The Chinese were gloating over the flaws of the American political system long before the election of Donald J. Trump. Coming from an obsessively orderly system, they were again and again baffled by an institutional setup that flips control from party to party every four or eight years, bestows supreme power on novices like a former one-term governor who owned a baseball team and a one-term senator with prior experience in a state legislature, and allows each new ruling group to undo the policies of its predecessor.

In a 2013 cartoon, Chinese propagandists contrasted Barack Obama’s rise with Xi Jinping’s thirty-year progression up the bureaucratic ladder.1 The Chinese system passes its leaders through “decades of selections and tests,” the video says, with just a one in 140,000 chance of promotion even to the minister level, much less to the top grade of “state leader.” “This is one of the secrets of the ‘China Miracle.’”2

In Chinese Politics in the Xi Jinping Era, Cheng Li of the Brookings Institution, our leading expert on the Chinese political elite, describes the career paths followed by Chinese officials with great sophistication. He has been studying this group for decades, tracing the backgrounds of successive Central Committees, whose four hundred or so members and alternates meet once (occasionally twice) a year to approve major policy documents, and are newly elected every five years to approve automatically elections to the two most powerful organs of government: the Political Bureau, usually twenty-plus members, and its Standing Committee, usually five to nine members.

Li shows that there are now several versions of the Chinese path to the top. The most common channels involve advancement through the Party, government, or military bureaucracies. Others include service in the country’s court and procuratorial hierarchies or success in business management either in China’s giant state-owned enterprises or in private firms.

Comparing the 12th Central Committee (1982) and the 18th Central Committee (2012), Li shows that the political elite is more educated than before (99.2 percent have college degrees compared to 55.4 percent in 1982), more technocratic (21.5 percent have technical backgrounds versus 1.9 percent, although this is down from 51.8 percent in 1997), and includes more legal professionals and businessmen. As he did in a previous book, China’s Leaders: The New Generation (2001), Li argues that such shifts in the makeup of the elite will drive changes in policy. But in view of the ways that elites are formed by choices at the top, the Party is more likely to shape the elite than the elite to shape the Party. For those who make it this close to the top, their primary loyalty is to the regime rather than to the institutions or professions in which they took part.

China’s fairly recent ability to renew and upgrade its political leadership over the course of several decades is unique among authoritarian systems. Under Mao, in the Soviet Union under Brezhnev, in Mugabe’s Zimbabwe, and in similar systems elsewhere, leaders clung to power for decades while their regimes stagnated or fell into disorder. Li shows how formal rules and informal norms put in place by Deng Xiaoping and his successor, Jiang Zemin, have promoted the turnover of elites in post-Mao China.

With rare exceptions, officials have to move up or out after a maximum of fifteen years at a given rank. Unless granted special dispensation, they must retire from government and Party posts at a fixed age between fifty-five and seventy-two depending on their rank. (Indeed, experts have shown that the rules for length of service in grade and age of retirement at rank are so tough that it would be impossible to reach the top leadership at an age young enough to be eligible to serve there, except for special paths upward that are built into the system for unusually talented cadres.3)

For the top positions, incumbents are limited to two five-year terms. An official normally does not hold a top position in the province in which he or she was born. Each provincial-level administration has two seats in the Central Committee, certain provinces are normally represented in the Politburo, and the military has two seats there.

The principle of collective leadership dictates that the members of the immensely powerful Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) make policies in different domains by chairing various “leading small groups” (lingdao xiaozu) dealing with different fields of policy—for example, foreign affairs, national security, and financial and economic affairs. The PBSC meets once a week and the full Politburo once a month to pass on the major decisions taken by these leading groups.

Li argues that these rules have generated a system of “bipartisanship” in which rival factional groupings “check and balance” one another. He gives the example of the informal norm that a candidate for the PBSC must first serve one term in the Politburo and still be under the age of sixty-eight when the time comes for the leadership to turn over. He predicts that this rule will force Xi Jinping, who has been consolidating a great deal of personal power, to staff a majority of the next Politburo with members of a rival group that Li labels the Chinese Youth League faction (tuanpai), thereby maintaining the factional power balance and avoiding a destabilizing power struggle.

