It comes as a surprise to a British reader to find World War I routinely referred to, by Americans, as America’s “forgotten war.” The British would never use such a term. It is true that certain significant aspects of the war have faded from the collective memory. Every one of us can remember why World War II was fought (“Hitler had to be stopped”), but few can do the same for World War I. Yes, the archduke had been shot in Sarajevo, but who the archduke was, and why his assassination led to general war, and why the war was or wasn’t worth fighting—that takes a rarer expertise to answer.

The war itself, though, is vividly, viscerally remembered through a series of images, stories, and rituals: bugle music—the Last Post and Reveille, framing the Two-Minutes’ Silence; the wearing of poppies on or around Armistice Day; the trenches; gas masks; the Christmas Truce (a famous moment of unauthorized fraternization on the western front in 1914); shell shock; the refusal to distinguish between the shell-shocked and the malingerer; the brutal idiocy of the generals; women handing out white feathers to noncombatant men; songs and parodies of songs; poets at the front line.

The list expands, contracts, expands again. It holds an abiding fascination for us. But that fascination changes with the decades. When I was a child the standard poppy had a black disk in the center, stamped with the name of the Haig Fund, named for Field Marshal Earl Haig, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force. But over the years the reputation of Haig, the “Butcher of the Somme,” went into such a decline that his name was removed from the poppy. Siegfried Sassoon’s “The General,” written in a hospital in April 1917, gives us a generic World War I commander as he will inevitably be remembered—the affable fool with blood on his hands:

“Good morning; good morning!” the General said

When we met him last week on our way to the line.

Now the soldiers he smiled at are most of ’em dead,

And we’re cursing his staff for incompetent swine.

“He’s a cheery old card,” grunted Harry to Jack

As they slogged up to Arras with rifle and pack.

But he did for them both by his plan of attack.

Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, officers highly critical of the war and yet prepared to return from the hospital to the front (Owen to be killed a week before the Armistice), are the outstanding war poets. And war poets in this sense were something new: brave combatants in a campaign they detested, they speak to us with an unanswerable authority.

But it was an authority not to be replicated in other countries or other conflicts. Just as the British tradition offers no equivalent to Walt Whitman’s poetry of the Civil War, so the American tradition seems to lack its Owen. Searching through A. Scott Berg’s excellent anthology, World War I and America, one comes up with very little poetry at all—Robert Frost’s “Not to Keep,” a passage from Ezra Pound’s “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley”—until, near the end, with a grin of recognition, one turns to E.E. Cummings’s sardonic and, for 1926, audacious “my sweet old etcetera.” A trench poem indeed, whose author had served in the ambulance corps. But Cummings seems a very long way from Owen.

David Reynolds, in the catalog to “World War I and American Art,” points out that among all the monuments on the National Mall in Washington, there is no national memorial to the soldiers who died in World War I. There is a small temple dedicated to the citizens of the District of Columbia who served in that war, giving the names of the 499 who died. There is the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri, but there is nothing in Washington to commemorate the 116,516 lives lost in all, of whom slightly more than half fell victim to influenza and pneumonia.

America was involved in serious combat, Reynolds points out, for less than six months. The US commander, General John J. Pershing, a man apparently cut from the same cloth as Sassoon’s unnamed general, “lost 26,000 men in little over a month—carnage far worse than the Civil War battles of Shiloh, Antietam, Gettysburg, and Cold Harbor put together.” The total number of American soldiers killed in those six months is roughly the same as those killed over twenty years in Vietnam.

No monument, no great body of poetry? Is there perhaps a prose writer who speaks for a generation? Here perhaps the best answer is Ernest Hemingway, who appears in Berg’s anthology as the author of the admirable short story “Soldier’s Home,” a study of what would come to be known as post-traumatic stress disorder. Hemingway’s experiences were on the Italian front, and led to the composition in 1929 of A Farewell to Arms. There are other well-known names Berg has assembled. Edith Wharton turns out to have been a vivid reporter from just behind the front line. Frederick Pottle, best known much later as the distinguished editor of James Boswell, appears here as a surgical assistant, treating casualties from the Battle of Belleau Wood in 1918.

