In some parts of the world, it is still possible to silence a journalist with a sharp blow to the side of the head. But as newspapers the world over struggle with the financial disruption of digital technologies, governments are finding new ways of controlling the press. Murder is messy. Money is tidy.

John Kituyi, a brave, persistent local newspaper editor in Kenya, was a victim of the old-fashioned method in April 2015, when the sixty-two-year-old from Eldoret in western Kenya was killed while preparing to publish the results of an investigation that could have embarrassed leading figures in Kenya’s national government. An assailant with a blunt object brought Kituyi’s life, the story, and the newspaper itself to a sudden end.

Though the threat of such physical violence remains a concern for journalists even in one of Africa’s most developed nations, a less bloody mechanism for constraining the free media is increasingly being used. Murder can lead to awkward questions, and if the victim is a journalist or a lawyer, may attract international attention. But as revenues drain away from traditional media because of the inroads of digital technologies, the use of financially induced self-censorship—we might abbreviate it to “fiscing”—can also ensure that journalists are more “reasonable” in their reporting.

That could well have been the Kenyan government’s actual motive when it set up a single government agency in 2015 to act as a conduit for all advertising in the country’s newspapers, enabling a centralized body to turn the flow of money on or off. Journalists in Kenya say the country’s political classes are ensuring that “unhelpful” coverage will be effectively penalized—i.e., that the money for reporting will dry up.

Like their counterparts around the world, Kenyan newspapers are feeling the punishing economic consequences of readers and revenues moving online. The income the media organizations receive from all Kenyan government sources is estimated to represent at least 25 percent of their total advertising revenue—or would, if the government actually paid. In fact, the new advertising agency is not paying the bills. The failure of the money to arrive is, according to Tom Mshindi, editor in chief of the country’s most influential newspaper, the Nation in Nairobi, “putting a huge amount of stress on our bottom lines, our operational, our cash flows, and everything else.” The second-largest newspaper group in Kenya, the Standard, issued a warning in August 2015 predicting a 25 percent fall in revenues. Other papers are also seeing sharply declining revenues.

Mshindi’s former colleague at the Nation, Linus Gitahi, who had been CEO for nearly nine years when he left in 2015, is no longer involved in the media business, but told me he is well aware of how fiscing works. Waving his wallet in the air from side to side, he said, “Oh, you’re the guy who had that headline yesterday and you want us to talk advertising this morning? Tell it to the birds.”

This is the art of fiscing: no one directly censors anyone. The newspapers respond to the potential withholding of revenue by censoring themselves.

Since independence, Kenya has at times been something of a beacon of free speech in Africa, but David Makali, director of the Media Institute in Nairobi and a prominent commentator on the press, compares the present situation with the era of former president Mwai Kibaki (“a bit oppressive, but subtle”) and that of Daniel arap Moi (“brutal suppression”).

Today, Makali says, “These new guys have basically taken to co-opting journalists. They’ve perfected the art of censorship because they intervene at the very inside, using the state levers of advertising and manipulation through resources to make sure that you won’t publish anything they don’t like. You publish, the sanctions are immediate.”

One attraction of fiscing for government is that it is difficult to prove that a newspaper censored itself as a result of financial pressure. That star journalist who didn’t have his contract renewed? A government spokesman will shrug his shoulders and say it has nothing to do with him. Most, though not all, editors are too proud to admit that they will quietly suppress a particular story for fear of losing revenues.

But high-profile editorial figures have been dispatched from their jobs in recent months following work that did not please Kenya’s highest level of government, known as State House. As a result, important stories remain untold or neglected.

John Kituyi is not the only member of the media to have lost his life recently, yet senior journalists, many of whom were granted anonymity during interviews for this article, frankly confess that they now soft-pedal investigations. In short, they concede that fiscing is working.

The health of the Kenyan media matters particularly on a continent where truly free speech is rare and becoming rarer still. The journalism coming out of Nairobi since independence in 1963 has often been robust and relatively unfettered. Compare the country’s newspapers even today with those in the neighboring countries in the region and the Kenyan press still shines, if not as brightly. There is a fairly new constitution and, until now, a Supreme Court willing to take account of it.

