Some of us suddenly find ourselves very pleased that the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm is closed for refurbishing. It has resulted in the museum sending to the Morgan Library and Museum an unusually good loan show of paintings and drawings. Everything we see was collected, though not always for himself, by Count Carl Gustaf Tessin, a Swede whose lifetime covered much of the eighteenth century—he died in 1770 at seventy-four—and whose involvement with art gives us, with the help of the organizers of the current exhibition, a stimulating way to take in what might be called classic European old master art.

Tessin was, among other things, a politician, a serious cataloguer of his collections, a government official, and a diplomat. He was his country’s ambassador to France between 1739 and 1742, and he became a link between Sweden’s royal family and the art world of the time. That meant Paris, which Tessin had first visited at age nineteen and may have considered his second home. With his expertise, he arranged for the purchase of pictures for the collection of his country’s prince and princess royal and later for its queen. The selection of his purchases for himself and others goes in two almost equally absorbing directions. The drawings, which range from the 1400s through Tessin’s day, are replete with masterworks and give us additionally a window on the art market of that day.

The possibly richer half of the exhibition is about painting, specifically Jean-Siméon Chardin and to a lesser extent François Boucher, two of the foremost artists of the years when Tessin was in and out of Paris. For some commentators, one of the Bouchers on view, The Triumph of Venus, is a candidate for being the painter’s greatest single work. One of the Chardins here, The Morning Toilette, has likewise been thought a high point for this artist. As it happens, both were painted around 1740, and each was commissioned by Tessin.

But just as significantly, there are four other paintings on view by Chardin (1699–1779) of the same type as The Morning Toilette. Generally referred to as genre pictures, they are small tableaux of people caught up in their daily existence. They are a kind of work that Chardin, somewhat like his Dutch predecessors Vermeer and Gerard ter Borch (and like few other artists from any era), elevated to a level where there can be such an organic, breathing unity between the quietly dramatic spirit of the scene, the fresh, convincing, and unillustrational way the figures embody this spirit, and the limpid yet sensuous painting of the smallest detail, as to seem miraculous. Seeing five of these Chardins on a wall at the Morgan—I do not think there are works of comparable strength by the artist in New York museums—one is hard pressed to say whether Tessin’s finer job was getting the Chardins or the drawings to Sweden.

