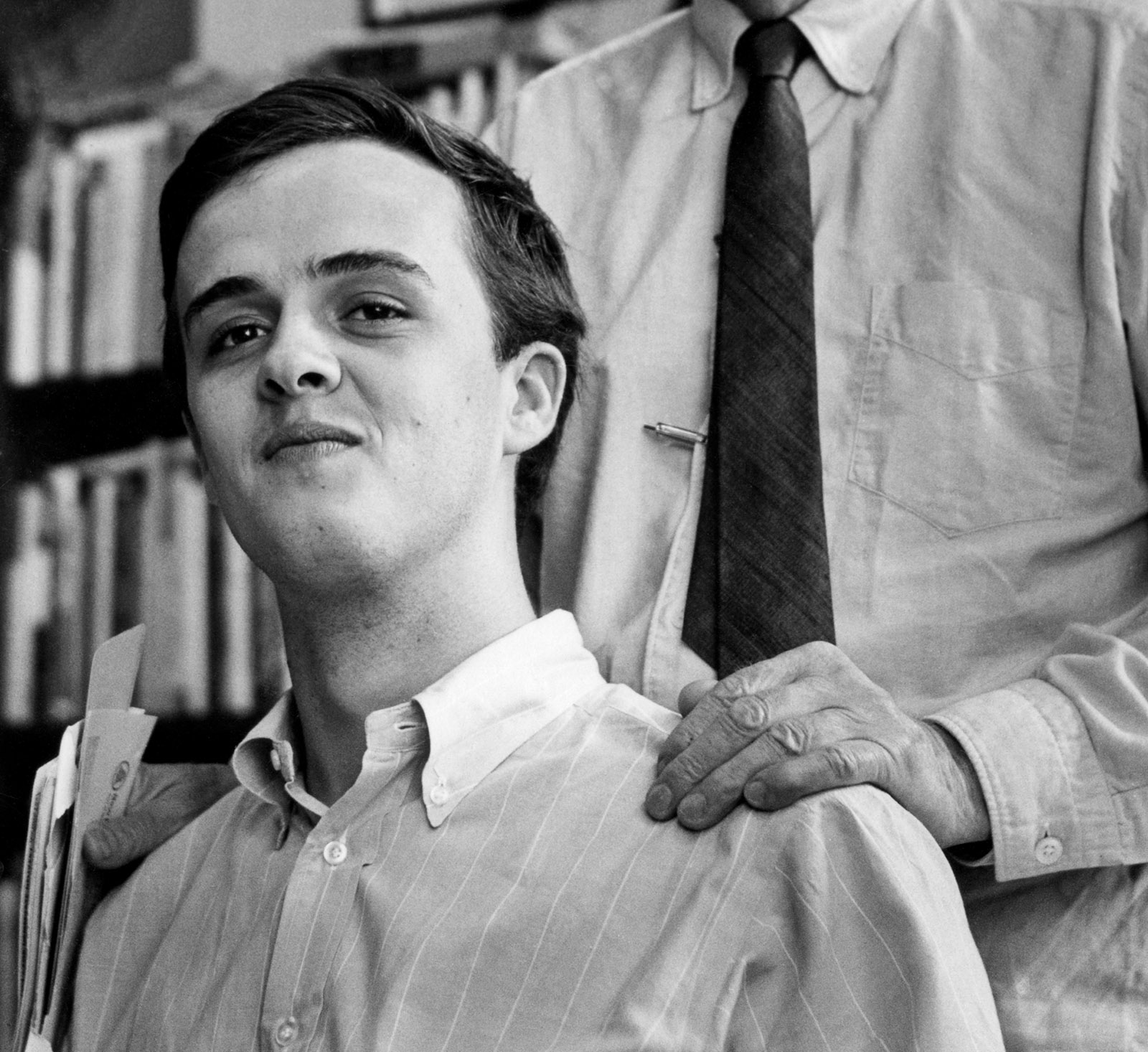

James Tate, who died the summer before last at the age of seventy-one, after being in poor health for many years, was one of the most prolific and admired American poets from the time his first book of poems, The Lost Pilot (1967), was selected for the Yale Series of Younger Poets while he was still a student at the University of Iowa, making him one of the youngest poets ever to receive that honor. The title poem is dedicated to his father (1922–1944), a B-17 pilot who was killed on a bombing raid over Stuttgart during World War II when his son was four months old. The plane crashed, but his remains were not found, though the rest of the crew survived. In the poem, his son imagines him still orbiting the earth and hopes to cajole him to land for an evening, so that he could touch and read his face the way a blind man touches a page in braille, promising that he would not turn him in, nor force him to face his wife, so he could go back to his crazy orbiting without his son asking and trying to understand what it means to him.

Tate was born in Kansas City in 1943, in a family that had no memory of ever living in any other state except Missouri. Both of his maternal grandparents worked in a bank. The others in the family were shopkeepers, clerks, plumbers, and handymen, and the women they married were deeply religious, spoke in tongues, attended churches with names like Full Grace Tabernacle of the Holy Spirit, and believed in faith healing.

Tate’s father’s father was a one-legged caretaker at the Kansas City Zoo and lived in a shack on the premises, where Tate and his mother went to stay after her husband was inducted into the air force, but the old man and his wife both died of grief a few months after they learned of their son’s death, so Tate and his mother moved in with her parents. The seven years that they lived with them and three aunts and an uncle he recalled as an idyllic time in his life. There were several kids around his age on the same block to play with and roam the streets with. All that ended when his mother married a handsome man who looked like his father, but who turned out to be a dangerous lunatic who shot holes in their house with a .45 automatic.

