Lucile Vasconcellos Langhanke was born in 1906. “Mary Astor” was born in 1921—that was the name that went up in lights for the first time, at Manhattan’s Rivoli Theater, where, not yet sixteen, she was playing in a short film called The Beggar Maid. Soon her Madonna-like face was spotted in a fan magazine by the great John Barrymore and she was commandeered by him to play his love interest in Beau Brummel—as well as the (temporary) love of his life, and maybe the greatest love of hers. She missed out on the chance to play Mrs. Ahab to his Captain in The Sea Beast, but they were back together in Don Juan, the real first movie to include sound, even if it was only background music. Equally prestigious: she was Dolores de Muro, Douglas Fairbanks’s love object, in Don Q, Son of Zorro.

Astor, after nearly forty feature-length silents, made the transition to talkies, although for a long time they were mostly junkies—Ladies Love Brutes, Sin Ship—and while she showed no extraordinary talent, her astounding beauty and impeccable elocution kept her on the screen, and in the chips, until better roles started coming her way: with Ann Harding in the first version of Holiday; with Clark Gable and Jean Harlow in Red Dust. Then, in 1936, after a series of calamities like The Case of the Howling Dog and Red Hot Tires, she was featured in her finest role to date: as the noble Edith Cortright, together with Ruth Chatterton and Walter Huston, in William Wyler’s Dodsworth. It was being filmed while she was also featuring in the greatest Hollywood scandal of the decade: the trial for custody of her daughter, which lasted for weeks and had to be conducted at night, since you couldn’t expect a major studio to shut down filming during the day for a mere court case.

Among the movies to come: The Prisoner of Zenda, Midnight (she’s married, ritzily, to Barrymore), Brigham Young (she’s the great man’s first wife), The Great Lie with Bette Davis for which she won the supporting-actress Oscar for playing a selfish concert pianist with a glamorous up-sweep hairdo who gives her baby away for the sake of her career. Then her greatest role—as the ultra-noir Brigid O’Shaughnessy in The Maltese Falcon—and on to the man-hungry “Princess” who ends up with Joel McCrea’s identical twin in Preston Sturges’s glorious The Palm Beach Story, then soaked to the skin (along with Dorothy Lamour and Jon Hall) in John Ford’s The Hurricane.

And then in 1944, at the age of thirty-eight—as she recounts dolefully in her two excellent memoirs, My Story and A Life on Film—she begins a long string of mothers: first (and best), Judy Garland’s in Meet Me in St. Louis; then Gloria Grahame’s, Dorothy McGuire’s, Elizabeth Taylor’s, Esther Williams’s, Janet Leigh’s; then Taylor and Leigh’s again, plus Margaret O’Brien and June Allyson’s, as Marmee in the 1949 Little Women; and on and on. Mercifully, it was a cameo in Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte—as a murderess, not a mother—that, in 1964, ended her forty-three years on the big screen.

