In the hands of great poets words do things they don’t for the rest of us. They “reek” “of meaning,” as Elizabeth Bishop wrote about other symbols. Bishop’s greatness is nearly universally agreed on, but her words eschew specialness, increasingly so as her work develops, always in the direction of greater directness and freedom. Bishop seems to want to domesticate out-of-the-ordinary, difficult, uncanny things, to make them part of common experience, even when it proves impossible.

In her poems, the almost nineteenth-century rural landscape of Nova Scotia, where she spent much of her childhood; the sun-bleached midday of Key West, where she sojourned as a young adult; and the irreducible otherness of Brazil, where she lived in her forties and fifties, are close-up, vivid, sharply focused. As Randall Jarrell put it early on: “All her poems have written underneath, I have seen it.” But Bishop’s “home-made” realism is as illusionistic as any other art. “When readers praise Bishop’s ordinary everyday diction,” notes Eleanor Cook, who is one of Bishop’s most attentive readers, “they are also praising her sentence structure, grammar and syntax both, as well as a natural speaking rhythm.” All these things, as Cook demonstrates, are the product of intensive, deeply considered labor. “Writing poetry is an unnatural act,” Bishop asserted. “It takes great skill to make it seem natural.”

Borrowing from her sometime mentor Marianne Moore, Bishop wrote that “the three qualities I admire in the poetry I like best are: Accuracy, Spontaneity, Mystery,” and her early work is profuse with descriptive pinning-down. Bishop told her first biographer, Anne Stevenson, that she admired “the beautiful solid case being built up out of his heroic observations” by Charles Darwin, and goes on to say that “what one seems to want in art, in experiencing it, is the same thing that is necessary for its creation, a self-forgetful, perfectly useless concentration.”

This is a positivist approach to poetry—objective, jeweler-like. Cook cites William H. Pritchard’s comment that some of Bishop’s poems—the earlier ones, Cook cautions—risk “overkill” in detail. It’s not a surprise to learn from Megan Marshall, her latest biographer, that at one point she considered attending medical school. Bishop came to view poetry as “a way of thinking with one’s feelings,” but it took her a while to achieve “spontaneity,” the seemingly relaxed tone we think of as quintessentially hers. Her earlier work is not only painstakingly descriptive; its mystery comes by way of modernist difficulty and is tinged with surrealism as she imitates the contraptions of metaphysical poetry.

Bishop’s drastic childhood is essential to her story. Her father died when she was eight months old, in 1911, and her mother suffered a breakdown and was permanently institutionalized five years later. Bishop never saw her again. She was shunted between her father’s more prosperous Massachusetts family and her mother’s more loving one in Nova Scotia. From 1930 to 1934 she attended Vassar College, where her literary vocation took shape. Bishop had been predominantly homosexual since high school. She was a “quietly willful nineteen-year-old,” writes Marshall; one teacher referred to her as “enormously cagey.” “This family life is not for me,” she wrote with typical self-aware, sardonic wit about an alter ego in a teenage poem:

I find it leads to deep depression

And I was born for self expression.

After college, she embarked on a series of romantic relationships with usually wealthier school friends. With the help of a small legacy, she traveled in Europe and lived in New York and Florida, never really settling. She became a heavy drinker, and eventually a lifelong alcoholic.

Bishop’s early work is, indeed, “cagey”—pondered and often hermetic. “The Imaginary Iceberg,” one of her arresting poems of the 1930s, begins:

We’d rather have the iceberg than the ship,

although it meant the end of travel.

Although it stood stock-still like cloudy rock

and all the sea were moving marble.

One can argue that the essential Bishop is all here: a harsh, inimical, northern land—in this case seascape; elemental imagery; motion vs. stasis; pathetic fallacy; sculpted rhythm; chiseled diction. Everything is here, but the poem’s quite possibly erotic import is occluded, obscured. The poet wants to extract a general truth from her symbol, but her poem has difficulty ending. A number of other early texts—“Casabianca,” “The Colder the Air,” “Quai d’Orléans”—are similarly evasive conundrums. Her analyst referred to them as “tight.”

