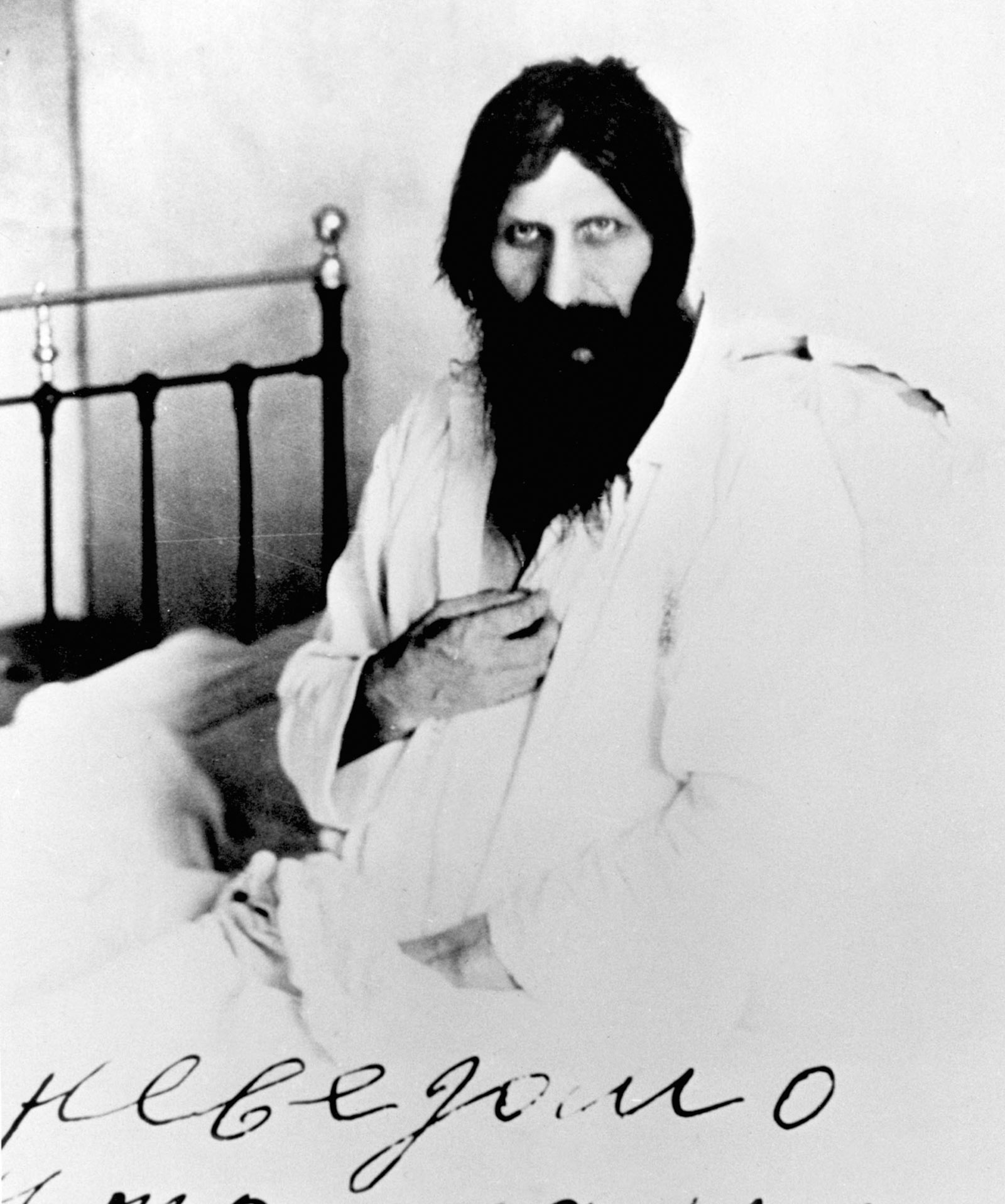

Divers brought up the frozen body of Gregory Rasputin from beneath the ice of the Malaya Nevka River in St. Petersburg on December 18, 1916. The wooden supports of the Large Petrovsky Bridge, from which his body had been thrown into the water, were stained with blood where he had hit his head on the way down. For several days a crowd of women gathered on the riverbank with bottles, pots, and buckets to collect the “holy water” sanctified by contact with his flesh.