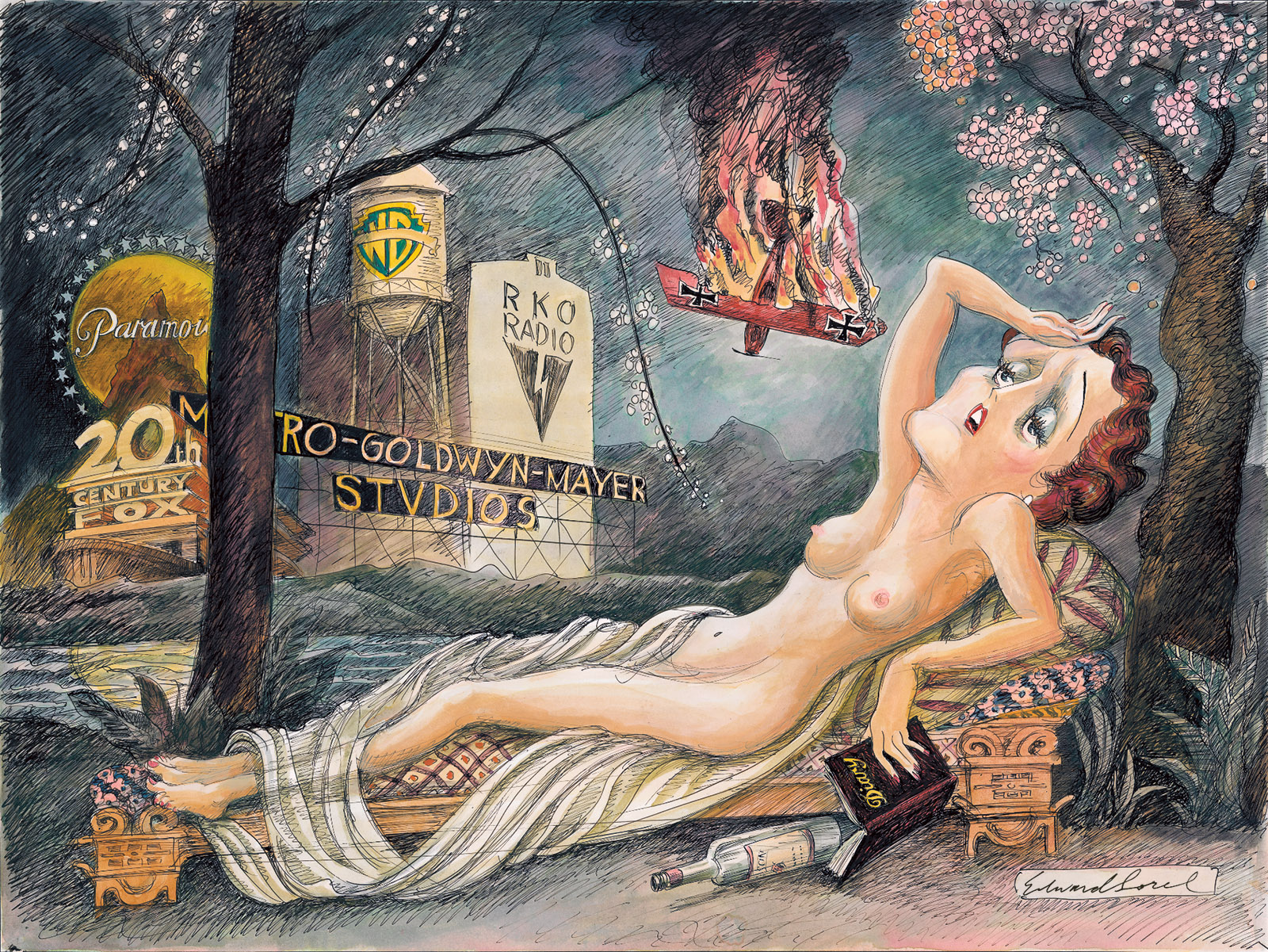

Astor never made a flashy comeback because until her retirement she had never been far away. But now, thirty years after her death, she’s back with a bang, thanks to Edward Sorel’s endearing tribute to her, Mary Astor’s Purple Diary, told in throbbing words and glorious color. (Forget that the notorious diary was written in brown, not purple, ink; the press would have its way.)

The diary—she’d been keeping one since girlhood—purportedly revealed not only details of her torrid affair with the playwright George S. Kaufman but accounts of her affairs with countless other men, many of them top stars of the screen, whose sexual powers she was said to have rated and whose careers (and marriages) would have been destroyed if the news got out in those days of the strict Hays Code. Her ex-husband, whom she was challenging in court, had paid to have the purple pages snatched from her locked desk and had blackmailed her with them to gain total custody of their daughter, Marylyn. But now, in 1936, Mary had decided to fight back at the risk of her own career: mother love came first, a standard Hollywood trope, though in this case real life proved far more turbulent than it does in your standard weeper.

A few pages from the diary were leaked to the press, the more lurid ones forged. The court battle raged on and on, the story dominating the front pages not only of the tabloids but of the Los Angeles and New York Times as Mary, demurely dressed, showed up in court day after day after filming had ended. Eventually, Judge Goodwin (“Goodie”) Knight—who would go on to become governor of California—shut the circus down, sequestered the diaries, and, based on what he believed to be best for four-year-old Marylyn, essentially turned her over to her mother. Kaufman slunk out of town rather than be subpoenaed, scurrying home to New York and his open marriage; Marylyn’s daddy, a fashionable gynecologist, went back to his own multiple affairs, one of them almost certainly a bigamous marriage; and both Dodsworth and Mary’s career flourished. To everyone’s relief, the far greater scandal surrounding the abdication of Edward VIII for “the woman I love” soon replaced the purple diaries as Subject Number One.

Advertisement

How had the Madonna-like Lucile, who had never even been alone with a man until Barrymore and Beau Brummel, turned into such a scarlet woman? Her childhood and youth present an unusual type of abuse. Otto Langhanke, her Prussian father—who had big ideas (raising fancy poultry, writing German textbooks), little common sense, and a lot of bad luck—determined that Lucile was to be the family breadwinner. Perhaps through music? She was force-fed singing lessons. And she was made to practice the piano up to six hours a day, growing so competent that when, decades later, she had to impersonate a concert pianist performing Tchaikovsky’s first piano concerto while a professional pianist played off-camera, her hands on the keyboard were so convincing that even as experienced a musician as José Iturbi was fooled.