Eventually she would start to make less mannered, less self-protective artifacts. She wrote her analyst, Dr. Ruth Foster, in 1947:

Advertisement

I’ve lost the fear of repeating myself to you…. And I feel that in poetry now there is no reason why I should make such an effort to make each poem an isolated event, that they go on into each other and overlap, etc., and are all really one long poem anyway.1

What is striking here is the scope of the poet’s ambition, her heroic determination, which in fact became crippling, to “regard every single poem as something almost absolutely new.” In Bishop’s characteristic early work, a knowing, eagle-eyed observer thinks intently, with feelings she keeps largely to herself, as she puts aspects of a vast, indifferent reality under the microscope in ever-varying formal experiments, always aiming to go further, if not deeper, into “the interior.” She is unabashedly literary, too. In “The Bight” she writes, “if one were Baudelaire/one could probably hear it [the bight, that is] turning to marimba music.” “The bight is littered with old correspondences,” she adds later, evoking the French poet’s most celebrated declaration of symbolist poetics as if to underline that what we’re reading is far from simple description. She makes it very clear what sandbox she’s playing in.

Her closest friend in art was Robert Lowell, and their correspondence over thirty years is one of the monuments of modern American poetry. Where Lowell is extravagant, enthusiastic, rhetorical, approximate, Bishop is measured, humorous, self-deprecating, reserved yet frank. In one of his first letters, dated August 21, 1947, Lowell, who though several years her junior was ahead of her professionally, writes her about “At the Fishhouses,” a major breakthrough in her work, which closes to ecstatic effect with a description of the preternaturally cold Nova Scotia water:

If you should dip your hand in,

your wrist would ache immediately,

your bones would begin to ache and your hand would burn

as if the water were a transmutation of fire

that feeds on stones and burns with a dark gray flame.

If you tasted it, it would first taste bitter,

then briny, then surely burn your tongue.

It is like what we imagine knowledge to be:

dark, salt, clear, moving, utterly free,

drawn from the cold hard mouth

of the world, derived from the rocky breasts

forever, flowing and drawn, and since

our knowledge is historical, flowing, and flown.

Lowell writes to say

how much I liked your New Yorker fish poem. Perhaps, it’s your best. Anyway I felt very envious in reading it—I’m a fisherman myself, but all my fish became symbols, alas! The description has great splendor, and the human part, tone, etc., is just right. I question a little the word breast in the last four or five lines—a little too much in its context perhaps; but I’m probably wrong.

His praise betrays an anxiety to “place” Bishop, to pin her on the poetic map, as was his competitive habit with his peers. (In 1957, he would describe other poems of hers as “very womanly and wise.”) But the “rocky breasts” Lowell questions are in fact the very heart of the matter of Bishop’s first masterpiece. They are the source of the “bitter dark gray liquid” that Bishop wrote her analyst she had dreamed about drinking from her breast, transmuted here into the sea’s “cold dark deep and absolutely clear” yet burning firewater. She writes her doctor: “Heavens do you suppose I’ve been thinking of alcohol as mother’s milk all this time and that’s why I pour it down my throat at regular intervals?” It is this cold, bitter, dangerous, irresistible liquid, “derived from the rocky breasts/forever,” that for the poet is “what we imagine knowledge to be.”

The association rock-mother-truth is a figuration of implacable reality for Bishop, and rock reappears as such in her late elegy for Lowell, “North Haven” (1978):

The islands haven’t shifted since last summer,

even if I like to pretend they have

—drifting, in a dreamy sort of way,

a little north, a little south or sidewise,

and that they’re free within the blue frontiers of bay.

