When the surviving directorate of Freudian psychoanalysis reassembled after the disruption and dispersal of World War II, its members faced a situation of combined opportunity and risk. Their movement’s center of gravity had long been shifting westward from Vienna and Berlin toward London and New York, reaching more potential clients and supporters but also fostering schisms that threatened to discredit the whole institution. What was needed, it was agreed, was a means of generating solidarity behind the figure of Freud, the departed leader whose discovery of the unconscious, with the Oedipus complex at its core, could be celebrated by all parties.1

The urgency of that task of establishing solidarity was brought home to Anna Freud by the publication, in 1947, of Helen Walker Puner’s astute independent biography, Freud: His Life and His Mind, which dared to ascribe the founder’s precepts to his idiosyncrasies rather than to the objective nature of the psyche. Anna’s response was to commission a biography of her own, Ernest Jones’s three-volume opus of 1953–1957, that would profit both from Jones’s long intimacy with Freud and from documents that Anna would share with him but largely withhold from the public. Jones was chosen over a better-informed candidate, Siegfried Bernfeld, because he could be trusted to do Anna’s bidding—specifically, to establish a narrative of discovery that would make her father’s great breakthrough vividly persuasive, whether or not it happened to be true.

The trouble was, however, that by 1953 there were two competing creation myths. According to the one that Freud himself had propagated, all of his female patients had told him that they had been molested in childhood by their fathers; but Freud had stumbled across the Oedipus complex when he realized that those “memories” were only fantasies serving to disguise the girls’ own incest wishes. Freud’s published papers from 1896, however, along with his recently recovered letters to his best friend of the 1890s, Wilhelm Fliess, exploded that tale; it was Freud himself who had tried, unsuccessfully, to convince his patients that they had been abused. Moreover, the Fliess letters showed that Freud had initially thought of the Oedipus theme in connection with his own “hysteria”; and he had abandoned his “seduction theory” emphasizing childhood abuse many years before deciding that every psychoneurosis is rooted in repression of the Oedipus complex.

Which of the two imperfect stories was Jones going to tell, the one about Freud’s ceasing to believe his female patients or the one about his flash of introspection, assimilating all humankind to his own nervous case? If Jones had been writing for the sake of historical truth alone, he would have had to choose—or better yet, to expose the dubious features of both hypotheses. The point, however, was to encourage faith in psychoanalysis; and so, as in the gospels, Jones put forward both of the clashing versions, keeping silent about their incompatibility and allowing believers to embrace whichever tale they preferred. Thus Jones’s Freud was a paradox: at once a plodding inductivist, sifting clinical evidence and gradually awakening to its significance, and a transcendent genius who had seen the truth by looking inward.

Thanks in large measure to Jones’s florid biography, to the closely coordinated Standard Edition of Freud’s works edited by James Strachey, and to a tendentious, bowdlerized selection of the Fliess letters edited by Marie Bonaparte, Anna Freud, and Ernst Kris, the 1950s proved to be the heyday of Freudianism in the Anglophone world. In the 1970s, though, things fell apart in a hurry. The story of Freud’s solitary breakthrough was exposed as a legend by Henri F. Ellenberger, Paul Roazen, Frank Cioffi, and Frank J. Sulloway among others. Since then, psychoanalytically inclined authors have had to cope with, or carefully tiptoe around, the mounting evidence that Freud owed far more to his contemporary rivals than he had wanted us to know and that the original parts of his theory were also the most arbitrary.

In 1988, for example, in a hagiography-with-warts that was subtitled A Life for Our Time, Peter Gay acknowledged the threats to Freud’s grandeur posed both by recently released documents—most notably the full, and very disillusioning, Fliess letters published in 1985—and by skeptical studies, whose importance Gay nevertheless strove to minimize. Largely reproducing Jones’s self-canceling portrait of Freud, Gay employed his concluding “Bibliographic Essay” to belittle the growing cadre of scholars who had dared to question the master’s independence, his veracity, and even his competence. Now Freud biography by Freudians was getting to be more a matter of plugging leaks than of celebrating world-historical achievements.