Advertisement

Ask Denis Galava, however, a former senior editor at the Nation, about how he lost his job after writing a New Year editorial that displeased State House. Talk to Gado, one of the world’s most trenchant cartoonists, who found that his contract at the Nation was not renewed this year after he upset politicians in Kenya and beyond. Sit down with Robert Wanjala Kituyi and hear him recall in a whispered voice the investigation that led to his own harassment and his brother’s murder. Ask editors and reporters why almost no one in the Kenyan media has aggressively sought to investigate the reverses the Kenyan army has suffered in fighting the jihadist terror group al-Shabaab. A picture emerges of a press that is feeling economically uncertain and editorially intimidated.

The government’s extreme sensitivity to criticism has its roots in the 2010 decision of the International Criminal Court (ICC) to prosecute the current president, Uhuru Kenyatta, and his deputy, William Ruto, over the violence that erupted following the 2007 elections. The troubles broke out after Raila Odinga, the leader of the Orange Democratic Movement, was denied victory under controversial circumstances. He was on course to win the election—but at the eleventh hour, and to general disbelief, Mwai Kibaki was announced the victor.

The official death toll in the violence was put at 1,200 people, with 500,000 people displaced. In the subsequent ICC investigation, then Deputy Prime Minister Kenyatta, who opposed Odinga, faced five counts of crimes against humanity, including inciting murder and rape. Ruto was charged with being an “indirect co-perpetrator,” with members of the Kalenjin ethnic group, in committing murder, deportation, torture, and persecution in and around his hometown of Eldoret.

President Barack Obama lent his support to the charges, urging Kenya’s leaders to cooperate fully with the ICC investigation. Once in power, after 2013, Kenyatta and Ruto had other ideas. They not only rejected all the allegations but denounced the ICC as “the toy of imperial powers.” The case eventually collapsed after many witnesses withdrew or, in some cases, disappeared or died. According to the ICC, no fewer than seventeen witnesses against Ruto alone withdrew their testimony.

John-Allan Namu, an investigative reporter who set up an online-based independent investigative operation after leaving Kenya Television Network, talked to me about the stories of witness disappearances, interference, and murder: “If told definitively,” he said, “it would be one of the most explosive stories yet, considering how many people died in the post-election violence. But who is going to go up against the president and the deputy president?”

One editor who was interested in getting the facts was John Kituyi, who started his own newspaper, the Mirror Weekly, in Eldoret after becoming frustrated over stories that never saw the light of day at his previous employers. His persistence in investigating corporate power had landed him in jail for months for criminal libel in 2005 after he wrote about alleged human rights violations at a factory. Kituyi employed his brother, Robert, who was nearly thirty years his junior, to investigate the case against Ruto.

I met Robert Kituyi for lunch at an Italian restaurant in a shopping mall near the center of Nairobi. He ate little as he embarked on a long narrative about how he and his brother—whom he insisted on calling “my editor”—patiently followed the proceedings of the ICC case against the most powerful politician in the region.

As Robert pursued the story, he says he began receiving serious threats on his life, and he decided to flee the town. Within a few days of publishing the first of two stories about witness interference, John Kituyi was dead. By the time Robert got to his older brother’s laptop in the newspaper office in Eldoret, the hard drive was missing.

The head and two front teeth of his brother and editor had been smashed by something heavy and lethal, and the final story had disappeared. Soon afterward, the newspaper closed. More than a year later, there has been little progress in the case.

