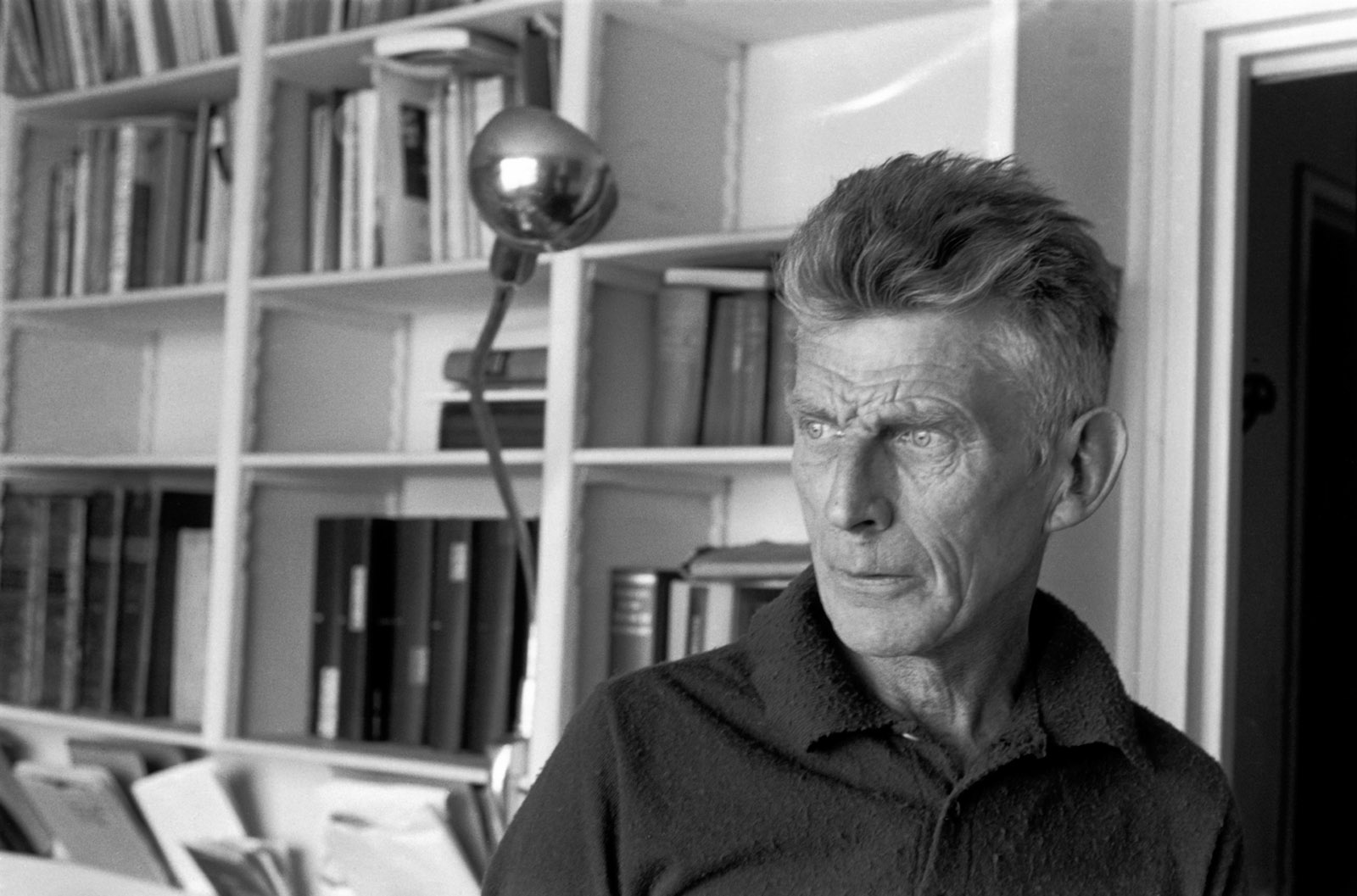

What did the elderly Samuel Beckett think about in the dark of night when he could not sleep? The hollowness of human existence? The inevitable failure of all expression? In fact, he played in his mind the first five holes of Carrickmines golf course overlooking Dublin Bay and facing the rugged hills he had walked so often with his father.

We know from the final volume of his marvelous letters that he played the course in reality for the last time on a visit to Dublin in 1966, when he was sixty. His sight was then badly affected by cataracts, lending a ghostly air to his golfing: “Could just see the ball on the tee, never in the air.” Over the following years, as more bodily woes afflict him, the idea of actually playing the Carrickmines course fades into impossibility: “Wd. love a few more swipes before the course is closed,” he writes to his nephew Edward in 1971, “but have no great hopes with my Dupuytren claws.” (Like the Protagonist in his late play Catastrophe, Beckett had Dupuytren’s syndrome, which locks the hands in a “clawlike” position.)

