If you read every page of Tsering Woeser’s latest book and skip the first and last chapters of Tsering Topgyal’s, the ultimate message about the situation in Tibet is often the same. Chinese rule, writes Woeser, is no less than “ethnic oppression,” while Topgyal asserts that “the threat and use of coercive force to meet ideological, political and military objectives in Tibet have been enduring and well-documented features of Chinese rule from the beginning.” He recommends to Beijing that to secure a more placid atmosphere in Tibet, it should staff the region’s administration with Tibetan members of the Chinese Communist Party instead of the often brutal occupiers it now relies on.

Woeser came to Western attention with Voices from Tibet (2014), the collection of essays she wrote with her husband, Wang Lixiong.* She is the daughter of a teacher who became a senior officer in the Chinese army. After her birth in Lhasa in 1966 the family moved to Tibetan towns within China proper. At school she learned only Chinese, regarded as the language of a higher culture. After studying at a university in China she returned to Lhasa, where she worked for the Chinese Writers’ Group. There she wrote poems that were praised in China for their pride in Chinese culture, although, as Robert Barnett wrote in his introduction to Voices from Tibet, they also show “an engagement with Tibetan landscape, history and people.”

By 2004 her sympathies with the Dalai Lama were clear enough for her to be dismissed from her job in Lhasa and placed under strict surveillance in Beijing—although from her recent book we learn that she returns to Lhasa every year. Woeser’s is now the most eloquent voice defending the dissidents inside Tibet; equally she has, at much risk to herself, praised China’s only Nobel Peace Prize winner, the imprisoned Liu Xiaobo. Perhaps because of influential protectors in the Party’s hierarchy she has stayed out of prison.

Now she has written about a most dangerous subject, the attempted self-immolation of 146 Tibetans between February 2009 and July 2015. The men and women who subjected themselves to these agonizing ordeals throughout Tibet and in exile had called for Tibetan freedom and praised the Dalai Lama, who was later condemned by Beijing as the “criminal splittist” behind the burnings. Among the 125 who died were monks and nuns. Woeser recalls the deaths by self-immolation of seven Buddhist monks in South Vietnam in 1963 as acts of condemnation of the dictatorial rule of the Catholic president, Ngo Dinh Diem, who was chosen and supported by the US. About the photograph taken by the Associated Press’s Malcolm Browne of the monk Thich Quang Duc sitting enveloped in flames, John F. Kennedy said, “No news picture in history has generated so much emotion around the world as that one.” I have seen no similar pictures from Tibet, which may help to explain why self-immolations there have aroused little outrage in the West. The South Vietnamese burnings were associated with the American war. In the US and Europe, Chinese atrocities seem of less concern.

What set off the self-immolations in Tibet, according to Woeser, was the Chinese crackdown on monks and nuns in 2008, a few months before the Beijing summer Olympics, an event that China insisted must proceed without political protests. Several thousand monks, nuns, and laypeople demonstrated against the Chinese regime at a monastery associated with the Dalai Lama; the military police reacted violently, killing more than twenty people. The following year, the police blocked a prayer festival honoring the victims.

This led to the first self-immolation, by a monk. Woeser writes that the police fired their weapons at him as he was burning. Seven years later, it is not known what became of his body. Since that event, she writes, “I have documented every act of self-immolation and shared this information in my blog,” on which she provides updates on all dissident acts she has identified in China and Tibet. Because she visits Tibet every year, she can confirm that her information is accurate.

Of the 125 Tibetans who died, seventy-four were peasants or nomads. Woeser writes that one monk who burned himself to death in 2011 had doused himself with gasoline. When fellow monks took his dead body, as is customary in some Tibetan regions, for a “sky burial” on a mountainside, they were concerned that the vultures might not come so they cremated him instead.