The latest entry in this genre is Élisabeth Roudinesco’s Freud: In His Time and Ours, which won two prestigious awards when it was first published in France in 2014. Roudinesco’s title echoes Gay’s. She, too, feels that “our time,” a generation later, calls for a warier approach to the founder of psychoanalysis. And as we will see, she finds it necessary to concede a good deal more than Gay did to the now widely shared opinion that Freud’s discoveries had never occurred at all. Yet given Roudinesco’s background and history, it is hard to think of another author who would have been less likely to relinquish any portion of her faith in Freud.

Advertisement

For some forty years now, Roudinesco has been an eminence in the intellectual culture of France. Prolific historian, academic, psychoanalyst, and controversialist, she is best known as a staunch champion and the definitive biographer of Jacques Lacan, whose idiosyncratic “return to Freud” initiated a national love affair with psychoanalysis in the 1960s. Whether one regards Lacan, who died in 1981, as “a thinker of genius” and as “the greatest theorist of Freudianism of the second half of the twentieth century” (Roudinesco’s judgment) or rather as the most pompous of obscurantists, his impact was enormous; and Roudinesco chronicled it in abundant detail.2

Roudinesco’s 1993 biography of Lacan tested the limits of her loyalty to psychoanalysis. The book was unsparingly frank about its subject’s personal failings: greed, authoritarianism, a posturing vanity, sexual predation, and capricious cruelty. Nevertheless, Roudinesco insisted on his greatness, which was treated as an unexaminable fact. Lacan had endeared himself to Roudinesco by “decentering the Freudian subject” and recasting the biologically reductive Oedipus complex as a linguistic phenomenon. Although he had also represented the erect phallus as the square root of minus one, that was unobjectionable, too.

Lacan’s ideas lacked even a pretense of basis in research, but Roudinesco never thought to question them. As she has written elsewhere, she is a “daughter of psychoanalysis.”3 Her mother, Jenny Aubry, had been a close friend of Lacan’s and a founding member of his schismatic École Freudienne de Paris. “I had been immersed in the culture of this movement since my childhood,” Roudinesco disclosed. And she has continued to believe that psychoanalysis, both Freudian and Lacanian, is indispensable because, in a dehumanizing age, it posits a psychical self-division that mirrors the tragic complexity of existence.4

The most memorable display of Roudinesco’s Freudian affinity per se occurred in 1995, after the US Library of Congress announced a forthcoming exhibition, “Sigmund Freud: Conflict and Culture,” based on the holdings of its Freud collection. The show and its ancillary events and publications were to expound Freud’s achievements while also reflecting the recent “close critical reexamination” of his theory.5 As it turned out, however, only old-line Freudian loyalists were selected as advisers and catalog contributors. Troubled by such provincialism, several dozen scholars and others, including some psychoanalysts, courteously petitioned the library to add one independent member to the steering committee. Instead, to general amazement, the library announced that, owing to a shortfall of funds, the exhibition would be indefinitely postponed. That was all the impetus Roudinesco needed to take decisive action.

With the aid of a colleague, and garnering 180 signatures in all, Roudinesco addressed a petition of her own to the library’s director. Books committing “unheard-of violence” against Freud, she asserted, had been written by the organizers of the first petition, who had charged him with having sexually abused children, his sister-in-law, and other women. Now “the inquisitors” had been caught plotting to keep the exhibition from ever opening. Roudinesco’s document urged the library’s director not to yield to the “extortion of fear” and the “witch hunt” of such “politically correct” zealots. Yet it was clear to anyone who saw the first plea that its signers had meant only to improve the exhibition, not to torpedo it. (The show did take place, with the cooperation of the dissenting scholars, in 1998.)

