Lawrence Wright is one of the most lucid writers on the subject of Islamic extremism. His articles for The New Yorker have done a great deal to educate Americans who likely knew little about terrorism in the Middle East before September 11 and still are confused by it. His much-admired book The Looming Tower (2006) showed how al-Qaeda managed to carry out what is still the most audacious and powerful act of terrorism in history.

In his new book, The Terror Years, a collection of essays, Wright again helps us understand Islamic extremism and the West’s reaction to it. From al-Qaeda, formed in 1988, to the Taliban, which came into being in 1994, to the more recent Islamic State (IsiS), which announced its existence in 2013, and Boko Haram in Africa, Wright records the spread and evolution of the jihadist movement.

From the start, Wright plainly acknowledges America’s own contributions to the dire situation in the Middle East:

America’s involvement in the Middle East since 9/11 has been a long series of failures. Our own actions have been responsible for much of the unfolding catastrophe. The 2003 invasion of Iraq by US and coalition partners stands as one of the greatest blunders in American history.

Still, Wright maintains a studious balance in all his essays, attributing responsibility for the current situation both to unwise American decisions and to ambitions and disputes within the jihadist movement.

The first chapter, “The Man Behind bin Laden,” is a telling portrait of Ayman al-Zawahiri, the leader of the Egyptian Islamist terrorist group al-Jihad, who wrote, together with Osama bin Laden, the fatwa that in 1998 officially announced the formation of the International Islamic Front for Jihad on the Jews and Crusaders, an alliance of international jihadist groups, and that called on Muslims to kill Americans and their allies anywhere in the world. In June 2001, the two men formally merged al-Qaeda and al-Jihad, with bin Laden serving as the new organization’s public face, and Zawahiri doing much of the plotting and decision-making; he planned, for instance, the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Wright describes Zawahiri’s upper-middle-class professional background in Cairo, his career as a surgeon for the Egyptian army, his bitter years in prison, and his eventual rise to al-Jihad’s leadership. In the years since the essay’s original publication, bin Laden has been killed and Zawahiri has been recognized as the head of al-Qaeda. Although his movements are secret, he remains in charge today.

Describing video footage from the opening day of Zawahiri’s 1982 trial for conspiring in the killing of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, Wright recalls one of the most important moments in the history of Islamic extremism:

Finally, the camera settles on Zawahiri, who stands apart from the chaos with a look of solemn, focused intensity…. At a signal, the other prisoners fall silent, and Zawahiri cries out, “…Who are we? Who are we?… We are Muslims who believe in their religion, both in ideology and practice, and hence we tried our best to establish an Islamic state and an Islamic society!”

This is virtually the same proclamation of belief that is made by ISIS suicide bombers when they yell “Allah o Akbar” just before setting off their deadly bombs. In the video, Zawahiri goes on to describe how the Egyptian jailers tortured him and his fellow inmates: “They kicked us, they beat us, they whipped us with electric cables, they shocked us with electricity!” When Zawahiri was released from jail in 1984, he “emerged,” according to Wright, “a hardened radical whose beliefs had been hammered into brilliant resolve.” We are reminded here of the Guantánamo inmates who likewise got both real and imagined scars in prison, and who, when freed, returned to jihadist organizations in order to take revenge on their jailers. (According to a recent intelligence report cited by The New York Times, 122 of the 693 detainees transferred out of Guantánamo—more than 17 percent—“reengage[d] in terrorist or insurgent activities after they were transferred.”)

Zawahiri sought to introduce sharia law, the traditional religious law of Islam, in the Arab world, to restore the power of the early Muslim caliphate, and to carry out a revolution—ambitions that bring his doctrinal beliefs close to those of ISIS. Bin Laden, on the other hand, sought first to attack the US and other distant Western powers that sustained Arab autocracies—goals that prefigure the present aims of al-Qaeda. Wright ties his discussion of this doctrinal conflict to the personalities of the men who defended them. For him Zawahiri is a “pious, determined, and embittered” revolutionary who had developed a “hunger…for leadership,” and bin Laden an “idealist given to causes [who] sought direction.”