But music was not to be the family’s financial salvation. Movies were the great new thing, and Otto decided to cash in on Mary’s beauty. He staked everything on acting lessons, then scraped up the money to get the three Langhankes to New York, where they had no contacts and no road plan. Yet it happened, and at fourteen Mary was before the cameras.

She had had no real childhood, apart from school (which she loved). There were no physical demonstrations of affection. Her father frightened her with his relentless, brutal criticism. She was allowed no friends, no amusements other than reading and wandering alone in nature. She had no money of her own—in her late teens, when she was earning up to $4,000 a week, she was getting by on a weekly five-dollar allowance. Her mother was with her all day, every day, at the studio. Any letters she received were vetted by her parents, and she couldn’t write openly to anyone since she wasn’t allowed even to walk to the corner alone if she wanted to post a letter. There were no parties, no dates, no girlfriends. And no privacy: her bedroom door had to be left open, even at night. Meanwhile, her father made all her deals with the studios she worked for and spent all the money she earned.

But even downtrodden victims can turn on tyrants, and eventually, urged by Barrymore to assert herself, she escaped from her bedroom late one night, climbing down a tree and walking to a nearby hotel. She was nineteen.

No wonder that when this all-work, no-play girl started playing, she played hard. But to get fully away from her parents, she needed to marry, and at twenty-one she married Kenneth Hawks, younger brother of director Howard Hawks. They shared tastes and interests but not sex—every night on their honeymoon he kissed her chastely on the forehead and retired to his own bed. Although they were happy with each other in other ways, their sexual life remained close to nil, and Mary, whose needs had proved to be considerable, began an affair with a Fox executive, got pregnant, and had an abortion. Meanwhile, Ken’s health was deteriorating, not helped by being informed of Mary’s affair—by her mother. In 1930, after two years of marriage, sweet, sensitive Ken died in a plane crash while directing aerial scenes for a movie.

She had loved him, but life goes on, and Mary went on to marry Dr. Franklyn Thorpe, who fathered Marylyn and with whom she was to battle so fiercely in court. The great romance with George Kaufman—she was really crazy about him—ended abruptly when he ran home to Mrs. Kaufman and Broadway, but there were to be many other men, two more marriages, and one more child. Even so, after the scandal died down Mary and Thorpe stayed on good enough terms that for a number of years he remained her principal physician; there was even brief talk of remarriage. As for Marylyn and her father, to whom she was never very close, she has reported: “After I married he became our family doctor and delivered all my children. That’s when I saw him.” Well, he may not have been a good father, but he must have been a good doctor.

Advertisement

Through all the turmoil of her private life, Astor was working assiduously to become a better actress. From the beginning she was determined to learn, but there was no one to teach her, once Barrymore was out of her life. He had wanted her to come with him to London to play Ophelia in his famous production of Hamlet and Lady Anne in Richard III, but her father nixed it: “it was ‘impractical.’” “Of course it was,” she would remark; “no money in it.” Earlier, Otto had ruined her chance to work with D.W. Griffith, an opportunity her friend Lillian Gish had provided. After Griffith turned her down, Lillian explained that he had taken one look at Daddy, and that was enough. “The man is a walking cash register,” Griffith said. “I would never have any freedom to develop the girl.”

No one developed her. She was beautiful, she was likable, she was tractable, even though, as she was to say, half the time she didn’t know what she was doing. And she was in constant demand, for movies she despised. As she would one day write:

There was never any reality…just real big [troubles] that never happened to anyone—avalanches, suffering at the hands of the Huns, or being shot at or starving to death. And everything always came out right in the end.

No surprise that a young woman of her intelligence would end up saying, “I was never totally involved in movies. I was making someone else’s dream come true. Not mine.”

Yet she went on fine-tuning her skills—or as she put it, “sullenly, dissatisfied and unhappy, I was learning a craft.” So that, looking back years later, she could say, “I am proud of the product I developed and sold for so many years, the product called Mary Astor.”

Along the way she made a remarkably prescient decision about her career. By the mid-1930s she was highly marketable and highly paid—specializing, she would say, in

secretaries, princesses, crooks, the wife of, the girl friend of…. I was “Sally at the door, waiting for him” or “Pretty girl, that secretary of yours; now about our deal with the mining company.” Or (hero to hussy), “Sure, I’m married, but what’s that got to do with us?” and there’s a dissolve to me, rocking a cradle, or knitting little things.