The language of Roudinesco’s coauthored petition, though vitriolic, was mild in comparison with what she wrote on her own for French publications. The enemies of the Freud exhibition, she observed, reminded her of “ayatollahs” and Nazis hunting down “Jewish Freudians.”6 Meanwhile, she lobbied tirelessly with influential academics, urging them to denounce those she saw as the McCarthyist enemies of free speech. Patently, however, the Joe McCarthy of the Library of Congress episode was Roudinesco herself.

Now, with Freud: In His Time and Ours, Roudinesco takes her turn at characterizing the whole career of the first psychoanalyst. She does so at length and in broad historical scope. And it would appear at first glance that her mood has considerably mellowed. Reviewers, certainly, have taken her at her word: she is simply offering an unprejudiced account of Freud’s life, hiding nothing.

Advertisement

Roudinesco begins with Freud’s ethnic, class, and religious background and moves through his childhood in Moravia and Vienna, his schooling and university education, his reluctant choice of a medical career, his visit, on a fellowship, to Jean-Martin Charcot in Paris, his courtship, marriage, and family life, his livelihood as a private practitioner, his invention of psychoanalysis, and, most extensively, his role as the leader of a movement whose centrifugal development frustratingly eluded his control. At no point does the author pause to indulge in special pleading for Freudian concepts and tenets.

On the contrary, at the outset of her study Roudinesco ventures a boldly negative observation. “What Freud thought he was discovering,” she declares,

was at bottom nothing but the product of a society, a familial environment, and a political situation whose signification he interpreted masterfully so as to ascribe it to the work of the unconscious.

Although she never actually makes a case for that proposition, it liberates her at one stroke from having to defend ideas that appear to have fallen permanently out of favor.

Freud’s theory, Roudinesco now holds, is best understood not as an accurate picture of the mind but as a serving of warmed-over Romanticism, spiced with a misleading dash of materialist determinism. Having thus given up on Freudian science, she can serenely acknowledge Freud’s habit of forever “contradicting and combating himself.” She sees no reason, furthermore, to emulate Jones and Gay in quarantining his occultist inclination from the rest of his thought. For Freud, Roudinesco asserts, “it was a matter of proclaiming, against the overly rational primacy of science, a magical knowledge that escaped the constraints of the established order.” Thus, when Freud commends his clinical regimen as a form of telepathy and when he jumbles the distinction between psychological and organic domains, asserting that germ cells are “narcissistic” and carry a “death drive,” Roudinesco is unfazed. She expected just such mysticism from an intellectual heir of Franz Anton Mesmer.

Unlike Jones and Gay, Roudinesco acknowledges that the Oedipus template was imposed on Freud’s patients rather than deduced from their cases; and, further, that its adoption caused him to become more glib, “tossing about willy-nilly the sacrosanct Oedipus complex” and applying it “to the most banal conflictual situations.” She grants, moreover, that when he ventured into anthropology (Totem and Taboo), religion (The Future of an Illusion), sociology (Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego), biography (Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood), and history (Civilization and Its Discontents), he brushed aside inconvenient facts while appropriating each discipline to his overriding theme.