Throughout the book, Wright describes more clearly than most writers on terrorism the attitudes, clothes, and habits of the characters he discusses. These descriptions are particularly impressive since he has not seen many of the terrorists in person. Here, for instance, is Wright on Zawahiri as a young man:

Advertisement

Zawahiri was tall and slender, and he wore a mustache that paralleled the flat lines of his mouth. His face was thin, and his hairline was in retreat. He dressed in Western clothes, usually a coat and tie.

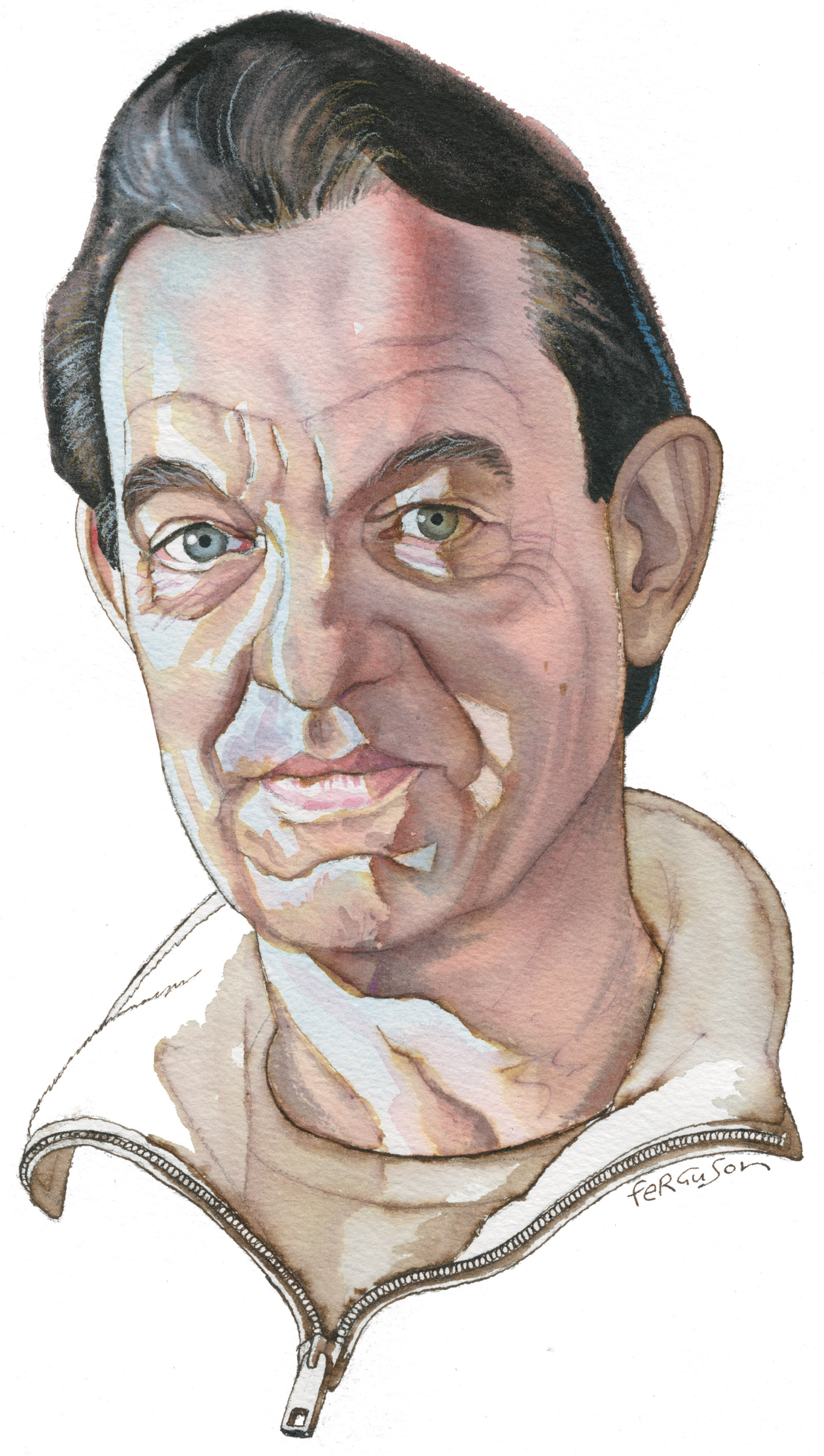

Wright also has much to say about John P. O’Neill, the legendary FBI officer who tried to chase down al-Qaeda during the 1990s when hardly anyone else in the FBI was taking its threat seriously. O’Neill died on September 11 in the World Trade Center, where he served as head of security. He was coordinating evacuation efforts on one of the top floors as the south tower collapsed:

He had something of the old-time G-man about him. He wore a thick pinky ring and carried a nine-millimeter automatic strapped to his ankle. He talked tough, in a New Jersey accent that many loved to imitate. He was darkly handsome, with winking black eyes and slicked-back hair. He favored fine cigars and Chivas Regal and water with a twist.

Wright also does not fail to mention that O’Neill, at the time of his death, was involved with three girlfriends who did not know about one another.

Wright pays the same kind of attention to detail when he describes the nature of terrorism before and after September 11. Writing about Gaza in 2009 he gives a detailed account of how the territory, formerly under Egyptian rule, was occupied and blockaded by the Israelis. He describes sparse zoos with donkeys painted to look like zebras, shuttered shops, machine-gun emplacements along the buffer zone on the Israeli border, and “a fourteen-year-old boy with shards of glass blown into his back and leg” being carried out of a school hit by an Israeli rocket intended for Hamas. In another chapter, Wright portrays the chaos and repression within the Syrian film industry as a microcosm of the forces—for and against Assad—that were destroying the country. He deals with the US not mainly by discussion of official policy, but by his accounts of O’Neill and his protégé, Ali Soufan, and the head of the National Security Agency, John Michael McConnell.