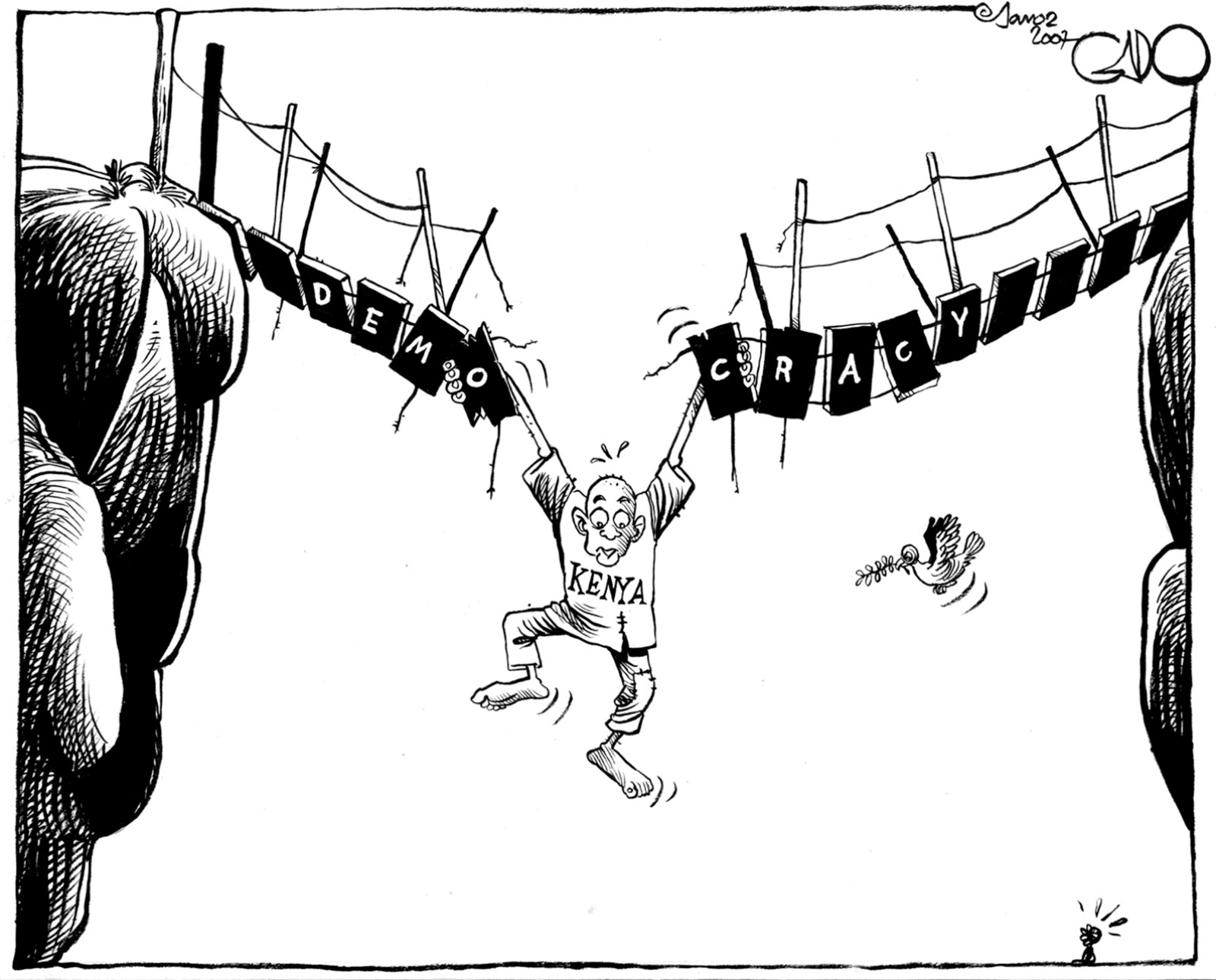

Godfrey Mwampembwa, who goes by the name Gado, is the best-known cartoonist in East Africa. Tanzanian by birth, he abandoned studies as an architect after entering a cartoon competition run by the Nation in Nairobi. He joined the paper in 1992 and has been ridiculing politicians for it, and for its sister paper, the East African, ever since.

Advertisement

Gado’s trademark is to find a visual gag (often very offensive) to identify his subjects. Uhuru Kenyatta, son of the founding president, Jomo, was a young, inexperienced politician when he first took office, so Gado drew him in diapers and with a feeding bottle. When the ICC pressed charges against Kenyatta and Ruto, Gado began caricaturing the president and deputy president with a penal ball and chain attached to their ankles.

Jared Nyataya/Nation Media Group

Journalists lighting candles in memory of newspaper editor John Kituyi on World Press Freedom Day, Eldoret, Kenya, May 2016. Kituyi was killed the year before while preparing to publish the results of an investigation that, according to Alan Rusbridger, ‘could have embarrassed leading figures in Kenya’s national government.’

Then, in January 2015, Gado drew a cartoon of Tanzanian President Jakaya Kikwete surrounded by beautiful women, three of whom were labeled Cronyism, Incompetence, and Corruption. The cartoon did in Gado. The Tanzanian government’s response to the satire of its president was swift and sharp: it banned the East African from distribution in the country, claiming to have suddenly discovered that the paper was unregistered.

The Nation CEO, Linus Gitahi, faced a dilemma. The paper had forty employees in Tanzania. Did he ditch them or “deal with Gado”? His solution was to offer Gado a year off on paid leave. “I told Gado, ‘this guy is literally asking for your head, right? What we do is we give him your head, in the sense that we give you a study leave. If there was ever a time you wanted to write a book, this is it.’”