Her next marriage was even worse. The new husband was a traveling salesman who sold shock absorbers. He was gone all week and on weekends he used to beat his wife black and blue with her son watching. Eventually Tate, who was sixteen by then, stuck a gun to the man’s head and that ended that marriage. He did poorly in school—his fourth-grade teacher even suggested that he might be mentally deficient and ought to be taken out of school and placed in a home for children like him—and graduated high school 478th out of a class of 525; finding himself friendless since all his buddies were heading for college, he sat around the house depressed.

Listening to the radio one day, he heard a disc jockey read an ad for recruits to the Foreign Legion: it was the station’s idea of a joke, but to the surprise of the people there, one scrawny youth showed up the next day prepared to enlist. In a panic now, Tate got in touch with a school he knew had to accept him because he was a state resident, Kansas State College in Pittsburg, where to his surprise he started enjoying his classes and taking his studies seriously. He wrote his first poems there while ransacking the library and reading Hart Crane, William Carlos Williams, Rimbaud, Baudelaire, García Lorca, Rilke, Apollinaire, and other poets. What helped, too, was meeting a few bohemian types in town: an artist, a jazz musician, a theater director, and a teacher at the college, all of whom took an interest in him and encouraged him to write.

With the sole exception of a handful of early poems, what makes Tate’s poetry unlike that of most American poets is that it is not centered on his life. The speaker in poems, he said, was a Beckett type, some nameless representative of humanity. Asked about a straightforward prose account he once wrote about his Kansas City childhood, he explained that he wanted to clear it out of his system so that that kind of material wouldn’t get into his poetry.

This, of course, is not what one would expect from a poet with an unusually interesting past; nevertheless, this is the kind of poet Tate was. He didn’t care for confessional poetry and hated narcissists, saying that he had no wish to make love to himself in a mirror. “I like to start out of the air and then find a subject later, if at all,” he said. Even when he had a subject in mind, he’d rush to derail it, and as soon as it got going in another direction, he’d derail it again. Unlike poets eager to buttonhole the reader and unburden themselves, Tate saw the world the way a short-story writer or a novelist would, more fascinated with the lives of other human beings than with his own. He wrote stories alongside writing poetry, and even planned a novel at one time that he hoped would convey a complex vision, both dreamlike and real, banal, cruel, and with a sumptuous sense of our lives.