Advertisement

But then, and in greater number, there are names of onetime star reporters or simple private witnesses, forgotten now, here retrieved and notable for the bravura of their style. If this comes from the magazine culture of the period, rather than from any single individual, one can only applaud that culture. It affects a devil-may-care gallantry at times, but it is well equipped, when the moment comes, to answer the questions we want to pose. Here is Floyd Gibbons, introducing an account of “How It Feels to Be Shot”:

Just how does it feel to be shot on the field of battle? Just what is the exact sensation when a bullet burns its way through your flesh and crashes through your bones?

I had always wanted to know. As a police reporter I “covered” scores of shooting cases, but I could never learn from the victims what the precise feeling was as the piece of lead struck. For long years I had cherished an inordinate curiosity to know that sensation, if possible, without experiencing it. I was curious and eager for enlightenment just as I am still anxious to know how it is that some people willingly drink buttermilk when it isn’t compulsory.

The absurdity of this comparison is part of the self-deflationary tactic of the lead-in. Without any hint of heroics, he is going to tell us precisely what it was like to get shot in the eye in Belleau Wood.

A light style and a careful use of understatement make for an attractive read. But the fact is that sometimes they limit the impact an author can make. Something similar happens with a painter like John Singer Sargent, whose watercolor style always pleases, where perhaps pleasure is not the emotion we would want. Sargent, cast against type as a war artist for Lord Beaverbrook’s British Ministry of Information, found some difficulty in choosing a subject to illustrate the theme he had been given: “British and American Troops Working Together.” He complained: “They do this in the abstract but not in any particular space within the limits of a picture.” He experienced a problem with which anyone who has tried to take a photo at a front line may sympathize: there’s nothing to see. “I have wasted lots of time going to the front trenches,” he wrote to a society hostess. “There is nothing to paint there—it is ugly, and meagre & cramped, & one only sees one or two men.”

Finally, traveling with the painter Henry Tonks, Sargent found a group of soldiers who had been blinded by mustard gas, making their way toward a dressing station. At once he dropped his theme and made the line of blind soldiers his subject. The resulting oil painting, Gassed, is the most ambitious loan and the chief object of artistic interest in the exhibition. It owes its strength to Sargent’s skill as a muralist and to the quiet directness with which the subject is presented.

If you compare Gassed with the German depictions of war victims (by artists like George Grosz and Otto Dix), then its relative understatedness might seem to verge on the timid. But Sargent was never going to paint like Dix. If one considers it as an official government commission, then it is difficult to think of a precedent for its plain presentation of the human price of modern war. Sargent had been asked for an inherently upbeat subject (cooperation between allies). Instead he chose this Owenesque theme (mass mutilation).

Nobody seems to have complained. Nobody was in a position to complain. But when the painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1919, something about it disgusted Virginia Woolf. One of the blind men in Gassed seems to have been warned that there’s a step ahead of him, and he raises his leg far higher than he needs in order to negotiate the obstacle he cannot see. This touch (perhaps, after all, something Sargent had seen for himself), this “little piece of over-emphasis,” struck Woolf as intolerable. Coming after a long series of manipulative touches in the Academy’s Summer Exhibition,

Mr Sargent was the last straw. Suddenly the great rooms rang like a parrot-house with the intolerable vociferations of gaudy and brainless birds. How they shrieked and gibbered! How they danced and sidled! Honour, patriotism, chastity, wealth, success, importance, position, patronage, power—their cries rang and echoed from all quarters.

And with that Woolf ran down the great Academy staircase and out into Piccadilly.

Advertisement

“World War I and American Art” brings together work of uneven quality, some of it more for its documentary than its artistic interest. For instance, I do not think that George Bellows is well represented as an artist by the horrible set of images he thought up (graphite drawings, lithographs, and paintings) after reading accounts of German atrocities in Belgium. But they certainly have a place in the history of war propaganda, Bellows having switched from pacifism to extreme bellicosity.

