Nobody can know another’s marriage from the inside. Even with people we know well, the relationship we see is merely the deceptive outward show, the public illusion; at home the marriage shifts into some other mode entirely, with intimate deployments of coldness or affection, manipulation or control, altering the balance at every moment. No outsider can tell with any certainty what is really going on.

Faced with this reality, Elaine Showalter has bravely taken on the task of examining the inner workings of a marriage that ended nearly a century and a half ago. That she succeeds as well as she does is a tribute not only to her scholarly diligence, but also to her proven historical curiosity and her fluent prose.

Even during the Victorian period, an era noteworthy for its odd marriages, the partnership of Julia Ward Howe and Samuel Gridley Howe was viewed as unusual. There was, to begin with, the celebrity of both parties. They did not become famous at the same time or in the same fields but they achieved great renown nonetheless. And in part because the public eye was already upon them, the cracks in their marriage became known even during their lifetimes. That Julia Ward Howe was the author of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and a noted activist on behalf of women’s rights only gave further fuel to the idea of a vocal if not strident woman whose life had been inhibited by a demanding and repressive husband. These rumors of marital strain were fed rather than quashed by Julia’s own publications, and they were further publicized after her death by the accounts of their surviving children, three out of four of whom became writers.

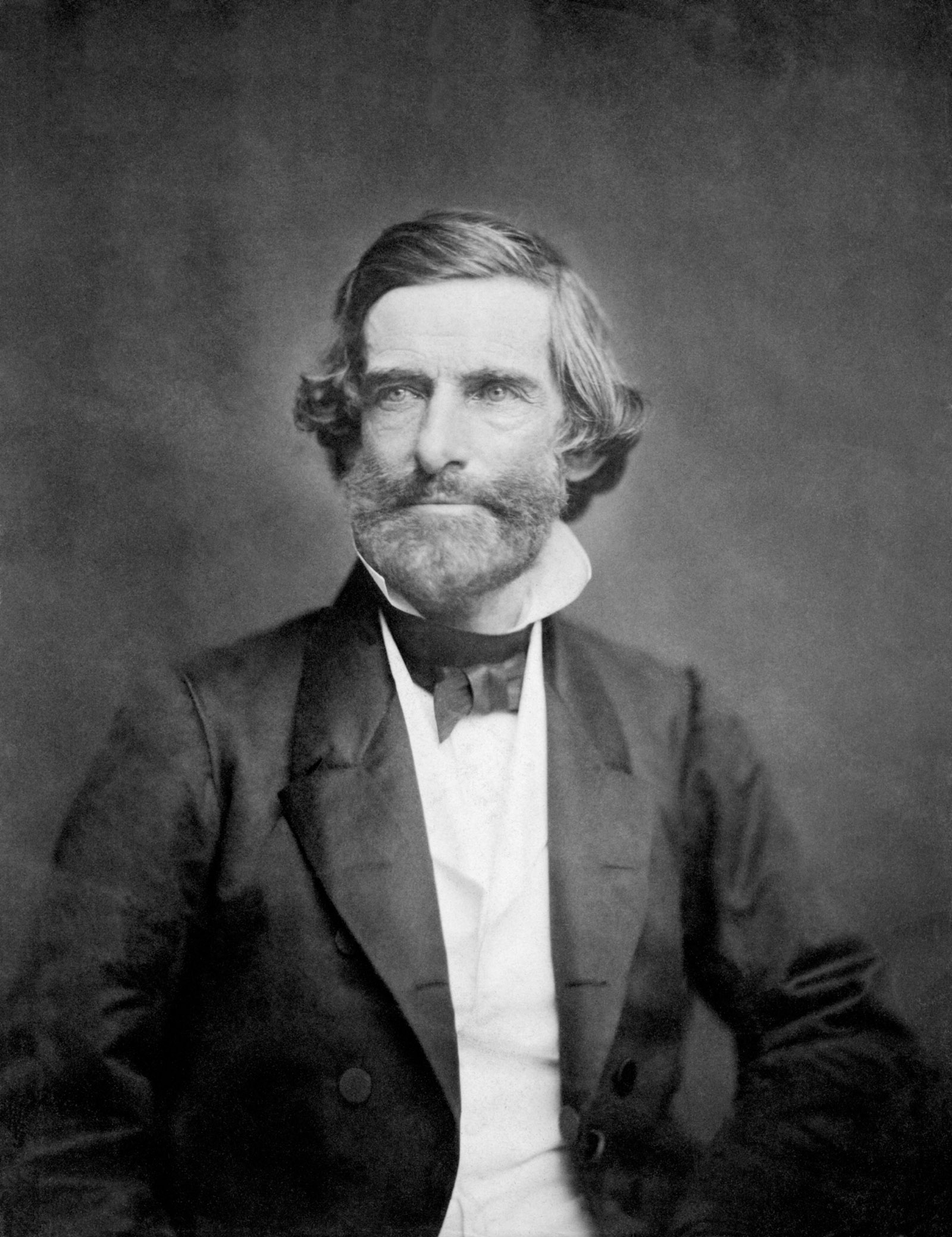

When they married in 1843, it was Samuel who was by far the more famous. As a doctor just out of Harvard Medical School, he’d joined the Greek War of Independence in 1824, the same year Byron died in that conflict. Howe stayed in Greece for six years, fighting and supplying medical help, for which service he was eventually named a Chevalier of the Order of St. Saviour—a title that gave rise to his lifelong nickname, Chev. Upon his return to Boston, he was appointed head of the new Perkins School for the Blind, an institution he made famous by promoting the accomplishments of a deaf-blind girl named Laura Bridgman. (Chev’s and Laura’s much-chronicled achievements as teacher and student were eclipsed only when a subsequent pair from the Perkins School, Annie Sullivan and Helen Keller, became even greater celebrities after Chev’s death.) By the time the New York heiress Julia Ward first met Chev Howe, on an 1841 visit to Boston, two years after her father died, he was already a well-known figure in the philanthropic and literary circles of both England and New England. He was also, with his dark hair and beard, sculpted cheekbones, piercing blue eyes, and “manly” carriage, extraordinarily handsome—a quality he was to retain well into old age.

