A little more than halfway through Elias Khoury’s novel Broken Mirrors, the main character, Karim Shammas, meets an architect from Solidere, the real estate company that razed and rebuilt downtown Beirut after Lebanon’s ruinous civil war. The architect shows Shammas a computer program that works like the video game SimCity in reverse: instead of building cities, it flattens them. As Shammas inspects a virtual model of Beirut’s elegant city center, built under the French mandate, “suddenly the buildings began to fall, one after another, each disappearing behind a mass of dust before collapsing, broken up into a heap of stones and sand.” Shammas, who has a love–hate relation to his hometown, is nevertheless alarmed. “What kind of person demolishes his own memory?” he asks. But the architect only sneers. “Memories! This is a country without a memory. What use is memory? Memories of crap and shit, c’est fini.”

The demolition man has a point. Who wants to remember a civil war that nobody won? After local factions—Catholics, Muslims, and Druzes, among others—fought to a brutal stalemate, the Saudi-brokered Taif Agreement, signed in 1989, granted peacekeeping duties to Syria, which occupied Lebanon for the next sixteen years. None of the country’s sectarian and political groups was innocent, but all could equally claim to be victims. With no national consensus about what had happened or who was to blame, the premise of postwar reconciliation was a willingness to forget. The state gave warlords of all factions an official amnesty—many are now back in power—while refusing to investigate the cases of 17,000 Lebanese who disappeared during the conflict.