Gado was not displeased to be allowed a fully paid yearlong break. Within a week of the cartoon’s appearance, the East African published a groveling apology for depicting the Tanzanian president in “a bad light.” The drawing “should not have been published except for a rare lapse in our otherwise rigorous gatekeeping process,” the editorial noted.

Honor was satisfied. But it was eight months before the East African was allowed back on the streets of Dar es Salaam. And Gado had an unpleasant shock in store.

During Gado’s absence from cartooning, relations between the government and the press hardened. The next flare-up came at the 2016 New Year, while Gado was on his forced sabbatical. This time, the problem was an editorial in the Saturday edition of the Nation.

The offending piece, an editorial known as a “leader” and framed as a personal letter to Kenyatta, was written by Denis Galava, a soft-spoken, erudite forty-one-year-old who had worked in a variety of senior executive positions, including editorial writer, since joining the Nation in 2010. In the absence of senior editors, many of whom were on holiday, Galava says, he discussed the theme with colleagues before writing it on Friday. The piece, which Galava said took him about thirty minutes to write, began bluntly:

Your Excellency, 2015 was a bad year for Kenya. All the pillars of our nationhood were tested and most were found wanting. Some collapsed, some were seriously weakened, while others were desecrated beyond repair.

The following morning the editorial started to appear on social media. “My senior colleagues began calling me and saying that the board chairman is livid,” Galava says. His colleagues told him that people from State House had been demanding to know who had written the editorial. “They were asking, ‘You tell us who was working yesterday, who’s this trying to sabotage us?’”

By Monday, Galava had received a call from a friend at the State House: “Denis,” Galava recalls the person saying, “I’m really sorry to tell you this, that editorial, you are going to be suspended at least—but you are toast, it’s really unfortunate.” The prediction turned out to be accurate: Galava was sacked and is now suing the company for wrongful dismissal.

The Nation’s current editor in chief, Tom Mshindi, says he is reluctant to discuss the case because of the forthcoming legal action, but he denies receiving any calls complaining about the article and says, “Just suffice it to say that there were some procedural things that were not followed in terms of the way we do clearances on matters that are published and, particularly, very sacrosanct things like editorials.”

One former Nation editor who asked not to be named says there is no way the paper would have sacked Galava unless someone complained. “When the shit hits the fan, you’ve got to stand together,” the person said. Galava has little doubt that the pressures on the Nation—both through advertising and on behalf of the wider interests of the Aga Khan, the leader of the Ismaili Shiite sect of Islam, who is the paper’s largest shareholder—are being felt. “If you speak to people in the Aga Khan community, in the Ismaili community, they often will tell you the Nation has become a liability.”

“But the thing which…now everyone knows in Kenya whether inside or outside the Nation or the Standard or the Star [is] that you can’t touch the president. The consequences of touching the presidency are dire,” Galava says.

This hardening of the government mood was disturbing for Gado as he approached the end of his sabbatical. By then, both the former editor, Joseph Odindo, and the former CEO, Linus Gitahi, had moved on. In February 2016, just a month after Galava’s suspension, Gado was told he wasn’t wanted back at the Nation. He says colleagues told him he had been “marked.” His twenty-three-year career with the Nation was over.

Mshindi, who, as editor in chief, broke the bad news to Gado, chooses his words carefully when asked about the decision to terminate Gado’s contract:

This is not a decision usually taken by one person, this was a collective decision that was taken by more than just one office, because he was a very senior person. I mean,… I can’t just wake up, myself, Tom, and start sacking editors. It’s not done that way.

Does that mean that the decision was made by the editorial board? “Well, it’s a management decision,” Mshindi said. “The board is a policy-making organ; it doesn’t come into these decisions.”

The firings of Gado and Galava, combined with fiscing, have affected staff morale at the Nation, and one very senior executive says, on condition of anonymity, that the newspaper has had to plead with the government’s advertising authority to be paid the money it’s owed. “Inevitably, it has an impact on stories,” he says. “The guys on the second floor [the commercial department, which includes advertising] come along and say, ‘These stories you are writing are making it hard for us.’”