In 2003, having failed to obtain a visa to Saudi Arabia as a journalist, Wright found a job training young Saudi reporters in Jeddah. He describes his first meeting with the three female journalists he would be overseeing, “all in black abayas and hijabs,” one of them with “only a pair of cat-eye glasses peeking out from the mask of black cloth.” Wright proposed to the young journalists that they write about the fire that had broken out in 2002 in the Thirty-first Girls’ Middle School in Mecca, during which fifteen students were trampled to death and over fifty were injured. He asked them to find out whether any changes had been made, for either the better or the worse, since the fire. They might, he said, talk to the victims’ families, civil defense authorities, and women educators. While one of the young journalists expressed interest in the project, the woman whose entire body was covered, up to her glasses, simply laughed and warned Wright, “that’s not the way things work here,” referring to the Ministry of the Interior’s strict censorship of the Saudi press.

Wright ends his book with the story of the four American journalists and aid workers who were beheaded by ISIS in 2014. He describes the US government’s inadequate response to their capture, and the heroism of David Bradley, the wealthy owner of The Atlantic, who attempted to rescue them. Bradley’s fierce commitment to his staff is perhaps unprecedented in the history of media magnates.

Wright says little in his essays about the Taliban in Afghanistan and the significance of the shelter and training facilities they offered bin Laden, without which it is doubtful that the September 11 attack could have been carried out. After conducting a fifteen-year war against the Taliban—the longest-running war in American history—the US has still failed to eliminate it or to rebuild most of what has been destroyed in Afghanistan. Much of this failure is owing not to the strength of the Taliban, but to the US’s decision to attack Iraq and its neglect of developments in Afghanistan. As Wright recently told an interviewer:

Going into Iraq was a huge failure because we were in Afghanistan. We had al-Qaeda on the run…. The whole world had turned against al-Qaeda at that point, and the Taliban was totally demoralized, and we had bin Laden on the run. We might have gotten him, and all those Special Forces, all those people on the ground were diverted to Iraq and left with a residual force, they really couldn’t handle what was going on. They thought it was done…. And so cracking open Iraq was, you know, the main sin that we created in the Middle East in modern times.