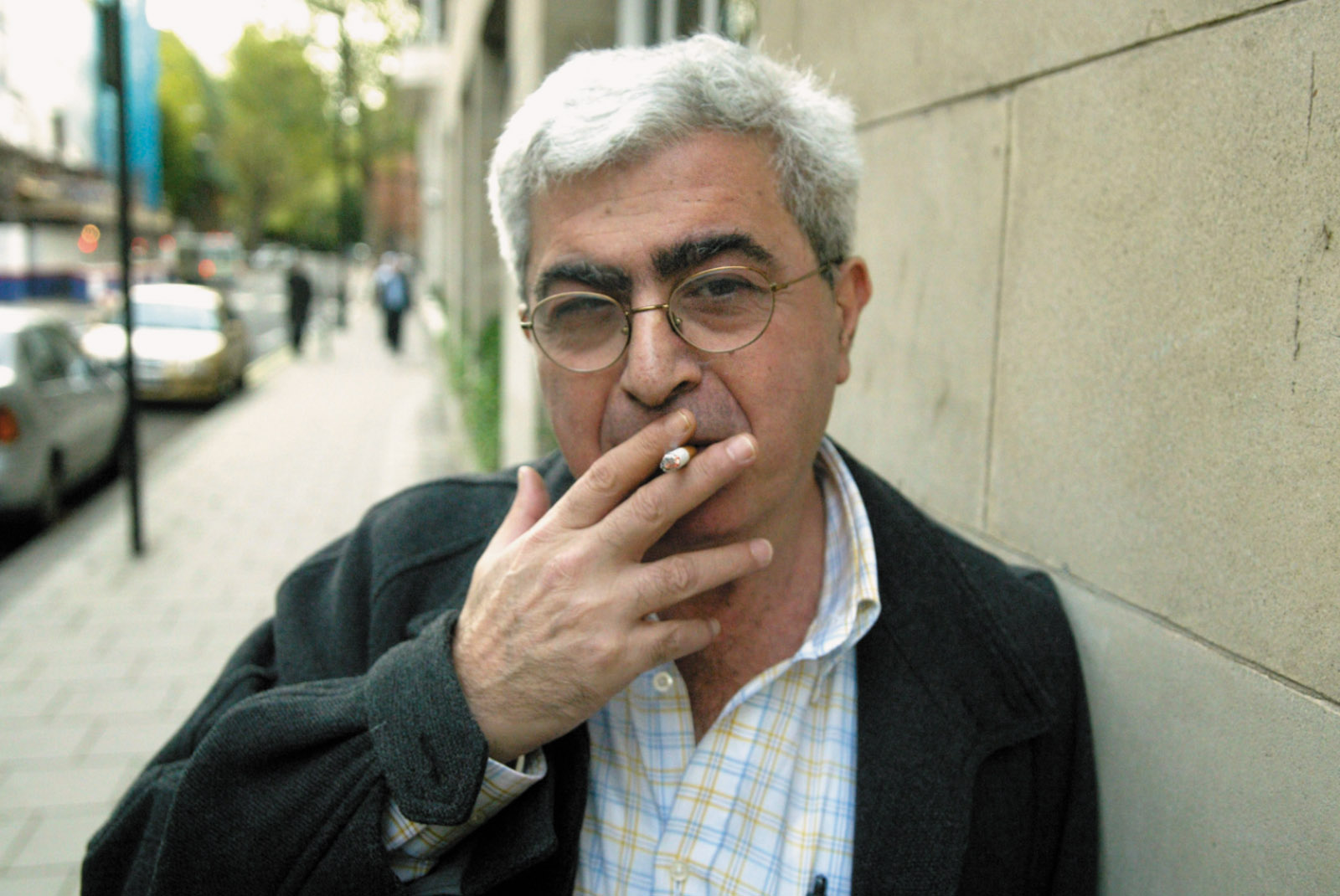

No Lebanese intellectual has been more vociferous than Khoury in asserting the claims of collective memory. From 1993 to 2009, he edited the cultural supplement of the daily newspaper al-Nahar, which he made into a tribune for revealing the imposed amnesia of the postwar settlement. He described Solidere’s plans for downtown Beirut as “an exclusive fortress of gated communities policed by private security.” But Khoury’s defense of memory was neither antiquarian nor nostalgic. He believed that the only way for Lebanon to free itself from its history was to face it. Interrogating the past was, he wrote, an effort “to claim the present.”

Khoury was born in East Beirut in 1948 to a Greek Orthodox family. As a student in the late 1960s, he broke ranks with most Lebanese Christians and joined the Palestinian Fatah movement, fighting alongside leftist forces during the civil war (in which he temporarily lost his sight in one eye). He also studied in Paris and wrote a thesis on the conflict between the Druze and Maronite Christians of the 1860s, another Lebanese war that left few documentary traces. Returning to Beirut, Khoury became a critic and an editor for al-Mawaqif, the liveliest journal of the Arab New Left, where the ideas of Mao Zedong, Che Guevara, and Franz Fanon were debated along with the tactics of Palestinian fedayeen.

It was also in the mid-1970s that Khoury began to write a distinctive sort of fiction, combining techniques from the Arabic oral tradition with an aggressively fragmented narrative. The result is a kind of postmodern One Thousand and One Nights, with multiple narrators and stories nested within stories that refuse to come to an end. It was a style of writing designed to reflect as well as to expose the fragmentation of Lebanese society during the war. Khoury’s best-known work, Gate of the Sun, published in English translation in 2006, uses the same techniques to retell the patchwork epic of the Palestinian Nakba—the defeat of 1948—yet another historical trauma for which there is little written evidence on the Arab side.

Khoury is now widely regarded as the preeminent novelist writing in Arabic, as well as one of the region’s most incisive critics. His fiction has tackled large historical subjects with a consistently inventive approach to form. And his attention to the rhythms of the oral language has given a new flexibility to literary Arabic. Khoury has not abandoned the novel’s traditional strengths—vivid characters, wit, shrewd psychology—but his work is primarily concerned with the problems of recent Arab history, its ironic reversals and unrealized potential. As he writes in Broken Mirrors, in a playful echo of Scheherazade, “Stories don’t end, they go to sleep.”

Karim Shammas, the rather feckless hero of Broken Mirrors, is a Lebanese doctor who lives in Montpellier with his French wife and children. Like Khoury, Shammas once trained with the Palestinian fedayeen, but was not much of a soldier; he fought without distinction in one early battle of the Lebanese civil war and then retreated to Beirut’s cafés.

Following the assassination of a leftist comrade, Shammas flees to France, where he tries to forget Lebanon. He wants to become “a new man”—a Frenchman, in fact—but discovers he cannot. The novel is set in the spring of 1990, when the peace agreement was already signed but Christian infighting continued in East Beirut, one of the final phases of a conflict that refused to end. Ten years after he left, Shammas finds himself back in Beirut, though he is not sure why, or else he will not say. Like many of Khoury’s characters, he is haunted by the past because he has not yet faced it.

