Those of us who fight global poverty share a guilty secret: our cause got more attention and resources after September 11, 2001. It soon became clear that there would be an alliance between the “War on Poverty” and the “War on Terror.”

But this boost for the cause of the world’s poor came at a price for the values of global humanitarian efforts—the loose alliance of private charities, international organizations, and government aid agencies that give aid to poor countries. The connection between the wars on poverty and terror had two unintentional negative consequences that are becoming more evident as time passes. First, it deepened negative stereotypes about the poor that contribute to the current wave of xenophobia against refugees and immigrants in the US and Europe—attitudes suggested by the Brexit vote and the rise of Donald Trump and other far-right leaders. Second, in justifying support for dictatorial regimes, the connection discredited Western advocacy of the ideals of democracy worldwide. We have Trump expressing admiration for authoritarian rulers like Vladimir Putin and in some ways aspiring to be an autocrat himself.

The negative stereotypes about the world’s poor got worse during the War on Terror because it was alleged that poverty was the principal cause of terrorism. When he spoke to an international aid conference in March 2002, George W. Bush said that “we fight against poverty because hope is an answer to terror.” In July 2005, after the terrorist attack on the London Underground, British Prime Minister Tony Blair said:

Ultimately what we now know, if we did not before, is that where there is extremism, fanaticism or acute and appalling forms of poverty in one continent, the consequences no longer stay fixed in that continent.

The association of “wars” on terror with those on poverty persisted through changes in leaders and parties. In 2014, John Kerry said that “we have a huge common interest in dealing with this issue of poverty, which in many cases is the root cause of terrorism.”

As a result the US and UK governments have increased foreign aid to fight the poverty that was allegedly the root of terrorism. The same aid cemented alliances of the US and UK with frontline states in the War on Terror. The unintentional effect was to encourage a stereotype of poor people as terrorists. One well-known economist advising US and UK policy was Paul Collier, whose book The Bottom Billion (2007) conveyed what has become typical of the image of poor countries: “The countries at the bottom coexist with the twenty-first century, but their reality is the fourteenth century: civil war, plague, ignorance.”

There was also a private humanitarian response to September 11. A group of foreign policy experts led by Bill Gates Sr., the co-head of the Gates Foundation, formed the Initiative for Global Development (IGD) in 2003. The IGD aimed to persuade the US government to increase foreign aid. The senior Gates said at the time: “We will talk about the importance of alleviating extreme poverty as an economic and national security issue.” The Gates Foundation would itself spend many millions of dollars on aid for poor countries. The link between poverty and terror also helped private nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) fighting global poverty, like World Vision and Save the Children, raise more donations from the American public.

The idea that foreign aid would serve both development and defense increased the support for foreign aid both among those who cared principally about the War on Terror and those who cared principally about the War on Poverty. Daniel Glickman of the Bipartisan Policy Center summarized the double case for aid in 2010: “It protects us and is also the right thing to do.” Glickman observed that the national security rationale increased the support for aid among conservatives in Congress. Now the War on Terror was not just about killing terrorists, but about compassionately reducing the poverty that produced terrorists. The War on Poverty was allotted more resources; the budgets of all official aid agencies roughly doubled (with adjustments for inflation) between 2000 and 2014, as did the budgets of US and UK official aid agencies specifically.

Unfortunately for this politically convenient outcome, the idea that poverty is the root of terrorism never was based on concrete evidence. A considerable number of systematic studies by social scientists soon after September 11 failed to find a link between poverty and the propensities of young people to become terrorists. Researchers found that terrorists and their supporters were usually well above the poverty line and had secondary or higher education.1

While it may have sounded compassionate for the War on Terror to address poverty as a root of terrorism, this view also sustained the same kind of stereotype suggested by Collier—poor countries were seen as full of violence-prone peoples living under conditions comparable to the fourteenth century. It is not a long step from such a view to Trump’s saying that “we have to beat the savages.”