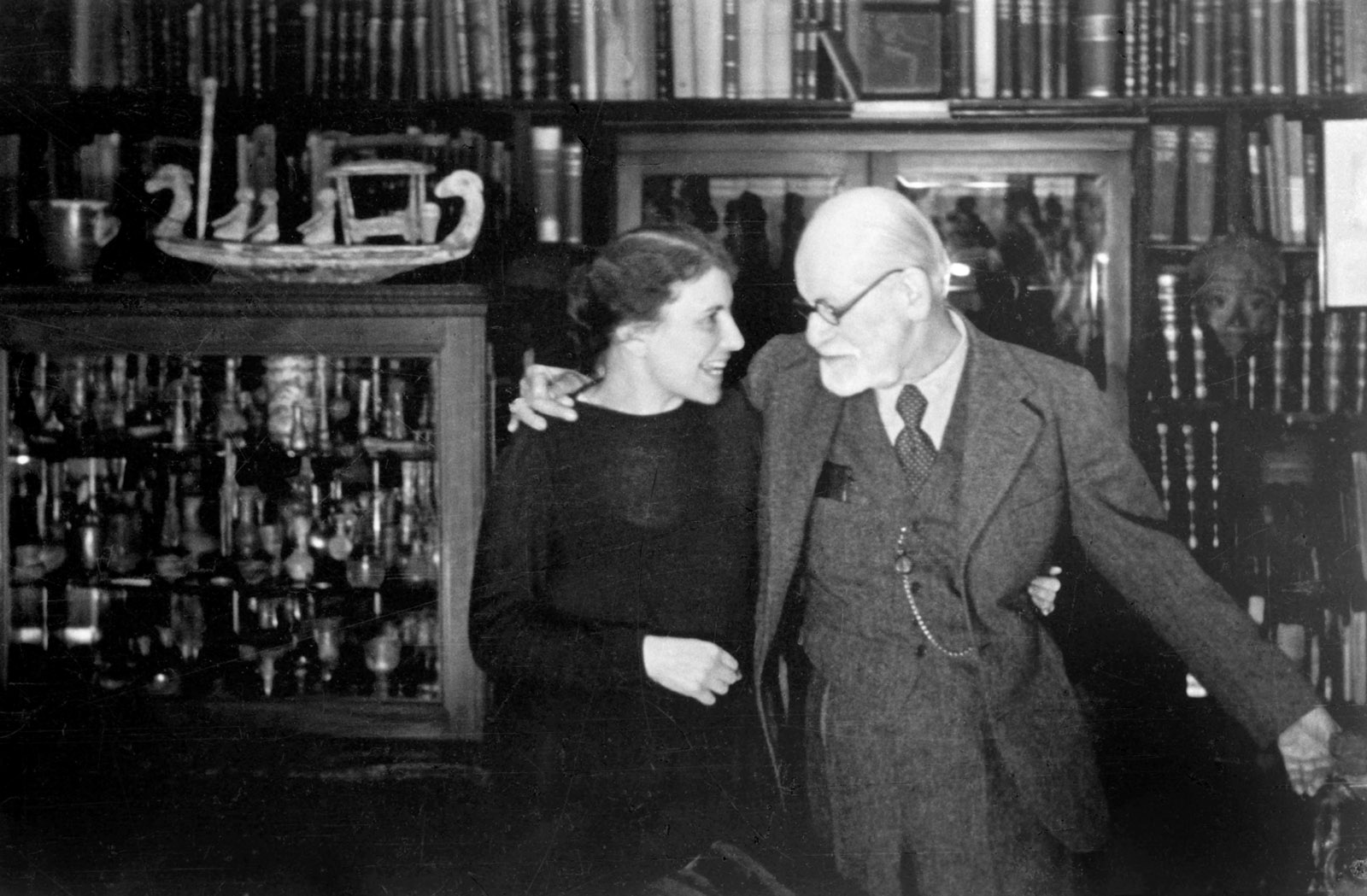

In Roudinesco’s narrative, Freud comes off looking unobservant and self-absorbed rather than psychologically keen. She reminds us, for instance, that he discounted the many signs that C.G. Jung was never going to be his compliant heir. Again, in 1919 he was easily deceived by a fellow psychoanalyst’s forgery of a girl’s diary, allowing himself to be “hoodwinked by a fraud that sprang directly from his doctrine.” Most remarkably, having taken his own daughter Anna into analysis with the reckless goal of “awakening her libido,” he still failed to grasp that her sexual preference was for women.