By 1975, as he is nearing seventy, the golf course is a place that can be seen only with the eyes of a former self: “I wouldn’t mind a few minutes in Ireland on the 4th (quondam 5th) tee, seeing the Welsh mountains with the then eyes. Then slice into the dimples.” (It is typical of the superb annotation throughout the four volumes of the letters that we know the dimples are a series of bumps and hollows to the right of the fourth fairway.) And by 1985, when eighty is looming, it has all become pure memory: “When I can’t sleep I play a round at Carrickmines but seldom get beyond the then short fifth.” His mind between waking and sleeping is drawn back to a well where errant golf balls found their nemesis: “From its shallows when short of balls as a boy I retrieved many a Warwick & even Spalding.”

Is all of this not a trivialization of a writer who, in these years, was battling heroically onward to wrest works of ferocious beauty from the depths of futility and despair? Do we really need to think of the creator of Not I or Ill Seen Ill Said, texts that still seem to occupy the outer reaches of expression in theater and in prose, as a golfer? And how does the publication of these letters meet the criterion laid down by Beckett himself when he gave permission in 1985 to Martha Fehsenfeld to edit his correspondence: “its reduction to those passages only having bearing on my work”? What bearing can the fourth hole at Carrickmines possibly have on late masterpieces like Ohio Impromptu or Company?

In truth, a very heavy bearing indeed. Firstly, these letters remind us that those works are not quite as strange as they seem—they are human after all, products of a mind that also contains memories of golf games, desires for Irish whiskey, “the heartache, and the thousand natural shocks/ That flesh is heir to.” Secondly, the changes in the way Beckett thinks of something as simple as a round of golf are not just poignant markers of the aging process. They really do bear on his work. A lived reality becomes a half-ghostly action, then a desire beyond reach, then something seen with “the then eyes” of a different self, and finally a well of memory from which things far more radiant than lost golf balls can be drawn.

The transformation of people and places into pure absences that are somehow more potent than any presence is the nub of Beckett’s late style. As he evokes the process with such mesmerizing economy in one of his last works, Worstward Ho, published in 1983 when he was seventy-seven: “The body again. Where none. The place again. Where none.” In the late Beckett, bodies are disappearing or immobilized; places are not inhabited but conjured in all their nonexistence by a great effort of will.

There is a deeply impressive painting in the National Gallery in London called An Old Man in an Armchair, made either by Rembrandt or by one of his followers. The light falls on the old man’s gnarled hand pressed onto his knotted, immensely weary brow. His eyes are cast downward and his face below them seems almost to be melting into his beard, as if his whole self is about to slide away into shadow. The eighty-one-year-old Beckett sent a postcard with an image of this painting to the writer Lawrence Shainberg in New York in 1987, telling him that he could not help with some unspecified problems but adding: “And perhaps one day like me [you] will cherish your ruins. And like me listen sadly to their silence.”

Advertisement

Ruins were Beckett’s natural habitat. The opening words of “Lessness,” his short story of 1969, are “Ruins true refuge long last.” Silence, however impossible for his voluble creatures, was always a consummation to be desired. Failing powers were for him the most potent kind, his aesthetic ideal being, as he put it in 1949 in his dialogues with Georges Duthuit:

The expression that there is nothing to express, nothing with which to express, nothing from which to express, no power to express, no desire to express, together with the obligation to express.

Death itself was with him from early on: birth, as the narrator in A Piece of Monologue has it, was the death of him. “Giacometti dead. George Devine dead,” he writes to Jacoba van Velde in January 1966, when he is not yet sixty. “Yes, drive me to Père Lachaise [cemetery] and go straight through the red lights.” Old age thus seems entirely becoming to him. He tells the stage and film designer Jocelyn Herbert about his cataract operations and adds, “Well there it is, old age in all its beauty, funny I didn’t see it sooner.” The joke, of course, is that he did see it sooner. He seldom saw anything else.

When in 1972 Beckett tells the Dublin publisher Liam Miller that he will discuss some proofs with him in person in Paris, he twists the expected phrase “viva voce” (by word of mouth) into “moribunda voce.” Beckett’s voices were always moribund. So, paradoxically, being actually moribund makes relatively little difference to his ability to carry on. Work is as laborious as a “small handsaw in knotty timber.” Writing the first sentence of an unspecified new work “feels like beginning Molloy only ¼ century worse.” When his poetic wings start to twitch they do so “like an old wasp’s in treacle.” Who else but Beckett could coin the phrase “work in regress”?