Advertisement

Data from Africa are a useful corrective to such stereotypes. While wars and terrorist attacks are happening in Africa and are tragic for their victims, the death rates from all war and terrorism across Africa in 2015 was .003 percent of the population. Moreover, violence is decreasing, not increasing. The peak for war deaths in sub-Saharan Africa was in 1999, when the Angolan civil war and the war between Eritrea and Ethiopia accounted for six times the deaths from all war and terrorism in Africa in 2015.2

Stereotypes of poor people as terrorists also fail to grasp how rare terrorism is relative to the populations that are alleged to include relatively high numbers of terrorists. The estimated number of fighters for Boko Haram in Nigeria and al-Shabab in Somalia is about nine thousand each, compared to a sub-Saharan Africa population of nearly one billion. The estimate for the Islamic State is about 31,500 fighters, compared to the global Muslim population of 1.6 billion. We know that terrorists are capable of terrible atrocities that capture the world’s attention, but according to these numbers, Africans and Muslims are more likely to be doctors available to treat victims of terrorists than to be terrorists.

Correcting the false stereotypes of the poor as terrorists may disrupt what many have advocated as an alliance of the War on Terror with the War on Poverty. Yet it is important that stereotypes be corrected when, for example, they play into the hands of Trump’s racist portrayals of Muslims and other immigrants from poor countries. Such stereotypes also encourage the ugly backlash against immigrants from Africa and the Middle East that was a cause of the Brexit vote and other anti-immigrant movements in the European Union.

The second problem with efforts to form an alliance between the War on Poverty and the War on Terror was the damage to the cause of global democracy. This connection of official aid agencies and private charities with counterterrorism efforts by the US and UK redirected aid money to some of the most autocratic, corrupt, and oppressive regimes in the world, among them Ethiopia and Uganda.

It is hard for the West to make the case for democratic values when official Western aid donors give money and legitimacy to autocrats who kill, starve, or imprison their own democratic activists. The worldwide battle for democratic values—from Hungary to Poland to Hong Kong to Turkey to Russia to China to Africa—is contradicted and set back if Western government aid goes to dictatorships that suppress even mild forms of dissent.