Advertisement

This claim that there are two clearly differentiated factions or camps—which Li refers to variously as the “Jiang (Zemin)-Xi (Jinping) camp,” also known as the “elitist coalition,” and the “Hu (Jintao)-Li (Keqiang) camp,” also called the “Youth League faction” and “populist coalition”—is open to doubt, giving too much weight to a number of facts. It is true that the last stages of Xi Jinping’s rise to power took place when Jiang Zemin was China’s leader, and just after Jiang’s retirement when he still retained influence. But Jiang should not be called Xi’s “main patron,” since Xi’s rise was endorsed by all the members of the collective leadership.

It is also true that many of Xi’s staff and supporters, like Xi, are called princelings since their fathers were Party leaders under Mao. But as Li acknowledges, the princeling group has no political coherence. It is true that Premier Li Keqiang spent much of his career as an official of the Communist Youth League, as did former leader Hu Jintao, and that neither is a princeling. But the Youth League has 90 million members and is too large an organization for even its leading cadres to serve as a resource for a single faction. It is instead, as shown in a recent dissertation by French political scientist Jérôme Doyon, a testing ground and reservoir for the Party’s personnel office, called the Organization Department, which uses it to train political generalists and provide accelerated promotions to promising cadres so they can reach higher ranks at an age young enough to serve in them.4

Indeed, as Li points out, some of Xi’s closest followers, like Director of the CCP General Office Li Zhanshu, are former high officials of the Youth League. It is true that the princelings form an elite—partly political, partly entrepreneurial—while the Hu Jintao leadership in the past and Li Keqiang today have promoted policies aimed at reducing rural poverty and developing a social welfare system. But these policies reflected a consensus in the leadership rather than a partisan position.

Li is right, however, along with other analysts like David Shambaugh,5 to point out that Xi is challenging the fragile norms of the system by arrogating so much power to himself. He has violated the principle of collective leadership by taking control of most of the leading small groups—such as those on foreign affairs, domestic security, finance and economics, and promoting reform—and by creating a personality cult around himself under which he has been designated as the “core” of leadership.6 His anticorruption campaign has destroyed the networks of rivals like Bo Xilai, the former high-flying Party secretary of Chongqing, and Zhou Yongkang, the former security chief. Li believes he is also undermining Li Yuanchao, although the claim is controversial since Li still serves in the ceremonial post of vice-president.

At the 19th Party Congress in the fall of 2017, many expect Xi to give his anti-corruption czar, Wang Qishan, a second term on the Standing Committee, which would break the rule that PBSC members sixty-eight or older should not be reelected. Many experts also expect that Xi will not appoint an heir apparent, which would lay the groundwork for him to serve a third or even more terms as general secretary, in violation of both the age rule and the two-term norm. Indeed, Li worries that Xi might break all the rules next year and “pick—at his will—members of the [PBSC] who will serve largely as his personal cabinet.”

Li does not explore why Xi is doing this. In China’s Crony Capitalism, Minxin Pei, a professor at Claremont McKenna, offers a possible answer: to fight a process of regime decay that has arisen from what Pei in a previous book called China’s “trapped transition.”7 He believes the problem started in the early 1990s, when Deng Xiaoping relaunched economic reforms after the setback at Tiananmen Square. At that point, after the first decade of reform, the state owned all the country’s land, utilities, and large mines and enterprises. Deng and his successors wanted to transfer more of the economy to private management in order to achieve greater efficiency and faster growth, but without weakening the regime’s political control. Therefore, “instead of complete privatization, the government sought to disentangle control rights from ownership,” ceding only “use rights” to private entrepreneurs and keeping ultimate control to itself.

Advertisement

This process of “incomplete reform” interacted pathologically with other reforms that were put in place at the same time: decentralization of control over many state assets to lower levels of government; “one-level-down” personnel management that gave Party leaders at each level the authority to appoint cadres at the level below them; and the attempt to rationalize the career system by giving cadres at each level hard performance targets, especially for economic growth. It became not only possible and attractive, but indeed almost necessary, for ambitious local officials to collude with one another and with their relatives and friends to increase the productivity of dormant state assets. It hardly seemed out of line to accept gifts from a variety of sources when one’s associates were using state assets to generate wealth for themselves and the community.

