The Bloomsbury painter Vanessa Bell, née Stephen, lived most of her life (1879–1961) in the chilly, concealing shade of her younger sister, Virginia Woolf—the last twenty years following Virginia’s suicide in 1941. Though the attention paid to the Bloomsbury Group seems to be waning on both sides of the Atlantic, there is currently a surge of interest in Bell. Priya Parmar’s novel Vanessa and Her Sister artfully sheds new light on Bell, who is also part of an imaginative group exhibition, “Sussex Modernism: Retreat and Rebellion,” at Two Temple Place in London (William Waldorf Astor’s townhouse, now an exhibition venue). Dulwich Picture Gallery (England’s earliest public art gallery constructed for that purpose) has mounted the first major exhibition of Bell’s work. Her sex life was the chief subject of the BBC series Life in Squares (2015); she was played at different ages by Phoebe Fox and Eve Best.

In 1907, Vanessa married Clive Bell, the art critic and father of her two sons; she briefly became the lover of Roger Fry, the highly admired art critic; and she was the lifelong companion of the gay painter Duncan Grant, whose work will be featured in Tate Britain’s exhibition “Queer British Art, 1861–1967,” opening in April, and who was the father of Bell’s daughter, Angelica. Posterity has judged Virginia the greater artist, but in Parmar’s fictionalized account, Vanessa is the nobler, more sympathetic of the Bloomsbury Group’s founding sisters.

