Nearly any anthology of classic eerie fiction—from the old Modern Library Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural to the compact New York Review Books paperback Shadows of Carcosa—will include Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows.” Sometime early in the last century, two men are canoeing down the Danube when they stop to camp on a small island thick with willow trees. From the first, the narrator feels uneasy, as if they were interlopers. In fact, they are. The pair have stumbled upon the threshold to some other dimension or realm of being utterly alien to ours. Once the campers are detected by the island’s hostile entities, escape becomes impossible—unless there is a sacrifice.

To many, including H.P. Lovecraft, “The Willows” is the finest story in the canon of supernatural fiction. Nonetheless, it contains no ghouls or slasher-movie gruesomeness, or any clanking apparitions back from that bourn from which no traveler generally returns. Instead Blackwood instills disquiet, then apprehension through a series of increasingly inexplicable details—a glimpse of what seems to be an otter, something unnerving about the swaying of the trees, a peculiar gong-like humming, the appearance of funnel-like hollows in the sand. The story avoids explicitness, but instead tantalizes, draws us in, and frightens us with something not quite said. Little wonder that Blackwood deeply admired the artistry of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw.

Blackwood himself is, arguably, the central figure in the British supernatural literature of the twentieth century. Vernon Lee (the penname of Violet Paget), Arthur Machen, and M.R. James all produced their best work as late Victorians. Lee’s Hauntings, highlighted by her seductive and unsettling “Amour Dure”—my own favorite ghost story—appeared in 1887; Machen’s major works, starting with The Great God Pan (1894), were products of fin-de-siècle London bohemia; and M.R. James’s Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, though published in 1904, comprised tales read aloud at Cambridge during Christmastime in the decade previous. James’s later collections maintain that same old-fashioned, port-and-stilton flavor.

All three of these writers are, in their differing ways, finer prose stylists than Blackwood—indeed, they rank among the finest in English—but none matches him in range, power, and sheer industry. Blackwood’s first magazine pieces, which began to appear in the early 1900s, launched a writing career that would eventually include some two hundred short stories and a dozen novels published over more than four decades. What’s more, he produced every kind of supernatural tale, from the sentimental to the horrific to the sacrilegious (in one, Jesus Christ appears at a dinner party), and of every length, whether the “ten-minute” short-short or the full-dress Edwardian bildungsroman. Blackwood’s most ambitious efforts, though, transcend the weird tale to become metaphysical fantasies. In them a deep affinity for nature or a heightened awareness of a surrounding spirit world brings his characters either rejuvenation or destruction. He is, all in all, an immensely interesting writer and now too little known.

Algernon Blackwood (1869–1951) grew up among the rich, landed, and aristocratic, the son of a high-ranking official at the Post Office. Fascinated by the natural world from an early age, the spiritually restless Blackwood dropped out of the University of Edinburgh to spend his twenties taking up odd jobs in Canada and the United States. As Mike Ashley tells us in Algernon Blackwood: An Extraordinary Life (2001), the future writer farmed, ran a hotel and bar, worked as a reporter for the New York Sun, and even modeled for the artists Charles Dana Gibson and Robert W. Chambers (the latter now mainly remembered for The King in Yellow, a volume of macabre stories about an accursed book of the same name; it is regularly alluded to in the hit television series True Detective). Blackwood only returned to London in 1899, after a decade in North America. By then already familiar with the mystical thought of Helena Blavatsky, he soon joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, the occult organization whose members included W.B. Yeats, Edith Nesbit, Aleister Crowley, and Arthur Machen.

Blackwood gradually drifted away from organized theosophy, but seems never to have wavered in his conviction that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in anybody’s philosophy. He drew on these beliefs, as well as his own experiences, when he began to publish collections of short stories in his mid-thirties, starting with The Empty House (1906) and The Listener (1907), but really finding his distinctive voice and themes in The Lost Valley (1910), Pan’s Garden (1912), and Incredible Adventures (1914).