Advertisement

Broken Mirrors is a kaleidoscopic work, adopting different points of view to examine the same incidents, shuttling between past and present, mentioning people and events before the reader knows who or what they are. Although the plot keeps biting its own tail—like Lebanese history, according to Khoury—the book is also full of digressions on topics like the lives of Sri Lankan maids in Beirut and the vernacular language of the Crusader kingdoms. Khoury’s novels aim to instruct as well as to entertain: they are full of historical anecdotes, curious information, and intellectual gossip. “Shammas,” the hero’s patronymic, recalls Anton Shammas—the Palestinian writer and translator of Gate of the Sun into Hebrew—whose novel Arabesques is a similarly tangled meditation on memory, storytelling, and history. (Shammas has for years lived in Michigan.)

The early parts of Broken Mirrors focus on family history, especially Karim’s relation to his father, Nasri, a man who had seduced many women and who dies under mysterious circumstances as the novel opens. The plot initially circles around the questions of how Nasri died and whether Karim—who thinks of his father as “the only real man”—will emerge from his father’s shadow (becoming a new man means, in part, not becoming one’s father). On his return to Beirut he becomes involved in two love affairs and caught up in the memory of several others; all of them end badly. There is a hapless, almost endearing comedy to Karim’s romantic defeats, especially when set against his father’s successes.

Over and again in Khoury’s novels, middle-aged males discover that the codes of Levantine machismo, which once governed behavior on the battlefield as well as in the bedroom, have collapsed. In one episode, Shammas reads the old diary of a fellow militant from the 1970s—a character based on Dalal Mughrabi, the Palestinian commando whose raid into Israeli territory provoked the IDF’s invasion of southern Lebanon in 1978. In the diary he finds that a woman whom he once considered a lover had barely noticed him, and that “he wasn’t the hero of the story.”

Khoury’s generation of Arab intellectuals is deeply marked by its defeats. The primal loss of 1948 repeated itself in 1967 and then echoed through a host of lesser setbacks down to the present. Khoury has argued that the Nakba should be seen not as a discrete event but rather as an ongoing catastrophe. In his fiction, he often links the defeats of his male characters in love and war to their obsession with the past. In Broken Mirrors as well as Gate of the Sun, Khoury’s main characters are failed revolutionaries—intellectuals who are doomed to mull over the causes of their failures. These are men who remember everything and whose preoccupation with history unsuits them in some ways for life in the present. It is typically the women of Khoury’s novels who make the pragmatic choice to forget. As one of Karim’s girlfriends argues, in a passage seemingly aimed at Khoury as much as anyone else:

We have to forget if we are to go on living. This was Beirut’s greatness—it was the opposite of all the other cities of the Levant because it was built on the idea of forgetting and drew its vitality from this fact. But Karim’s suggestion that forgetting was why the civil war had repeated itself several times over during a single century was meaningless too. The war kept repeating itself because they were a small people surrounded by greedy neighbors. They were at the crossroads of a disturbed region incapable of solving its problems. That, not memory, was the reason for the war.

There are many reasons to prefer forgetfulness. In Lebanon, as in the Middle East more generally, memory is often mobilized for sectarian reasons, and it is not clear how one might memorialize the civil war without arousing angry political sentiments. “I hate our way of celebrating death,” says one character in Gate of the Sun, and she means the modern rituals of martyrdom, the posters and defiant funerals that have long been staples of political life in the region.

Advertisement

For Khoury, the problem with such rituals, beyond their sectarian character, is that they celebrate the end of a story—or impose an ending on something still ongoing. “The problem of the revolution is that the men and women who die for it are transformed into posters,” Karim reflects in Broken Mirrors. “They die imagining the poster.” Khoury has had enough of the politics of martyrdom. His fiction tries to keep alive memories of the Lebanese war without recourse to such rituals. For him, the novel is a specifically secular mode of history writing.

This notion of what the novel is and might do is put to the test in the second half of Broken Mirrors, which avoids romantic intrigue and plunges directly into Lebanon’s fractious political past—in particular, the left-wing underground of Tripoli, Lebanon’s second-largest city. Tripoli is where Karim once fought with the fedayeen and learned the basics of Marxist philosophy. It is in that city, once a wealthy port and more recently a flashpoint between poor Sunni and ‘Alawite communities, that Karim finally confronts his own political past. This is also where Khoury does his most urgent writing and where the political stakes of his novel at last become clear.

