the racism in right-wing anti-immigrant politics in Europe was not much different from that in the air at Trump rallies.

However, even if every election is like a referendum in being a chance to express an opinion, the United States isn’t the European Union, an organization you can decide to leave. Most importantly, the racism driving the 2016 presidential campaign is very specifically an anti-Obama backlash: someone who doesn’t look like me is the most powerful man in the West and I’m still freaking out. That an obviously intellectual black man’s two-term presidency has been, on the whole, a success has put the right into a rage. He is their loss of power. They can’t get at President Obama anymore, but they can go all brimstone about Hillary Clinton.

At times the reporting on her health has felt like code for saying that as a woman of a certain age she is maybe not up to the job. Then, too, much anti-woman prejudice is disguised as I-just-don’t-like-Hillary. She first arrived in Washington those years ago, outsider and hick, having made clear during Bill’s campaign for the White House that as First Lady she would not bake cookies. Her power was to be upfront, not behind the scenes. She was that kind of woman, destined for pantsuits and forcing her way to the table. (People maybe also forget that for all his troubles with women, President Clinton respected them for their abilities, and hired them.) That Secretary Clinton and President Clinton are veteran politicians is a liability in the present political climate. They have too much to answer for.

Hillary Clinton has been attacked so many times that survival has made her overly cautious. You could wish for her to be brave, like Angela Merkel, who deserves the Nobel Peace Prize. But think of the hours Clinton has endured before congressional committees, getting grilled, being held to a higher standard, having to prove herself in interviews, while once again by comparison a white guy gets a free ride. Trump can say nearly anything, while her every remark—and what she doesn’t say—is subject to scrutiny. Articles that want to make him seem plausible are more alarming than his campaign. When a presidential candidate of a major American political party is openly admiring of the former head of the Soviet secret police as a national leader, it means that this view has an American constituency.

Advertisement

The Tea Party hijacked the Republican Party and then Trump stole it from them. For all the insurgency of his success in the primaries, he has had to resort in the general election campaign to the Republican Party strategy of the past forty-five years—carry the white South with either an overt or coded racist issue, such as “law enforcement” (formally known as “law and order,” which was revived by Trump during the first debate on September 26), health care entitlement, big government, birtherism, or immigration. Add to the list of traditional provocations the Second Amendment, the white person’s right to become an active shooter. However, the last two presidential contests have shown that, because of demographic change, even when it succeeds Nixon’s southern strategy isn’t enough anymore to give the Republican candidate victory in the Electoral College.

In a recent book, Our Compelling Interests: The Value of Diversity for Democracy and a Prosperous Society, edited by Earl Lewis and Nancy Cantor, the distinguished social analyst William H. Frey observes that in 2011 for the first time more nonwhite babies than white babies were born in the US. Frey talks of the globalized country that the US is becoming, and of the shift toward communities where there isn’t one majority group. Diversity is also an expression of generational difference. The white population is aging, while Hispanics, Frey observes, are younger than the population at large. They account for 16 percent of the US population, are mostly Mexican, and are concentrated primarily in California, Texas, and Florida.

The Republican Party blew it with the Hispanic vote over the immigration issue. Perhaps the Republicans have made into a bloc vote a population they had first courted as though it were not one. Senator Rubio’s old-fashioned immigrant’s narrative of hard work got upstaged by President Obama opening the door to Cuba. After that, no Republican seemed to know what to say to Hispanic-Americans that would not also offend the party’s mean white base.

Meanwhile, the perception of what is mainstream has begun to change. This election could very well demonstrate that our ideas of who constitutes the mainstream and what are majority opinions are already out of date. A lot of eligible voters are single mothers. In another essay in Our Compelling Interest, Thomas J. Sugrue, a historian of American politics, finds it paradoxical that diversity is widely accepted as a social aim at a time of profound income inequality. The lives of Americans have long been determined by racial or ethnic categories, and now America is becoming increasingly segregated by income.

Because conservative objections to universal suffrage have not changed since the first Constitutional Convention—the vote is a privilege, not a right—voting remains for many a radical act. The right tries hard to suppress the minority vote and redraw districts because Republicans know that nationally the demographics are not on their side and therefore control of Congress, governorships, and state legislatures is crucial to their power in the immediate future. One good reason that black people vote as a bloc is because of the historical importance of the courts in American history: some discriminatory voter ID laws got overturned this summer by appellate judges who were Democratic appointees (with one exception).