As Julia Briggs writes in Night Visitors: The Rise and Fall of the English Ghost Story (1977), Blackwood “had a strong, almost Gnostic sense of the forces immanent in nature, which he dramatized in ghost stories set in the Canadian forests, the Swiss Alps, the Danube, Egypt and even the Caucasus.” Much of his genius was, in fact, a genius loci, his imagination being stimulated by specific places and especially by proximity to nature at its most wild and sublime. Throughout his life he canoed and camped regularly, spent months every year skiing in Switzerland, and traveled all over Europe and the Near East.

Advertisement

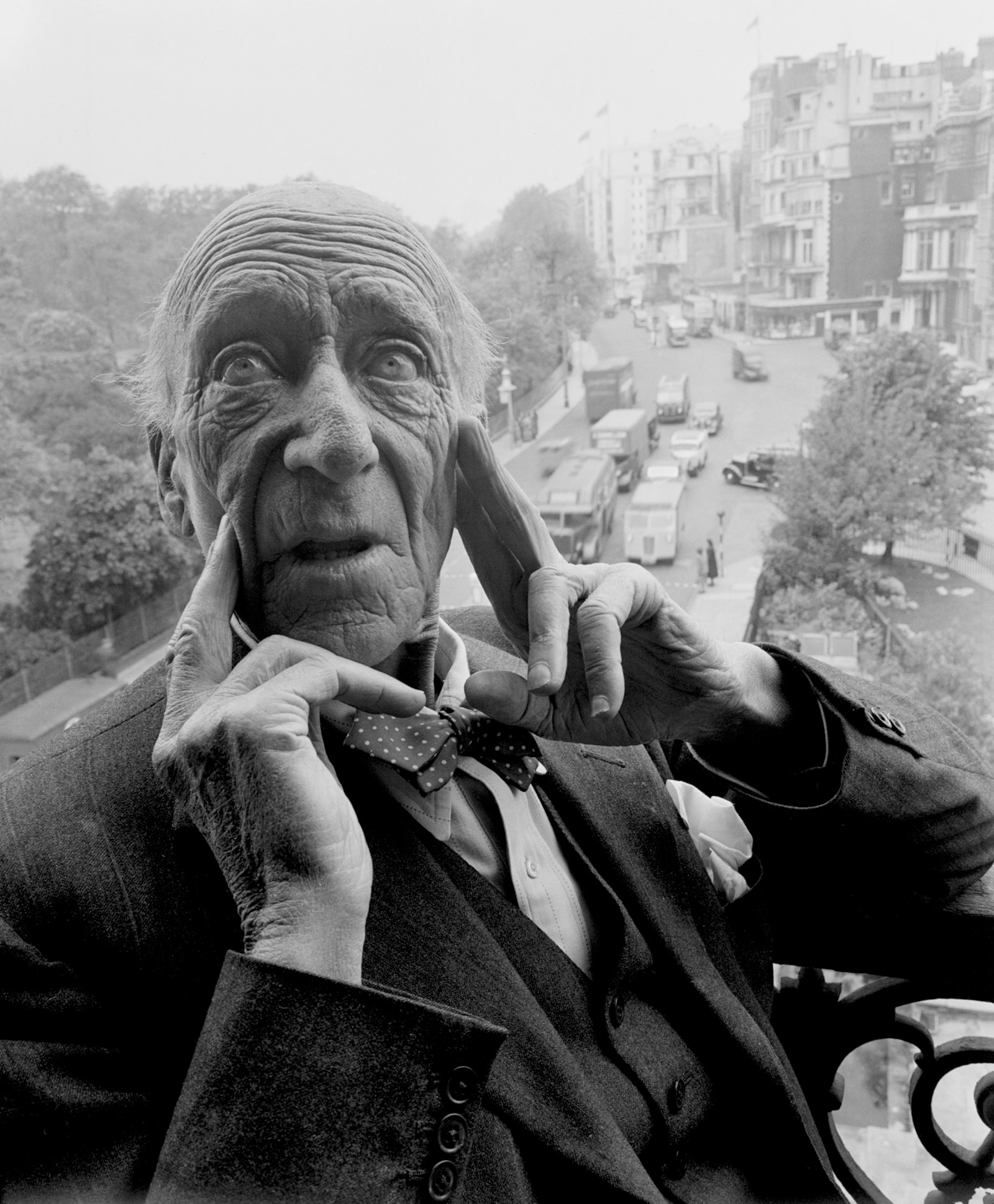

In the years just before World War I the tireless Blackwood produced several juvenile fantasies, one of which—the somewhat Peter Pannish A Prisoner in Fairyland (1913)—was adapted for the stage as The Starlight Express, with music by Edward Elgar. Once war broke out, he worked as an intelligence agent in Switzerland under the spymaster (and spy novelist) John Buchan. Afterward, during much of the 1920s, he concentrated on playwriting (largely unsuccessful), more stories for children, and a brilliant memoir of his youth called Episodes Before Thirty (1923). While continuing to write in the 1930s and 1940s, he acquired new popularity when he began to broadcast his shorter and more conventional stories on radio and television. His spectacularly weathered face—lined and darkened by the sun—and his personal charisma led audiences to call him “the Ghost Man.” He died in 1951 at age eighty-two.

Nearly all Blackwood’s strongest and most varied writing appeared in the decade between 1906 and 1916. More often than not, his short stories start with what seem to be, initially, trivial anomalies. A country manor is oddly, almost preternaturally warm. A comic writer finds his sketches growing sinister and grotesque. The new lodger in a rooming house, where the rent is surprisingly low, feels that someone is constantly listening. When at his best, however, Blackwood avoids the merely spooky or frightening and conveys an experience of the numinous and ineffable, often through a rushing, synesthesic prose.