Tripoli was not a major theater in the Lebanese civil war. This may be one reason why Khoury, with his nose in neglected eras of history, chose to write about it.1 In his account, the story of Tripoli in the 1970s also reflects a crucial transition: the fall of the Arab left and the rise of political Islam. In the early 1970s, a populist, pro-Palestinian movement arose in the working-class neighborhood of Bab al-Tabbaneh. The movement, which came to be called the Popular Resistance, was headed by a baker’s son named ‘Ali ‘Akkawi (in Khoury’s novel he is called Abu Rabia), who dreamed of becoming Lebanon’s Che Guevara and led a peasant revolt against the feudal owners of Tripoli’s hinterland. ‘Akkawi was arrested and died in prison (where, in Khoury’s version, he writes his political testament).

His brother and successor, Khalil ‘Akkawi, was a disciplinarian in the Leninist mold who led the Popular Resistance through the war years. Following the Iranian revolution of 1979, a watershed for both Shiite and Sunni political movements, the Popular Resistance transformed itself into an Islamist group, which remains active today. (Khalil ‘Akkawi was assassinated by the Syrians in 1986.) These characters and events all feature in Broken Mirrors under fictional aliases and with some dates altered. As a writer of historical fiction, Khoury is not interested in set pieces and decisive battles—there are none of these in his novel. He is concerned with the struggle of ideas and the accidents of fate.

In Khoury’s version, the defeat of the secular left is full of ironies. Late in the novel, Karim asks the leader of the Popular Resistance about the movement’s conversion to Islamism. The leader explains that Marxism never had any hold on the street; talking about Islam instead of the working class has allowed his militants to blend in with the people of Bab al-Tabbaneh. “Now, at last, we’re like fish in the sea,” he says, quoting Mao on guerrilla warfare to explain his turn toward religion. But there are also more bitter ironies at work. For all the complexities of his history, Khoury is clear that the destruction of the Arab left was largely the doing of Syria—a courageous argument, in view of the Baathist regime’s history of murdering Lebanese dissidents.

Broken Mirrors is full of reminders of Syrian interference in Lebanon before and during the civil wars, putting down the peasant insurgency of the early 1970s, scotching a possible leftist victory in 1976, assassinating pro-Palestinian leaders like Khalil ‘Akkawi, and facilitating the rise of Islamist groups such as Hezbollah, all before occupying the country in the war’s aftermath. For Khoury, it is the Syrian state, the one that has touted its secular, pan-Arab, and pro-Palestinian credentials longer and louder than any other, that has the longest history of betraying precisely those ideals.

So much of Lebanese political life hinges on questions of historical memory. At the end of Broken Mirrors, Karim Shammas finds himself in possession of two archives: the diaries of the Palestinian militant he thought of as a lover and the prison notebooks of Abu Rabia, the would-be Che. Taken together, these memoirs stand in for the history of the Lebanese left. The Islamists would like to get their hands on them—presumably for revisionist purposes—but Shammas, even though he cannot decide what to do with the papers, refuses to turn them over. His decision to safeguard the archives is, in Khoury’s terms, perhaps his one truly heroic act. It proves Shammas’s devotion to a defeated cause, but also keeps alive the possibility that future historians, or novelists, might one day reawaken these stories from their sleep.

Maroun, the narrator of Rabee Jaber’s novel Confessions, remembers reading Saint Augustine while a student at the American University in Beirut, and in particular the famous passage in Book X of The Confessions about “the fields and vast palaces of memory”:

When I turn to memory, I ask it to bring forth what I want: and some things are produced immediately, some take longer as if they had to be brought out from some more secret place of storage; some pour out in a heap, and while we are actually wanting and looking for something quite different, they hurl themselves upon us in masses as though to say: “May it not be we that you want?”

Still in his early forties, Jaber has published eighteen novels—Confessions is the second to be translated into English2—including long historical fictions and shorter, more oblique works set in contemporary Beirut. Confessions belongs to the latter group. Like Khoury’s fiction, it is preoccupied by the legacy of the civil war as well as the vagaries of memory—in particular, the difficulty of remembering the things one especially wants to recall, memories hidden in “some more secret place of storage,” rather than the trivial ones that pour out in a heap.

“What I’m about to tell you is unlike anything you’ve ever known,” Maroun says in the opening pages of the novel, and his story is certainly strange, though it also has the familiarity of fairy tale. Maroun is a foundling: in 1976, during what is known as the Two-Year War, his family is gunned down on Beirut’s demarcation line, the deadly strip that divided the Christian East from the Muslim West. The four-year-old Maroun is adopted by his parents’ killer, a man whose own young son had recently been kidnapped and murdered. Though his birth family is Muslim, Maroun is raised as a Christian (his new father names him after the founder of the Maronite sect, a fourth-century ascetic). This story, like Saint Augustine’s, is one of conversion—though Maroun’s new faith is forced upon him and he remembers nothing of his previous life.