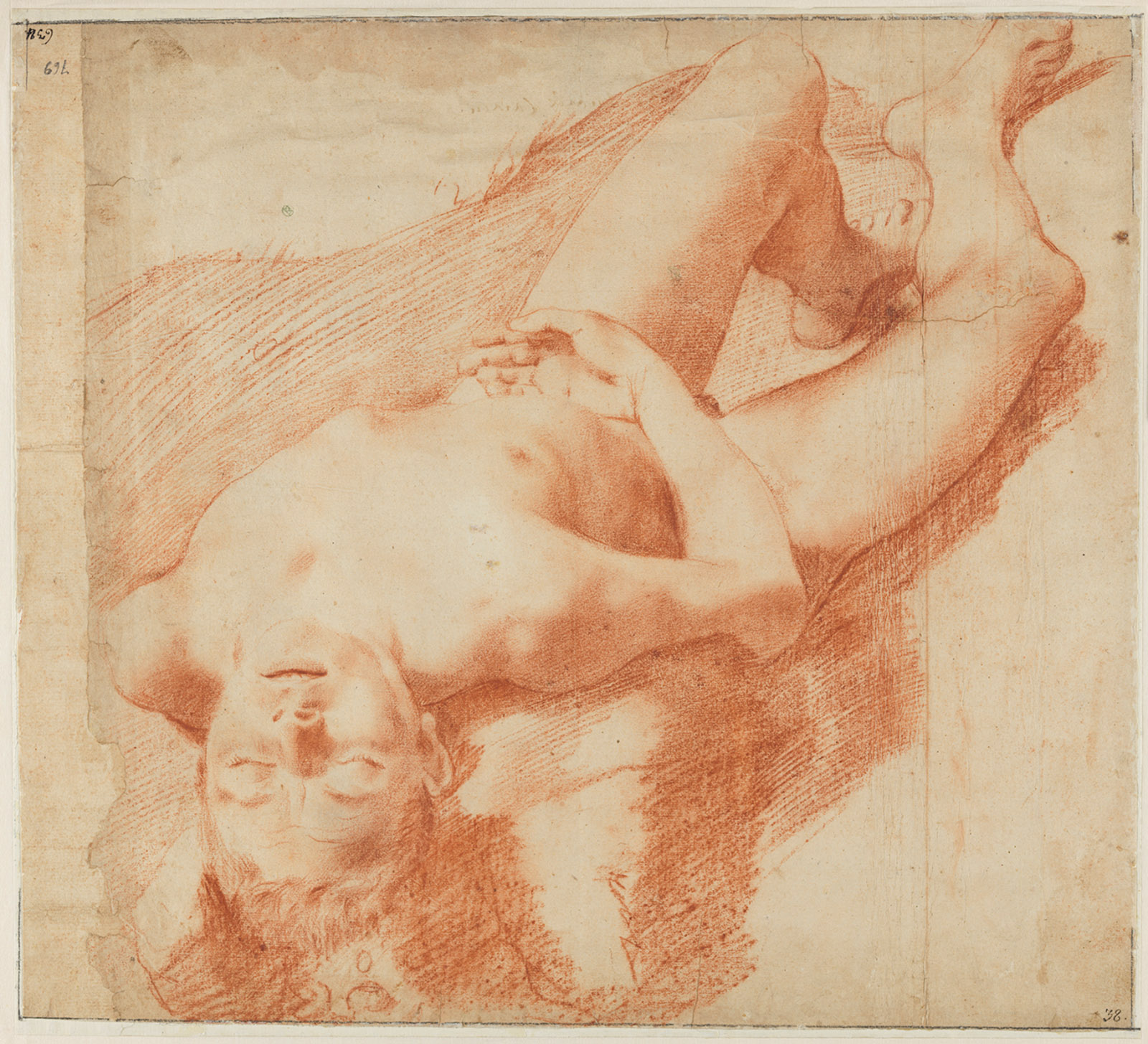

The most striking aspect of the drawings, at least as they have been selected, is how fully for Tessin the formal quality of the works, and not their subject matter, appears to have been what mattered. Among the stand-outs is Jacques Callot’s spectacularly intricate The Temptation of Saint Anthony, in which, industriously abetted by dragons and monsters, the world is, simply put, going to hell; the group of Rembrandts, which made me, at least, realize how fully drawing for him was a trial run and how little he could care for a unified finish; and a dynamic red chalk work by Annibale Carracci of a young nude male model, resting on his back and viewed from above. His head, which is seen upside down and practically falling out of the bottom of the picture, hardly registers as a face. But when you look at the work in the catalog and turn the page around, a specific person is there before you.

The portraits, however, are the works that make this group of drawings sing. It is a great surprise to see, a few steps from each other, large and unfussily direct drawings of people by Albrecht Dürer, Lucas van Leyden, Peter Paul Rubens, and Anthony van Dyck—artists whom we practically take for granted and yet who might almost be discoveries in drawings that will probably be unfamiliar to most viewers. These strong works on paper are backed up by incisive drawings of people by artists whose names may be known but whose work in general remains unclear: Ghirlandaio, Antoine Coypel, Hendrick Goltzius, Guercino, Federico Zuccaro, Jan de Bray, and, totally new to me, Claude Mellan.

Bringing all the drawings on hand to a kind of conclusion, in that they seem the most forward-looking and informal of the displays, are sheets by Antoine Watteau, who was one of the first artists Tessin met when he came to Paris as a youth. The Watteau drawings here are examples of a type of study in which the same or different faces, and expressions, are set one after another on the same page—studies he did more beautifully than almost any artist of any period.

Advertisement

There may be viewers for whom the paintings by François Boucher will be the high point of the show. They are among the larger works on hand, and a detail from Boucher’s Venus forms the show’s poster and the cover of its excellent catalog. In this painter’s highly artificial world, however, waves, billowing fabrics, trees, garments, and grasses all seem crinkly, weightless, and slightly metallic, while his figures, whether dressed for a family tea in the parlor or nude and decorously mythological, seem merely pleasant. The artist, in other words, is an acquired taste.

The antithesis of Boucher is Chardin. He was in many ways the antithesis of most French artists of the eighteenth century. He was one of the few who did not study at the Academy, and in the gentle and meditative mood of his pictures, and in his lack of interest, as a painter, in mythology or the diversions of social life—and in the often softly glowing tones of his paintings, and the creamily thick and brushy ways he, at times, applied paint—he was largely his own man. Besides his genre pictures, which often show women and children and date from the 1730s and early 1740s, he made still lifes, which occupied him on and off throughout his career and are generally of fruit and vegetables.

Sometimes visited by an inspecting cat, his still-life scenes might also show a slab of salmon, a copper cistern, or bottles and flasks. (His work in general is best seen in the sensitive reproductions in the catalog of the Chardin retrospective of 1999–2000, which came to the Metropolitan Museum.) In his early years he often painted freshly killed rabbits, a bit of blood visible on their fur, seen before being readied for cooking. The sixth, and final, Chardin painting in the Morgan’s show is of a dead rabbit, hanging beside a copper pot.