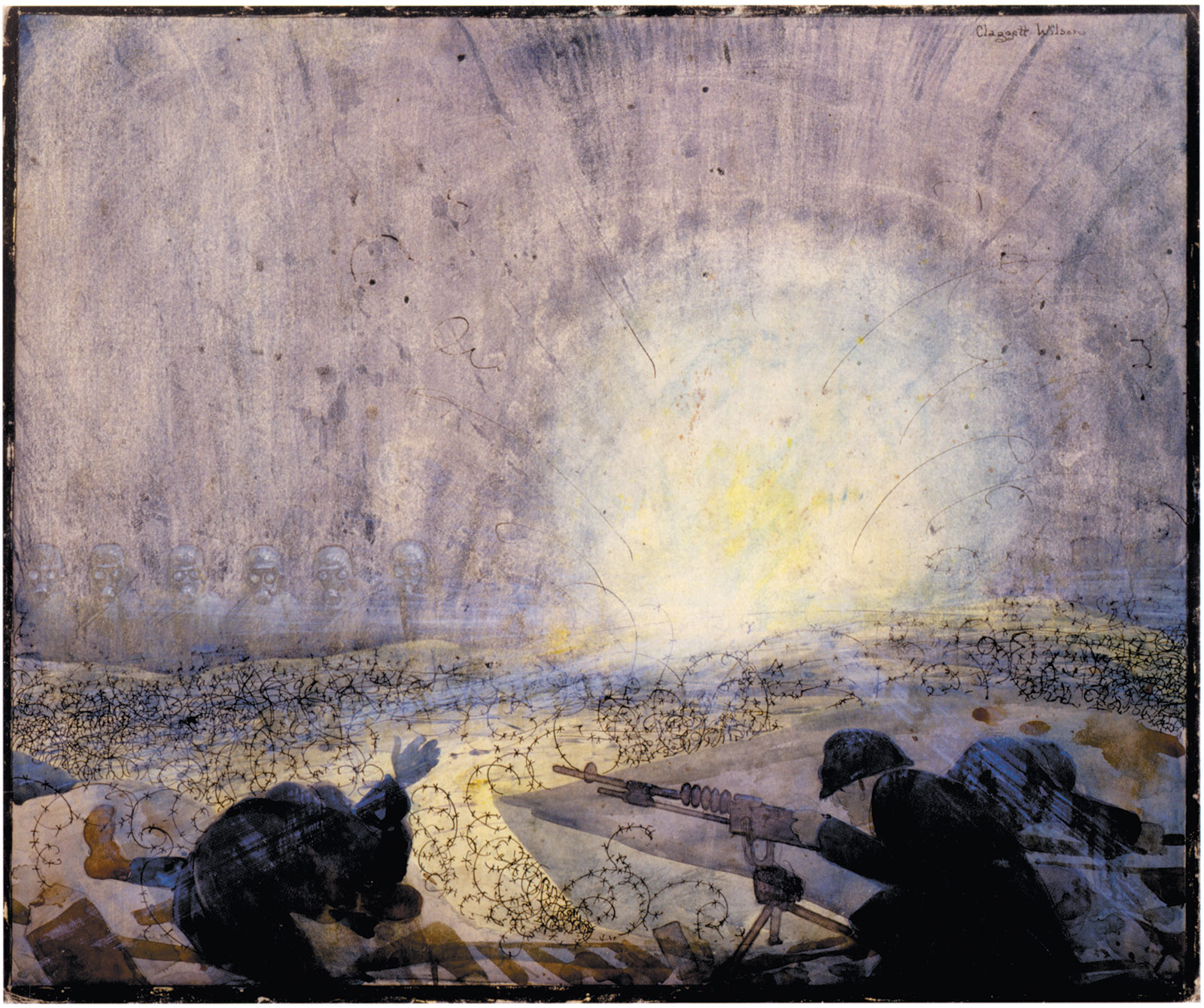

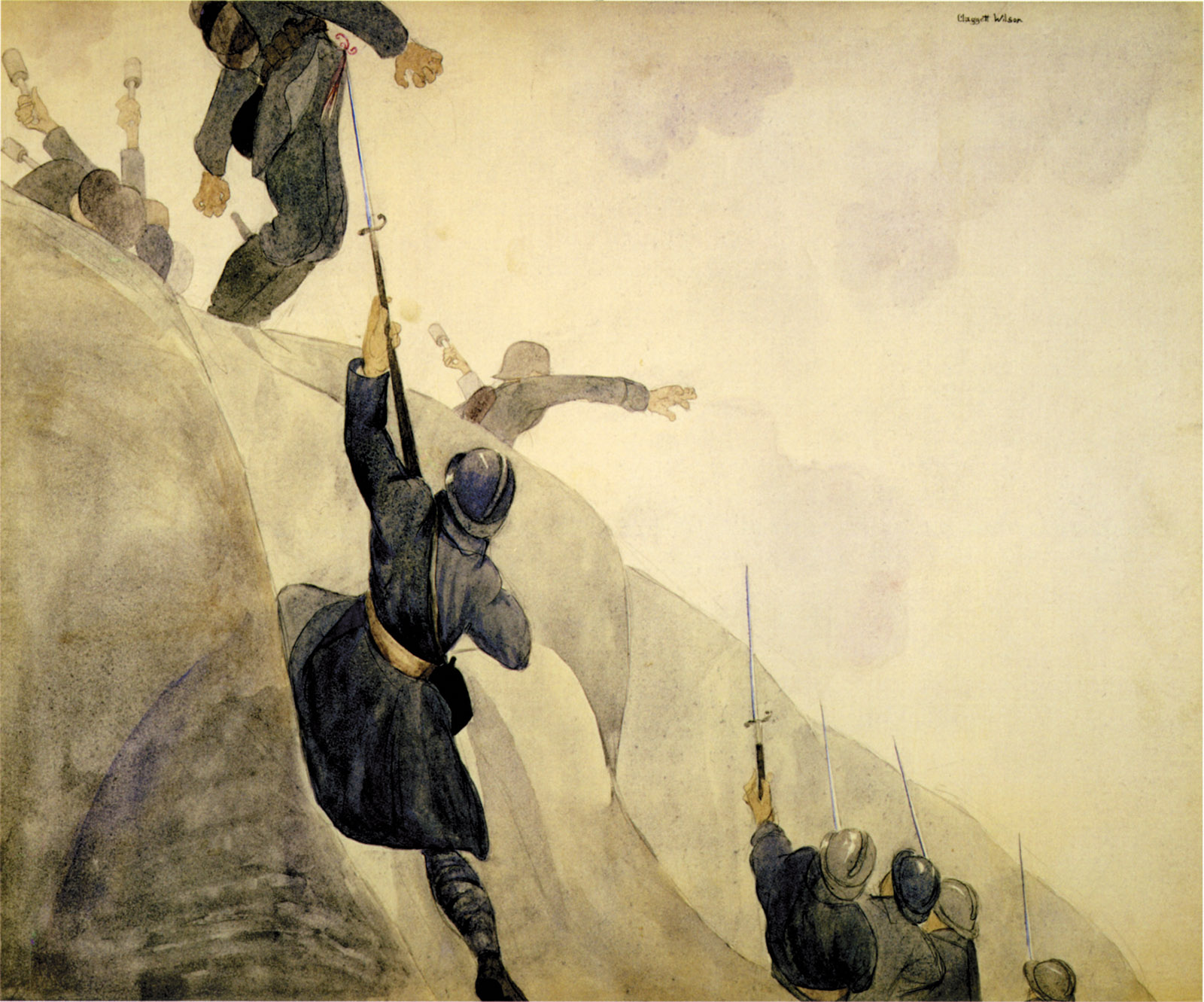

A quite extraordinary set of images by an otherwise unknown artist, Claggett Wilson, made with watercolor and pencil on paperboard after the war, brings back images from the thick of the fighting in Belleau Wood, and represents an attempt to convey what it was that drove men out of their minds. If the way back to sanity, in the postwar years, meant facing up to your demons, then these strange cartoon-like images, with their long, specific titles (“Runner Through the Barrage, Bois de Belleau, Château-Thierry Sector; His Arm Shot Away, His Mind Gone”), hold a place in the history of therapy as well as that of combat. “Rosalie, Rosalie! Rosalie Is the Nickname for the French Bayonet” is horribly informative about hand-to-hand fighting.