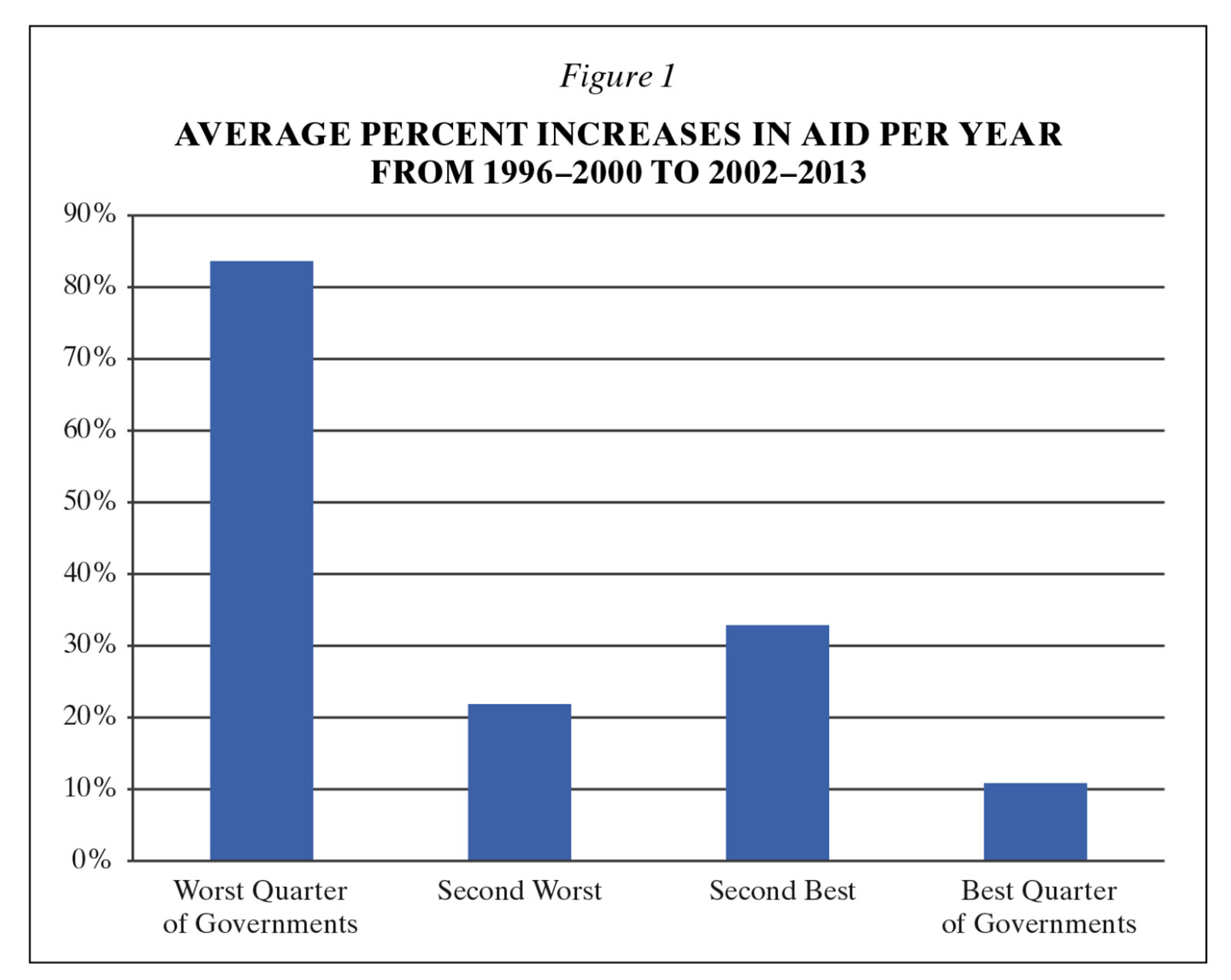

The distribution of foreign aid before September 11 was already too indifferent to dictators. But things got much worse when the new conceptions of aid following September 11 positively rewarded oppressive governments. The World Bank’s own measure of bad government ranks most countries in the world by averaging multiple factors including autocracy, corruption, political violence, and absence of rule of law. If we use this measure to divide aid recipients into the best and worst quartiles of governments between 2002 and 2013, the worst-governed places on average actually got the largest percent increases in aid after September 11, compared to the pre-war period between 1996 and 2000 (see Figure 1).

What happened? The War on Terror created a new justification for redirecting foreign aid to some of the world’s worst governments. That justification was that aid should take on the task of “fixing failed states”—places in which a government is dysfunctional and terrorism is alleged to flourish as a result. Fixing Failed States was the title of an influential 2008 book by two former World Bank economists. One of them was Ashraf Ghani, who has since become the president of the still seemingly unfixed state of Afghanistan.

The euphemism “fragile states” later replaced the more insulting phrase “failed states.” What does it actually mean? The most popular measure, the Fragile States Index calculated by the Fund for Peace and Foreign Policy, covers a diversity of issues and circumstances—the 2015 edition of the index mentioned Ukraine, Ferguson (Missouri), the US government shutdown, ebola, and Syria.

As software developers might say, perhaps the very vagueness of the “fragile state” label was not a “bug” but a feature. It was a flexible phrase used to justify giving aid to some very bad governments in the illusory hope of “fixing” them, which turned out to be useful for two separate purposes. First, it rationalized aid to often extremely repressive allies in the War on Terror like Tajikistan and Uzbekistan in Central Asia, and Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Uganda in Africa. Second, the project of rescuing fragile states gave increased official development aid to war-torn places where the US and UK perceived vital national security interests—such as Iraq, Afghanistan, and Somalia. These two groups plausibly explain why aid tends to reward bad government, as shown in Figure 1.