A mystical belief in the healing powers of the “holy man” brought Rasputin to a powerful position at the Romanov court in its last disastrous years. Tsar Nicholas and Tsarina Alexandra saw him as a man of god and looked to him to cure their hemophiliac son, Tsarevich Alexis. But tales about his scandalous behavior with prostitutes, of sexual orgies with the tsarina, and wartime rumors that he was a German spy resulted in his murder by a group of three conspirators—the tsar’s cousin, Grand Duke Dmitry, Felix Yusupov, the husband of his niece, and Vladimir Purishkevich, the monarchist cofounder of the extreme nationalist Union of the Russian People—in a desperate attempt to save the monarchy.

Luring Rasputin to the cellar of the Yusupov Palace, the killers laced Rasputin’s drink with poison, shot him in the heart, and, when the bleeding victim miraculously revived and crawled out into the courtyard, or so the story goes, fired four more times, the last from close range into his forehead. Wrapped in heavy linen, Rasputin’s body was thrown into the river with his hands tied by a cord, but it kept on coming up, and when it was discovered later, floating underneath the icy surface, his arms were strangely locked above his head. The rumor quickly spread that even in the water Rasputin was not dead: somehow he had managed to untie his hands and make the sign of the cross.

So much of this story is based on hearsay and half-truths that it is practically impossible to separate the facts of Rasputin’s life from the fictions that have fixed its meaning in the historical memory and mythology of the Romanovs’ downfall. Douglas Smith sets about the task of distinguishing between them in Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs, which follows from his widely acclaimed book Former People (2012), an elegiac account of the aristocratic Sheremetev and Golitsyn dynasties in the revolutionary period. Yet he rightly keeps the two strands intertwined, for, as he explains in the introduction, it is the myths about Rasputin that make him an important historical figure:

The deeper I went into my research, the more convinced I became that one of the most important facts about Rasputin, the thing that made him such an extraordinary and powerful figure, was less what he was doing and more what everyone thought he was doing….

To separate Rasputin from his mythology, I came to realize, was to completely misunderstand him. There is no Rasputin without the stories about Rasputin. And so I have been diligent in searching out all these stories, be it those whispered among the courtiers in the Romanovs’ palaces, the salacious chatter wafting through the aristocratic salons of St. Petersburg, the titillating reports from the boulevard press, or the pornographic jokes exchanged among Russian merchants and soldiers. By following the talk about Rasputin I have been able to reconstruct how the myth of Rasputin was created, by whom, and why.

Smith’s discovery is hardly new. The intertwining of man and myth has long been a focus of biographies of Rasputin. It is the central theme of several recent examples, including Joseph Fuhrmann’s Rasputin: The Untold Story (2013) and Frances Welch’s entertaining Rasputin: A Short Life (2014), which includes discussion of the Soviet myth, a subject overlooked by Smith. Over recent decades, historians have analyzed in detail the political effects of the Rasputin myth and the broader influence of various rumors about “dark forces” at the court in uniting opposition to the monarchy across all classes of society. In a revolutionary crisis it is not the truth that counts but popular perceptions and beliefs. The stories of Rasputin became political realities.

But if Smith’s examination of these stories is not new, it is the most exhaustive, based on research in many archives and delivering the final word on every scrap of evidence in newspapers and memoirs. The result is a book that is overlong, overcrowded with names and details, serious and earnest (there are few jokes), but a valuable corrective to the more sensational and fanciful biographies available in English, such as the playwright-historian Edvard Radzinsky’s The Rasputin File (2000), translated from the Russian, and a stack of recent books in Russian that have regurgitated the old myths about Rasputin as a diabolic agent of the Jews or Freemasons bent on the destruction of Russia.