This election has many asking how much longer the American political process can go on as basically a two-party system. In The Great Suppression: Voting Rights, Corporate Cash, and the Conservative Assault on Democracy, MSNBC correspondent Zach Roth suggests that in 2016 money doesn’t necessarily buy the results it used to, that the brute force of Republican tactics faces a movement of the young to expand democracy. The Black Lives Matter manifesto talks of reparations, legislation, and self-determination, not of rebellion.

There is something of that worn-out feeling on the Democratic Party side as well. Maybe Hillary Clinton stands for the last of the baby boomer generation, those idealists from the 1960s who learned to compromise and then refused to get out of the way. They were going to be young forever and look at them now. Clinton will likely win—Nate Silver, hold my hand—but her election as the first woman president in American history does not feel like a moment of celebration, or a new beginning. Maybe the Clintons thought Obama could wait until after the second Clinton, but he had other ideas, and she now offers a caretaker administration until his successors sort themselves out.

Marilynne Robinson

Every four years Americans give themselves information about who they are and where they are on a spectrum of tradition and aspiration that normally frames our politics. The documents that have mattered to us have given us a set of ideals against which actual institutions and practices can be measured, and an abstract and deliberate language for encountering the issues that arise among people, which can, and often do, devolve into visceral and intractable conflict. The origins of these electoral arrangements are to be found in our history. They have been sustained over many generations by an agreed deference to custom and law.

This is to say that they are fragile, and that they are, in a sense, arbitrary. As resilient as they have proved to be through the trials of centuries, when their value and authority are not generally granted they can be overturned and dismissed, suddenly and almost casually. Let the idea take hold that elections are rigged, and popular government begins to seem no more than an illusionary empty exercise. Discredit the press, and the First Amendment is only a license to bloviate and slander. In other words, the viability of our system depends on a certain care, a restraint that avoids unjustified attacks and unfounded accusations against the system itself, and that demands integrity of those who hold positions of authority. If the generations that succeed us have a free press and elected governments, they will have the means to address our failures and their own.

We might well rob them of this birthright. Cynicism and opportunism are rampant at the moment, reinforcing each other and putting a degree of pressure on our institutions they have not felt since the years before the Civil War. They were breached then and disaster followed. Disaster in our time would no doubt be subtler, more insidious. The regional nature of the Civil War meant that the institutions of a large part of the country were not challenged and remained intact. The erosions we see now, epitomized in the appeal of Donald Trump, are at work everywhere, courtesy of the Internet, and of Rush Limbaugh, Fox News, and their ilk.

Strangely, for something that has almost the character of a movement, this change in our political culture is visionless, valueless, driven largely by an urge, signaled in taunts and slurs, sometimes realized in restrictive voting laws, to renege on advances we have made in the direction of racial and gender equality. It is true that these advances have been undercut by a neglect of the consequences for many Americans of globalization greatly compounded by policies of austerity and strategies of government paralysis that are the work of politicians who somehow manage to pass themselves off as populists.

Figures such as Newt Gingrich and Dennis Hastert devised means, notably party discipline and routine use or threat of the filibuster, to make the rules of governing obstruct governing. This is the sort of cleverness that discredits orderly process, just as the crowing of a billionaire over his lawful avoidance of taxes discredits the system of taxation. These obstructionists have provoked a frustration in much of the public that aligns with, and perversely affirms, the Reaganesque saw that government is the problem, not the solution.

So Donald Trump, outsider to the political system except in his admitted years of attempting to influence it with his money, is being looked to as an agent of change. His contempt for civilized norms of behavior apparently establishes him in the minds of many as a sort of chainsaw or wrecking ball, potential destroyer of rot and stagnation, though it is equally available to interpretation as the arrogance of a man who can and does sue or buy or finagle immunity from norms and laws, and who, in any case, clearly personifies the money grab that has brought such grief to the economically vulnerable.

We Americans are fond of describing ourselves as a rambunctious lot, history’s incorrigible children, for whom things come right in the end, at least often enough. But the fact is that “we,” the generations before us, have preserved and enhanced some precious ideas, with their attendant customs and traditions, through a tempestuous history—and a very long history, by the standards of societies that have attempted popular government. Restraint and decorum are not traits we look for in ourselves or our culture, and yet there is recently an unprecedented, often remarked, departure from civility and collegiality in our politics that has brought a precipitous decline in the functioning of our institutions. The state of our roads, bridges, and airports is not evidence of the decline of our civilization but the direct result of political calculation on the part of Mitch McConnell. Congress could make us first-world again whenever it chose to, reducing unemployment and stimulating the economy as it did so.