So far, Wright has not written extensively about Pakistan, which backed the Afghan Mujahideen in the 1980s against the Soviet Union and the Taliban in the 1990s; and he says little, too, about Pakistan’s own Islamic extremists. In the 1990s, the Pakistani government gave strong support to several Pakistani groups from the Punjab that were trained to fight the Indian army in Indian Kashmir. Later local extremist Sunni groups proliferated in Pakistan, targeting Shias and other minorities, while Pakistani government agencies continued to give backing to the Taliban, even after September 11. Pakistan’s policy of apparently approving Washington’s failed strategies in Afghanistan while also covertly supporting the Taliban has done much to ensure the US government’s failure in Afghanistan.

Advertisement

Since bin Laden was discovered and killed in Pakistan in 2011, however, the Taliban leaders continue to live there. Mullah Mansour, who became the Taliban leader in July 2015, was killed in a US drone attack inside Pakistan in May of this year. Today al-Qaeda in South Asia is largely made up of Pakistani extremists who protect Zawahiri as he hides out on the Pakistan–Afghanistan border. During the past two years the Pakistani army has driven out many terrorist groups who have targeted local populations, but it has not attempted to suppress the Punjabi groups fighting India or the Afghan leadership of the Taliban. Pakistan’s lame explanation for continuing to tolerate such terrorist groups is that they defend Pakistan against Indian aggression and excessive Indian influence in Afghanistan. This is just the kind of evasive policy Wright might have discussed.

Like most Americans interested in the Middle East, moreover, Wright says little about the large-scale American demonstrations against the Iraq war that helped to encourage support for Barack Obama, who had spoken out in 2002 against America’s involvement in “dumb wars.” The links between those demonstrations and the subsequent emergence of the “Occupy” movements in American cities and, to some degree, the movement of Bernie Sanders have not had the attention they deserve.

Still, Wright’s book is essentially a collection of articles that does not claim to be comprehensive and such omissions are to be expected in his superb and gracefully written accounts of the past three decades. Although his stories take place in settings of war, terror, and death, each of them is built around a few particular individuals, many of whom have bravely confronted the reality of terrorism, and some who have acted heroically. These heroes are often ordinary people who quietly resist and refuse to surrender to the forces that threaten to destroy them. In a few lines Wright portrays the resilience of one such person, a severely wounded survivor of the al-Qaeda bombing of the naval destroyer the USS Cole, which was badly damaged by a Taliban attack in Yemen in 2000:

Three of the sailors were too badly wounded to be interviewed, and yet one of them, Petty Officer Kathy Lopez, who was completely swathed in bandages, insistently motioned that she wanted to say something. A nurse put her ear to the sailor’s lips to hear the whispered words. She said, “Get them.”

Wright is particularly insightful and sympathetic in his account of John P. O’Neill’s youthful and energetic sidekick, FBI Special Agent Ali Soufan, a Lebanese-American, a Muslim, and in 2000 the only FBI agent in New York who spoke Arabic. Soufan, like O’Neill, recognized the danger of al-Qaeda well before September 11. When the USS Cole was bombed and most Washington experts doubted that al-Qaeda was sophisticated or audacious enough to attack a US warship, O’Neill put Soufan, then twenty-nine, in charge of the investigation.

When Soufan discovered that the CIA knew that two of the al-Qaeda hijackers had entered the US well before September 11 but did not inform the FBI about them, “he ran into the bathroom and threw up.” After resigning from the FBI in 2005 he established the Soufan Group in Association with the Center on National Security at Fordham University, a private international security and intelligence organization—one of the best, according to Western officials I have spoken to. He is still frequently consulted by the US government, and his company’s daily terrorism brief is seen as required reading for anyone concerned with the subject.

Wright is fascinated by factional disputes within al-Qaeda, and by the openly critical views of Osama bin Laden held by some of its members, who are often little known. He devotes an entire chapter to Dr. Fadl—Sayyid Imam al-Sharif—a well-known extremist and former leader of the Egyptian group al-Jihad who, in 2008, denounced the use of random violence from his jail cell in Cairo. Dozens of other jailed militants quickly joined with him. Zawahiri responded with anger and venom. “Do they now have fax machines in Egyptian jail cells?” he asked sarcastically in a letter to his former comrades.

