Sir Edmund Walker Collection/Royal Ontario Museum

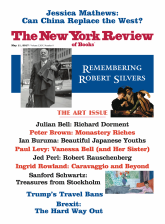

Kitagawa Utamaro: The Young Man’s Dream, from the series Profitable Visions in Daydreams of Glory, circa 1801–1802. In this woodcut, Ian Buruma writes, a wakashu,or ‘beautiful youth,’ is ‘dreaming of sleeping with a famous high-class courtesan (the dream is revealed in a cartoon-like bubble over his head), while a young woman solicitously wraps a jacket around his shoulders lest he catch a cold.’

Lusting after pretty teenage boys was not considered shameful in premodern Japan. Experienced older women did it. Young women did too. Older men indulged in it (as long as the boys were passive sexual partners). Adultery was not permitted, on the other hand, and it was unseemly for grown men to love other grown men. But the love of older men for young boys, a practice called shudo, literally “the way of boy love,” was considered, especially during the eighteenth century, and notably among samurai, to be a mark of erotic discernment.

Ihara Saikaku (1642–1693), the great literary chronicler of the demimonde in Osaka and Kyoto, wrote a famous book called The Great Mirror of Male Love, in which he celebrated shudo:

Even if the woman were a beauty of gentle disposition and the youth a repulsive pug-nosed fellow, it is a sacrilege to speak of female love in the same breath with boy love. A woman’s heart can be likened to the wisteria vine: though bearing lovely blossoms, it is twisted and bent. A youth may have a thorn or two, but he is like the first plum blossom of the new year exuding an indescribable fragrance. The only sensible choice is to dispense with women and turn instead to men.*

There is no evidence that Saikaku himself preferred men to women. The contrary seems to have been true. He adored his wife so much that he decided to become a lay monk after her death. But to Japanese of his time sexual preference was fluid, more a matter of taste than of fixed identity. A cultivated gentleman could fall for the beauty of youths, even as he pursued young women with equal fervor. There were men, of course, who only liked males. They were known as onnagirai, “men who don’t like women.”

So the choice of beautiful youths, or wakashu, as the theme for an exhibition of Edo Period (1603–1868) art was inspired. For it tells us much, not only about the social mores of premodern Japan, but also about its aesthetic values. Shudo was as much a matter of artistic refinement, even connoisseurship, as of erotic fulfillment. A literary expert on this topic, Inagaki Taruho, wrote a famous book, published in 1973, entitled The Aesthetics of Boy Love. He explains, among other things, that only “members of a privileged class can understand the delights of boy love.” Cultivation of this taste demands a certain degree of leisure and sophistication. The difference between boys and girls, he writes, is that girls mature into attractive women, whereas the peculiarly intense beauty of a boy withers as swiftly as the cherry blossom: “Once the youth becomes a young man, and smells of penis, it is all over.”

This is not just the eccentric view of a lecherous old man. Inagaki was seventy-two when he wrote his book. He was simply expressing an ancient Japanese idea of beauty. The cult of the cherry blossom, beauty on the cusp of ripening and then inevitable decay, the melancholy poetry of evanescence, goes back many centuries. It was perverted in the last years of World War II when students from the best universities were sent to their deaths as kamikaze pilots. They were sometimes known as cherry blossoms.

The greatest classic of Japanese literature, Murasaki Shikibu’s Tale of Genji, is a kind of monument to the ideal of young male splendor. Murasaki was an eleventh-century aristocratic lady and not a practitioner of shudo, of course. But it is remarkable how the extraordinary beauty of the young Shining Prince is described more effusively, in more flowery terms, than the charms of the many women and girls he seduced. He was

such an attractive figure that the other men felt a desire to see him as a woman. He was so beautiful that pairing him with the very finest of the ladies at the court would fail to do him justice.

In many prints on display at the Japan Society, the wakashu are almost impossible to distinguish in dress and deportment from the female beauties in the same pictures. An exquisite woodcut by Utamaro, for example, shows an elegant woman gazing up adoringly at a young samurai. Despite his two swords, he looks like a young woman himself. What gives him away as a youth is the shaved spot on the crown of his head between his forelocks and the elaborately arranged hairdo on the back and sides. After coming of age at eighteen or nineteen, the forelocks would be cut off and the pate clean-shaven.