The habits of flora and fauna—very like those recorded so minutely by her hero Darwin—remain all but unchanged on the island, year on year, except for the inevitable note of evolutionary correction:

Nature repeats herself, or almost does:

repeat, repeat, repeat; revise, revise, revise.

But Lowell, the notorious reworker of his poems, is gone. His manic remaking has fatally hit up against stony necessity, embodied here in Maine’s elemental landscape:

You left North Haven, anchored in its rock,

afloat in mystic blue…And now—you’ve left

for good. You can’t derange, or re-arrange,

your poems again. (But the Sparrows can their song.)

The words won’t change again. Sad friend, you cannot change.

Rock reoccurs, too, in one of the most remarkable of Bishop’s posthumous texts, “Vague Poem (Vaguely Love Poem),” from about 1973:

Advertisement

Rose-rock, unformed, flesh beginning, crystal by crystal,

clear pink breasts and darker, crystalline nipples,

rose-rock, rose-quartz, roses, roses, roses,

exacting roses from the body,

and the even darker, accurate, rose of sex—

Here rock is equated with the “exacting,” “accurate”—that is, inexorable, immutable—rose of the female genitals.

It’s clear from texts like these and from her letters to Foster that Bishop’s understanding of her sexuality was nuanced and largely self-accepting.2 If the public world in which she made her mark was male-dominated, the private affective one she lived in was almost wholly female. Marshall’s book expands our knowledge of Bishop’s early relationships with Margaret Miller, Louise Crane, Marjorie Stevens, Hemingway’s ex-sister-in-law Jinny Pfeiffer, and others. On a visit to Brazil in 1951, she fell ill and was cared for by an acquaintance, the landscape architect Lota de Macedo Soares. They fell in love, and Bishop ended up staying in Brazil for more than fifteen years. The Northern Hemisphere landscapes of her early work, collected in North and South (1946) and A Cold Spring (1955), are countered now by the lushness and wildness of a new continent whose inhabitants have very different mores.

As Bishop lived there, so far from the Anglo-Saxon world she had moved in, her poetry gradually became more experimental, though her representations of her emotional life, as with most homosexual writers of her time, are figured, muted. And the perpetual question of location—“Should we have stayed at home,/wherever that may be?”—remains crucial, as the title of her third book, Questions of Travel (1965), largely written in Brazil, underlines.

Over time the union with Macedo Soares frayed, and Bishop found other lovers. In 1966, she spent a semester teaching in Seattle. The following year, Macedo Soares came to visit her in New York, where she took a fatal overdose of sleeping pills. Bishop’s life in Brazil was over. She began teaching at Harvard in 1970, standing in at first for Lowell. Here she met Alice Methfessel, a spirited young woman who would be the partner of her last years. Marshall’s book is the first to make use of a trove of papers that offers an unusually intimate window into this period, and her focus on them perhaps inevitably brings to the foreground the turmoil in Bishop’s life as she approached old age under the enduring strain of alcoholism.

Marshall also touches on Bishop’s acquaintance in the mid-1970s with Adrienne Rich, a poet a generation younger who was becoming engaged with issues of gender and sexuality that were beginning to agitate American culture, and who respectfully challenged Bishop’s outwardly traditional, ladylike feminism. Bishop had always resented being relegated to what she considered the second-class status of “woman poet,” a category Lowell himself sometimes resorted to, and she steadfastly refused to be included in anthologies of women writers. Men and women “do not write differently,” she insisted. Yet to Rich, who had recently begun to identify as lesbian, and who shared with her the loss of a loved one to suicide, Bishop acknowledged both a desire to write more openly about women’s lives and her own anger at her male peers’ paternalism. “I must have felt the same way many years ago,” she wrote Rich, “but my only method of dealing with it was to refuse to admit it.”