Julia, at twenty-two, had her admirers as well. One of three rich and adored sisters known as the Three Graces of Bond Street, she stood out for her red hair, her delicate complexion, her small size (she was just over five feet), and her excellent singing. Probably it was her well-trained voice that led her to be called the Diva by her New York acquaintances, though it could also have been her manner: from a very early age, Julia Ward had been sure of her own importance and had demanded attention accordingly. Although during his lifetime her restrictive father, an extremely rich banker, had allowed her only a limited formal education, she and her various tutors had made sure she acquired French, Italian, and German as well as wide-ranging musical and literary knowledge. By the time she met Chev, she had written a number of poems (none as yet published in book form, though not for want of trying) and had published precocious essays on Lamartine, Goethe, and Schiller in the Literary and Theological Review.

Though her talents may have helped draw Samuel Howe to her, they were not what made him want to marry her. “That she is a pure, & noble, & gifted creature, we all knew…—but oh! how little compared to what I alone have found her—gushing over with tenderness & love,” the forty-two-year- old Howe wrote to his close friend Longfellow about his twenty-four-year-old fiancée. He wanted a helpmeet—a woman who would be happy as the wife of an active, effective man, not to mention the mother of the many children he longed for—and Julia, at least for a time, believed herself capable of that. “The Chevalier’s way will be a very charming way, and is, henceforth, to be mine,” she noted confidently at the time of her engagement.

Advertisement

Because of Julia’s immense wealth, her brother Sam and her uncle John required Chev to sign an “antenuptial agreement,” whereby much of his bride’s inheritance would remain under the control of her male relatives. She also, unusually for the time, insisted on retaining her maiden name as part of her name, so that she became Mrs. Julia Ward Howe rather than Mrs. Samuel Gridley Howe. Chev did not object. They were in love, they were both extremely confident people, and they foresaw no problems, despite the fact that the Ward brothers secretly viewed Chev as a “confounded bit of Boston granite,” while Longfellow privately worried that Julia was a “damsel of force and beauty…carrying almost too many guns for any man who does not want to be firing salutes all the time.”