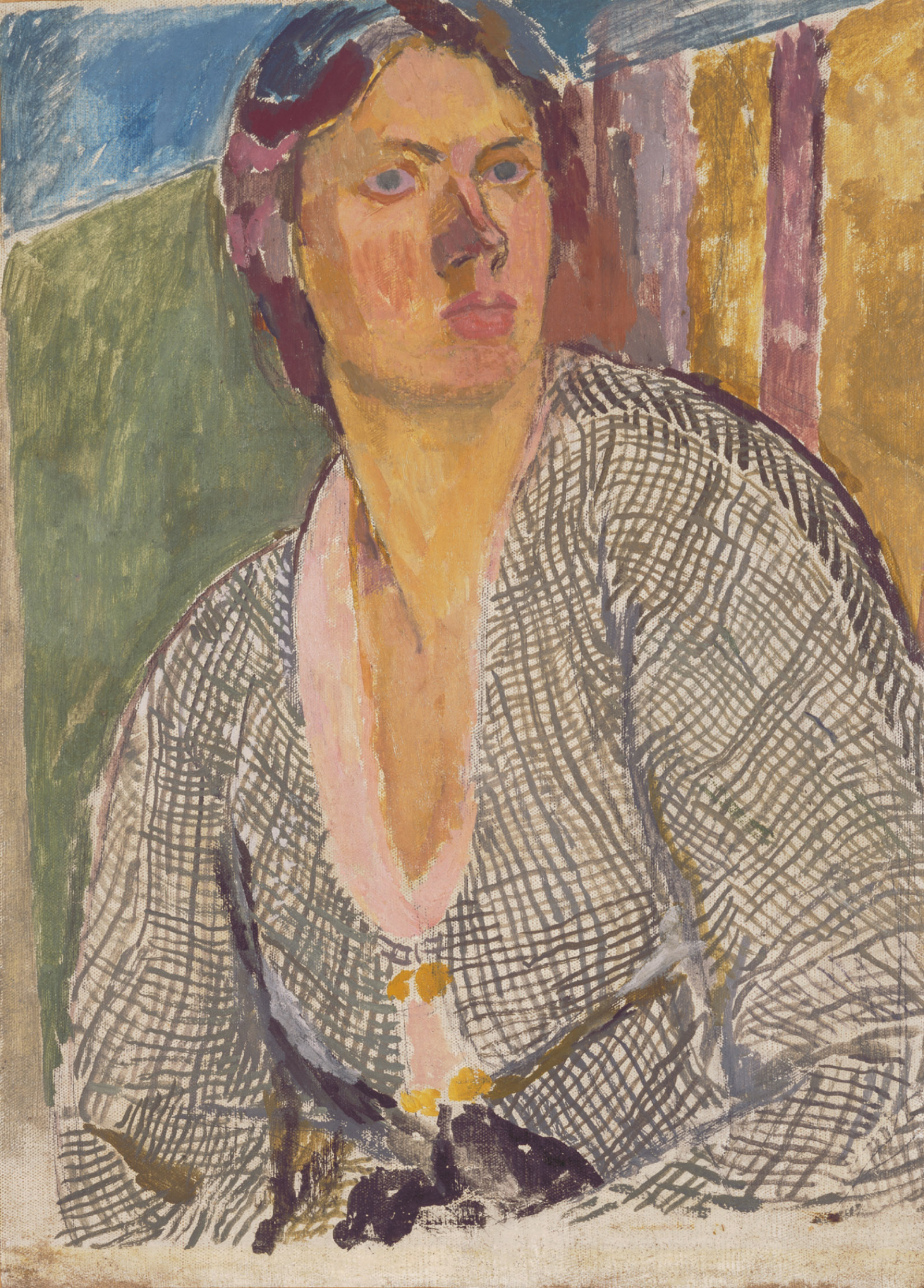

Was Bell a good painter? The striking catalog for the Dulwich show (of seventy-six paintings, works on paper, and fabrics, as well as photographs by both her and Patti Smith) equivocates by stressing her place in art history, saying that she was “one of the most advanced British artists of her time, with her own distinctive vision, boldly interpreting new ideas about art which were brewing in France and beyond.” Nancy Durrant, an art critic for the London Times, agrees: “This show is a joy…. What a magnificent creature she must have been.”

Because Bell spent so much of her life in and expended so much of her art upon Charleston, the Sussex farmhouse (now open to the public) where she lived with Grant, brought up her children, and hosted what the writer Molly MacCarthy dubbed the Bloomsberries, her art is inescapably decorative. Though on the cusp of Abstract Expressionism, for which “decorative” was a reproach, she embraced the domestic application of her artistic skills to crafting Charleston’s curtains, rugs, lampshades, crockery, and even the clothes she wore. At the Royal Academy School, she was taught by John Singer Sargent; there, and at the Slade School of Fine Art, she was influenced by the work of the French Post-Impressionists. Unafraid of the decorative label, Bell featured textiles produced by the Omega Workshop in many of her paintings of interiors, and even portraits. She, Grant, and Fry were the firm’s directors during its six years of existence, from 1913 until 1919.

Bell experimented impressively with pure abstract painting between late 1914 and 1915; before that her landscapes and her occasionally radical, strangely colored, often featureless portraits (such as the faceless pair painted around 1912, Virginia Woolf and Virginia Woolf in a Deckchair) toyed with what she called her sudden liberation, the result of discovering Matisse and Picasso. Although drawn to abstraction, she was adamant that her art needed some element of figuration, saying that “the reason I think that artists paint life and not patterns is that certain qualities of life, what I call movement, mass, weight, have aesthetic value.”

It is left to Vanessa’s grandson, Julian Bell, himself a painter and a first-rate critic, to make her place in art history secure; and also, in his catalog essay, “Landscapes Near and Far,” to champion her artistic worth. “In pictures,” he writes, “there is stuff that you feel you could lay your hands on, and there is stuff that feels forever out of reach.” Cézanne could paint both on the same canvas, and so, he argues convincingly, could Vanessa Bell.

From Parmar’s pages Virginia emerges as an aggressive, often hostile, malicious sibling, and a compulsive flirt. Although based on a huge inquiry into her letters, diaries, and biographies, Parmar’s Virginia is a fictional character who is “raving mad and running all over the house shouting nonsense.”

In a moment of (real-life) folly in February 1909, Lytton Strachey proposed to Virginia Stephen and was—briefly—accepted. Good sense triumphed the next day, and the homosexual Strachey tried to convince Leonard Woolf, then a colonial civil servant in Ceylon, that he ought to marry Virginia, whom he hardly knew.1 Strachey’s marriage-brokering worked, though, as Parmar writes: “They seemed mismatched, like odd socks. Bound together by decision rather than affection.” Parmar gives the reader the same impression about the marriage in 1907 of Clive Bell and Vanessa—that she was not so much in love with Clive as accepting of him and eager to shed her spinsterhood. In fact as in fiction, Virginia began her teasing flirtation with her brother-in-law on a family trip to Cornwall the very next year.