The absence of ordinary respect and truthfulness in Trump’s campaign invites comparison to the rise of foreign demagogues rather than American leaders. Trump takes every challenge as a vicious attack to be answered in kind times two, or ten. An appropriate response to Khizr Kahn’s question, posed at the Democratic Convention, “Have you even read the United States Constitution?” would be “Yes,” or, if honesty required, “It’s next on my list”—not a swipe at his wife.

Trump holds grudges against cabinet makers and beauty queens and the major press indiscriminately, a tendency in him that would be truly alarming if he actually held the reins of power. Why a man born to privilege should be continuously on the defensive, continuously ready to strike back without any reference to the appropriateness of the counterattack or to the grossly disproportionate force he can bring to bear on the perpetrator of some supposed slight, I do not know. An explanation might shed light on the gilded mop and the spray tan, and, perhaps, on the mores of the clans who control our economy.

In any case, Trump looms up before us, an outsized avatar of all that has gone wrong and might yet go wrong. We have to clean up our act. We have to stop tolerating lies and slander. We have to embrace again honesty and equity. We have to be careful to give responsibility every bit of respect it deserves. We cannot sustain our civilization on cynicism and resentment.

Garry Wills

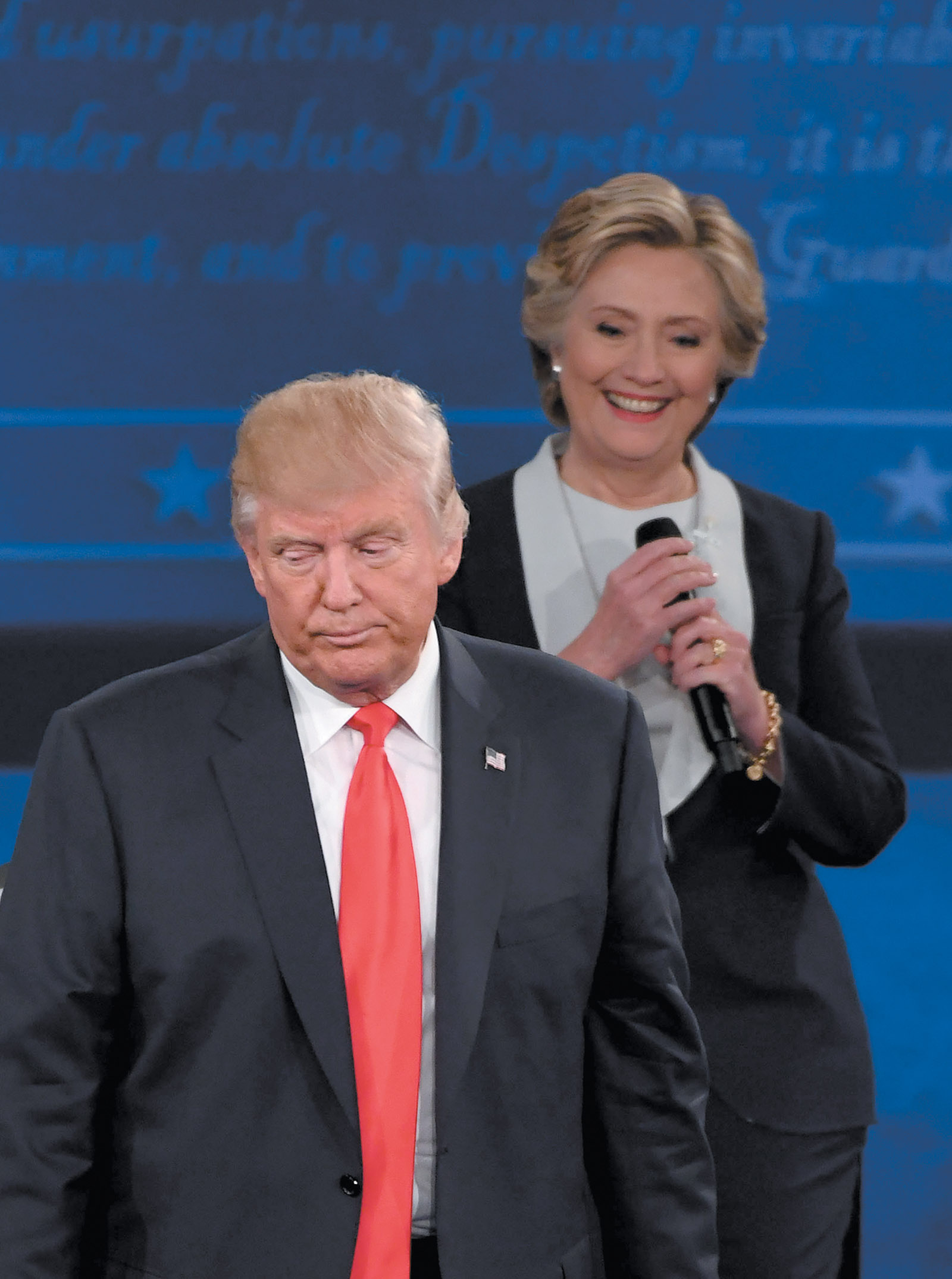

Donald Trump, in his second debate with Hillary Clinton, said in effect, “Make me president so I can throw our former secretary of state into prison.” Does he really think our presidents have the power to purge rivals as in a banana republic? In this weird campaign, it is hard to know what his words mean (if anything). Does anyone, for instance, take seriously his claim that Bill Ayers wrote President Obama’s book Dreams from My Father? How many believe (or care) that he saw thousands of New Jersey Muslims cheering the fall of the World Trade Center? How many really believe that he sent investigators to Hawaii who found out amazing things about Obama’s birth certificate? Or that the verifier of that birth certificate was killed to silence her? These claims are applauded as gestures without necessarily being taken “literally”—only the evil press does that.

How does one break through this jocular incontrovertibility?

One way to evaluate people, a way not often given enough importance, is by a human test of the company they keep—not just the people they meet by job or neighborhood, but ones they seek out or (more important) who seek them out. In his swinging days of the last century, Trump mixed as a celebrity with other celebrities. Some of these, like Roy Cohn, could also be useful to his business; others, like Bill and Hillary Clinton, could help him publicize one of his weddings. But what deeply intellectual or spiritual persons was he familiar with or respected by?

The circle of his trusted intimates is severely constricted—to those he can use or who want to use him. Otherwise he relies on his employees, his sons, and one of his daughters (who are also his employees), along with some of his wives (not all).