It would be easy to view Samuel Howe as the villain of the drama that followed: the assertive, single-minded, somewhat self-centered husband who forbade his intelligent wife to write poetry or give suffragist speeches, confined her to the house with six children (one of whom died in early childhood, another as a young adult), and vociferously deplored her every move toward independence. When you first start reading Elaine Showalter’s account, you may think she takes such a view. But in fact her book is one of the more balanced portrayals of this strained, strenuous relationship. Though she most often sides with Julia, the author of The Civil Wars of Julia Ward Howe also allows us to see why Samuel might have found his wife impossible. Compared to the adulatory biographies that preceded hers, Showalter’s is in many ways a model of fairness.

The couple’s three surviving daughters, who first published a joint biography of Julia in 1916 (six years after her death), were anxious to cement their mother’s reputation as an American heroine even as they resuscitated their long-dead father, who had been left in the shadows by his more famous spouse. The biographies since then take for granted that Julia is the subject of our interest, and repeatedly show Chev as the force that had to be overcome for her to achieve her destiny. Showalter’s claim that no previous biography “sees the marriage of the Howes as a paradigmatic clash of nineteenth-century male and female ambitions” is not really true; they almost all do, as is made clear in titles like Valarie Ziegler’s Diva Julia: The Public Romance and the Private Agony (2003). Showalter has drawn heavily on this and many other sources for her own book, but she has also gone beyond them, recognizing, as Phyllis Rose did decades earlier, that every marriage is “two narrative constructs…two versions of reality.” By quoting those words from Rose’s Parallel Lives in the midst of her own book, Showalter plants herself in a tradition that is generously and comprehensively, as opposed to crudely and narrowly, feminist.

As Showalter presents it, the first signs of tension between Chev and Julia emerged on their sixteen-month wedding trip to Europe. Samuel Gridley Howe’s standing as a “London lion”—a reputation earned during his Greek period and burnished by his Perkins achievements—clearly got on his bride’s nerves. Well-dressed women flocked to his side at parties, and literary lights such as Thomas Carlyle and Maria Edgeworth would invite the couple to lunch, only to focus on the husband and completely ignore the wife.

By the time they paid a visit to William Wordsworth in the Lake Country, Julia had become unable to restrain herself. “Why did you not keep your money at home?” she burst out, when the elderly poet and his widowed daughter complained about losing money on American investments. “The Husband is an intelligent man,” Wordsworth wrote after their departure, “and his Wife passes among Americans as a great specimen of the best they produce in female character.” His daughter’s verdict was harsher and more direct: “A horrid, rude, clever, radical woman.”

But Julia’s worst behavior was saved for the end of their travels, when the Howes returned from Italy to England in order to catch their ship home. Pursuing his relentless research into every kind of handicapped education—a preoccupation that had marked the entire trip, including the period in Rome when Julia was giving birth to their first child—Chev dashed down to Portsmouth just before their departure in order to meet with an old woman who was not only blind and deaf, but also suffered from other noticeable disabilities. Upon his return, Julia presented him with a poetic report on his trip, couched in the rhythms of a limerick:

Advertisement

Dear Sir, I went south:

As far as Portsmouth,

And found a most charming old woman,

Delightfully void

Of all that’s enjoyed

By the animal vaguely called human.

She has but one jaw,

Has teeth like a saw,

Her ears and her eyes I delight in:

The one could not hear

Tho’ a cannon were near,

The others are holes with no sight in….

And so on. “When she showed the verses to Chev,” Showalter informs us, “he was not amused.” It was probably at this moment that the ambitious Lydgate-like doctor began to suspect he had unwittingly married a flighty Rosamond.

George Eliot’s unhappy couple was not based on the Howes, whom she didn’t know. But Charles Dickens and Henry James knew them both, and also knew a great deal about them. So it is tempting to view all sorts of Dickensian and Jamesian female characters as having some affinity with Julia Ward Howe: from David Copperfield’s Dora, prettily yet ineffectually attending to household duties, to Mrs. Jellyby in Bleak House, ignoring her own children in order to champion the cause of faraway strangers; and from Verena Tarrant, The Bostonians’ public speaker on women’s rights, to the intrepid journalist Henrietta Stackpole in The Portrait of a Lady—or even that novel’s own central figure, the American heiress who chooses exactly the wrong husband.