Advertisement

Hard facts about him are difficult to find. There are almost none for his first thirty years, a vacuum filled by all sorts of tales invented by Rasputin and others. For a long time even his age was the subject of mythology: Rasputin put it out that he was older than he was to support his image as a bearded “holy man.” In the Siberian village of Pokrovskoe, where he was born in 1869, the teenage boy was said to be a drunkard, lecher, and horse thief; they called him rasputnik, meaning “dissolute,” according to the stories that later circulated in the press. But Smith has uncovered more reliable evidence—in the local magistrate’s records that are part of the Tobolsk archives in Siberia—suggesting that Rasputin was no more than a rude, unruly boy, perhaps guilty of small thefts, but not of the more serious crime of stealing horses.

At some point, possibly in 1893, but more likely four years later, depending on which of his own versions of his life you believe, Rasputin left his village and joined the trail of stranniki, “holy wanderers or religious pilgrims” who for centuries had walked the length and breadth of Russia living off the alms of villagers. It is possible that he traveled as far as Mount Athos, the ancient center of Orthodox monasticism in northeastern Greece. Later he would boast of having walked to the Holy Land, although there is no record of this pilgrimage. “Rasputin developed through his travels a talent for reading people,” Smith argues, succumbing just a little to the mystifying spell of his own subject.

He could meet someone for the first time and strangely see inside them—what was on their minds, what troubles they had experienced in the past, who they were as people. And he knew how to talk to them.

Certainly he had a gift for healing, a way of touching bodies and relaxing minds that sometimes led to sexual abuse.

Rasputin lacked the education to become a priest (he was not a “mad monk”). His mixing of mysticism and eroticism had much in common with the practices of the khlysty (“the whips”), an outlawed sect that believed that sin was a necessary step to redemption. They danced naked and engaged in flagellation and group sex. In 1907, the Tobolsk authorities began an investigation into far-fetched allegations of Rasputin’s links to the khlysty. The investigation was stopped in 1908 and revived in 1912, but no incriminating evidence was found to connect him to the sect, Smith concludes from his reading of the files. Yet the story would not die. Five years later, following the February Revolution and the downfall of the monarchy, the Provisional Government launched a new inquiry but found nothing to indicate that Rasputin had been a khlyst.

In 1905 he appeared in St. Petersburg, at that time in the throes of strikes and demonstrations against the government that spread across the empire, threatening the monarchy. In the capital he attracted the attention of some of Russia’s leading clergymen, including the Archimandrite Feofan, Alexandra’s confessor, who introduced him to the imperial family. It was a time when the court and social circles of the capital were steeped in alternative forms of religion. There was a ferment of curiosity about spiritualism and theosophy, the occult and supernatural, hypnotism and faith-healing—a climate that “encouraged the belief that diabolic forces were at work,” Smith argues.

It was as a healer for their son, Tsarevich Alexis, that Rasputin drew close to the tsar and tsarina, although Smith is at pains to point out that “from the very beginning Rasputin did not shy away from addressing matters of state with the tsar.” No one can explain his strange ability to stop the boy’s internal bleeding (even once apparently by telegram), but each new “miracle” persuaded Alexandra that he was the answer to her prayers. Citing recent medical research, Smith asserts that the crucial factor was the calming impact of his words not just on Alexis but on his hysterical mother: “For decades the power of anxiety and negative emotions to worsen the effects of hemophilia, and, conversely, of relaxation and calm to decrease capillary blood flow and aid the healing process has been well known.” Possibly this was the explanation. But who knows?