Advertisement

The unconsummated “affair” continued well after the three years that the Bells’ marriage flourished, and even after Virginia’s own marriage in 1912. Clive had taken up with an old flame, and by 1910 Vanessa was interested in Roger Fry. Among Clive’s unpublished letters to Lytton is his comment on November 22, 1913, about Vanessa giving Roger a hard time: “That woman’s a vixen with her lovers you know…I wish Virginia would recover I want to try to have an affair with her”; and, on November 28, 1917: “Virginia, unfucked or almost, alas!, grows more charming with the years.”

In the now vast literature surrounding Virginia Woolf there is speculation about sexual abuse by one or both of her half-brothers, and there are assertions that she was frigid, wrote sexy notes to her husband, and twice had “Sapphic” sex with Vita Sackville-West. With the license allowed the novelist, Parmar has probably hit on Virginia’s genuine secret: she trifled with Clive simply to get closer to her sister. In 1925 Virginia said to her friend Gwen Raverat, “It was my affair with Clive and Nessa…. For some reason that turned more of a knife in me than anything else has ever done.”

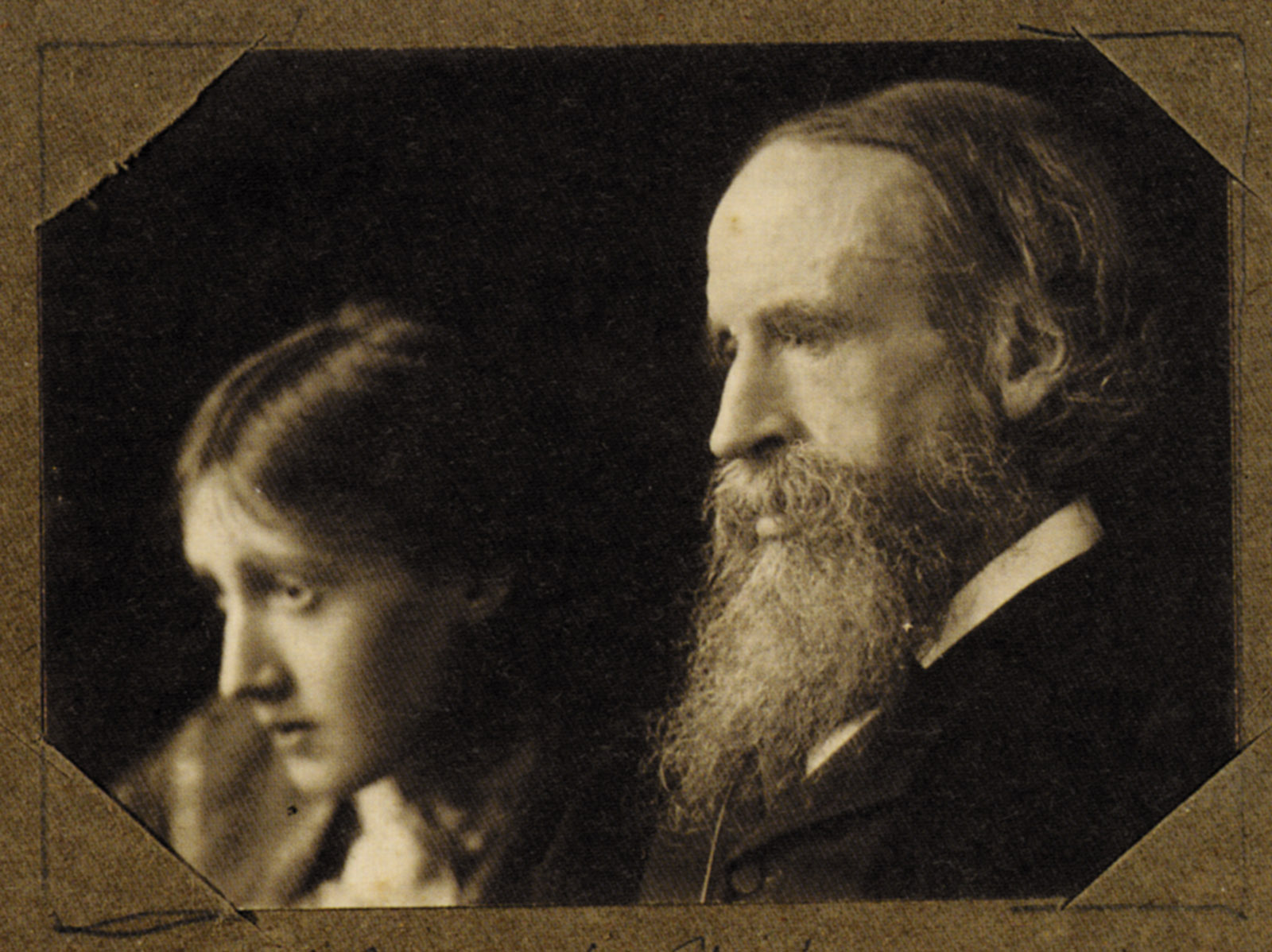

Virginia Woolf’s handsome face, with her high forehead, hooded eyes, prominent cheekbones, and generous nose (inherited from her father, Sir Leslie Stephen, as we can see from the 1902 photograph of them both in profile by George Charles Beresford; see illustration on page 60) is among the most familiar of any writer’s. Dozens of likenesses of her are contained in Frances Spalding’s catalog of the 2014 exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London, “Virginia Woolf: Art, Life and Vision.”

Our easy acquaintance with the face and features of Woolf reflects the consensus of readers and scholars about the range of her genius: a novelist whose most daring experiments, such as The Waves (1931), made their way into the canon; who pretended to stretch the rules to write Flush (1933), the “biography” of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s spaniel, having broken them altogether in Orlando: A Biography (1928), a novel that borrows details from the life of her lover, Vita Sackville-West; yet who also wrote a straightforward biography of Roger Fry (1940).

Few other diarists can be read with such pleasure. Barbara Lounsberry’s Becoming Virginia Woolf: Her Early Diaries and the Diaries She Read shows that the young Virginia was acutely conscious that diaries can be artful and suggests that she was already thinking of what she might draw on for work of her own. Moreover, she was a wise, stylish reviewer of other writers’ efforts; she wrote (and cared) enough about political and social themes to be included, alongside Leonard, on Hitler’s death list in the event of a German conquest of England.