At times his imagination is nothing but a “gruesome dark.” And yet there is “no dope like it.” His “one ambition” is to “stupefy myself with useless words.” He is driven on by the approach of death: “When I start looking at walls I begin to see the writing. From which even my own is a relief.” So he keeps doing “that old crawl between the lines” even when he is distracted by “all this effing theatre,” the relentless demand for his presence at productions in Germany, France, and England. He can continue because he has long since become used to not being able to go on. As he puts it with such witty concision, “I’d give up if I hadn’t.”

And it is ultimately this later work, or at least the mental conditions in which it was created, that the letters illuminate, though they do so in indirect, subtle, and poignant ways. Letter-writing seems to have become if anything even more important to Beckett in his late years, even though his fame brought him the curse of missives such as the one he informs his friend and lover Barbara Bray of in 1967: “An appeal for help from a young English writer in Paris to Mr Bechet with quotation from Maloney Dies.”

It is easy to assume that Beckett would have been uncomfortable about much of what has now been published, but in fact he was deeply ambivalent about the revelation of his life. Amusingly, he confides to Barbara Bray in 1969 his fear of Richard Ellmann, the great biographer of the other Irish giants, Joyce, Yeats, and Wilde: “Keep off me, Dick, keep off me.” He rebuffs Mel Gussow’s interest in writing a biography: “My life was devoid of interest, to put it mildly.” He becomes increasingly indignant about Deirdre Bair’s unauthorized biography. And yet in Texts for Nothing, one of the voices he creates accuses his creator (implicitly Beckett) of lying when he claims that there is no connection between his own story and that of the character he imagines:

He tells his story every five minutes, saying it is not his, there’s cleverness for you…. He has me say things saying it’s not me, there’s profundity for you.

In the end—just months before his death—he succumbs to James Knowlson’s renewed entreaties: “To biography by you it’s Yes.”

Looking at the whole four volumes of this project, moreover, we can see how successful Beckett is in the battle to conceal so much of himself from posterity. There is not a single letter on his near-fatal involvement in the French Resistance, only the most glancing references to World War II and the Holocaust (the nearest he comes is a reply to a question about his novel Watt, written in hiding from the Gestapo: “All I can say to help you perhaps is that it was an escape operation from the horrors of that hateful time”), little on his crucial relationships with James Joyce and his daughter, Lucia, and virtually nothing on the woman with whom he shared almost half a century of his life, Suzanne Deschevaux-Dumesnil, whom he eventually married in 1961. Nor, after the very revealing letters to his closest friend Thomas McGreevy in the first volume, is there much in the way of deep introspection. “Don’t ask me,” he warns Bray in 1967, “to prise open my heart. Nasty black stuff would come out.”

Advertisement

His heart remains largely closed. Even as he plods through the miseries of old age, we have to remember that Beckett the letter-writer is an inveterate performer, making a show of those very miseries for his confidants. He is always at his funniest when the subject is either dreams of extinction or the general desolation of the world or his own bodily decay. Reading in Scientific American that the sun “will go phut in about 10 billion years,” he remarks that “we were born too soon.” Musing on the possibility of living in Portugal, he concedes, “It is true the summer must be hell. The spring too, and autumn.”

He is the great master of the comedy of false uplift. When a friend, Mary Hutchinson, dies he is delighted that she may have done so while watching his play on TV: “Peggy told me she lost consciousness while looking at Ghost Trio. Heartening thought.” He tells Ruby Cohn of his (in reality rather serious) illness in 1968: “This now appears to be a mere abscess of the lung. Judge of my gratification.” Getting about with his vision impaired by cataracts is “no drinking matter.” A skin eruption is reported to Bray: “Covered now with scabs merely which is a great improvement.” His painfully frozen shoulder leads him to boast: “You should see my breast stroke.” He contemplates a physical checkup: “A physical would finish me so perhaps time I had one.” The most hilarious moment is when he loses his dentures while swimming in the sea: “Makes speech & mastication [nigh] to impossible.” The next sentence is in itself a tiny Beckettian masterpiece of triumphant misery: “But drink and silence unimpaired.”

The tone here is familiar from Beckett’s prose and plays—he performs as one of his own characters. But does that mean that the letters tell us directly about his work? Not really—the illumination is, to fall into Beckettian paradoxical mode, decidedly shadowy.