For example, “The Wendigo,” another anthology standard, elicits not a feeling of horror but a mixture of awe and dread. Set deep in the Canadian forests, the doomed guide Défago “sees” the Wendigo, a wind-borne monster that is never described. Its presence is known only through certain smells, bizarre tracks in the snow, and, finally, a kind of “rapture” of the woods, signaled by Défago’s anguished cry just before he disappears: “Oh! Oh! My feet of fire! My burning feet of fire! Oh! Oh! This height and fiery speed!”

In general, though, Blackwood allows his leading characters to survive their ordeals and spectral temptations, as when the bewitched Hibbert of “The Glamour of the Snow” pursues a pale young girl high into the mountains—and is saved by luck and by church bells. But it is always a near thing. In “Ancient Sorceries” a middle-aged English tourist named Vezin is cautioned against stopping overnight in a small, picture-perfect French town “à cause du sommeil et à cause des chats”—because of sleep and because of the cats. But Vezin ignores the warning and, while he physically escapes, he never wholly recovers from the tug of the town’s beguiling diabolism. Throughout his writing Blackwood nearly always depicts the supernatural as balanced between the menacing and the deeply desired.

“Ancient Sorceries” itself is loosely framed as one of six paranormal investigations by the psychic detective John Silence. Whatever the background—ghostly invasion, devil-worship, a werewolf, the depredations of an ancient Egyptian mummy—Blackwood expertly builds up an atmosphere of the otherworldly coupled with the spiritually threatening. In “The Nemesis of Fire,” for instance, we are told about a groundskeeper troubled by an uncanny wilderness area on the estate: “No birds nested in the trees, or flew into their shade…. Animals avoided it, and more than once he had picked up dead creatures round the edges that bore no obvious signs of how they had met their death.” That’s the least unearthly aspect of these woods:

One of the gardeners whose cottage lies over that way declared he often saw moving lights in it at night, and luminous shapes like globes of fire over the tops of the trees, skimming and floating, and making a soft hissing sound…and another man saw shapes flitting in and out among the trees, things that were neither men nor animals, and all faintly luminous. No one ever pretended to see human forms—always queer, huge things they could not properly describe. Sometimes the whole wood was lit up, and one fellow…has a most circumstantial yarn about having seen great stars lying on the ground round the edge of the wood at regular intervals.