Advertisement

The Lost Pilot is still a very good book. Beyond its much-admired title poem, there are a number of others in which Tate’s astonishing gift for images and his ear for colloquial language are already present. The ten books he published over the next thirteen years—The Oblivion Ha-Ha (1970), Hints to Pilgrims (1971), Absences (1972), Viper Jazz (1976), Riven Doggeries (1979), Constant Defender (1983), Reckoner (1986), and Distance from Loved Ones (1990)—are full of poems so different in style and temperament that they could be the work of more than one poet. There are short lyrics, longer poetic sequences, and prose poems, many of them as original as any ever written in American poetry.

Surrealism was a big influence. Tate was not the only poet in those years to fall under its spell, but he grew irritated when called a Surrealist later on, explaining that though he loved the poetry of Benjamin Péret and Robert Desnos and thought André Breton had some wonderful poems, he had no interest in Breton’s theories. Writing just one kind of poem over and over did not appeal to him. Besides, Wallace Stevens, William Carlos Williams, and Hart Crane meant more to him than any European or South American he read and admired. “A serious poet should try everything,” he said in a Paris Review interview, and he did just that.

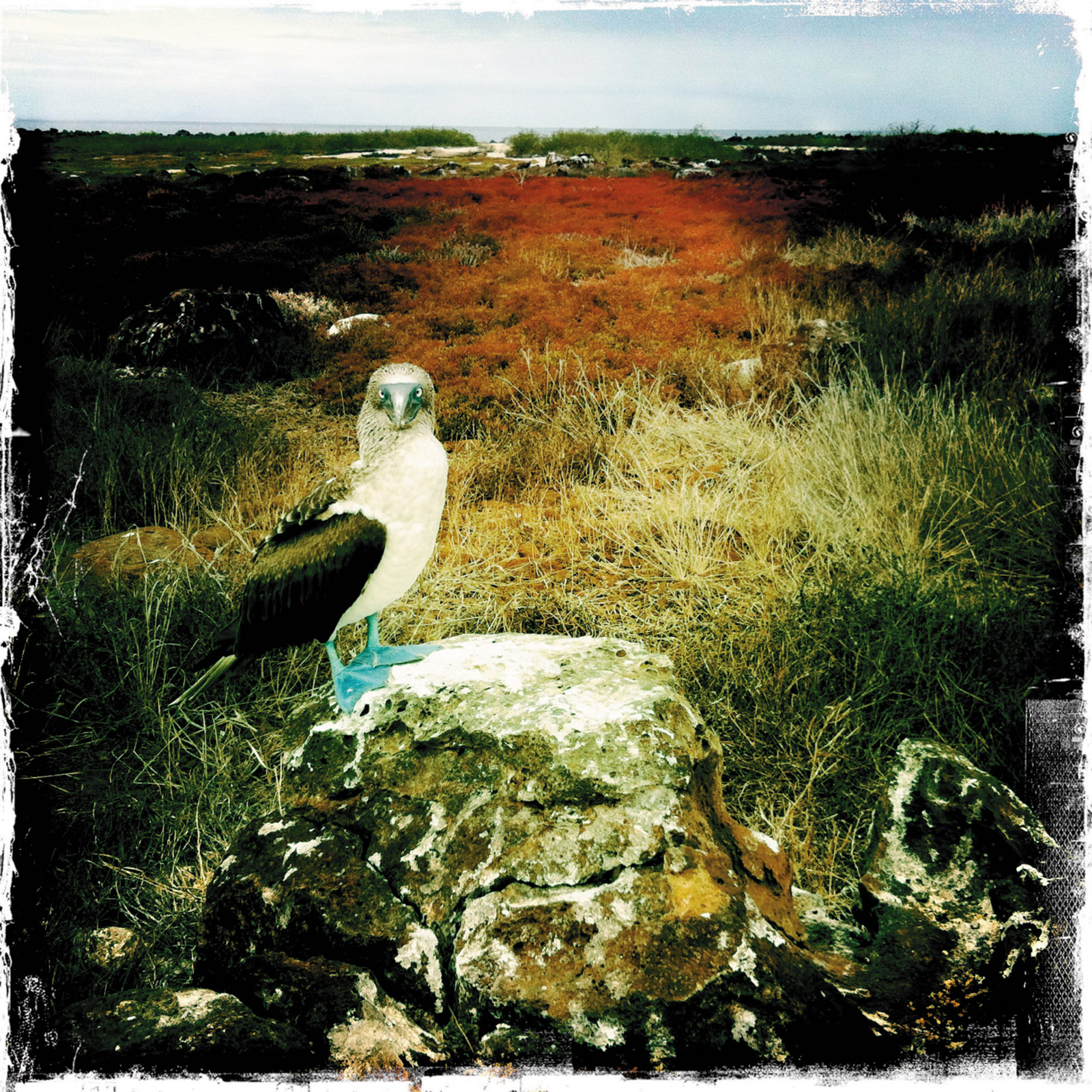

THE BLUE BOOBY

The blue booby lives

on the bare rocks

of Galápagos

and fears nothing.

It is a simple life:

they live on fish,

and there are few predators.

Also, the males do not

make fools of themselves

chasing after the young

ladies. Rather,

they gather the blue

objects of the world

and construct from thema nest…

MYSTIC MOMENT

I faced the Star Maker, the candy butcher

from the window of a Pullman car

just outside Pueblo, Colorado,

from a plush and velvet world

with plugs of tobacco

outside a jelly factory.

The vibration of names, a cardinal—

Behind me, Gabriel.

Rounded up like rats

on Metacombie Kay…

LEAPING WOMAN

The leaping woman arrives in an ambulance of starlight. A harness of wet pins shoots through the pure whiteness of her foaming team of white Cadillacs, white hounds in a lost pool of whiteness. An arm from a window touches half-a-moon; silhouetted aerials switching the night into miracles, miracles of green fiery air, of locomotion and lullaby. Hammer of gigantic thrills. O spew, circle her brilliant black curls! Ash, marble flame, O detective hummingbird: She’s filled with the desire to stand absolutely still!…