But when she was offered starring contracts—grander roles, more money, less work—she turned them down:

I was afraid of starring, of being too “successful.” It sounds paranoid, but I was practical. Because starring was one hell of a gamble, and I couldn’t afford to gamble. I could go on more or less hiding in feature roles, working consistently and not being responsible for the product. “A Joan Crawford picture,” “a Norma Shearer picture,” “a Ronald Colman picture”: If they were bad, it was their fault; they were box-office magic or box-office poison. Once you reached their level, you had to stay at the top, for where else could you go except down? I really wanted to stick around, to feel secure. And I did, and I was.

Ed Sorel discovered Mary Astor in 1965, the year after she made her final film. Stripping layers of linoleum from the floor of the kitchen in an apartment he had just moved into, he came upon old newspapers reporting the purple diary scandal. He was hooked. He was besotted. And he remained so until, just over half a century later, he was ready to give us Mary Astor’s Purple Diary. It’s a love letter, which means it’s a fan’s letter. And why not? If you love a movie star, you’re a fan.

It’s also a love letter to “the movies,” and a love letter from Sorel to himself as a kid and a young man from a poor working-class family in the Bronx. His father was tough—violently opposed to his pursuing art as a career—but so was his mother, who was certain he was talented and fully supported his passion for drawing. Like Mary he changed his name, a further distancing from his father, but while Mary was rechristened by her studio, Ed himself chose “Sorel” to replace “Schwartz” because of his sympathy for Julien Sorel, the doomed hero of Stendhal’s The Red and the Black. Talk about romantic! Naturally, Eddie Schwartz Sorel would fall in love with a onetime movie star.

Sorel had a slow start as an artist/illustrator/caricaturist. Again and again, in various books and catalogs, he is self-deprecatory about his natural abilities, and he’s more or less right: his early drawing, often stiff and crude, barely suggests the triumphs to come. But the wit and intelligence were evident from the start, and the political passion. He was part of the generation of Milton Glaser (best man at his first wedding), Seymour Chwast, David Levine, and Tomi Ungerer, and he went on to work for left-wing venues like Ramparts, Monocle, The Village Voice, The Nation, as well as The New Yorker, Esquire, Atlantic Monthly, Time, New York, and many others, including Penthouse (“The only mass magazine that allowed me to do anti-clerical cartoons”). Cardinal Spellman was a particularly rich target.

And then there was Nixon, the richest and ripest target of all. The only cover Sorel ever did for Screw was one he knew no other magazine would publish: a caricature of Nixon’s great friend Bebe Rebozo listening to a tape unspool, with a voice saying, “Oh! Oh! That feels so good…deeper, Bebe, deeper…ohhhh! OH! BEBE! YOU’RE SO BIG!!” And another voice replying, “Thank you, Mr. President.”

Yet in a series of children’s books he reveals a tender side of his nature, and a deep nostalgia for childhood. Perhaps the most suggestive of them, published in 2000, is The Saturday Kid, whose young hero, Leo, closely resembles the young Ed, sharing with him a love of old movies and old movie palaces. Leo triumphs as a boy violinist, is filmed meeting the mayor, and prevails over the bullying classmate who’s been tormenting him. It’s “dreams of glory” time. Sorel may have been a slow starter, but he was never short on ambition. And like his heroine, Mary Astor, he never stopped improving as an artist, slaving at his drawing until he was in sure command of his pen.

He reached a peak in the art he created for First Encounters, a series of actual “memorable meetings” for which his beloved second wife, Nancy Caldwell Sorel, wrote the text: Henry James meets Rupert Brooke; Sarah Bernhardt meets Thomas Edison; Alexander Fleming meets Marlene Dietrich; Willie Mays meets Leo Durocher…. You don’t want to miss any of them. This is Max Beerbohm turf, and the Sorels don’t suffer by comparison.

Mary Astor’s Purple Diary goes even further, because it’s inspired by love as well as nostalgia. There Mary is: gloriously naked on the endpapers; enraptured by Barrymore, their prominent chins ecstatically dueling; noble and composed while under assault in the courtroom; facing down Irving Thalberg; canoodling with Kaufman in a Central Park horse and buggy.

She may not have wanted to be a star, but Sorel has made her one today, while so many of the supernovas of her time have vanished away.

Sorel’s natural territory is movie-star glamour. For Astor’s real history you have to read My Story—a book that her priest/therapist had suggested she write and that became a considerable best seller when it was published in 1959. Her third and fourth marriages had failed. Her career had dwindled. She had a full hysterectomy. A long, painful relationship was petering out. Her parents—finally—died; she had gone on modestly supporting them. And after her MGM contract ended she had no steady income; in fact, she was broke. “The market refused to deliver or even sell me any food until I paid something on the bill of about seven hundred dollars.”