All these bizarre elements point to an occult explanation that only John Silence can perceive.

Silence himself ranks high among the more colorful rivals of Sherlock Holmes, though as “a man of power” he relies on shamanistic intuition as much as clever deduction. But while the traditional detective story, when confronted by “wrongness,” makes sense of the mystery and restores the world to its old familiar order, the supernatural tale discovers that “wrongness” is actually an unacknowledged aspect of a greater reality. At its end, if the writer succeeds, our consciousness is expanded, our understanding enlarged, our inner eyes opened. Some of Blackwood’s best stories even rise to phantasmagoric prose arias that read like accounts of acid trips.

Advertisement

Much of his fiction is clearly derived from the author’s own pantheistic experiences. This past spring Mike Ashley brought out The Face of the Earth and Other Imaginings, gathering hitherto uncollected material largely from Blackwood’s earlier years. Here one may read, for example, “ ’Mid the Haunts of the Moose” and “Down the Danube in a Canadian Canoe,” two memoirs of the camping trips that gave rise to “The Wendigo” and “The Willows.” The book also reprints “The Psychology of Places,” in which a woodsman friend, highly attuned to nature, tells the young Blackwood, “Never pitch your camp on the edge of anything.” You should, he instructs, “put the tent in the wood or out of it, but never on the borderland between the two.” Liminal places—thresholds, frontiers, entrances, gateways—stand on the line where opposing forces meet and they are never places of rest.

All of Blackwood’s writing presupposes—in Lovecraft’s words—“an unreal world constantly pressing upon ours.” Yet it also echoes the traditional alchemical mantra “As above, so below.” Blackwood forthrightly values what he called

signs and proofs of other powers that lie hidden in us all; the extension, in other words, of human faculty…. I believe it possible for our consciousness to change and grow, and that with this change we may become aware of a new universe.

He often sounds like a prophet of the Age of Aquarius.

Transformation, willed or not, is consequently Blackwood’s larger theme. In most of his tales of mystical awakening one finds, as he once wrote, “an average man who, either through a flash of terror or of beauty, becomes stimulated into extra-sensory experience.” Recreating that extrasensory experience emerges as the plot, almost the entire purpose, of his impassioned, breathless novellas, especially “The Man Whom the Trees Loved,” “Sand,” “The Regeneration of Lord Ernie,” and “A Descent into Egypt.” In them, characters surrender their souls to nature or to the allure of an ancient past, and the reader is left uncertain whether they have been wholly wrong to do so. Possessed by the elemental power of Natura naturans, they are drained of their humanity but, sometimes, left strangely exalted.

By contrast, in Blackwood’s most important novels his protagonists deliberately seek to master the universe, to become gods. The Human Chord (1910), The Centaur (1911), and Julius LeVallon (1916) must be among the most original works of fiction of the past century, though one must adjust to their leisurely pace, a certain metaphysical lyricism, and repeated philosophical divagations.

In The Human Chord, for instance, Blackwood depicts a former clergyman turned mystical adept who believes that “the universe, down to its smallest detail, sings through every second of time.” Sound, Philip Skale maintains, “was the primordial, creative energy. A sound can call a form into existence. Forms are the Sound-Figures of archetypal forces—the Word made Flesh.” Skale grows convinced that if he can properly intone the initial syllables of the hidden “true” name of God, he will bring about a radical transformation of himself and the world.

To create his apocalyptic chord, Skale requires four voices: he himself will sing the bass note, his housekeeper the alto, and a beautiful ward will provide the soprano. All he needs is the right tenor, and it takes him a while to find him. At first, the diminutive Robert Spinrobin is enthralled by Skale, who exhibits something of the grandeur and bulk of “Sunday” in Chesterton’s contemporary philosophical thriller, The Man Who Was Thursday. “My dear fellow,” shouts Skale,

at the Word of Power of a true man the nations would rush into war, or sink suddenly into eternal peace; the mountains be moved into the sea, and the dead arise. To know the sounds behind the manifestations of Nature, the names of mechanical as well as of psychical Forces, of Hebrew angels, as of Christian virtues, is to know Powers that you can call upon at will—and use!