Adeline Virginia was born in 1882, the third of four children of the celebrated man of letters Leslie Stephen and his second wife, Julia Duckworth; she had one half-sister (the probably autistic Laura) by her father’s first marriage to Minny, the daughter of the novelist William Thackeray; and three half-siblings by her mother’s first marriage to the lawyer and country gentleman Herbert Duckworth. Virginia herself alleged that she’d been molested by both Duckworth half-brothers. These assaults have been held to have had some bearing on her recurring mental illness, which had characteristics of bipolar disorder. The family lived in respectable, bourgeois Kensington. Despite the charge of snobbery she consciously courts when she writes in A Room of One’s Own that Shakespeare’s genius “is not born today among the working classes,” she well knew her own social place was not in the upper, but among the middle classes.

Virginia Woolf, notwithstanding her close relationship with her father, felt he had cheated her in not allowing her to have the kind of education she should have had; she bitterly resented having not been sent to Cambridge. She comments emphatically about not belonging at Cambridge in the lectures she delivered there in 1928 and published as A Room of One’s Own (among the most graceful polemics ever published); and she writes frequently in her diary and letters that she begrudged the fact that the family’s money stretched only far enough to educate the two Stephen boys, Thoby (1880–1906, who went to Clifton College when he failed to get a place at Eton) and Adrian (1883–1948, who was at the fee-paying Westminster School). Though Vanessa was sent to a South Kensington art school in 1896 and to the Royal Academy art school in 1901, Virginia was home-schooled, taught mathematics (unsuccessfully) and German (a little more happily) by Leslie, and left to read books from the list he made.

Advertisement

During the two years following her mother’s death in 1895, the teenaged Virginia had no lessons at all, but continued her self-education in the classics, partly in her father’s library. In the autumn of 1897 she was allowed to take Greek and Latin classes at the Ladies Department of King’s College, in Kensington. Two years later she was privately tutored by Walter Pater’s sister, Clara, and then by Janet Case, who became a lifelong friend.

Both Stephen brothers went to Cambridge, attending the grand Trinity College (Leslie had been at Trinity Hall). Many of Thoby’s and Adrian’s friends were members of that most openly secret society, the Cambridge Apostles, although neither of them was invited to join the fraternity, founded in 1820 and boasting Tennyson as its best-known “brother.” Leslie, too, had been overlooked for membership.