Warren Smith, a historian of Tibet, in a letter to me, has added this helpful information:

Protests began in the center of Tibet culture and identity but quickly spread to the old traditional frontier between Tibet and China (which the Chinese imagine should be more assimilated by this time)…. The further protests by means of self-immolation have continued there as opposed to little at all in Lhasa and most of the TAR [Tibet Autonomous Region].

The resentment of the Tibetans against the Chinese, according to Woeser, was based on the sense that their traditional identity had been violated, a conviction that reaches back to 1934 and 1935, during the Long March, when Mao’s forces, fleeing the pursuing forces of Chiang Kai-shek, passed through a predominantly Tibetan region inside China. This retreat has always been hailed as heroic, beginning with Red Star Over China (1937) by Edgar Snow, who heard Mao’s version of what happened at his guerrilla refuge. But, Woeser contends, the Reds looted food from the monasteries and massacred monks and laypeople. (This account is new to me.)

Advertisement

Since 1950, when the Communists invaded Tibet, Woeser writes, they have attempted to destroy the central elements of Tibetan culture. Religion has been suppressed. During my visits between 1981 and 1989, some temples and monasteries were barely functioning and they were closely observed, including by policemen dressed as monks. I saw Chinese tourists and soldiers walking the wrong way around religious sites, a deliberate affront. The great temple complex at Ganden had been razed almost completely. In 1995 the Chinese kidnapped the infant Panchen Lama, the second most important figure in Tibetan Buddhism, who had been recognized by the Dalai Lama. What happened to him remains unknown. The Chinese authorities put their own “incarnation” in his place.

Woeser describes how Tibet’s ecosystem has been badly damaged as nomads and their flocks have been moved from the regions in which they lived and Hans—ethnic Chinese—have taken their place, mining copper, silver, and gold, and polluting the rivers. Chinese has become the main language in schools and Tibetan has been reduced to the status of a second language, if it is taught at all. Large numbers of Hans have entered Tibet, whether to farm or do business. In Lhasa they outnumber Tibetans. The pervasive surveillance system, she writes, has caused widespread fear throughout Tibet.

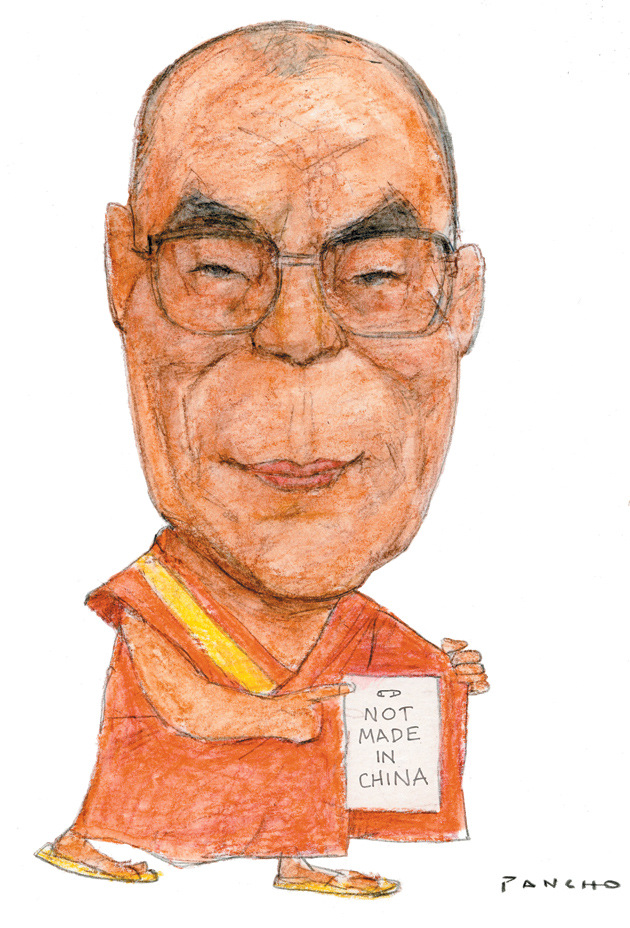

Woeser takes up the question of why the Dalai Lama has not spoken out against the self-immolations. He has said often that while he neither encourages nor condemns them, he feels deeply for their families and prefers not to comment, but he has been seen to weep when the self-immolators’ names are read out. Woeser considers the self-immolations a “non-violent resistance” against ethnic and environmental oppression. What the occupiers must have noticed, but never acknowledged, is that after many self-immolations local people brought their traditional swords and rifles to monasteries to indicate that they did not intend attacks on the Chinese.