Protected by the tsarina, Rasputin misbehaved. Tales of his debauchery in restaurants and brothels appeared in the tabloid press, which had a field day. The revolutionary threat had forced the tsar to concede new press freedoms along with political reforms in October 1905. As Smith shows, many of these stories were made up or inflated by the press, which did not let the facts get in the way of selling newspapers. As the damage from these scandals grew, the belief took root in some circles that Rasputin was the agent of “dark forces”—Jews, Freemasons, revolutionaries, etc.—who were using him to undermine the monarchy.

Advertisement

The police put him under surveillance and collected stories of his bribe-taking, drunkenness, and sexual exploits. Politicians called for his removal from the court. But Nicholas was having none of it. He saw Rasputin as “just a good, religious, simple-minded Russian,” the embodiment of the “sacred union” between the tsar and the Russian people—a medieval fantasy to which his beleaguered regime clung in the face of mounting pressure for political accountability. The fantasy was encouraged by Rasputin, who comforted Nicholas when he was plagued by doubts and reminded him of his coronation oath to rule as an autocrat: he did not, Rasputin told him, need to listen to his ministers or public opinion, but only God.

As Smith points out, the tsar saw his relations with Rasputin as private, for his family alone. The calming presence of the “holy man” was essential for his peace at home (“better ten Rasputins than one of the empress’s hysterical fits,” Nicholas explained to his prime minister, Pyotr Stolypin). The tsar could not understand why the government was unable to stop the newspapers from printing articles about Rasputin—as if the press freedoms he had granted meant nothing. When Stolypin urged newspaper editors to stop publishing stories, some reluctantly agreed to drop their interest in Rasputin, but others, Smith reports, said they would when “he disappeared and there was no more reason for the press to concern itself with him.” The police, meanwhile, collected copies of every article they could find on him in the Russian and the foreign press, but nothing more was done and the copies gathered dust in the archives. The situation was absurd. It underlined a growing problem for the monarchy that Smith does not discuss in depth: its inability to manage news and public information at a time when its survival depended on it.

The problem became more acute once Russia was at war with Germany. After a series of defeats, the tsar took command of the forces at the front, leaving the tsarina in St. Petersburg, where, encouraged by Rasputin, she took control of the government. Alexandra wrote to Nicholas with instructions on everything from food supplies to military strategies based on the advice of “our friend.” As the situation worsened, rumors spread that Rasputin and the tsarina were working for the enemy, communicating Russian troop maneuvers directly to Berlin. The German origins of the tsarina—she was daughter of the Grand Duke of Hesse—and the close connections between the Russian and the German courts gave credibility to these reports. As Smith rightly underlines, it was not just the soldiers and peasants who believed these wild rumors but officers, politicians, and French and British diplomats, enabling the Germans to sow even more confusion and discord by planting false news stories about secret talks between Berlin and tsarist ministers who were close to Rasputin for a separate peace. Such ideas would ultimately serve to justify the Revolution as a patriotic act.

Similar credence was given to the rumors of sexual scandals at the court. It was said that the tsarina was the mistress of Rasputin and the lesbian lover of Anna Vyrubova, her lady-in-waiting, who took part in orgies with them both. Alexandra’s “sexual corruption” became a kind of metaphor for the diseased condition of the monarchy—just as tales about the sex life of Marie Antoinette had eroded the authority of the “impotent” King Louis on the eve of the French Revolution in 1789. Who would want a cuckold for a tsar? Pornographic postcards conveyed this idea. One, for example, showed Rasputin holding Alexandra’s naked breast with the caption “Autocracy” (“samoderzhavie”)—a wordplay on the double meaning of the word derzhat (“to hold”) contained in “autocracy.” Rasputin’s sexual “hold” on the tsarina made him the true ruler of Russia.

None of these rumors had any basis in fact. (Vyrubova was a dim-witted spinster infatuated with the mystical powers of Rasputin and medically certified to be a virgin by a special commission appointed to investigate the charges against her in 1917.) But false as they were, the rumors were used to mobilize an angry public against the monarchy. Official efforts to counteract these tales were laughably weak. To propagandize their patriotic credentials the imperial family arranged a photo opportunity for the tsarina and her daughters dressed in Red Cross uniforms. They visited the wounded at military hospitals in Petrograd, as St. Petersburg had been renamed to make it sound less German at the beginning of the war. They did not realize that the image of the nurse had changed, not least because a consignment of nurses’ uniforms had fallen into the hands of the city’s prostitutes.