Reviewing Bishop’s Complete Poems, 1927–1979 a decade later, Rich, now a self-described radical feminist, allowed that she had initially been put off—“repelled” is the word she uses—by the “encodings and obscurities” in Bishop’s work, though Rich had not initially connected these to Bishop’s “themes of outsiderhood and marginality.” But “especially given the times and customs of the 1940s and 1950s,” she had come to see Bishop as “remarkably honest and courageous.”

Rich does her level best to honor the “flexibility and sturdiness of [Bishop’s] writing, her lack of self-indulgence, her capacity to write of loss and of time past without pathos,” while her acceptance by “a white, male, and at least ostensibly heterosexual” literary establishment had been based on “her triumphs, her perfections, not…her struggles for self-definition and her sense of difference.” Rich strains more than a bit as she tries to bring her older peer in under the tent of her own activist politics; but her reading of Bishop, with its emphasis on her strategies for getting around if not openly opposing phallocratic domination and her explorations of otherness, has proven influential in Bishop’s extraordinary posthumous rise to preeminence among the poets of her generation.

If Bishop’s late work doesn’t break really new political ground—her conscious gestures in this direction are never as convincing as her letter-perfect evocations of what she knows and sees firsthand—the ten poems in her last book, Geography III (1976), and the few poems that follow it before her death in 1979 arrive at a new plateau of self-possession. As Cook summarizes it, “The sense of constraint in some of her earlier work vanishes, her poetic voice becomes more confident, her generic repertoire increases, and a growing sense of freedom is evident.” I am less taken with the extravagantly praised “One Art” and “In the Waiting Room” than with, say, the more narrative or discursive poems “Crusoe in England,” “The End of March,” “The Moose,” which had languished unfinished for decades, and “Poem,” about the talent for observation she finds she shares across the generations with the creator of a small painting, “a minor family relic,” that she suddenly realizes portrays a place that she too knows:

Our visions coincided—“visions” is

too serious a word—our looks, two looks:

art “copying from life” and life itself,

life and the memory of it so compressed

they’ve turned into each other.

“In the Waiting Room,” by contrast, is a parable of self-recognition (“you are an Elizabeth,/you are one of them”) that springs, significantly, from the young Bishop’s encounter with pictures of “black, naked women” whose “breasts were horrifying” in the pages of National Geographic; the poem reads like an unvarnished schematic experiment. And “One Art,” a modified villanelle written at a moment when Methfessel had decided to leave Bishop and that she described as “pure emotion,” feels motivated by the very “pathos” that Rich praises Bishop’s work for resisting. The obsessively repeated rhymes (master, disaster) and the uncharacteristically fussy diction of the closing quatrain—

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

—betray an anomalous unworked-through desperation.

Against “One Art”’s sentimentalism—a quality that rarely pokes through in Bishop—stands the matter-of-fact acknowledgment of the attractions of self-pity in what many consider her greatest achievement, the crypto-autobiographical “Crusoe in England”:

I often gave way to self-pity….

What’s wrong about self-pity anyway?

With my legs dangling down familiarly

over a crater’s edge, I told myself

“Pity should begin at home.” So the more

pity I felt, the more I felt at home.

What’s most remarkable, perhaps—accurate, spontaneous, and mysterious—in this self-portrait of a world traveler back from a life-changing sojourn elsewhere, “drinking my real tea,/surrounded by uninteresting lumber” and without “my dear Friday,” is the note of truculent humor that humanizes, domesticates, Crusoe’s—and Bishop’s—resignation in the face of ultimate loss. It is the same saving bravery, indeed, that operates so movingly in her letters. Surrounded as she was by a bevy of poets—Berryman, Schwartz, Jarrell, Plath, Sexton, Lowell himself—whose lives were touched and in many cases destroyed by mental illness, and given her own precarious family history, she was, she wrote a friend, “determined that I am one poet who’s going to stay sane till the bitter end.”