News about self-immolations has been blacked out on the Chinese Internet, while official statements insist that the self-immolators are either insane, selfish, failures, or criminal. Woeser’s own judgement is:

Because no other method is available for Tibetans to voice their protests, and because only the horror of self-immolation is able to capture the attention of the world, it has become the choice of the bravest protestors in Tibet. And in the past few years, such individual acts of bravery and sacrifice have gradually grown into a broad protest movement that continues to this day.

In her previous collection of essays, with some irony as well as passion, Woeser observed:

Perhaps we should thank our authoritarian government for its devious way to publicize Tibetan tradition and history. Thanks to Beijing’s efforts to snuff out our cultural practices, ever more Tibetans, especially the younger generation, are taking them to heart.

Tsering Topgyal, a lecturer in international relations at the University of Birmingham, was sent out of Tibet as a child by his family, schooled in India, and after coming to the UK received a Ph.D. at the London School of Economics. It was there, I suppose, that he learned the particular jargon of his branch of political science. I give only one example:

One of the key features of the reconceptualized insecurity dilemma is the relevance of transnational and international forces. Because of Tibetan advocacy and normative, ideological and geopolitical reasons beyond the Tibet issue, the conflict has acquired transnational and international dimensions.

Topgyal also writes, somewhat more clearly:

The Tibetans and the Chinese have been locked in a conflict in which both sides have used violence, subtler hearts-and-minds approaches and dialogue and diplomacy…. This is in spite of the fact that in the post-Mao era, constituencies for a negotiated settlement have existed on both sides…during the lifetime of the current Dalai Lama.

He believes that more by way of mutual goodwill is needed.

Topgyal criticizes the “extant literature” on the relations of China and Tibet because it ignores what he calls “Tibetan diplomatic positions,” both inside and outside Tibet, including Tibetan openness to coexistence with China. Still, when he considers the dismal realities of the land of his birth, he draws on that literature, including familiar sources from scholars and historians such as Woeser, Tsering Shakya, Warren Smith, Robert Barnett, and Melvyn Goldstein. He quotes Smith on China’s ultimate goal: “to transform Tibetan national identity into Chinese identity, to eradicate Tibetans’ loyalty to the Dalai Lama, and to cultivate Tibetans’ loyalty to China instead.” In passages like this, Topgyal largely abandons academic language to make a fairly clear judgment:

Advertisement

The centrality of language and Buddhism in Tibetan national identity, which sits uncomfortably with both Beijing’s security and state-led nationalism and the popular Han-supremacist nationalism, invites the hostility of regional and central authorities as well as most common Chinese.

In fact Topgyal, in much of his book, emphasizes two major realities: the Tibetans’ sense of national and cultural identity, and China’s rulers’ intrusions into Tibet over many centuries. He acknowledges that during the thirteenth century, at the time of the Mongol conquest of China, Tibet was a vassal state allowed to govern itself, contrary to Beijing’s later insistence that Tibet has always been part of China. Similar relations of mutual respect characterized the first half of the Manchu dynasty until the end of the eighteenth century, when the non-Han Manchu rulers showed Tibetans “reverence, patronage and protection” and shielded Tibet from external dangers.