Smith does not discuss the failure of the monarchy to control its public image (or even recognize that it might have been a problem). But he describes well the revolutionary atmosphere created by the spread of these rumors in 1916. The mood is captured in a bawdy doggerel about Rasputin circulated by several Moscow newspapers in hectographic copies that Smith found in the archives:

A sailor tells a soldier:

Brother, no matter what you say

Russia is ruled by the cock today.

The cock appoints ministers,

The cock makes policy,

It confers archbishops,

And presents medals and positions.

The cock commands the troops,

It steers the ships.

Having sold our motherland to the Yids,

The cock has raised all the prices.

So the cock is mighty and powerful,

And rich with talents.

Clearly, this is no ordinary cock,

They say it’s fourteen inches long….

The final third of Smith’s biography deals with the plots to kill Rasputin (there was more than one) and the aftermath of his murder. The first conspiracy was initiated by the interior minister, Alexei Khvostov, a man distinguished only by the huge size of his belly and his extreme anti-Semitism, who was obsessed by the rumors of Rasputin as a German spy. His harebrained schemes to throw him from a train, poison him, and abduct and kill him in a car were all stalled by his underlings and revealed to Alexandra, who had him sacked.

The plot that ended in the murder of Rasputin is as much a hostage to mythology as every other aspect of this history. The standard account of his death, as roughly outlined at the start of this review, is derived from Yusupov’s memoirs, published first in 1927 as Rasputin and revised as Lost Splendor in 1953. But as Smith points out, “murderers make for problematic narrators,” and Yusupov particularly so. Having lost his immense fortune in the Revolution, when he had fled abroad, the one thing he had left to sell was “his notoriety as the man who killed Rasputin”: making money was “his primary motivation for writing the book,” which “had to be dramatic if it were to sell.” To justify the murder Yusupov presented it as the heroic vanquishing of the devil incarnate, which is how news of it was received by St. Petersburg society. But if the murder had been intended to save the monarchy by exorcizing the diabolic force corrupting it, the result was the opposite: it made the tsar ever more determined to resist reform. Alexandra thought the murder had been carried out by agents of the Freemasons.

Smith ends his book with the collapse of the Romanov regime in the February Revolution, which unleashed a vast new wave of propaganda and pornography depicting Rasputin as the personification of the “dark forces” from which Russia had been freed. It is a pity that Smith did no go on with his story beyond 1917. Rasputin enjoyed a long afterlife as a “demon” and a “saint” in the Revolution’s mythology. He was the antihero in many Soviet films, and was celebrated as “Russia’s greatest love machine” in “Rasputin,” the popular 1978 single by the West German group Boney M. Today his face appears on Russian beer and vodka bottles, on matrioshka dolls and other tourist objects, some of them for sale at the Yusupov Palace, where his murder has been recreated as a visitors’ attraction, with wax models in the basement room where he was shot.

As for his penis, a big part of the Rasputin myth, rumor had it that, apart from being fourteen inches long, his member had three warts strategically placed along its shaft that enhanced its potency. In 2009 a large penis floating in a jar of formaldehyde was the main exhibit at the newly opened Museum of Erotica in St. Petersburg. According to the museum, the grotesque object had been found detached from Rasputin’s body at the scene of his murder, sold to a group of Russian women emigrées, who had worshiped it as a relic, and was purchased by its director for $8,000 from an antiquarian dealer in Paris. But other facts cast doubt on its provenance. In 1914, Rasputin was examined after being stabbed in an earlier attempt on his life: according to the medical report, his genitals were so small and shriveled that the doctor doubted whether he was capable of the sexual act at all.