GOODTIME JESUS

Jesus got up one day a little later than usual. He had been dreaming so deep there was nothing left in his head. What was it? A nightmare, dead bodies walking all around him, eyes rolled back, skin falling off. But he wasn’t afraid of that. It was a beautiful day. How ’bout some coffee? Don’t mind if I do. Take a little ride on my donkey, I love that donkey. Hell, I love everybody.

These four poems are as different as poems can be. “The Blue Booby” reads like the notes of an amateur ornithologist who’s been observing the mating ritual of these birds; “Mystic Moment” evokes the Romantic, visionary rhetoric of poets going back to Whitman; and “Leaping Woman” is pure Surrealism, a product of automatic writing, that state of abandon when our critical faculties hang an out-to-lunch sign on our doors and words pour out freely, which the poet writes down in a hurry, and later edits on the lookout for some outrageously pleasing combination of words amid pages of nonsense. “Goodtime Jesus” has no precedent in anybody’s poetry. It is a hilarious and touching poem, pairing mischief and piety as if they were meant to be the most natural of companions.

Mark Twain once described a coconut tree as being like a feather duster struck by lightning. He, like Tate, hailed from Missouri. The author of “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” and the poet from Kansas City shared a fondness for tall tales. They never passed up an opportunity to amuse their readers or pull their legs no matter what the subject was. “You go to your desk with the intention of writing a suicide note,” Tate said, “and end up writing the funniest piece you’ve ever written.”

Advertisement

Tate grew up in the 1950s watching comedy shows on TV, most of which employed old vaudevillians for whom clowning and slapstick were an integral part of their skits. I recall the two of us reminiscing about Jimmy Durante, Sid Caesar, Milton Berle, Red Skelton, Ernie Kovacs, and others from that era and still laughing about their gags. This was the kind of humor Tate kept sneaking into his poems for the rest of his life. “Homespun Surrealism,” John Ashbery calls it somewhere. Some readers, of course, don’t know what to make of it, dead sure that laughter is a sign that one doesn’t take one’s art and the world out there seriously. Solemnly funny is what Tate was as a poet, since his poems are often heartbreaking.