Advertisement

Age in the cult of young beauty is important, but in fact not crucial. Sometimes adult men would adopt the looks and mannerisms of wakashu. In her introduction to the exhibition catalog, Asato Ikeda points out that wakashu “was a gender role—not a fixed biological category—that was performed.” She is quite right to emphasize performance, since the “third gender” was an essential aspect not only of samurai romances, but also of brothel life and theatrical spectacle. The performances of prostitutes and actors were intimately linked in Kabuki. Many erudite critical reviews in the Edo Period assessed the merits of both.

The earliest Kabuki performances occurred in the first years of the seventeenth century, when a female Shinto shrine attendant named O-Kuni staged lewd song and dance numbers on the riverside in Kyoto, often related to stories from the nearby brothel districts. O-Kuni liked to get up in male drag. The female performers were also sexually available for a fee. In an effort to crack down on prostitution, women were banned from the theater in 1629, to be replaced by wakashu actors playing the roles of women or of young boys in romantic trysts with older men. But since they were no less in demand for sexual favors, they were duly banned from the stage in 1652. The wakashu were replaced by men, some of whom specialized in female roles, the onnagata. Many famous onnagata—such as Anegawa Chiyosaburo, shown in a 1735 print by Okumura Toshinobu—started their careers as boy prostitutes.

Cross-dressing has a long tradition in Japan, not just among men, but among women too, ranging from O-Kuni in the seventeenth century to the all-female Takarazuka revue in our own time, whose remarkable renditions of such chestnuts as Gone with the Wind or Madame Butterfly still attract millions of mostly very young female fans. One picture in the show, painted on silk by a nineteenth-century artist named Kaian, portrays five young people dancing, some wearing swords, some with forelocks but no swords. Only one dancer is clearly identifiable as a man. All the others are ambiguous (see illustration on page 30).

Female prostitutes would sometimes pose as wakashu to titillate their clients. In a 1767 print by Harunobu we see two pretty young women, one with a letter in her hand and the other clutching a three-stringed samisen. Some scholars maintain that they are actually male prostitutes.

Many of the prints in the show are of wakashu striking elegant poses, attracting the attention of experienced courtesans. There are some lovely pictures of onnagata, and of the pleasure districts in Edo. One of my favorite woodcuts is by Utamaro, made around 1801, showing a wakashu dreaming of sleeping with a famous high-class courtesan (the dream is revealed in a cartoon-like bubble over his head), while a young woman solicitously wraps a jacket around his shoulders lest he catch a cold (see illustration on page 29).

In some pictures, we see the wakashu seducing women or young girls. But mostly these girlish boys are the objects of desire rather than the initiators. A print from the 1790s, attributed to the Utamaro school, shows an older woman pouncing on a boy who looks quite disconcerted. In erotic prints, known as shunga, the wakashu are often depicted as more feminine than their female partners. A lovely illustration by Kitao Shigemasa from an eighteenth-century storybook shows a young woman stroking a wakashu’s erect penis. She appears to be coaxing him: “Listen to what I’m saying! Here, here!” Whereupon the boy replies: “I just can’t do that kind of thing.” The woman: “Come on! You are such a tease!”

One might easily get the impression from the pictures on display—though less so from the catalog—that the taste for boys was largely a heterosexual affair. There are indeed echoes of the female fascination for androgynous boys in contemporary culture. The cross-dressing stars of the Takarazuka, many of whom by the way are far from straight, are an obvious example (although boys are not exactly their cup of tea). But there is also a remarkable genre of manga, or comic books, read almost exclusively by teenage girls and featuring romances between beautiful young boys. These are not a modern version of shunga. The stories are more like the chaste romantic fantasies of girls who like to dream about boys, but would be frightened of anything carnal. Some Western movie stars and rock singers have had astonishing success in Japan by appealing to the starry-eyed yearning for androgyny. David Bowie was one. So was the Austrian film actor Helmut Berger; he had a huge young female following in Japan long after his fame faded in the West.