Friends brought her food, the Motion Picture Relief Fund helped out, she got a scattering of jobs. And her inner strength began to manifest itself. Slowly she found lucrative work in television, where her name and her professionalism prevailed as she gamely mastered a new medium. She did a few shows, including a tour of George Bernard Shaw’s Don Juan in Hell. And she went on writing. Her first novel, The Incredible Charlie Carewe—about a rich, charismatic psychopath—is amazingly assured: derivative, yes, but solid commercial fiction that deserved its commercial success. (Her lifelong passion for reading had paid off.) Other novels followed, as well as her other successful memoir, A Life on Film, this one focused on her movies.

Through these ups and downs two things remained constant: her heavy drinking and her search for spiritual and/or psychological succor. It took years before she could acknowledge that she was an alcoholic and learn to deal with this crippling disease, and it took years before she could feel that through her conversion to Catholicism, she had found a sound relationship with God. It also took years for her to come to terms with her grown daughter, Marylyn, and the son, Tono, she had had by her third marriage. What she never became with her children was close.

To find out what happened to Mary Astor in her later years, we have to go to another new book, which, strangely enough, has appeared at the same moment as Sorel’s. This one, by Joseph Egan, is called The Purple Diaries, and for the most part it retells the life as we know it from Mary herself, only with far more detail from the trial records and considerable quotation from the press coverage. (Huge headline in the Daily News: “FILM STAR DARES ‘RUIN’ FOR CHILD.”) All this will be a treat for completists, of whom I am not one.

But over the decade he spent working on this book, Egan came to know and befriend Marylyn, now in her eighties, a mother of four with forty-three grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Mary, we learn from Marylyn, was a responsible mother, but like her own parents, not a demonstrative one. She was determined to raise Marylyn simply and strictly, with strong values and “no undue pampering.” As Egan puts it, “Raised by an inflexible tyrannical father, as a mother, Astor was also inflexible,” one who “needed to have the final say on everything.” Marylyn had some good times with her, but Mom was mostly off at work, and servants substituted. Then she spent years at boarding school—a relief. (Her younger half-brother, Tono, whom she adored, spent years at military school.) At eighteen, she married—a not very happy marriage that nevertheless lasted fifty-seven years: no four husbands for Marylyn. And no children raised coolly at a distance.

There’s a very long interview between Marylyn and Egan that can be found online (TheMaryAstorCollection.com), and from which he distills the mother/daughter relationship and the story of Mary’s final decades. She went back to her drinking. She drifted away from her Catholicism. For years she lived in a private cottage at the Motion Picture Country Home, taking her meals by herself—she was happiest as a loner. She went on writing, and occasionally made public appearances—after all, she was an articulate survivor of Hollywood’s “golden” period—but she wasn’t really interested in either Marylyn’s life or her children. Marylyn and her husband only rarely made the three-hour drive to see her, nor were their meetings comfortable.

Yet Marylyn loved her mother, and Mary loved her, to the extent that she was capable of loving. What she couldn’t be was nurturing. Or approving. What Marylyn had to deal with, Egan writes, “was a mother who believed there was something wrong with her daughter, who was a constant disappointment to her mother.” In other words, Mary behaved to her daughter the way Otto had behaved to her.

Throughout Mary’s career, she always preferred unsympathetic roles, the sleazier the better: a moll here, a prostitute there, the selfish mother of The Great Lie, the killer Brigid O’Shaughnessy in The Maltese Falcon, the tough, domineering Fritzi Haller of Desert Fury, owner of a gambling club always ready for a fight. “I needed a target,” Astor wrote about this role in A Life on Film; “I needed to fight with somebody.” Fritzi, said Marylyn, was the part that most closely resembled Mary in real life. “Desert Fury was really her.”

The last time the two women met was four months before Mary’s death, at eighty-one, in 1987. When “I told her I had missed her,” Marylyn said, “she told me ‘not to get too sentimental’ about it. I’d had it…and I asked her why she would never let me love her like I wanted to…. Mom looked at me for a few seconds as only she could and then looked at me again, and just told me, ‘GO.’ …I never saw her alive again.”

Yet long afterward Marylyn could say, “Warts and all I still wouldn’t have changed her for anyone else. She was the only mother I had. She was the best mother I had.” Not a ringing endorsement, but Marylyn emerged more or less intact from her childhood, and has had a good life. And so did Tono. Mary Astor may not have been nurturing, but she was reliable and she had rigorous standards. Somehow her kids survived and prevailed.

Ed Sorel doesn’t tell us about these later years—the Mary Astor he cherishes and celebrates is written in his heart in purple ink. But then he isn’t Mary’s daughter.