Worshipful Company of Fletchers (1994), Shroud of the Gnome (1997), and Memoir of the Hawk (2001) have 260 poems between them and include many of his finest works. The profusion of styles of the earlier books and even their prosody, with stanzas of the same length and carefully calculated line breaks, are gone and replaced by poems that are much more prosy and narrative, sounding often like fables and parables, but managing to be as tightly structured as the earlier ones. A poem of Tate’s has its own inner logic, a logic he discovers as his imagination takes him from whatever his starting point was to someplace he never expected to find himself. I know that’s how he wrote because we collaborated on a few poems in our youth. I remember sitting over a sheet of paper, holding a pen, and listening to him in awe. Lines of poetry would be popping out of his head like popcorn out of a frying pan until I told him to please slow down. His imagination was inexhaustible and free of inhibitions.

Opening lines have as much importance in his poems as they do in stand-up comedy. They set the scene, create expectations. We want to hear the rest, expecting there’ll be surprises along the way, with the biggest waiting at the end:

He was a bold little tyke even at the age

of three. He would have fought bulls if given

half a chance. He would have robbed trains.

He would have rescued women from waterfalls…

(“Burnt Green Earth”)

Speaking of sunsets,

last night’s was shocking.

I mean, sunsets aren’t supposed to frighten you, are they?

Well, this one was terrifying.

People were screaming in the streets.

Sure, it was beautiful, but far too beautiful…

(“Never Again the Same”)

Tate rarely disappoints. He knows that in writing a comic scene surprise and timing are all-important:

THE SPLENDID RAINBOW

The lightning woke us at about three A.M.

It sounded like a war was going on out there,

the drumrolls, the cannons exploding, the bomb

blasts, the blinding flashes. The electricity

was out. I found the flashlight and lit some

candles. The roof was leaking and the rain

was lashing the windows so savagely they rattled

in their casings. “What are our chances of

dying?” Denny asked. “Almost certain,” I

said. We sat on the edge of the bed and held

onto one another. The lightning bolts were striking

all around us. “Denny,” I said, “You are very,

very beautiful and I love you with all my

heart.” “I’ll take that to my watery grave,”

she said, “and smile through eternity.” Then

we kissed and the sun came up and the rain

stopped and the birds started to sing, a bit

too loudly. But, what the hell, they were in

love, too.

Couples and their squabbles fascinated him and he wrote about them often, but usually with tongue firmly in cheek, as in “The Splendid Rainbow.” He was a genial, good-natured commentator on people’s lives. It’s not just they who drew his attention, but also various innocent bystanders, such as cats, dogs, donkeys, goats, birds, bugs, and other creatures going about their business while we enact our dramas and our farces. In one poem, he describes a ladybug walking, thinking happy thoughts, proud of its five spots; in another, he admires ducks in a duck pond looking perfect in their duckiness. “When/they quacked,” the poem says, “it really meant quack.” Such idyllic scenes are frequent in his poetry, though he never forgot that we are a violent people too, “ready to shoot a fly for just being a fly,” as he wrote.

The poems in Return to the City of White Donkeys (2004), The Ghost Soldiers (2008), and Dome of the Hidden Pavilion (2015) read even more like stories. They are longer and have busier plots, less humor, and a darker view of this country. The setting, as in his previous books, continues to be a nameless town in New England with a small downtown, a couple of banks, a post office, a pharmacy, and a cast of characters one would call typical, except there’s something not quite right about them.