One way to think about what the letters can and cannot tell us about Beckett’s creative process is to consider arguably the most important work of his late period, Not I, written in the spring of 1972. It is still, in performance, the most terrifying of theater experiences. In it, Beckett’s most extreme concentration of form—total darkness broken only by the light on a mouth hovering eight feet above the stage, emitting a ferocious babble at a pace too fast for conscious comprehension—puts an audience through something like torture. Sensory deprivation and aural distortion create a vertiginous disorientation that borders on the hallucinatory. Where can such a work possibly have come from?

On the surface, the letters seem to pluck out the heart of the mystery. To Bray in February 1972, just weeks before the composition of Not I, Beckett writes:

Vague image for a short play of a lit face (mouth) with ? to say and a cloaked hooded figure, sex unclear, completely still throughout, listening and watching. Latter suggested by an Arab woman all hidden in black absolutely motionless at the gate of a school in Taroudant and by the watching figures in the Caravaggio Malta decollation. Might produce 10 min. strangeness if text found.

Here we have, or appear to have, a creation tale in which we seem to trace the sources in ordinary experience of a most extraordinary work. It is from Caravaggio’s painting The Beheading of St. John the Baptist in a Maltese church and from an epiphany of a woman in Morocco that Not I springs. As Dan Gunn puts it in his otherwise excellent introduction to the volume, these two images coalesce “to form a key figure in the late-Beckett oeuvre.”

There’s one problem, though. The androgynous character in a djellaba who emerges from the conjunction of these source images is emphatically not a central figure in the late Beckett oeuvre. This is a false trail, a fascinating detective story that solves the wrong mystery. There is no doubt that these two moments of experience kick-started the process that led to Not I. But there is also no doubt that this is not what Not I ultimately became.

Beckett thought of a play in which there are two figures—the Mouth who speaks and suffers and the watching “Auditor” who is silent but who reacts to that suffering. He really liked the idea of the Auditor. But it didn’t function well in performance. Beckett worked closely with Anthony Page on the Royal Court production of Not I in 1973 (with the great Billie Whitelaw) and then directed the play himself at the Théâtre d’Orsay in 1976. He concluded, ruefully, that the Auditor just didn’t work. As he writes to the directors of a US production in 1986:

I should have written at once to advise you simply to omit the Auditor. He is very difficult to stage (light, position) and may well be of more harm than good. For me the play needs him but can do without him. I have never seen him function effectively.

So the “key” figure has turned out to be an aesthetic dud and the path back to the images that inspired it is a blind alley.

The real mystery of Not I lies in the text that in the letter to Bray is aptly delineated as “?” And the creation of that text turns out not to be a processing of recent experience but a strange influx of distant memory. There is no good reason for Mouth’s stream of language to be given a specific physical setting, but Beckett chooses to do so. The woman’s breakdown is happening, she tells us, in a place called Croker’s Acres. This place is real—it is a pasture close to his childhood home where Beckett often walked. And Mouth herself is an astonishing act of recall. Beckett told Knowlson:

I knew that woman in Ireland. I knew who she was—not “she” specifically, one single woman, but there were so many of those old crones, stumbling down the lanes, in the ditches, beside the hedgerows. Ireland is full of them. And I heard “her” saying what I wrote in Not I. I actually heard it.

Remarkably, Beckett, though increasingly removed from Ireland in reality—by 1968 he reckons his residence there to amount over the previous decade to an average of “about one hour a week”—was able in Not I to hear and give voice to a woman who has been repressed and silenced in that country’s terrible system of institutional control of unwanted women and children. He could do this not because he was making any kind of sociological study, but because the landscape of his childhood and youth was now haunting him. Just as he could see in his mind’s eye the fairways and greens of the Carrickmines golf course, he could hear the voices from the lanes and ditches nearby.

The letters don’t tell us exactly how these channels to the past are opened but they do give us a moving sense of how Beckett’s late work comes to be so ghostly. There is a particularly delightful card in the Little Museum of Dublin from Beckett in 1976 to a twelve-year-old boy, John Hughes, who was then living in Beckett’s old family home, Cooldrinagh, and who had written to ask, “I live in your house. Or rather, you used to live in my bedroom. Can you tell me a little about yourself?” Beckett patiently lists the schools he went to and the different bedrooms he had slept in in the house. It is the envoi that makes the card so affecting: “If you ever meet my ghost in house or grounds, give it my regards.”