This “crony capitalism,” as Pei calls it, produced some spectacular abuses. In 2014 the South China Morning Post reported that a retired Politburo member and head of military personnel, Xu Caihou, had accumulated in his basement “more than a tonne of US dollars, euros, and yuan.” It took ten trucks to cart off his illicitly acquired jade, antiques, and other valuables.8 After the arrest of security chief Zhou Yongkang, photographs appeared online purporting to show rooms in his house with entire walls made of gigantic carved jade tableaux and major items of furniture comprised of tanks of rare live fish.9 The brilliant reporting of Michael Forsythe and David Barboza for Bloomberg and The New York Times revealed megamillions made by relatives of top officials, including Deng Xiaoping’s grandson-in-law, the wife of former premier Wen Jiabao, and Xi Jinping’s elder sister. All this brought to light the selectivity of the anticorruption campaign.10

But these cases were extreme. To understand the more typical cases that permeate the bureaucracy from top to bottom, Pei compiled 260 reports of officials and others who were caught and whose crimes were detailed in official media, presumably to warn the rest of the bureaucracy and assure the public that corruption was being attacked. Pei uses the economistic language of buyer, seller, market, value, and risk to uncover the structures of corrupt deals and assess the prices of different types of assets at different administrative levels.

Pei does not believe that Xi’s anti-corruption campaign can reverse the regime’s political decay. After a quarter-century of looting of state property, he points out, the state still owns 51 percent of the country’s total net worth, and the value of these assets has even gone up as the economy has boomed. The incentives to corruption are degrading the regime’s morale, its legitimacy, and its governance performance, and are sparking more intense power struggles. Cheng Li holds out hope that Xi Jinping might slightly reverse the hyperconcentration of power by allowing the Central Committee at the 19th Congress to elect Politburo members from a limited slate of candidates, a new procedure since the slate has always been selected by the outgoing Politburo. But Pei judges that “the possibility of remediation through the democratic process simply does not exist in China.”

Pei may exaggerate the degree to which corruption threatens the survival of the regime. For one thing, China is not bedeviled like Tunisia and Egypt by the kind of petty corruption that set off the Arab Spring. The collusive corruption Pei describes enrages ordinary citizens only when it comes to light accidentally (as in the scandal that broke when Internet users noticed in online photos the many expensive watches worn by a provincial official11), or when the regime chooses to reveal corruption in the controlled press to serve its propaganda purposes. It is important to realize that corruption hurts people whose land is seized; and it hurts miners who work in unsafe mines as well as victims of pollution and consumers who buy unsafe products. But corruption also helps entrepreneurs protect insecure property rights, cut through bureaucratic red tape, and generate growth,12 which in turn may improve support for the regime, or at least toleration among the growing middle class. Thirdly, although Pei believes that the anticorruption Discipline Inspection Commission is institutionally weak, many observers claim it is changing the bureaucracy’s culture.

To be sure, conventional wisdom holds that only liberal institutions like an independent judiciary and a free press can control corruption, as Martin Wolf suggested in a December 13 article in the Financial Times.13 But authoritarian and even partially politicized anticorruption institutions can also have an impact. In Double Paradox: Rapid Growth and Rising Corruption in China, Georgia State University scholar Andrew Wedemann showed that China’s anticorruption efforts from 1992 to 2006 had at a minimum “prevented corruption from spiraling out of control.” Xi’s anticorruption campaign has been much tougher than previous efforts. A close observer writing under the pseudonym James Leung in Foreign Affairs asserts that it has a real chance to “produce a cleaner and more effective form of authoritarianism.”14

Moreover, the Chinese economy would not be as strong as it is if crony capitalism were the only kind of entrepreneurial activity. Some of China’s largest and most successful firms are authentically private, like the digital commerce giant Alibaba, the Internet service portal Tencent, and the Web services provider Baidu. Not coincidentally, these companies belong to the digital economy, whose explosive growth was no more anticipated in China than it was elsewhere. They grew with foreign capital and innovative technology, not as a result of either government policy or powerful connections. If they have offended the authorities, this has not been reported.15 But so far as we know, their businesses do not depend on corrupt access to power.

A theme that links the two books is Xi Jinping’s battle with the bureaucracy. At the Third Plenum of the 18th Party Congress in 2013, Xi announced a bold reform plan, known as the “Sixty Points,” that called for “letting the market play the decisive role in allocating resources.” This meant that the government would no longer allocate assets as it had done before, but would force enterprises to scramble for capital and other resources in a competitive environment while the government would retreat to the responsibilities of macroeconomic manager and market regulator.16 The same plenum also announced decisions to step up social control and enforce ideological conformity. The repressive part of Xi’s program has moved forward. Among other things, the regime sentenced Uyghur intellectual Ilham Tohti to life in prison; punished the families and even the communities of Tibetans who immolated themselves in protest of government policies; tore down crosses from the roofs of Christian churches in Zhejiang province; detained leading civil rights lawyers on charges of subversion of state power; and harassed and surveilled leading women’s rights activists.