With the glaring exception of Clive Bell, almost all of Thoby and Adrian’s Cambridge friends disappeared on Saturday nights in term time, meeting in one another’s rooms to eat “whales” (sardines on toast) and to discuss with conspicuous candor topics such as “the higher sodomy.” The Cambridge Conversazione Society (the Apostles’ formal name) was then under the influence of the philosopher G.E. Moore. Thoby brought his friends home to Kensington, introducing Virginia to the ideas of Moore and to his friends E.M. Forster, Lytton and James Strachey, Saxon Sydney Turner, Leonard Woolf, and John Maynard Keynes.

When Leslie died in 1904, the children moved from the respectable address of 22 Hyde Park Gate, Kensington (with its population, including servants, of up to seventeen other adults) to the five-story house at 46 Gordon Square, in then-louche Bloomsbury. In March 1905 they began holding their “Thursday evenings” there. In her essay “Old Bloomsbury” (written for the Memoir Club around 1922), Virginia writes:

From such discussions Vanessa and I got probably much the same pleasure that undergraduates get when they meet friends of their own for the first time. In the world of [Kensington] we were not asked to use our brains much. Here we used nothing else. And part of the charm of those Thursday evenings was that they were astonishingly abstract. It was not only that Moore’s book [Principia Ethica, published in October 1903] had set us all discussing philosophy, art, religion; it was that the atmosphere…was abstract in the extreme. The young men I have named had no “manners” in the Hyde Park Gate sense. They criticised our arguments as severely as their own. They seemed never to notice how we were dressed or if we were nice looking or not.

The big change to Bloomsbury’s vocabulary and manners came four or five years later, following the terrible blow of Thoby’s death from typhoid in 1906. In her 1924 essay “Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown,” Virginia wrote: “On or about December, 1910, human character changed.” In the Vanessa Bell catalog, Hana Leaper says this sentence referred to “the impact of the first Post-Impressionist exhibition.” Not quite. In the essay, Woolf writes:

At the present moment we are suffering, not from decay, but from having no code of manners which writers and readers accept as a prelude to the more exciting intercourse of friendship. The literary convention of the time is so artificial—you have to talk about the weather and nothing but the weather throughout the entire visit—that, naturally, the feeble are tempted to outrage, and the strong are led to destroy the very foundations and rules of literary society.

Despite the portentous introduction, what really seems to have happened (according to “Old Bloomsbury,” where this anecdote is cited as an illustration of “Bloomsbury Chapter Two,” which ended with the Post-Impressionist show) was this: Vanessa and Virginia were sitting in the drawing room, expecting Clive, and talking.

Suddenly the door opened and the long and sinister figure of Mr Lytton Strachey stood on the threshold. He pointed his finger at a stain on Vanessa’s white dress.

“Semen?” he said.

Can one really say it? I thought and we burst out laughing. With that one word all barriers of reticence and reserve went down. A flood of the sacred fluid seemed to overwhelm us. Sex permeated our conversation. The word bugger was never far from our lips. We discussed copulation with the same excitement and openness that we had discussed the nature of good.

Doris Lessing felt she had Virginia’s measure when she criticized Nicole Kidman’s portrayal of her in the 2002 film The Hours: “Where is the malicious spiteful woman she in fact was? And dirty-mouthed, too, though with an upper-class accent.” Lessing writes this in her foreword to Carlyle’s House (2003), the slightly misleading title given to a small portion of Virginia’s 1909 diary that went missing following Leonard’s death in 1969.

1909 was a remarkable year for Virginia Stephen. In February she and Lytton had their preposterous twenty-four-hour engagement; that summer she refused a proposal from the thirty-year-old journalist and future politician Hilton Young (later the first Baron Kennet). In April her aunt Caroline Stephen left her £2,500, a staggering sum (about $342,600 in today’s money; Vanessa and Adrian got £100 each), and she went to Italy with Vanessa and Clive Bell. In August she went to Bayreuth with Adrian and Saxon Sydney-Turner for the Ring, Parsifal (twice), and Lohengrin. In London there were fancy dress parties, plays, operas, concerts, writing, teaching, German lessons, and excursions to the zoo. Beneath the whirl, the emotionally unstable twenty-seven-year-old was feeling vulnerable and uncomfortable being unmarried, and she despised herself for having such feelings.