Advertisement

Aid organizations had very good intentions. They wanted to alleviate the heartbreaking misery of those living in the most repressive and war-torn environments. Yet we live in a world of difficult tradeoffs. Aid dollars are limited and those supplying aid must be realistic about circumstances where aid is unlikely to reach the intended beneficiaries. Well-intentioned aid does no good and may even do harm if it is confiscated by a warlord or diverted to pay for more political repression. A recent study found that food aid can actually increase violence in some civil wars.3

Moreover, aid to the worst regimes is implicitly taken away from less bad regimes where aid is more likely to help the poor—places where there is still poverty, but there is more (although highly imperfect) democracy and peace—for example, Ghana and India instead of Ethiopia and Uganda. Even if humanitarian organizations had objected to such tough realism and wanted to continue some aid to the worst governments, there is still no reason to have actually increased aid to the oppressive regimes compared to other aid recipients.

The large NGOs giving private philanthropy to poor countries also went along with a shift of their efforts toward “fragile states.” One of the largest NGOs, World Vision, which is based near Seattle, said on its website in April 2016 that “fragile states/contexts are where relief and development agencies need to concentrate their efforts.”

World Vision accepted the position of the US and UK governments that defense and development are complementary: “Development and peacebuilding approaches [i.e., military intervention] can work together to reach the people in greatest need and help end conflicts.” The leaders of World Vision—which contributes more than $800 million per year to international humanitarian aid—announced that they themselves have “elevated our focus on fragile states over the past five years.” World Vision has the best of intentions: “We feel called to go to all these places and help children where they are most vulnerable.” At the same time, the organization itself acts as an aid contractor receiving US government funding. In 2015, government grants made up $172 million of World Vision’s funding.

Bill Gates Jr. was among those who believe “the world will be a safer place” if there is less world poverty. He also noted “that if the United States plays a role in helping to create prosperous societies, we will have friends to call on in times of need.” So perhaps it was not unexpected that the Gates Foundation supported a major US ally, the Ethiopian autocrat Meles Zenawi. Meles led a rare Christian-majority nation surrounded in the Horn of Africa by countries with largely Muslim populations, and Meles was a declared enemy of the Somali terrorists. Gates’s foundation has spent $265 million on health and development in Ethiopia over the last decade, and there is much to admire about these efforts.

Still, serious questions can be raised about Gates’s praise of Meles’s regime in 2013 for having “made real progress in helping the people of Ethiopia,” by “setting clear goals” for health and reducing poverty, then “measuring results, and then using those measurements to continually refine our approach,” i.e., the approach of the Gates Foundation. Although Gates is well intentioned, he does not seem to realize the ways his praise for a repressive autocrat affect the global controversy over democratic values.

Unfortunately, Meles had another dimension besides his alleged success in economic development. He was also engaged in large-scale repression of human rights, having shot down unarmed student demonstrators in the streets in 2005 after rigged elections. In 2010, Human Rights Watch accused Meles of manipulating food aid from Western official aid agencies to starve the opposition—directing food relief only to his loyal supporters. Official donors, such as the UK Department for International Development (DFID), at first promised to investigate but never did.4

In 2012, to take only one of many examples, Meles sentenced a peaceful blogger and dissident named Eskinder Nega to jail for eighteen years. In the Gambela region in 2012, Meles began a program named Villagization that forced farmers off their land at gunpoint and made them move to government “model villages” that lacked essentials including water. There were allegations of rapes and murders of farmers who resisted, and many refugees fled to Kenya to escape the program. One of those refugees even sued DFID in court for supporting the forced resettlement scheme that had harmed him and his neighbors so much. (DFID quietly dropped its support of Villagization before the suit came to trial, but continues to give the Ethiopian government large amounts of aid for other projects.) Meles died in 2012, but his brutal party remained in power, while revolt and repression kept escalating. According to a report in The Economist of October 15, “over 500 people have been killed since last November” and “tens of thousands have been detained.”