But little progress has been made in economic liberalization. The reason for this is the diffuse character of authority in the Chinese bureaucracy, which enables institutions targeted for reform to resist and delay. China presents an odd combination of centralized and delegated power. The leaders can set any policy they like, but implementation depends on the Party secretaries in each agency and at each level who are vested with nearly absolute power to figure out how to apply the policy in the units they control.

Each Party secretary is under tremendous pressure to perform, and to do so within a maximum of two terms in office, often less. But the instructions on what to do are vague. The Sixty Points, for example, call for cadres to

unswervingly consolidate and develop the public economy, persist in the dominant position of public ownership, give full play to the leading role of the state-owned sector, and continuously increase its vitality, controlling force and influence.

But the cadres are also to “unwaveringly encourage, support and guide the development of the non-public sector, and stimulate its dynamism and creativity.”

This way of articulating policy is a legacy of the Chinese Communist Party’s rise to power as a movement of scattered guerrilla bands operating across China’s vast landscape without modern communications. In his 1966 classic, Ideology and Organization in Communist China, Franz Schurmann pointed out that the Communist movement used ideology as “a system of communication,” relying on “standardized categories and language” to “transmit their policy commands to every corner of the country.”17 Local forces would interpret the broad “spirit” of central commands and apply them to local circumstances.

Officials continue to do something similar today because the country remains vast and conditions diverse, and because the legal system, whose construction was started in earnest only in 1979, remains underdeveloped. Indeed, the administrative reforms of the 1980s and 1990s described by both Li and Pei, which were intended to enhance the agility and creativity of the bureaucracy, intensified the decentralized character of Chinese administration. This sometimes produced examples of daring local reforms18 but more often provided what Pei calls “the soil of crony capitalism,” and perhaps more often still, generated immobilism, when officials feared to take responsibility for decisions they were not sure would later be judged as correct.

Unable to remake the bureaucracy overnight, Xi is pushing it with the forces he has available—among them the anticorruption campaign and an ideological crackdown.19 His strongest tool is the ability to empower people he trusts. Even before the 19th Party Congress, Xi has promoted numerous provincial Party secretaries and governors who did not fulfill the usual prerequisite of serving as a full or alternate member of the Central Committee. He has called an official out of semiretirement to serve as governor of a major province.20 He jumped an official two levels, from chair of the discipline inspection commission in one province to governor of another.21

These provincial appointments are more important to him than PBSC appointments. In deciding policies at the central government level, members of his personal staff like Liu He (economics) and Li Zhanshu (political affairs) often exercise more authority than the officials nominally in charge of the relevant issues. It is in the provinces—each the size of a large country—that Xi needs to implement his policies. One should therefore not expect a balance among factions when central-level appointments are revealed at the 19th Party Congress, but the increasing irrelevance of factional considerations as Xi continues to employ the people he thinks he can count on in both the center and the provinces.

Xi’s challenges will intensify with the advent of Donald Trump. The Chinese were not surprised by his victory in the election but they hoped that his deal-maker side would shape his approach to China. Instead, so far, the disruptor side has come to the fore. By accepting a congratulatory phone call from Taiwanese president Tsai Ying-wen and referring to her as “the President of Taiwan,” Trump challenged the long-standing American one-China policy that has helped to maintain stability in US–China–Taiwan relations for four and a half decades, although it is unclear whether he plans to carry the challenge beyond the level of protocol. By appointing Peter Navarro, the author of the anti–free trade polemic Death by China, as head of a to-be-created White House National Trade Council, he signaled an intention to fend off Chinese imports with new tariffs. He struck a tough tone on the South China Sea by referring to China’s fortified manmade islands in a tweet as a “military fortress the likes of which perhaps the world has not seen.” Xi can still hope that Trump will be distracted by worse problems elsewhere and willing to make bargains with a fellow strongman. But he must be prepared to retaliate blow for blow if the new president takes steps Xi believes harm Chinese interests.

Officials around Xi have lately taken an interest in Francis Fukuyama’s two-volume study of political order and political decay.22 In the first volume, Fukuyama argues that the Chinese built “the first modern state” as far back as the third century BC; in the second, he argues that contemporary China has rebuilt this highly capable state. Many in China have interpreted his ideas as confirming the benefits of authoritarian rule. In 2015, Fukuyama had separate discussions with Xi Jinping and Wang Qishan about, among other topics, how to combat corruption.