Wright traces the origins of this ideological dispute within al-Qaeda, concerning the necessity of violence, back to 1968, when Fadl and Zawahiri met at Cairo University’s medical school. While the two men shared many Salafist views at the time of their first meeting, they gradually grew apart. Zawahiri’s experience in prison hardened his “appetite for revenge”; Fadl dedicated himself to working as a surgeon for injured combatants and became a spiritual guide to the jihadists. In 1994, when Fadl gave Zawahiri a copy of the manuscript he had been working on for years—The Compendium of the Pursuit of Divine Knowledge—Zawahiri significantly changed the text, removing Fadl’s critiques of the jihadist movement. He published the revised version under the name Guide to the Path of Righteousness for Jihad and Belief without Fadl’s knowledge or permission.

It was against this background that Fadl announced in 2008 that he was launching from prison a campaign based on principles of nonviolence, which were scornfully rejected by Zawahiri. Wright explains both the personal and the doctrinal aspects of the animosity between the two men with the same fairness and objectivity he brings to his Western subjects. His writing is devoid of the cynicism or indignation that often characterizes writing about terrorism. Fadl was released from prison in 2011, several years after Wright had written about him; perhaps more will be said about him in a subsequent book.

Another rebel within al-Qaeda of interest to Wright (and few others) is Abu Musab al-Suri (originally Mustafa Setmariam Nasar), who remains at large. Born in Syria, al-Suri observed the repression of the Muslim Brotherhood by President Hafez al-Assad in the 1980s. He fled in 1985 to Spain where he got married and became a Spanish citizen before leaving for Afghanistan in 1987 to join al-Qaeda. In 1999, al-Suri criticized bin Laden by e-mail for attacking American targets and forcing the US to respond militarily, which he saw as a fundamental error. He also accused bin Laden and the other al-Qaeda leaders of not sufficiently respecting their Taliban hosts.

In 2004, while hiding out in Iran, he published on the Internet what became a well-known jihadist polemic, Call for Worldwide Islamic Resistance, in which he predicted the failures both of al-Qaeda and of the current jihadist movement. He proposed major changes in jihadist strategy, writing, for instance: “Without confrontation in the field and seizing control of the land, we cannot establish a state, which is the strategic goal of the resistance.” ISIS has now taken up this goal, although it has been driven from control in several cities in Iraq and faces an attack on Mosul. There is no evidence that al-Suri has given it any support.

Wright also describes vividly the brutality of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the Jordanian who led the al-Qaeda resistance to the Americans in Iraq and promoted the mass slaughter of Shia Muslims. After he was killed by an American air attack in 2006, the terror organization he had developed eventually became ISIS, which has become more extreme in its beliefs than Zarqawi himself.

Wright’s essays on Saudi Arabia and Syria help us understand the chaos that has engulfed Syria and Iraq and that may eventually extend to Saudi Arabia as well. They provide no solutions to the intractable questions that they ask. Why are a fraction of the world’s one billion Muslims killing others and getting killed in a nihilistic cause that values death above life? How could a profoundly negative reinterpretation of Islam by a small group of jihadists as such a controversial and violent sect have emerged, over a relatively few years? Why have so many nations, particularly in Europe and North America, refused to recognize and help relieve the suffering of millions of Arab refugees?

Wright does not claim to have answers, only to provide insights into some of the sources of the tragedy. It is, he writes,

common to suggest that dealing with root causes of terrorism is the best and maybe the only way to bring it to an end, but there is very little evidence to support that notion. Poverty doesn’t necessarily lead to acts of terror. Nor does tyranny, nor do wars, corruption, a lack of education or opportunity, physical abuse…. Not one of these factors by itself is sufficient to say that here at last is the reason that idealistic young people line up for the opportunity to behead their opponents or blow themselves up in a fruit market. But each of them is a tributary in a mighty river that floods the Middle East, a river that we can call Despair.