Marshall’s book offers a portrait of a human being who often resembles the “finical, awkward” sandpiper of Bishop’s poem of the same name, “in a state of controlled panic…preoccupied…obsessed”; or the “creature divided” of her last poem, the magical “Sonnet,” with its “compass needle/wobbling and wavering,/undecided.” Her Bishop is by turns loving and needy, libidinous and stoical, manipulative and matter-of-fact; and Bishop presented herself in similar terms as she carried out what James Merrill called her “instinctive, modest, lifelong impersonations of an ordinary woman.” But “Sonnet” ends this way:

Freed—the broken

thermometer’s mercury

running away;

and the rainbow-bird

from the narrow bevel

of the empty mirror,

flying wherever

it feels like, gay!3

It is the urge toward freedom, against and in spite of being “caught,” that makes “Sonnet” such a definitive testament of experiential ambivalence. Bishop could imagine another existence—running away, unfettered, gay—if only perhaps in another world.

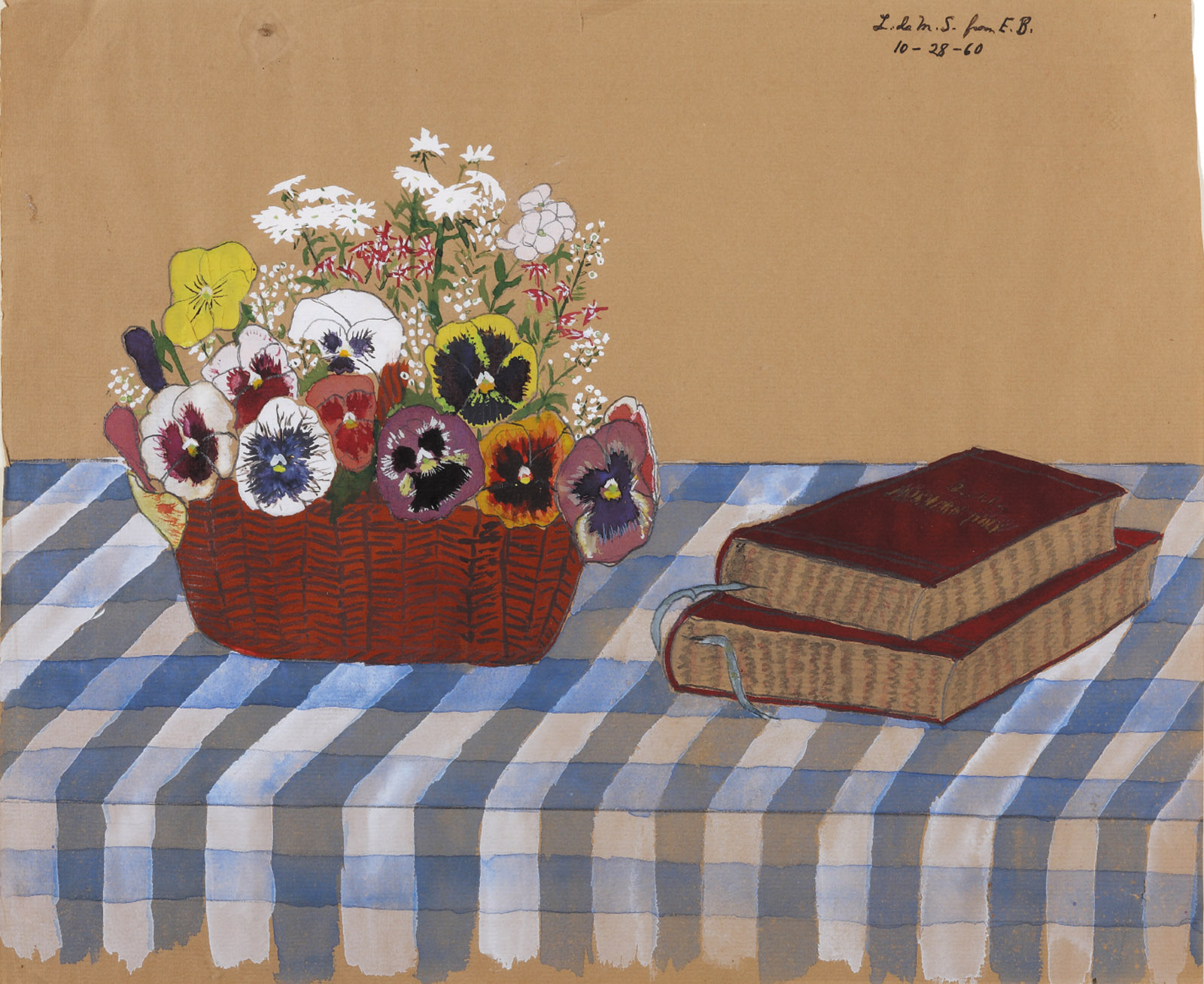

Marshall intersperses her narration of Bishop’s life with chapters about being her student that add little to our understanding of the poet’s life. And her referring to her subject as “Elizabeth” feels a tad cloying, given that Bishop always insisted on addressing her students by their surnames. Surprisingly, there is no mention of her lifelong practice as a gifted Sunday painter—what, I’ve often wondered, do the overemphatic power lines in her townscapes represent, connection or constriction?—or of her remarkable work as a translator.

It would have been instructive, too, to learn from Marshall, as we do from Cook, that Bishop found solace in the writings of the eighteenth-century English divine Sydney Smith, whose letters contained “the only sensible advice” she felt she had ever heard (“Take short views of life,” “Be as busy as you can,” “Live as well as you dare”). She wrote Lowell that she read them over “two or three times a year” for encouragement and couldn’t think of “any more cheering reading.” What Bishop responded to in Smith, no doubt, is the same doughty stoicism that was such an indelible part of her own northern character. It is there in her favorite lines of her own (from “The Bight”), which she wanted incised on her gravestone: “All the untidy activity continues,/awful but cheerful.”