But in a recent essay Fukuyama reminds Chinese readers that his theory is not only about the strong state but about its relationship with two other sets of institutions—those that provide rule of law and those that provide political accountability. A “legitimate and well-functioning political system,” Fukuyama writes, “needs to have all three pillars in place, operating in proper balance.” The Chinese system as it is structured today “is unbalanced, with insufficient constraints on executive power,” and vulnerable to what he calls the “bad emperor” problem, the risk that an all-powerful ruler will use power for bad ends.23

This is the same worry expressed by Li and Pei. If democracy has an advantage over authoritarianism, it is that the struggles of interest, power, and ego that are the unavoidable stuff of human life take place in the open. The attempt to repress them runs the risk that they will break out sooner or later, and that kind of upheaval can be hugely destructive.

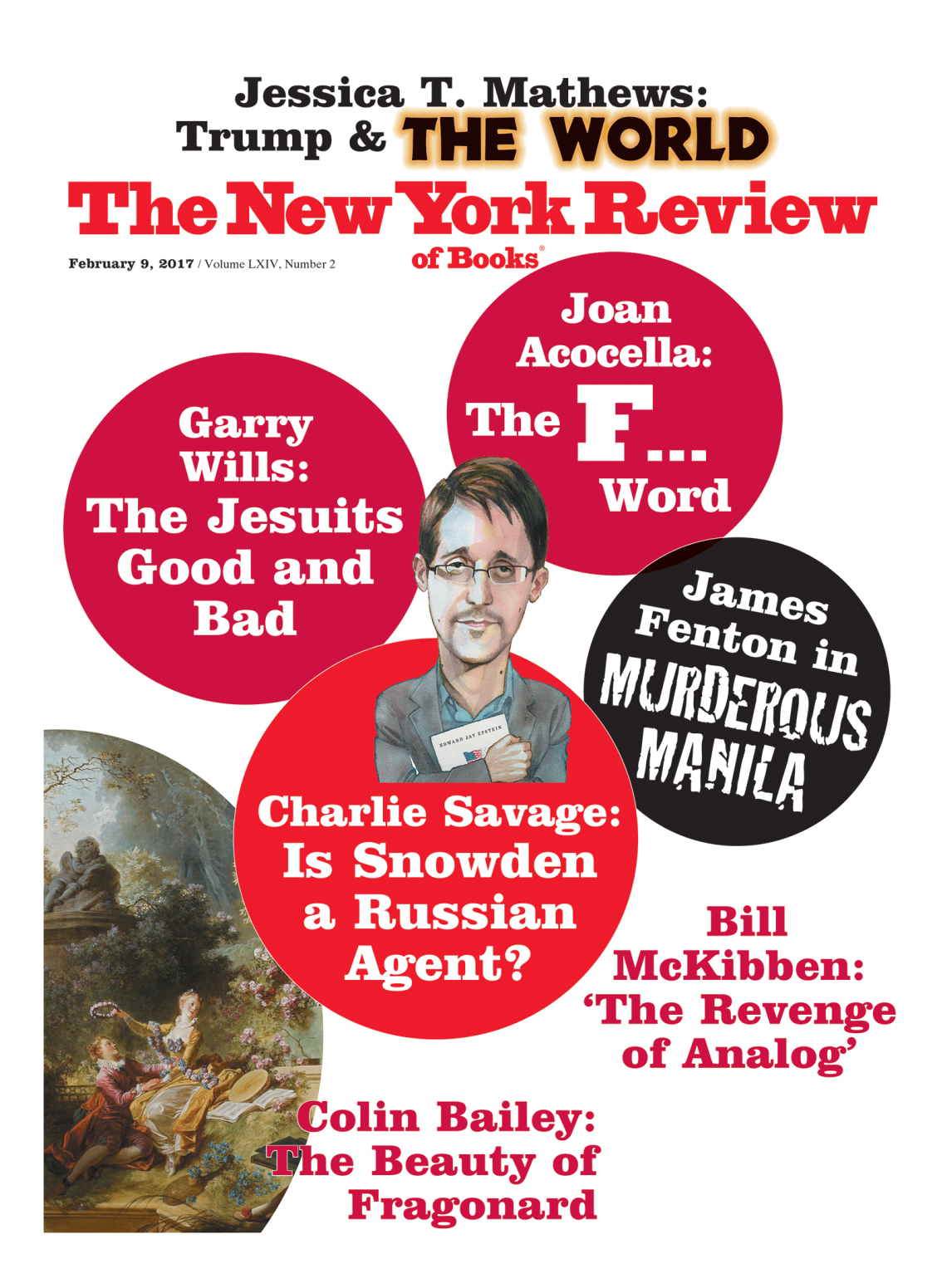

This Issue

February 9, 2017

Was Snowden a Russian Agent?