Certainly Julia’s contemporaries were aware of the possible analogies. According to Showalter, Annie Fields (about whom Julia Howe had written an insulting and self-aggrandizing article) commented to some Boston friends that Julia resembled Mrs. Jellyby, “bursting in upon a newly organized society of working women ‘like a whirlwind.’” And we know that Henry James, who became a close friend of Julia’s daughter Maud, took at least one anecdote Maud had told him about her mother and converted it into a short story, “The Beldonald Holbein.” Might not other heroines of his have been suggested by the same evocative character?

By the time James was at work on The Bostonians and The Portrait of a Lady, in the 1880s, Julia Ward Howe had already emerged as one of the major female figures of her time. She was best known, in this post-Chev period, as a leader of the women’s rights movement and a speaker and writer on various subjects of public importance. But even as she branched out on her own, her greatest fame continued to rest on something she had done well before her husband’s death in 1876—an achievement that was intricately linked to Chev’s own abolitionist and political undertakings.

“The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” which Julia Ward Howe wrote in the midst of the Civil War, was based on events she witnessed in and near the national capital while on a visit there with Chev. He had been serving as a member of the US Sanitary Commission (a position he hoped, futilely, would lead to a diplomatic appointment), and in 1861 he brought Julia along when he went to Washington to attend commission meetings. While Chev was at his meetings, Julia visited nearby hospitals and army camps in the company of two Unitarian ministers. One day, as they were driving back to Washington surrounded by Yankee soldiers, she and her companions started singing “John Brown’s Body,” which had become something of an unofficial anthem among the Northern troops. The soldiers responded with enthusiasm, causing one of the ministers to say to Julia, “Mrs. Howe, why do you not write some good words to this stirring tune?” Those verses, she always insisted, came to her unbidden in a dream she had that very night; after thinking through each stanza in the early light of dawn, she rose from her bed to write them all down.

It has never been clear why “The Battle Hymn” took off the way it did—its high-flown poetry is not particularly good, its meanings are sometimes impenetrable, and the emotions it expresses verge on the demonically violent. But its success must have had something to do with the way the poem fit the popular tune of “John Brown’s Body.” That tribute to the martyred abolitionist (itself based on an earlier folk hymn called “Canaan’s Happy Shore”) had its own tendency toward ghoulish violence, celebrating as it did the dead body of the man who had been executed for leading the Harper’s Ferry slave revolt in 1859. It was in the Civil War itself that Brown’s soul went marching on, so the borrowing of his tune for an inflammatory Northern anthem made a certain amount of sense. The personal connection between the Howes and John Brown also contributed to the piquancy of the situation, for Chev and Julia had entertained Brown at their house, and Chev had even donated $50 toward his abolitionist cause (a link that led the otherwise staunch Howe to flee the country during Brown’s trial, when he too seemed briefly at risk of prosecution).

Supporting John Brown, though risky, was one of Chev’s better calls. As a fervent philanthropist and public do-gooder, he often ended up on the wrong side of history. In discussions about the education of the deaf, for instance, he argued that lip-reading was more useful than sign language. Confronting prison conditions, he insisted that solitary confinement was preferable to collective holding cells. And in a final error of judgment, he advised President Grant in 1871 that the inhabitants of the Dominican Republic were longing to have their country annexed by the United States.

Earlier, in 1866, he had tried to get General Grant, President Johnson, and Lafayette Foster, President pro tem of the Senate, to appoint him as an emissary to Greece. He did not get the post, causing Julia to write a poem titled “To S.G.H. on his failure to receive a Grecian mission which he had been led to think might be offered to him, 1866.” Though earlier biographers allege that she wrote the poem to comfort him, Showalter shrewdly observes that “she did not try to publish the poem; Chev would have been livid to see himself described by his wife as failing, especially when she seemed to be succeeding.”