Crowds cheer him, but leading Republicans were openly contemptuous of him until he cowed them with fears of losing the Republican base (in every sense) of people angry at Muslims, Obama, and government. People like Chris (“no more Oreos”) Christie, or Ted (“Lyin’ Ted”) Cruz, or John (“not a war hero”) McCain did not so much join him as get run over by him. They are chained to his chariot wheels, prizes of war.

He does not have a circle of friends but an entourage. Where are the historians, philosophers, or poets he admires or who admire him? Whose are the minds that expand, challenge, or refresh his own? He reads nothing. The ghostwriter of his book The Art of the Deal, Tony Schwartz, spent eighteen months interviewing Trump and never saw a book on his desk, in his office, or in his apartment. (Trump thinks the Schwartz book is his own, like everything else in the room.) He knows and talks about little but his own excellence. He cannot learn from peers, since he thinks that he has none. Why consult others when they are, compared with him, losers?

Contrast this with Hillary Clinton’s intimates. I doubt that she has ever lost a friend, from school days on. Her staff has always been fiercely loyal, not out of compulsion but genuine admiration. She is respected by the numerous people she has worked with, for children’s rights, black rights, women’s rights—people like Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison. Among her friends are people of real achievement in various fields. I think of the civil rights historian Taylor Branch. He has been close to Bill and Hillary Clinton since 1972, when the three of them worked as a team for the George McGovern campaign in Texas. Before Hillary joined Bill there, when she was still working on the Nixon impeachment panel in Washington, Bill asked McGovern’s campaign manager, Gary Hart, if he could take a weekend off to go see his girlfriend in Washington. Hart said the McGovern campaign was too important for him to be thinking of girlfriends.

When Hillary Clinton told me that story in 1992, over lunch in Little Rock, she laughed, “Imagine that—from Gary Hart, of all people.” This was after Hart had his own girlfriend trouble with Donna Rice in 1987, and before Bill had his Monica Lewinsky trouble in 1998. I asked Branch, who met privately with the Clintons throughout their time in the White House, how and why Hillary put up with that betrayal. He said, “Because she’s crazy-in-love with him—always has been.” Somehow, the public image created of Hillary Clinton is not that of the intellectual, friend, and crazy-in-love person her many loyal and knowledgeable friends treasure.

I know this human test—who are the friends from whom one gets intellectual and emotional sustenance—is not the serious political analysis pundits are supposed to furrow their brows about. So instead of such touchy-feely stuff we get deep pronouncements of this sort: “Hillary Clinton is the end product of the System (whatever that is). Donald Trump is outside the System (whatever that means). The System has failed (at something, or everything). To escape the System, we must vote for Trump (or anyone) outside it. What do we have to lose?”

Everything, probably.

This Issue

November 10, 2016

Inside the Sacrifice Zone

Why Be a Parent?

Kierkegaard’s Rebellion