Put this way, that doesn’t sound like a subject that would inspire poetry, even though there is a long-forgotten precedent. Edgar Lee Masters’s Spoon River Anthology, published in 1915, is a collection of verse epitaphs that narrates the lives of 212 residents of a fictional small town in Illinois—in their own voices, from beyond the grave. I’m not suggesting that it was a model, but suspect that it comes from the same wish to leave a record, in Tate’s case of the death of the American Dream and the fear and trepidation left in its wake. “On the way to work this morning,” a poem begins, “the newsman on the radio said, ‘A big part of reality has been removed, it has been reported. Details are not available at this time. It’s just that, I am told, you will find things different on your drive to work this morning….’”

Some of the titles in these later books tell us what was on his mind: “The Government Man,” “The Secret War,” “The Enemy,” “The Investigation,” “After the War,” “The Soldiers’ Rebellion,” “The Wrong Man,” “The Lost Army,” “Possible Suspects”—subjects that by and large, judging by their poems, other Americans poets have somehow managed to ignore. Here’s a poem of Tate’s called “Bounden Duty”:

I got a call from the White House, from the

president himself, asking me if I’d do him a personal

favor. I like the president, so I said, “Sure, Mr.

President, anything you like.” He said, “Just act

like nothing’s going on. Act normal. That would

mean the world to me. Can you do that, Leon?” “Why

sure, Mr. President, you’ve got it. Normal, that’s

how I’m going to act. I won’t let on, even if I’m

tortured,” I said, immediately regretting that “tortured”

bit. He thanked me several times and hung up. I was

dying to tell someone that the president himself called

me, but I knew I couldn’t. The sudden pressure to

act normal was killing me…

What used to be regarded as one man or woman’s delusion has become an outbreak of collective paranoia. Wars without end, terrorism, gun violence, torture, surveillance, and fearmongering have taken their toll on this community. A bum holding a cheap pint of wine walks up to a man and tells him that it’s all rushing away. Can’t you feel it? What’s rushing away? The man asks. Time, it got uncorked, the bum replies. There’s no stopping it now. It’s like the wind in my hair. He’s one of the many characters whose dark premonitions about our future haunt these poems.

Reading his last book, Dome of the Hidden Pavilion, one comes to understand that Tate’s poetry is all of a piece. A poet who lost his father in one war and kept him alive for years imagining that he survived, lost his memory, and went on living somewhere ends where he started with a feeling of horror at these other wars, their ghost soldiers, and the unhappiness they brought. If he was inconsolable about his father, so were these countless other people whose grief he tried to imagine. He coped with his ghosts by making up stories that often turned out to be poems, and poems that turned out to be stories—it didn’t make any difference to him what one called them. “I had voices in my head and whole characters speaking to me,” he said. He wrote every day even when he was ill and in great pain.

The real mystery about Tate turned out to be his sense of humor, which he kept to the very end. As he said in an interview, “I do believe in some kind of humility, which I think keeps you from being morbidly serious about your own fate.” And he took that advice. After he died, his wife found this poem in his old typewriter. It appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of The Paris Review. It’s the last one he wrote and it was about him:

I sat at my desk and contemplated all that I had accomplished

this year. I had won the hot dog eating contest on Rhode Island.

No, I hadn’t. I was just kidding. I was the arm wrestling champion

in Portland, Maine. False. I caught the largest boa constrictor

in Southern Brazil. In my dreams. I built the largest house

out of matchsticks in all the United States. Wow! I caught

a wolf by its tail. Yumee. I married the Princess of Monaco.

Can you believe it? I fell off of Mount Everest. Ouch! I walked

back up again. It was tiring. Snore. I set a record for sitting

in my chair and snoring longer than anybody. Awake! I set a record

for swimming from one end of my bath to the other in No Count,

Nebraska. Blurb. I read a book written by a dove. Great! I slept

in my chair all day and all night for thirty days. Whew! I ate

a cheeseburger every day for a year. I never want to do that again.

A trout bit me when I was washing the dishes. But I couldn’t catch

him. I flew over my hometown and didn’t recognize anyone. That’s

how long it’s been. A policeman stopped me on the street and said

he was sorry. He was looking for someone who looked just like

me and had the same name. What are the chances?