Being livid had become Chev’s standard response to her poetry, and with good reason. In December 1853, Julia had brought out her first book of poetry, Passion-Flowers, without giving Chev any warning that it was about to appear. The poems dealt quite openly with emotional material from her own life. Some referred to a love affair (almost certainly unconsummated, and probably somewhat one-sided) that she had with an American named Horace Binney Wallace in 1850–1851, when she was in Rome without Chev, leaving their two older children behind in his care and taking only the younger two. Other poems alluded to her despair at Wallace’s recent suicide in Paris. Still others exposed a relationship that closely resembled her marriage, where images of imprisonment and oppression were linked to the male figure.

The book had been brought out anonymously, but everyone knew the poems were by Julia Ward Howe—and this was intentional, as Julia’s pleasure at its fame and success suggested. As if to heighten the agony for Chev, his close friend Longfellow had helped Julia secretly find a publisher, Ticknor and Fields, who had recently rejected a manuscript by Chev himself. The critic and biographer Gary Williams, who calls Passion-Flowers “one of the benchmarks of antebellum literary achievement” because of its “intensity,” “audacity,” and “emotional and technical range,” also describes it as “an instrument of revenge.”

Chev clearly took it as such, and his anger at the public humiliation and public defiance was apparently the only “bitter drop” in Julia’s happiness about her success. She blithely hoped his resentment would blow over, and was shocked when, about a month after the book’s publication, he confronted her with his request for a divorce. “His dream was to marry again—some young girl who would love him supremely,” Julia wrote to her sister Louisa. But instead of snatching at the offered freedom, Julia capitulated, agreeing to stay with him under his restrictive terms. “Before God, Louisa, I thought it my real duty to give up everything that was dear and sacred to me, rather than be forced to leave two of my children, and those two the dearest, Julia and Harry.”

It might seem enlightened for Chev to have offered to share the children equally, with him taking two and her taking two; that, after all, was how Julia herself had arranged things during her year in Rome. But clearly she had her own reasons for wanting to keep the marriage intact, reasons that may have included her suspicion that some “young girl who would love him supremely” was already waiting in the wings. (As it turned out, she was right about that: he confessed to at least one such intense and fully sexual affair on his deathbed.)

This cycle—of his anger, her resentment, and her rebellion—was to keep repeating itself for their remaining twenty-three years together. If her biographers are right, the pitched battle between Chev and Julia may have been part of what fueled her later achievements, even as it was also the impediment that prevented her from achieving more.

Her literary accomplishments formed a good part of her eventual reputation. In 1908, Julia Ward Howe was the first woman elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters; another was not inducted for twenty-two years. Was she really so much better a writer than everyone else? Showalter considers her “a poet with the irresistible force of her talent, the subversive intellect of an Emily Dickinson, the political and philosophical interests of an Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and the passionate emotions of a Sylvia Plath.” This seems to me vastly overstated. I can barely make it through her poetry, and I haven’t even attempted to read The Hermaphrodite, a strange, fragmented manuscript that Julia worked on from 1846 onward but then hid away, only to have it unearthed in the late twentieth century and released as an unfinished novel. (The subject was apparently suggested to her by the time she spent at the Villa Borghese in Rome looking at the statue of The Sleeping Hermaphrodite—a version of which, coincidentally, recently came to New York as part of the marvelous Pergamon show at the Met.*)

We needn’t blow her talents out of proportion to find her admirable. Julia Ward Howe was a nineteenth-century woman struggling against all odds to express herself, and she greatly helped others to express themselves as well. She was strong and effective if not very likable. She contracted a marriage in which her husband’s success was at first more important than her own, though in the end she emerged famous and triumphant. When she kept her maiden name as her middle name, she established a form of independence that women after her were to take even further. She made errors of judgment at times, but she learned when and how to apologize for them. She endured her spouse’s occasional crudeness and infidelity, adopting the useful parts of his humanitarian politics and rejecting his more blinkered ideas while going on to formulate a new politics of her own. Such women still matter enormously in American public life—occasionally irritating, always indispensable.

-

*

See G.W. Bowersock’s review in these pages, June 23, 2016. ↩