Advertisement

Nonetheless, the impression that wakashu were mostly the objects of heterosexual desire in the Edo Period would be quite false. So why are there no shunga of homosexual acts in the exhibition? There are some famous ones, such as Male Love Actors Without Their Make-up, designed by Kitao Shigemasa in the 1770s, of an older man having sex with a young onnagata, while a female attendant splashes cold water on them to cool the senior figure’s ardor. Or Games with Young Men: Fragrant Pillow (1675), by Moronobu, featuring another love scene with a young actor, accompanied by a blind samisen player. The catalog contains some shunga of male couplings, though far fewer than heterosexual ones.

The prints are from a collection in the Royal Ontario Museum. The reason why shunga, especially homoerotic ones, are almost entirely absent from the exhibition is explained by one of the curators in the catalog: “In consideration of the Canadian child pornography law, and in consultation with managers at the museum, I had to make the difficult decision to exclude explicitly sexual images (shunga) of wakashu from the exhibition.” In fact, Canadian law bans

a photographic, film, video or other visual representation, whether or not it was made by electronic or mechanical means,

(i) that shows a person who is or is depicted as being under the age of eighteen years and is engaged in or is depicted as engaged in explicit sexual activity, or

(ii) the dominant characteristic of which is the depiction, for a sexual purpose, of a sexual organ or the anal region of a person under the age of eighteen years….

So caution is probably in order. Still, it is hard to imagine how anyone could be corrupted or encouraged to abuse minors by seeing seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Japanese woodcuts of wakashu and their patrons. In any case, leaving homosexual pictures out, while showing women swooning over or lunging at teenage boys, seriously distorts the history of the third gender. After all, shudo was at the heart of the wakashu aesthetic. It cannot be understood without paying particular attention to boy love.

The romantic ideal of adult men loving young boys had a lot to do with the samurai ethos of the time. As is often the case in warrior castes, women were held in a certain degree of contempt. They were necessary for procreation, of course, and many warriors no doubt found them sexually attractive. But relationships between men were held in far higher esteem. Romantic notions of self-sacrifice, brotherhood, comradeship, and so on were reserved for men. Mutual devotion between older and younger men was the highest form of samurai bonding. In the eighteenth century, when Japan was unified, isolated from much of the rest of the world, and at peace, warrior values had no more practical use. So they became a form of artistry. And that included the cult of the wakashu.

In fact, of course, the taste for boys was not always as pure or refined as Saikaku makes it out to be in his Great Mirror of Male Love. Saikaku takes male romance to extremes. In one story, the older man scoops up water from a river and drinks it, because he has seen his young lover spit in it. In another, a young samurai commits suicide after he tortured his lover to death in a fit of jealousy.

In real life, boy love was usually considerably less romantic. Brothels in Edo, Kyoto, and Osaka catered to men who liked boys. The boys were frequently sold to the brothels when they were children. Some rose to eminence in the “floating world” of commercial pleasure. A print designed by Masanobu in the 1740s shows a male prostitute in a female kimono standing on the tatami floor of a tea house, while a graceful courtesan plays on a samisen and a male client hovers behind a screen. The prostitute’s kimono is decorated with a pattern of lotus roots, perhaps, as the catalog explains, “to suggest the purity of his thoughts rising above the foulness of his profession.”

Perhaps this is true. If so, it is a fine illustration of the way extraordinary refinement can coexist with a basically sordid enterprise. We live in very different times. Boy love still exists, of course, but it is no longer cloaked, even in Japan (pace Inagaki Taruho), with the poetic sentiments of shudo. In most cultures sex with minors is frowned upon. In the West, it is entirely taboo. This is progress. Whether we really need to be shielded from viewing works of erotic art made three centuries ago is, however, open to question.

-

*

The Great Mirror of Male Love, translated by Paul Gordon Schalow (Stanford University Press, 1990), p. 56. ↩