This relationship was wrecked, Topgyal shows, by the Chinese policies of “assimilation” that have been more and more harshly imposed since the imposition of Communist rule in 1950, and especially in the period after 1989. He describes the concerns that cause the Chinese to feel insecure: “sovereignty, territorial integrity, legitimacy, organizing ideology, the Leninist political system and state institutions, national identity, and image and regime survival.” His list of Chinese depredations is considerable: they include financial subsidies concentrated largely on the security apparatus and large-scale projects of use primarily to the rapidly increasing Han population, such as higher wages for Chinese workers and investments in contracts for Chinese construction companies that, he says, eventually bring profit to enterprises in China. In addition to the “cultural revolution-style destruction there are attempts at ‘mission civilisatrice,’” the phrase used by the ninteenth-century French to justify their conquest of Indochina.

The Han influx, Topgyal observes, reminds Tibetans “of the vulnerability of their identity,” including shop signs primarily in Chinese and parts of Lhasa leveled to be replaced by Chinese-style buildings, whose “ugly construction,” as he quotes Woeser, resembles those in Chinese cities; and he cites her dislike of the way Lhasa is hung with Chinese lanterns during the Tibetan New Year.

Noting some signs of “liberalization” regarding Tibetan Buddhism, Topgyal cautions that these are “purely strategic,” in view of the Chinese hope that superstition will “quietly wither away.” In any event, this “liberalization” is contradicted by Beijing’s Order No. 5, in force since 2007, “essentially prohibiting Tibetan lamas from reincarnating without prior approval from the Chinese government.” This stricture must astound Tibetans who believe that reincarnating is wholly beyond the control of the mortals who may reincarnate in their next life—not necessarily as a human being. Topgyal also makes clear that the Tibetan language has been downgraded in favor of Chinese.

As a startling example of how official policy is not working, Topgyal claims that many Chinese are secret believers in religion. I don’t doubt this. But he quotes a somewhat unconvincing account from Lodi Gyari, the special envoy to the Dalai Lama, saying that ex-Premier and Party General Secretary Zhao Ziyang, on his deathbed in 2005 after sixteen years of house arrest, requested that the Dalai Lama “conduct Buddhist rituals for him.”

Topgyal rather gingerly touches on self-immolations, giving information that partly overlaps with Woeser’s, including who the self-immolators were and where they were from. He notes that the acts were responses not only to “brutal security and surveillance operations” in 2008, to which he says the Tibetan response was nonviolent, but to “the discursive content” of official propaganda, leaving us to imagine what that may be.

Finally, Topgyal suggests a way out of the mutual “security dilemma” for both Chinese and Tibetans. It would “address most of the fears on both sides.” Tibet should be granted internal autonomy—as has long been advocated by the Dalai Lama. But—many will regard this as fatal to his hopes—any solution that casts doubt “on Chinese sovereignty over Tibet and the CPP’s primacy in Tibet will fall by the wayside.” Tibetan Communist Party members, he further suggests, must be involved in local administration. This suggestion, as Topgyal does not say, also seems very likely to fail to be accepted by the Party; such Tibetans would have to have acknowledged China’s fundamental contempt for Tibetan culture, not to mention for the Dalai Lama. As matters stand, neither Topgyal nor anyone else will find Tibetan Party members who can truly reconcile Beijing’s interests with those of the Tibetan people.

The Dalai Lama has told numbers of people, including me, that his American medical advisers give him another twenty years of life, taking him past his one-hundredth birthday. This would be, as he has said, “the Chinese nightmare.” How is this nightmare to be dealt with? Here Topgyal’s work divides into two parts. He apparently wants to ensure his standing as an up-to-the-minute political scientist, while also looking forward to his forthcoming book, which will be based, he writes in academic prose, on concepts of “securitization and ontological security to deconstruct the security rationale at the heart of China’s policy towards the Tibetans.”

In fact, Topgyal’s account of what actually has happened in Tibet since 1950 describes a horrific tragedy in which the oppressor’s and the victim’s interests cannot be reconciled. This account shows where Tsering Topgyal’s heart unmistakably lies.

-

*

See my review in these pages, July 10, 2014. ↩