Likewise, Roudinesco indicates that Freud was slow to recognize the Nazi menace to Jews in general and psychoanalysis in particular. She tells how the ailing patriarch, obsessed with his privately chosen enemy, the Roman Catholic Church, blinded himself to the greater threat and then, when it materialized, failed to take a principled stand against it—even acquiescing in the purging of Jews from the German branch of his movement, which was surviving in name only. Although Roudinesco doesn’t say so, that episode chillingly dramatizes the extent to which Freud subordinated all values to the cause of forwarding his brainchild without regard to its social or medical utility.

No less surprising than Roudinesco’s deflationary account of Freud’s doings, however, is her continuing reverence for him. Freud, she announces, “imposed on modern subjectivity a staggering mythology of origins whose power seems more alive than ever….” And at the end of her book she voices a hope that “for a long time yet, [Freud] will remain the great thinker of his time and ours.” This is very strange. A great thinker is surely one whose insights are far more cogent than those of his strongest competitors; but Freud as Roudinesco presents him was merely a man with an obsession. True, he lent that obsession literary resonance and convinced millions that he belonged in the company of Copernicus and Darwin. But the achievement was won—as Roudinesco will not admit—by boasting, cajoling, question begging, denigrating rivals, and misrepresenting therapeutic results.

Unable to argue that Freud’s theory was correct but feeling as bonded to him as ever, Roudinesco finds herself in a dicier predicament than with Lacan in 1993. Back then, she hoped that the French intellectual elite’s faith in the Lacanian system would be strong enough to survive her revelations about his deplorable character. Now, however, she appears to have calculated that the only way to appease the critics of psychoanalytic theory is to agree with them. She does so, nominally, but without conviction, for at numerous junctures she draws on Freud’s assumptions as if they hadn’t been disallowed at all.

It is not in Roudinesco’s nature to admit that she has been obliged to change her mind about anything. She favors the attack mode; and as we saw in the Library of Congress dispute, she prefers to denounce adversaries for outrageous claims that they didn’t make. Now, in Freud: In His Time and Ours, she covers her confusion by reverting to that same practice.

From various comments, some of them tucked away in notes, we gather that Roudinesco is on a mission to protect her idol from vicious “Freud bashers” and practitioners of “revisionist madness” who have “made Freud out to be a swindler, a rapist, and incestuous.” Some of them, she declares, even charge him with having “assassinated” a dear friend so as to eliminate him as a rival. Roudinesco holds that such crazies, rather than Freud’s own deeds and limitations, have subjected him to public disdain.

We never learn, either from this book or from any of Roudinesco’s others, which villains have spread the lie that Freud was an incestuous rapist and murderer. She does, however, single out the philosopher of science Adolf Grünbaum and the independent historian Peter J. Swales as having busied themselves “tearing apart Freud’s doctrine and Freud himself, the master having become once again a diabolical scientist guilty of engaging in sexual relations within his own family.” But Grünbaum has never concerned himself with Freud biography, and his objections to Freud’s claims are drily technical. As for the maverick Swales, knowledgeable scholars on both sides of the Freud quarrel respect his meticulously researched investigations, which are too seldom read to have affected Freud’s image with the broad public.7

To say that Grünbaum and Swales have read Freud with more care than Roudinesco would be an understatement. Consider, for example, her treatment of Freud’s first book, Studies on Hysteria, cowritten with Josef Breuer. Roudinesco mixes up Freud’s patients, mistaking the English governess “Miss Lucy R.” for the Hungarian heiress “Elisabeth von R.” She contrasts Freud and Breuer’s “cathartic method” with hypnotism, evidently unaware that hypnotism was the engine of that method. And she confounds “hysteria” with “neurosis” and then bizarrely equates it with “insanity.” Such slippage forecloses any possibility of establishing what Breuer and Freud thought they were accomplishing and why they soon became antagonists.