In the account in the 1909 diary of having tea in James Strachey’s rooms at Trinity College (along with the man James passionately loved, Rupert Brooke, and their friend Harry Norton), Virginia “admired the atmosphere…and felt in some respects at ease in it.” But only she and Norton spoke, “and I was conscious that not only my remarks but my presence was criticized. They wished for the truth, and doubted whether a woman could speak it.”

Much later, quoting this passage (again in “Old Bloomsbury”), she concluded that the reason for the silence was not antifeminist feeling, but lack of sexual attraction:

The society of buggers has many advantages—if you are a woman. It is simple, it is honest, it makes one feel, as I noted, in some respects at one’s ease. But it has this drawback—with buggers one cannot…show off. Something is always suppressed, held down.

There’s another 1909 sketch written only for her notebooks, baldly labeled “Jews” (in the edited version), which raises the question of anti-Semitism. It’s a portrait of Annie Loeb, a rich and cultivated Jewish woman, whose eminent Wagnerian, stockbroker son Virginia had met three months earlier at Bayreuth. Virginia has two complaints: that Mrs. Loeb’s ambition to marry off her daughters “seemed very elementary, very little disguised, and very unpleasant” and that “at dinner she pressed everyone to eat, and feared, when she saw an empty plate, that the guest was criticising her.” Woolf adds: “Her food, of course, swam in oil and was nasty.” In 1912 Virginia acquired a Jewish mother-in-law of her own, and she often said and wrote unkind and cutting things about her, as she sometimes did about Leonard.

Was this merely conventional anti-Semitism of the early-twentieth-century English drawing room variety? Some have charged that Woolf (and pretty much everyone in Bloomsbury excepting Forster) found Jews on the whole interchangeable and attributed negative characteristics to an entire people. How could Virginia Woolf have been guilty of such lack of imagination? She wasn’t. Before she married Leonard she wrote to several friends with good humor and proud defiance that she was engaged to a “penniless Jew.” One evening in Oxford in the mid-1970s, Isaiah Berlin told my wife and me that when he was young, “I used to meet Virginia Woolf quite a bit. She invariably began the conversation, ‘You know, Isaiah, we Jews…’”

Doris Lessing felt Woolf was not only anti-Semitic, bigoted, and snobbish about “crass middle-class vulgarians” (such as the Wilcoxes in Forster’s Howards End), but also hostile to the lower classes. For Woolf, Lessing writes, “the working people…were enemies.” Even while marshaling evidence for the prosecution, though, Lessing finds a saving grace:

With Woolf we are up against a knot, a tangle, of unlikeable prejudices, some of her time, some personal, and this must lead us to look again at her literary criticism, which was often as fine as anything written before or since, and yet she was capable of thumping prejudice, like the fanatic who can see only his own truth. Delicacy and sensitivity in writing was everything….

Yes, it was everything. But for Woolf these ethereal considerations of art boiled down to hard questions of technique. In her slightest creation, Flush, she manages to incorporate the cocker spaniel’s point of view into the life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning without succumbing to archness. Flush is delicate but substantial, never precious.

Return to her most difficult fiction, The Waves. Start with the italicized narrative conceit of the sea and the sky and the horizon just becoming visible. Read it slowly while thinking about (or listening to) the E-flat major chord that opens Das Rheingold. Bayreuth has worked its effect. Virginia Woolf has captured music: the passage is Wagner’s prelude in prose. Where Woglinde starts her melodic leitmotif, The Waves begins, “‘I see a ring,’ said Bernard, ‘hanging above me. It quivers and hangs in a loop of light.’” Whether it’s homage or imitation, this dialogue can almost be sung to the first lines in the opera.2

Generations of scholars have read The Waves looking for traits that connect the characters with Woolf’s family and Bloomsbury friends, or trying to work out its plot or structure. For the most part, they overlook the connection with the Ring. From childhood Woolf was imbued with Walter Pater’s notion that all art aspires to the condition of music; here she has achieved this goal as fully as the best work in English literature, as well as Joyce did in the final pages of Ulysses. The poetry of The Waves is obvious; it takes only a little effort to hear its music.