The F Word

Trump & the World

-

1

Counting from his first bureaucratic appointment as a county deputy Party secretary in 1982. ↩

- 2

-

3

See Andrew J. Nathan and Bruce Gilley, China’s New Rulers: The Secret Files (New York Review Books, 2002). ↩

-

4

Jérôme Doyon, “Rejuvenating Communism: The Communist Youth League as a Political Promotion Channel in Post-Mao China,” Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University and École Doctorale de Sciences Po, Institut d’études politiques de Paris, 2016. ↩

-

5

David Shambaugh, China’s Future (Polity, 2016). ↩

-

6

See my “Who Is Xi?,” The New York Review, May 12, 2016. ↩

-

7

Minxin Pei, China’s Trapped Transition: The Limits of Developmental Autocracy (Harvard University Press, 2006). ↩

-

8

“Ex-Army Leader Xu Caihou Had ‘a Tonne of Cash’ in Basement,” South China Morning Post, November 21, 2014. ↩

-

9

www.epochtimes.com/gb/14/12/25/n4326739.htm, news.ltn.com.tw/news/world/breakingnews/1278670, house.ifeng.com/pic/2014_12/21/38862063_0.shtml. I can’t confirm that these stories are true, however. ↩

-

10

David Barboza, “Billions in Hidden Riches for Family of Chinese Leader,” The New York Times, October 25, 2012.

Michael Forsythe, “Wang Jianlin, a Billionaire at the Intersection of Business and Power in China,” The New York Times, April 28, 2015.

“Xi Jinping Millionaire Relations Revealed Fortunes of Elite,” Bloomberg News, June 29, 2012.

Michael Forsythe and Jonathan Ansfield, “A Chinese Mystery: Who Owns a Firm on a Global Shopping Spree,” The New York Times, September 1, 2016. ↩ -

11

“Time Runs Out for ‘Brother Watch’ Yang Dacai,” South China Morning Post, August 31, 2013. ↩

-

12

A point suggested years ago by James C. Scott, Comparative Political Corruption (Prentice-Hall, 1972), pp. 88–91. ↩

-

13

Martin Wolf, “Too Big, Too Leninist—A China Crisis Is a Matter of Time,” Financial Times, December 13, 2016. ↩

-

14

James Leung, “Xi’s Corruption Crackdown: How Bribery and Graft Threaten the Chinese Dream,” Foreign Affairs, May/June 2015. ↩

-

15

A recent business biography of Jack Ma of Alibaba says little about his dealings with the government; Duncan Clark, Alibaba: The House That Jack Ma Built (Ecco, 2016). ↩

-

16

“Decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Some Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening the Reform,” China.org.cn, January 16, 2014; see also Arthur Kroeber, “Xi Jinping’s Ambitious Agenda for Economic Reform in China,” Brookings, November 17, 2013. ↩

-

17

University of California Press, 1966, Ch. 1, p. 58 (page number from second edition, 1968). ↩

-

18

See Ann M. Florini, Hairong Lai, and Yeling Tan, China Experiments: From Local Innovations to National Reform (Brookings, 2012); Joseph Fewsmith, The Logic and Limits of Political Reform in China (Cambridge University Press, 2013). ↩

-

19

Chris Buckley, “China’s Antigraft Enforcers Take on a New Role: Enforcing Loyalty,” The New York Times, October 22, 2016. ↩

-

20

Chen Qiufa, transferred from the chairmanship of Hunan Political Consultative Conference to the governorship of Liaoning. ↩

-

21

Lin Duo, promoted from secretary of the Liaoning discipline inspection commission to governor of Gansu. ↩

-

22

Francis Fukuyama, The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011); Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014). ↩

-

23

Francis Fukuyama, “Reflections on Chinese Governance,” Journal of Chinese Governance, Vol. 1, No. 3 (September 2016). ↩