After this extraordinary beginning, the rest of Maroun’s adolescence, recalled in a series of reveries, is comparatively nondescript. His most vivid memories come from his school days in East Beirut, from Christmas holidays, romantic crushes, and his escape to university. In contrast with Khoury’s fiction, Confessions is focused on personal rather than collective memory, with a lyrical stress on details. In one scene, after a shell drops on his neighborhood, Maroun is told that the local seller of ful, or stewed fava beans, was “splattered all over” the cherry tree outside his shop. This sets off a memory of Maroun’s younger self, eating in the same restaurant:

I loved eating there—I remember that boy dipping a piece of bread into the hot ful submerged in oil, and I remember him lifting that piece from the bowl to his mouth, how he ate onions and fresh mint and chopped tomatoes with the ful, and how he licked his fingers afterward. The ful maker would slice pickled turnips just for me, his fingers always steady against the knife, though they trembled whenever he struck a match to light a cigarette. I remember that boy sitting in the restaurant, and I remember the smoke rising from the cigarette, and I remember the sun casting light on the blooming cherry tree.

The novel is full of such moments, which combine, as in a daydream, a sense of self-detachment with heightened perception. The plenitude of these memories—skillfully rendered in Kareem James Abu-Zeid’s translation—stands in contrast to the absence of any memory prior to Maroun’s abduction. Toward the end of the novel, after digging fruitlessly through newspaper archives at the university library, a friend of Maroun’s asks a judge to look through state records for mention of his parents’ murder. “The judge laughed and said all the records from the war—and especially the Two-Year War—had been burned. They’d been burned or lost or stolen or destroyed.” And so Maroun’s story, for all its peculiarity, begins to feel like an allegory for the stories of so many Lebanese, unable or forbidden to lay hold of their communal past.

But the allegory works in more subtle ways as well. Maroun is not barred from his entire past, just the one that matters most. “Why do I remember all those worthless details while my old name lies buried in oblivion?,” he wonders, and we gradually suspect that Maroun’s fixation on details—the licked fingers and pickled turnips—is symptomatic of a peculiarly Lebanese form of repression. Having lost or destroyed their past, the Lebanese—a proverbially hedonistic people—find themselves stuck in the present, albeit one full of the sensual pleasures Saint Augustine once inveighed against.

In the novel’s last scene, Maroun remembers eating cake at his favorite Beirut patisserie, alone on his birthday. “It was the most delicious cake I’d ever had,” he recounts with almost drugged sincerity. “I ate the whole piece and gathered up the crumbs on the fork and ate them too. I ate the whole piece, and felt happy.” This is how the novel ends—a madeleine with no memory. Instead of confirming Maroun’s sense of a continuous self, stretching from the past into the present, it confines him to a blissful but claustrophobic now. Like its ancient model, Jaber’s Confessions is an indictment of the very pleasures it so convincingly evokes.

For all their bad historical luck, the Lebanese, a small people surrounded by greedy neighbors, have been fortunate in their intellectuals. Jaber and Khoury, along with many others, lived in Beirut throughout its fifteen years of conflict and have refused to forget a war in which 250,000 people were killed and one million were forced out of the country. The Syrian civil war has been at least as deadly and disruptive in less than half the time. It has destroyed any number of cities, including some of the oldest and grandest in the world. One can only hope that when the war ends, if it ever does, there will be some artists and historians left with the courage to sift through the rubble.

-

1

The classic account of this history is Michel Seurat’s essay “Le quartier de Bâb Tebbâné à Tripoli,” in his book Syrie: L’État de barbarie (Paris: Seuil, 1989). Seurat, a French sociologist who sympathized with the Arab left, was kidnapped by the Islamic Jihad Organization (a precursor to Hezbollah) in 1985 and died in captivity. Seurat is a character in Khoury’s novel, where he is called Jean-Pierre Giroux. ↩

-

2

The first was The Mehlis Report (New Directions, 2013), also translated by Kareem James Abu-Zeid, which I reviewed for the NYR Daily, “Chasing Beirut’s Ghosts,” July 20, 2013. ↩