There are great curiosities. Winsor McCay, the wonderful illustrator, made an eleven-minute animated film of The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918). Edward Steichen worked in aerial photography, and there is interesting material on camouflage, both the familiar kind and the extraordinary “dazzle” camouflage, which was designed to confuse the eye as to the shape and outline of a ship. Where the familiar kind was about blurring outlines and contours, the dazzle effect worked by painting a sharp high-contrast design that flatly contradicted the physical outlines of the vessel, in a way that reminds one of Cubism and, much later, Op art.

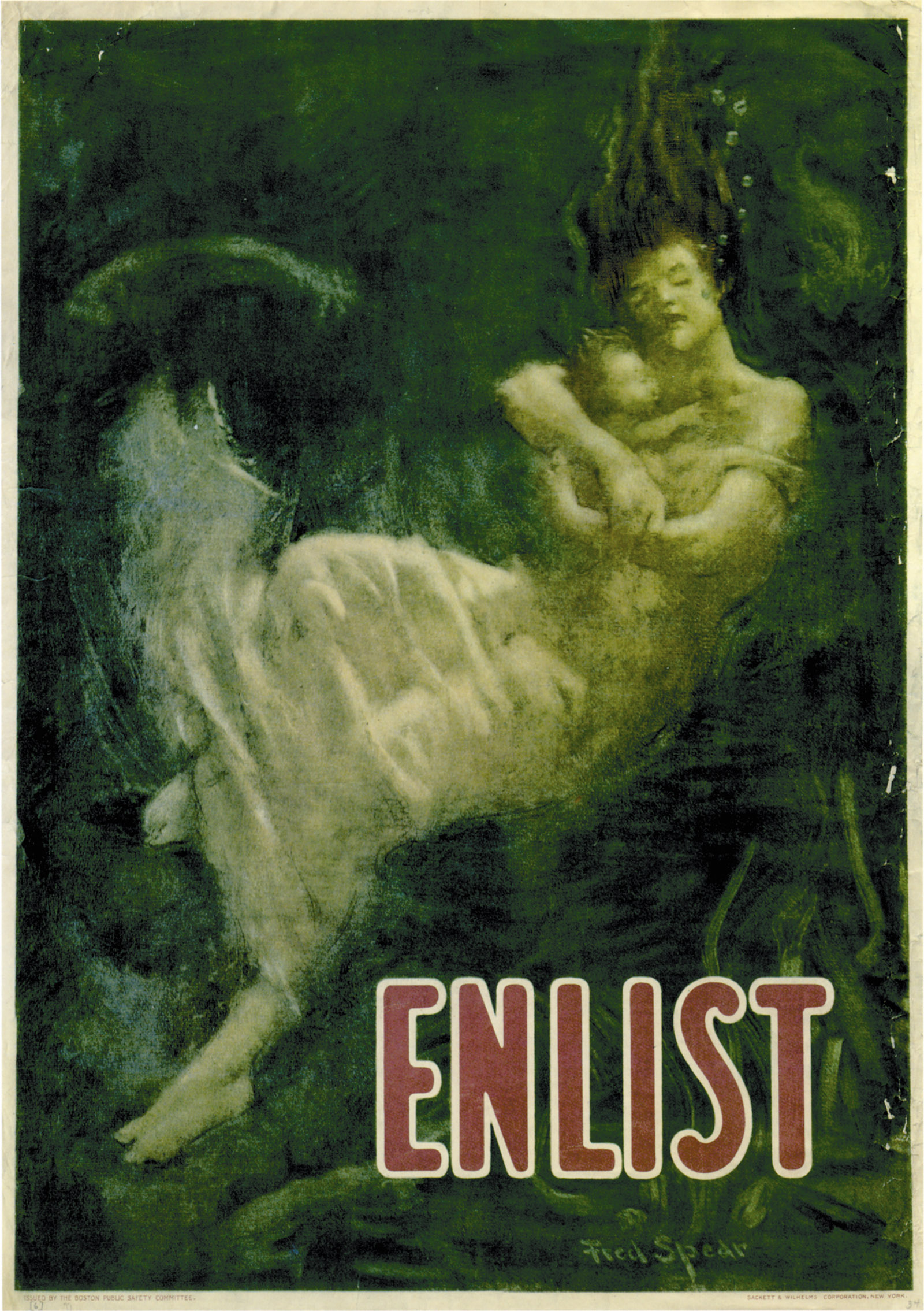

Both the Philadelphia exhibition and the recent one at Vassar, “The Art of Devastation,” showed numerous posters from the period, none more striking than Fred Spear’s image of a woman underwater, drowning with her baby in her arms. The text on the poster is one word: Enlist. The unspoken reference is to the sinking of the Lusitania, an event that made it hard for America to stay out of the war. You must fight, says the poster, because motherhood is under attack. And another poster says: you must buy bonds in the Fourth Liberty Loan, because the Germans are raping women. “Destroy This Mad Brute, Enlist,” says a third, showing a Prussian ape with a cudgel marked “Kultur” and a bare-breasted woman swooning in his grasp.

It is striking how often in this period the war is presented as an issue of manhood, of womanly values, motherhood, virginity at stake, plain old sex. The woman’s point of view was instantly co-opted. Here is the chorus from Alfred Bryan’s hit song “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier”:

I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier,

I brought him up to be my pride and joy,

Who dares to place a musket on his shoulder,

To shoot some other mother’s darling boy?

Let nations arbitrate their future troubles,

It’s time to lay the sword and gun away,

There’d be no war today,

If mothers all would say,

“I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier.”