The card is not included in this volume but the notion that the living, aging Beckett has a ghostly double still haunting the scenes of his youth runs through it, alongside the appearances of physical and imaginative apparitions. His final, beautiful prose text, Stirrings Still, begins with a self-haunting: “One night as he sat at his table head on hands he saw himself rise and go.” In the letters we find him trying out this line on his confidants, but with an even more explicitly spectral emphasis: “From where he sat with his head in his hands he saw himself rise and disappear.” He is thinking of himself as two selves—an increasingly immobile body and a spirit that is free to go.

Among the personal ghosts are specters from the 1930s, when the young Beckett was a moon in orbit around James Joyce. When Ezra Pound, then eighty-two, is in Paris in September 1968, and sends Beckett a note to say he has seen Endgame, Beckett remembers exactly where they first met, in a restaurant in the city, “and I can see the artichoke’s heart evading his fork while he enquired cuttingly what epic I was engaged on at the moment.” But there is no bitterness about this, or even about the rather larger matter of Pound’s fascism and Beckett’s antifascism. When they meet, they merely sit in silence for a while, but Beckett writes to Hugh Kenner that

I was so affected by his mien, face and silence that to my confusion ever since I embraced him on departure. I had at least that contact.

A simple and gentle letter to Lucia Joyce in St. Andrews hospital in Northampton in 1971 fills her in on family news, asks for her friend in the hospital “Miss Thursby,” and tells her that the Illustrated London News is changing to a monthly format: “[I] hope it continues to give you pleasure in this form.” It is obvious that Beckett has been paying for Lucia’s subscription. In this little act of continuing kindness Beckett retains a connection with a woman who once loved him and who became herself a kind of specter when she was overcome by mental illness in the late 1930s and removed from the daily world.

There is one ghost above all who hovers in the margins of these letters, sometimes manifesting itself on the page. Like a flashback from an old trauma, Beckett’s beloved father, William, who was just sixty-one when he died of a heart attack in June 1933, rises suddenly into consciousness. On June 26, 1975, while on a holiday in Tangier, he opens a letter to Bray: “This afternoon, 42 years ago, my father died. Why bring that up again?” When his cousin Sara dies in Dublin that August, Beckett is brought back again to his father’s death and something his uncle Gerald said to his mother, May: “I think of Gerald, June 1933, in the porch at Cooldrinagh, to the scent of verbena mother so loved, saying to her, Well, May, he’s got it over.”

There is a startling passage in a letter written to the poet Desmond Egan just over a year before Beckett’s death. Beckett speaks of his own approaching demise, using an image that he first deployed in the aftermath of his father’s death, that of the nymph Echo whose bones turn to stone: “The firm step is past & gone and Echo’s bones turned to stone.”* And then without obvious logic he adds, “unlike that loved face so far from that high board.” What does this mean? The first part means that he himself is dying, the second, that his father is still alive. It is the memory of his father urging him to dive into the sea in Dublin, already summoned by Beckett in the 1980 novella Company:

You stand at the tip of the high board. High above the sea. In it your father’s upturned face. Upturned to you. You look down to the loved trusted face. He calls to you to jump.

Beckett, in the letter, is reversing the natural order—he himself, still alive, is “past and gone.” His father, over half a century dead, is alive. Living, that is, in memory where the body’s cessation is of no account.

And it is the beauty of this full collection—surely one of the greatest editions of letters ever published—that this in turn takes us back to the first volume. Beckett wrote to Thomas McGreevy on August 2, 1933, from a “blank silent house,” giving him the news of his father’s death in tones that hint at his inexpressible trauma: “I can’t write about him, I can only walk the fields and climb the ditches after him.”

But now, at the end of his life, he can finally write about his father because experience has been transformed at last into a wraith, walking those same fields and hills. He and his father can walk together now because one of them, Beckett, is projecting himself back into the ghost of his childhood and the other is already a ghost. In Company, he is calculating as he walks the distances accumulated in all his hikes when he finds

Halted too at your elbow during these computations your father’s shade. In his old tramping rags. Finally on side by side from nought anew.

But to really follow the dead, he must become one of them. In Worstward Ho, written in 1982, he is himself a shade. He is a child and his father an old man and they walk the fields and mountains of south Dublin again:

Hand in hand with equal plod they go…. The child hand raised to reach the holding hand. Hold the old holding hand. Hold and be held. Plod on and never recede. Slowly with never a pause plod on and never recede…. Joined by held holding hands. Plod on as one. One shade. Another shade.

These letters, in the end, map a long tramp, not so much from life to death as from shade to shade. Beckett begins as an unformed consciousness, struggling to articulate itself, and he ends as a consciousness freed from its body and thus, ever alive.

-

*

See my review of Echo’s Bones in these pages, March 19, 2015. ↩