There is, finally, the question of whether Roudinesco’s Freud, although much reduced from the godlike personage touted by her predecessors, is the man himself or a version she has constructed with ongoing protective intent. The ultimate goal of Freud: In His Time and Ours, I would say, is to spare its protagonist from dismissal as a man who, in his ex-friend Fliess’s annihilating words, “merely reads his own thoughts into other people.”8 Those thoughts were overwhelmingly sexual, and they were inflamed by a drug, cocaine, that Freud had begun ingesting in 1884 and was once again using in his years of psychoanalytic “discovery.” In order to forestall this unwelcome line of inquiry, both Jones and Gay, following Freud’s own lead in his canny reminiscences, strained to depict him as a neutral investigator who, living a life of impeccable bourgeois virtue, had been ambushed by his patients’ emphasis on the repulsive topic of sex. And now Roudinesco follows suit.

Ignoring clear evidence that Freud’s early patients rejected and even mocked his sexual explanations of their troubles, Roudinesco maintains that they “asserted” and “often recounted” erotic revelations to an abashed, “puritanical” Freud—one who was so high-minded that he decided to abstain from sexual intercourse just on principle. Overlooking his prescription of 1908—“the cure for nervous illness arising from marriage would be marital unfaithfulness”9—Roudinesco endows him with a lifelong “horror of adultery.” According to her, moreover, he always regarded his wife Martha with “a sort of adoration.” Thus it is unthinkable that he could ever have lusted after her sister Minna, much less have seduced her (as his close associates believed, and as Minna herself evidently confessed to Jung). As for cocaine, Roudinesco assures us that Freud “definitively” forswore it in 1892—a contention that is amply belied by his surviving letters to Fliess and even by The Interpretation of Dreams.

There is room for debate about the nature of Freud’s private life, which, as even Jones admitted, was assiduously hidden from view.10 Roudinesco’s straw-man polemics, however, admonish us not to go there, for Freud’s respectability must be preserved at all cost. Yet if this man really discovered nothing and nevertheless persuaded the world to regard him as a titan of science, he was one of the most audacious figures in the history of thought. That is profoundly interesting; Roudinesco’s bourgeois gentleman is not.

-

1

In Freud’s construal, every child, on pain of incurring a later psychoneurosis, must manage to overcome an “oedipal” desire to murder its same-sex parent in order to clear the way for copulation with the other one. Fear of horrible retribution presumably relegates the Oedipus complex to the unconscious, where Freud allegedly found it lurking. ↩

-

2

Élisabeth Roudinesco, Jacques Lacan, translated by Barbara Bray (Columbia University Press, 1997), p. 397; Why Psychoanalysis?, translated by Rachel Bowlby (Columbia University Press, 2001), p. 118. ↩

-

3

Jacques Derrida and Élisabeth Roudinesco, For What Tomorrow…, translated by Jeff Fort (Stanford University Press, 2004), p. 175. ↩

-

4

See Chapter 3, “The Soul Is Not a Thing,” of Roudinesco’s Why Psychoanalysis? ↩

-

5

“Freud Exhibition to Open at LC,” Library of Congress Information Bulletin, June 13, 1994. ↩

-

6

Roudinesco, “Le revisionisme antifreudien gagne les États-Unis,” Libération, January 26, 1996. ↩

-

7

Roudinesco herself has learned from Swales. Although he has vanished from the index of her English-language text (he was there in the French), she adopts insights from several of his articles, acknowledging some borrowings but not others. ↩

-

8

The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess, 1887–1904, translated and edited by Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson (Belknap Press/Harvard University Press, 1985), p. 447. ↩

-

9

Freud, Standard Edition, Vol. 9, p. 195. ↩

-

10

“Everything points to a remarkable concealment in Freud’s love life,” Jones nudged. And elsewhere: “One sensed an invisible reserve behind which it would be impertinent to intrude, and no one ever did”; and “there were features about his attitude that would seem…to justify the word privacy being replaced by secrecy.” See The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud, three volumes (Basic Books, 1953–57), Vol. 1, p. 124; Vol. 2, p. 408. ↩