Though professing benevolence, the overreaching Skale regularly skirts blasphemy, repeatedly asserting that the foursome will be metamorphosed, shedding their humanity to become as “gods.” All well and good for some, but Spinrobin and the ward Miriam have fallen in love. If they lose their humanity, will they also lose the love they feel for each other?

Early in The Human Chord, Skale declares:

Men, coarsening with the materialism of the ages, have grown thick and gross with the luxury of inventions and the diseases of modern life that develop intellect at the expense of soul. They have lost the old inner hearing of divine sound, and but one here and there can still catch the faint, far-off and ineffable music.

In Blackwood’s very next novel, The Centaur, he examines what happens to a man who suddenly hears that distant music.

While sailing to the Caucasus, Terence O’Malley, a freelance journalist, encounters a mysterious “Russian” who—like Philip Skale—seems curiously big, bulky, larger than life. It’s as though another, not quite visible shape emanated from his body and extended it. (For Blackwood, size matters: in “A Descent into Egypt,” the unfortunate Isley grows smaller, dwindling and lessening as pharaonic antiquity sucks out his very being, leaving him a human shell.) When O’Malley finally speaks to this huge but childlike stranger, the Russian’s first words are unsettling:

“Some of us…of ours…” he spoke very slowly, very brokenly, quarrying out the words with real labour, “…still survive…out there…. We…now go back. So very…few…remain…. And you—come with us…”

Stahl, the ship’s doctor, believes the supposed Russian is actually a cosmic being, a relict of the primordial Urwelt, in effect, “a little bit, a fragment, of the Soul of the World, and in that sense a survival—a survival of her youth.” That phrase “her youth” isn’t accidental. Inspired by the animistic thought of Gustav Fechner, both Stahl and O’Malley—like their creator—view the earth as “a conscious, sentient, living Being.”

Despite Stahl’s misgivings, O’Malley continues to spend time with the Russian. The gates, he feels, are opening. But to what? Perhaps a return to a lost paradise, a vanished Golden Age? Yet when the ship lands at Batoum, the Russian suddenly vanishes. Making his way inland, toward a region thought to be the cradle of the human race, the journalist hears whispers about pagan nature deities and picks up rumors of beings who come in the spring

and are very swift and roaring…. You must always hide. To see them is to die. But they cannot die; they are of the mountains. They are older, older than the stones. And the dogs will warn you, or the horses, or sometimes a great sudden wind.

O’Malley eventually undergoes, with dire consequences, an ecstatic vision of “the Great At-one-ment.” Are we to judge him afterward as truly enlightened? Or sadly deluded? Blackwood doesn’t say. However, the novel plainly critiques industrial society, largely by drawing on Fechner’s early formulation of the Gaia thesis, as well as Blackwood’s own pantheism, popular beliefs about astral bodies, and the latest discoveries in psychology, in particular those of William James. Indeed, James’s The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902), which sympathetically analyzes mystical states, the “oceanic” feeling, and spiritual awareness, could almost serve as an indirect commentary on much of Blackwood’s fiction. As O’Malley opines, “Men work like devils for things of no value in order to accumulate them in great ugly houses; always collecting and collecting, like mad children, possessions that they never really possess—things external to themselves, valueless and unreal.” In fact, what matters is “elsewhere and otherwise.”

That high-minded spiritualist doctrine animates Julius LeVallon, Blackwood’s novel about reincarnation. It opens when a middle-aged professor of geology named John Mason, on holiday in Switzerland, unexpectedly receives a letter:

FRIEND OF A MILLION YEARS,—Should you remember your promise, given to me at Edinburgh twenty years ago, I write to tell you that I am ready. Yours, especially in separation,

Julius LeVallon.