Another ally of the United States and United Kingdom in the War on Terror is Uganda’s dictator, Yoweri Museveni, who in February 2016 extended his thirty years in power with a rigged reelection.5 Ugandan troops make up the largest national contingent of peacekeeping forces fighting the al-Shabab terrorists in Somalia. Museveni gets large amounts of US, UK, and World Bank foreign aid—and much tolerance of his repression of human rights—as a reward for being an ally. A World Bank forestry project in the district of Mubende, Uganda, in 2010 directly resettled 20,000 farmers at gunpoint. It was the subject of a dramatic front-page story in The New York Times over a year later, in September 2011. The World Bank, apparently embarrassed by the Times story, promised to investigate its own part in the Mubende tragedy. It never carried out that investigation and suffered no consequences, another example of how the War on Terror can confer impunity on the donors who finance “fragile states” that are allies of the US and UK.

We should also not underestimate the effect of Western nations financially and intellectually supporting dictators on the global debate on human rights and democracy. When the World Bank fails to protect the political and economic rights of its own intended beneficiaries in Mubende, it fails to support human rights and democratic values. When the US and UK governments ignored the manipulation of their own food aid to starve Ethiopian dissidents, they seemed to imply that democratic rights are not a fundamental concern for them.

Another common but mistaken stereotype is that Ethiopians, Ugandans, and other poor people care only about their material poverty and not about fundamental rights. Human Rights Watch noted that official donors defended their complicity in political manipulation of Ethiopian food aid on the grounds that “economic progress outweighs individual political freedoms.”6 But in their book Africa Uprising (2015), Adam Branch and Zachariah Mampilly document more than ninety political protests in forty African countries during the past decade, protests for more rights and less oppression and corruption.

The War on Terror had the effect of offering the War on Poverty additional funding in return for an alliance based on the unproven notion that fighting poverty would also fight terrorism. This alliance now looks like a bad bargain, both for Western humanitarians and for the world’s poor. Mistaken accounts linking terrorism to poverty during the War on Terror supported negative stereotypes of poor people and particularly refugees; such allegations contributed in at least some way to today’s resurgent xenophobia in the US and Europe. NGO and government aid leaders gave support—both rhetorical and financial—to Western dictatorial allies, sabotaging the promotion of democratic values worldwide (or even today at home). Vladimir Putin mocked Western efforts in his address to the UN General Assembly on September 29, 2015: “Instead of the triumph of democracy and progress, we got violence, poverty and social disaster. Nobody cares a bit about human rights.” It is sad that it is now hard to come up with a rejoinder to a ruthless autocrat like Putin concerning Western efforts to help poor nations.

It is time to end the alliance of the War on Poverty with the War on Terror. All of us who want to support Western humanitarian efforts should make clear our political independence from our own governments’ national security programs. Humanitarians should not condone violating the basic rights of poor people abroad—or of immigrants at home—because of the War on Terror. Humanitarians must find their voice again to say that both at home and abroad all men and women, rich and poor, Christian and Muslim, white and black, are indeed created equal.

-

1

Alberto Abadie, “Poverty, Political Freedom, and the Roots of Terrorism,” NBER Working Paper No. 1085g, October 2004; Alan B. Krueger and Jitka Malečková, “Education, Poverty and Terrorism: Is There a Causal Connection?” The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 17, No. 4 (Fall, 2003); James A. Piazza, “Rooted in Poverty?: Terrorism, Poor Economic Development, and Social Cleavages,” Terrorism and Political Violence, Vol. 18, No. 1 (2006). ↩

-

2

Data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, www.acleddata.com/data/acled-versions-1-5-data-1997-2014/. ↩

-

3

Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian, “US Food Aid and Civil Conflict,” American Economic Review, Vol. 104, No. 6 (2014). ↩

-

4

Jan Egeland, “Ethiopia: Letter Regarding UK Development Assistance,” Human Rights Watch, September 29, 2011. ↩

-

5

See Helen Epstein, “The Cost of Fake Democracy,” NYR Daily, May 16, 2016, and “Uganda: When Democracy Doesn’t Count,” NYR Daily, January 25, 2016. ↩

-

6

“Development without Freedom: How Aid Underwrites Repression in Ethiopia,” Human Rights Watch, October 19, 2010. ↩