More Bishop books are underway, among them her complete correspondence with Moore and her journals. There will be other biographies, too, and critical interest in her work shows no sign of abating. There is much more to learn about the banked fires that compelled this reticent yet forthright figure who stood at the crossroads of a world of “Closets, closets, and more closets,” as she approvingly put it, and a liberation that has all but dispensed with privacy; and whose own poems evolved from cool metaphysical constructions to crystalline lyrics that give the illusion of utter transparency.

One of the subjects that feel ripe for investigation is what in fact is “womanly,” as Lowell put it, about Bishop’s genius. Pace Bishop, it seems arguable that women and men do write differently—but how, exactly, and what does it signify? What is the gendered dimension of the hard-won wisdom that underlies Bishop’s unique power as a poet and makes the unpredictable yet inexorable trajectory of her work so endlessly absorbing to contemplate? Maybe it has something to do with her “chief complaint against the opposite sex”: that “they don’t see things. They’re always having ideas and theories, and not noticing the detail at hand.”4 Not much escaped Bishop’s unshowy, razor-sharp notice. She stayed true to her original project, too; she almost never repeated herself. Her thinking with her feelings, her clear-eyed, humane sounding of reality—“‘Life’s like that./We know it (also death)’”—kept on evolving, deepening until the very end.

-

1

Bishop’s letters to Foster, dated February 1947 and so far unpublished, are discussed in Lorrie Goldensohn, “Approaching Elizabeth Bishop’s Letters to Ruth Foster,” Yale Review, January 2015. ↩

-

2

See Edgar Allan Poe and the Jukebox: Uncollected Poems, Drafts, and Fragments, edited and annotated by Alice Quinn (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006). ↩

-

3

Bishop told Lloyd Schwartz that she’d wanted to free the word “gay” from its modern-day servitude and restore its “original” meaning. ↩

-

4

She continues: “I have a small theory of my own about this—that women have been confined mostly—and in confinement details count.” ↩