It is possible that Chardin consciously sought to redo aspects of earlier Dutch painting that was about everyday life, or perhaps he was aware of a new feeling for “natural appearances” noted in the art criticism of the time. But he was the opposite of an artist with a program. He was an intuitive, not an intellectual, painter. He was not a learned man, and the few comments associated with him tend, as we would expect, to be about the necessity of hard, steady, and unhackneyed looking at the object or person before his eyes. He was known to take an unusually long time to complete his paintings, and, also notable for his era, neither to use preparatory drawings nor welcome having people about when he painted.

None of this meant that he was opposed to the mainstream attitudes of his day. He was admitted to the Academy and eventually made its treasurer, and he held the position of hanging works at the Salon. His paintings were in demand in all quarters, including more than one royal court. His sole recorded trip outside Paris was to Versailles to present two pictures to Louis XV. Yet Chardin clearly brought a singular awareness to French art. He came from the realm of high-end artisans. His father and a brother were master cabinetmakers whose products included billiard tables for the well-to-do, and Chardin was a bit like them in the sense that in his genre scenes he often shows people in service—and implies the people they work for—and his younger characters tend to play games.

Although the social milieu of Chardin’s scenes is probably not immediately apparent to viewers today, the scholar Colin B. Bailey, a principal author of the current catalog and an authority on eighteenth-century French art (and the director of the Morgan), writes that the painter’s settings were “privileged” and “aristocratic”—not bourgeois, as had been thought. Bailey’s judgment feels accurate and is tremendously clarifying. We might be viewing the life of a grand Parisian residence, one in which the owners, or parents, are not presently at home. Here the house is often seen in its plainer workrooms and pantries downstairs, where Chardin’s children would more likely be found and where his still lifes, though they were conceived independently of the genre pictures, would have their natural settings.

In earlier commentaries, Chardin’s women were often assumed to be the mothers of the children we see. The word “mother” is in the title of a work, and in The Washerwoman, one of the paintings at the Morgan, the woman at the tub, who turns from her washing for a second to look elsewhere—her lovely wide-cheeked face is that of a person we could see on a street today—is possibly the mother of the little boy who sits close by. (We are not sure if we are most taken with his exquisitely painted clothes, the child’s chair he sits on, or the way the bubble he is blowing reflects the rich colors of the nearby cat.) Yet The Washerwoman is one of Chardin’s earliest genre pictures, and as he developed these scenes the children become slightly older than the washerwoman’s boy and more the equal of the adults.