Ready for what? Mason recalls his first encounter—at least in this life—with his “friend of a million years.” LeVallon, a new boy at Mason’s school, had somehow recognized his fellow student and immediately asked a disconcerting question: “Have you then…quite…forgotten…everything?”

Through LeVallon’s promptings, Mason eventually starts to recall a sunbaked landscape, worship of the deities of wind and fire, and an esoteric ritual performed by three shadowy figures at a time when “the barrier between the human and the non-human, between Man and Nature, was not built.” Something, however, went awry during that ritual, something involving the “wrong use of an unconscious human body to evoke…particular Powers.” An imbalance was created in the universe that needs to be set right.

Two of those three original beings have now been reincarnated as Mason and LeVallon, or so the latter maintains. But where is the third? “She is now upon the earth with us,” says LeVallon. “I shall soon find her. We three shall inevitably be drawn together, for we are linked by indestructible ties. There is this debt we must repay—we three who first together incurred it.”

At school and later as an undergraduate at Edinburgh, Mason alternately believes and scoffs at his friend’s mumbo jumbo. But finally LeVallon locates the girl—a housemaid without beauty or education, whom he recognizes “at once”—and they marry. Mason expresses surprise

that a woman, so long ripened by the pursuit of spiritual, or at least exalted aims, should have returned to earth among the lowly. By rights, it seemed, she should have reincarnated among the great ones of the world.

“The humble,” Julius answers, “are the great ones,” adding that

an infallible sign of younger souls was their pursuit hot-foot of pleasure and sensation, of power, fame, ambition. The old souls leave all that aside; they have known its emptiness too often. Their hall-mark lies in spiritual discernment, the power to choose between the permanent and the transitory.

Most of the time the new Mrs. LeVallon remains unaware of her true self, though in dreams and trance states she radiates majesty and power. Mason begins to fall in love with her, partly because the two actually had been lovers, eons ago. LeVallon, by contrast, coolly regards his adoring wife as nothing more than the latest and quite temporary embodiment of an eternal soul.

When the time for the great instauration arrives, Blackwood pulls out all the stops, but once again, as in The Human Chord, the experiment ultimately fails. What’s worse, elemental powers are inadvertently diverted into the LeVallons’ unborn child. At the novel’s end, the now elderly Mason reveals that he has unsuccessfully tried to trace this cosmic orphan: “If alive he would be now about twenty years of age.” Those eager to learn more of that star-child would need to wait until 1921, when Blackwood brought out The Bright Messenger.

Joseph Conrad once memorably affirmed that the function of art was, above all, “to make you see.” Blackwood’s fiction goes even further: it hopes to make us “see through” the quotidian and materialist by undermining appearances, by enlarging our senses, by allowing us glimpses of a greater reality. That said, no one needs to believe any of this to appreciate Blackwood’s imaginative accomplishment. In attempting to express the inexpressible, his climactic scenes often rise to an ecstatic tumultuousness more than a little reminiscent, in verbal form, of Stravinsky’s exactly contemporary Rite of Spring. So, too, much of Blackwood could be summarized by the titles of the two sections of that ballet: “The Adoration of the Earth” and “The Sacrifice.”

Overall The Human Chord, The Centaur, and Julius LeVallon are as serious-minded and as intellectually thrilling as anything by Thomas Mann—and, at times, just as talky and long-winded. In his longer works Blackwood took large risks, and sometimes his philosophizing usurps his storytelling, or he repeats and overexplains his ideas. Happily, none of this is true of the terror stories where he shows himself a master of eerie atmosphere and narrative pacing. I envy anyone who has yet to discover “The Willows” or “The Wendigo,” “Keeping His Promise” or “Secret Worship.” Their ominous suspense is easy to enjoy and a good selection—for instance, E.F. Bleiler’s for Dover—can be read with pleasure. But if you would like to challenge yourself with truly unusual and demanding fiction, look for Blackwood’s powerful novellas, such as “Sand” and “A Descent into Egypt,” or one of his novels of cosmic mysticism. These remain, in every sense, revelations.