Once newspaper managements appeared to give in to government pressure, the belief spread that stories critical of the corporate world would be similarly unwelcome. All the editors and senior executives I’ve spoken with, for example, say they would not think of running a negative story about Kenya’s largest corporation, Safaricom, for fear of losing advertising revenues. The senior Nation editor says:

We’re retrenching, so there’s no security of jobs any more. Everyone understands there are no jobs out there. If the government paid us what they owed us, then that would help. But the message goes out loud and clear…go easy on government and corporates. Reporters get the message. They understand what stories are off-limits so they go for safer stories.

Officials with the Government Advertising Agency readily admit that the agency owes media companies a great deal of money. Denis Chebitwey, director of public communications at the Ministry of Information, Communication and Technology, which runs the GAA, estimates the agency owes media companies more than £5 million, adding, “But that will be paid.” Mshindi estimates that twice that sum could in fact be owed. Chebitwey insists he has never called an editor either to complain about coverage or to influence the way a story is reported.

My first opportunity to ask for an official account comes when I meet with State House spokesperson Manoah Esipisu, a former Reuters reporter who studied journalism at City University in London. Dressed in a gray sweater, he tilts back in his chair in an office on the first floor of the whitewashed former official colonial residence of the governor of East Africa.

I ask him about the charge that the GAA is being used to put pressure on media companies. The reality, he says, is mundane: the government has a huge budget deficit and the GAA is not the only official department struggling to pay its bills.

We move on to the sacking of Gado. Esipisu denies the government caused it and distances himself, in words that seem to have been carefully chosen, from the idea that this had anything to do with pressure from government. “I haven’t seen any evidence of such pressure, even though I have heard stories of that pressure,” he says. “I think that it is easy to say ‘State House did this’…but, ultimately, it comes to proof. I mean, this building doesn’t make phone calls, people do. The administration did not ask for his sacking.”

“Did the administration complain about him?” I ask, and “What about the sacking of Denis Galava?”

Esipisu becomes more assertive, claiming that Galava replaced an editorial that was already typeset and ready to print—something that no one in the Nation’s management has said. “Galava did what people, ordinarily, don’t do in a newsroom, replacing an editorial that is already plated without consultation—that’s what I hear,” Esipisu says. “But would I ask that he be fired for that? No, I wouldn’t. That’s an internal management thing. If you publish stuff that you can’t stand by, that’s a problem.”

The legal system in Kenya has always represented a challenge for journalists, many of whom have complained about the use of libel (including criminal libel) laws to suppress their work. But the government of President Kenyatta has, since 2013, tried to introduce additional laws and regulatory mechanisms that could, if fully implemented, further erode the ability of the media to aggressively report on controversial subjects.

Most of the editors and writers I spoke with in Kenya say they are extremely anxious about the run-up to the next election in August 2017. “Now that we’re going into the elections, I think that political pressure is going to be open, very direct,” Odindo says.

John-Allan Namu, who is thirty-three, is part of the younger generation of Kenyans who have decided to move into new media to be able to work freely. “To be fair, our executives did try to defend us, but I think the pressure became too much,” he says. “I sort of made up my mind that, if I am going to be able to develop as a journalist, I can’t do it within the context of a mainstream media house.” Namu’s new online venture, called Africa Uncensored, has eight employees and is supported by donors and by content sold to media companies.

“Part of our Kenyan culture, a resilience and a resistance to wrong-doing and to encroachment on rights—that hasn’t yet disappeared,” Namu says.

And, I mean, this country has so much potential. Geographically, alone, we are equidistant from so many places in the world. We have great weather. We’ve got a great service industry. But it’s our rulership and, you know, some of the vices in society that are holding us back. There are a lot of people who either want us to speak about it or are doing something about it themselves, so I’m hopeful.

But in the end, Namu wonders how his little start-up will fare when “the rubber will meet the road and we have something that’s just untouchable.” He talks about the recent murder of Jacob Juma, a gadfly businessman and frequent user of social media who in January predicted his own death on Facebook for “my stand on corruption in gov’t.” He was shot ten times as he drove home to the Nairobi suburb of Karen on May 5, 2016.

In the past, the financial strength of the mainstream media would have conferred a level of protection upon reporters, Namu believes. But now, many journalists working for large media groups feel less confident of protection and those on the outside feel very vulnerable.

The Kenyan media—still, for all its frailties, a point of relative light in a troubled region—is discovering what it’s like when a government exploits the financial fragility of the press today. In that sense, Kenya may prove to be a different kind of beacon.