Advertisement

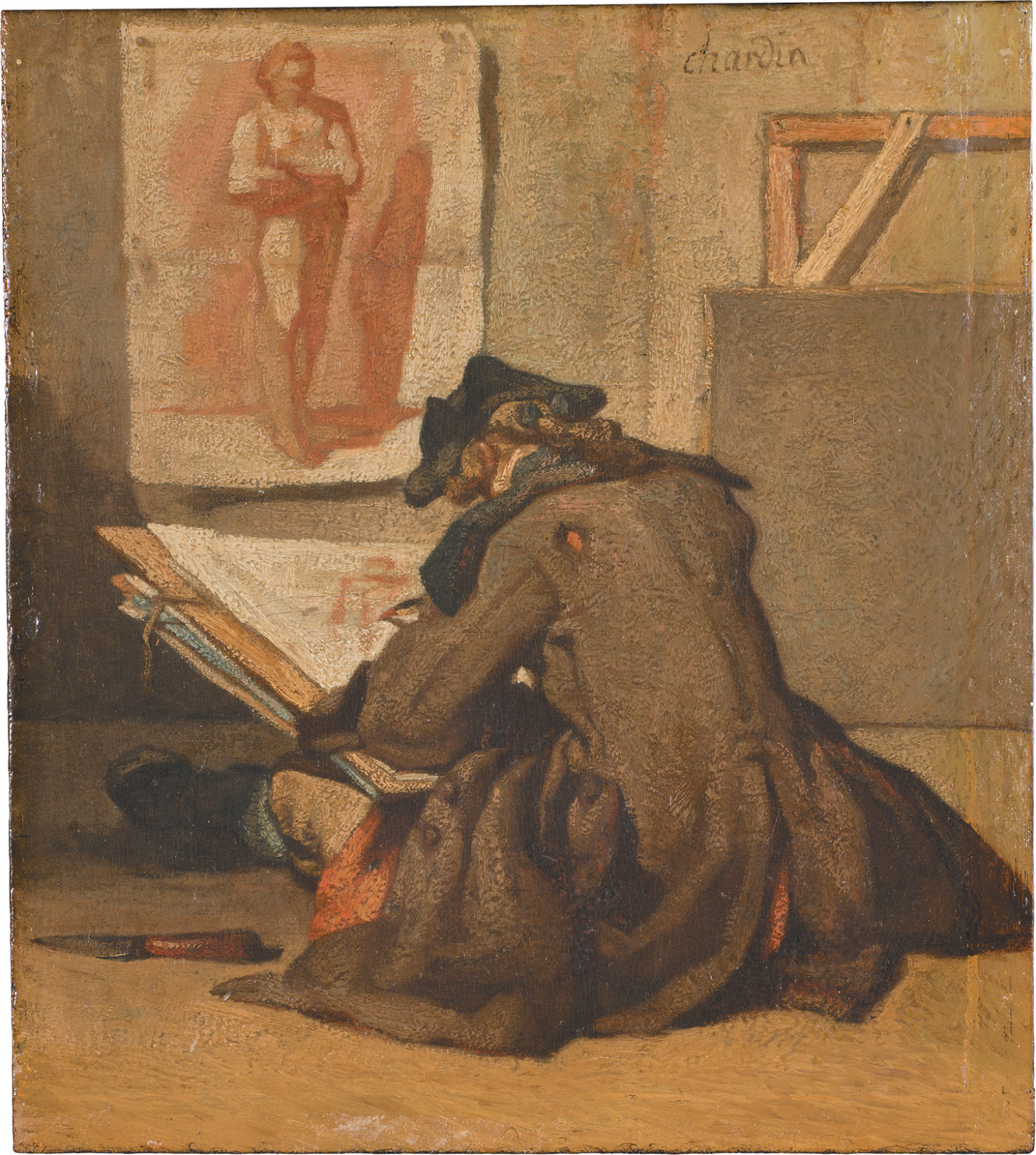

Tessin remarked that the painter’s strength was with “governesses and children,” and it is probably a governess who attends to the young girl in The Morning Toilette, the latest in date of these genre paintings from Sweden. More conclusively, Chardin’s women, whatever position they hold, are more deferential to these children than their mothers would be. Chardin also painted young people on their own. The one such picture in the current show, Young Student Drawing, in which the student is seen from the rear, sitting on the floor, dressed in an overcoat and hat to keep warm, his portfolio somehow balanced before him, is both one of the sweetest and one of the most striking images of an artist ever made. But the painting is anomalous for Chardin. The young people he generally presented are members of his Parisian households.

They are most often found entertaining themselves. They might be building a house of cards, getting ready to play (or having just played) badminton, or blowing bubbles. Taken along with the scenes of boys or girls with servants or their tenders, these images suggest a particular and full world: of children and adolescents who, in settings of some affluence, are being cared for yet are also independent. We can feel we look at the original, and innocent, versions of what, in The Turn of the Screw or in Graham Greene and Carol Reed’s movie The Fallen Idol, become situations rife with secrets and anxiety.

Writers on Chardin over the years—among them Pierre Rosenberg, the foremost Chardin scholar—have noted that audiences now prefer the still lifes over his interiors with figures. My own experience at the large Chardin retrospective of 1979, which came to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (and was the first comprehensive gathering of his work ever), was that his small paintings of grown-ups and children together were his transfixing pictures. I felt this again at the equally extensive Chardin retrospective at the Met in 2000. His still lifes certainly include marvelous and much-heralded paintings. Up until very recently, the only still life in the Frick Collection, for instance, was a painting of plums, a bottle, and cucumbers by Chardin; and, along with somewhat ominous paintings primarily of foodstuffs by the Spanish painter Luis Melén-dez, who was about a generation younger than the Frenchman, Chardin’s examples are among the few such works of the eighteenth century that continue to talk to us strongly.

Chardin gave still lifes a needed realism; he removed the set-apart, showcase quality, with gleaming light, that made most earlier examples feel brittle and airless. But after seeing a number of these paintings a sameness sets in. The deeper issue is that the still lifes rarely have the formal and psychological tension that Chardin can get in his scenes with people. Painting people, he had the chance to use good amounts of the color white, often for clothes, at which he is hardly surpassed. Painting figures, he tended to make his pictures small and to get every aspect of the space surrounding his characters to be felt as a kind of taut frame. These paintings show Chardin, moreover, to have been at times an affecting and canny dramatist.

What gives the five genre scenes from Tessin’s collections an extra allure is that they show how Chardin developed this kind of picture. He initially worked with lusciously thick paint, making every item—the art student’s portfolio, the little boy’s bubble—seem as if it were a self-contained shape that had been dropped into place. The result resembles a cross between food (these works make your mouth water) and, as has been said, marquetry (his father and brother may have felt he was saluting the family line). When, some years later, Chardin made The Morning Toilette, he painted in a less emphatic, more distanced and powdery—but no less remarkable—fashion. Everything in this picture revolves around the way the girl turns to her side, to look at herself in a mirror, as the governess arranges a pin in her hair. Have tentativeness and self-assurance ever been so perfectly conjoined?

Tessin kept the painting in the bedroom. He may have done so because a small, intimate work might have been lost in large public rooms. Perhaps the very subject called for a private setting. Or perhaps he simply wanted to keep this treasure as close as possible.