That was the winning point of view in 1915, when 650,000 copies of the sheet music for the song were sold in three months. But it was immediately answered by parodies, along the lines of “I did not raise my boy to be a coward,” or a “Molly-Coddle.” The opposite perspective had been successful in Britain in 1914, as expressed in the words of Arthur Wimperis and Herman Finck. The vaudeville singer offers sexual initiation to the young recruit:

On Sunday I walk out with a Soldier

Monday I’m taken by a Tar

Tuesday I’m out with a baby Boy Scout

On Wednesday a Hussar

On Thursday I gang out wi’ a Scottie

On Friday the Captain of the crew

But on Saturday I’m willing if you’ll only take the shilling

To make a man of any one of you.

This sexualization of the war was surely something new. In German propaganda it reached its ultimate expression in a medal designed by Karl Goetz and protesting the French occupation of the Ruhr, in which the usual allegorical victim-woman is tied to a giant erect phallus.

The word “medal” in this sense refers not to military decorations or medals given as awards in competitions, but to commemorative medals—coin-like disks with no fixed monetary value, cast or struck usually in metal, to commemorate or comment upon recent events. The tradition goes back to the Renaissance, when the master medallist was Pisanello. At various times subsequently people introduced a satirical or overtly propagandistic element to the medal, and during World War I this tradition was particularly strong in Germany.

It was an idiom that the American sculptor Paul Manship found to lie perfectly within his grasp, and his medal, “The Foe of Free Peoples,” looks at first glance very like a German medal. But it is anti-German. On the obverse, Kaiser Wilhelm II is depicted with a helmet, wreath, and rosary of skulls, together with a bayonet. On the reverse, the text reads “Kultur in Belgium, Murder Pillage.” The Kaiser is seen running off with a woman in his arms, while a child lies on the ground beneath, presumably dead.

Medals of this kind might be used for charitable purposes, as in the case of Manship’s “The French Heroes Fund,” in which the running figures (that make such a lively composition on a medal) are the French heroes, bayonets fixed, running off into the cloud of war and leaving the prone figure of a German soldier surrounded by sprouting fleurs-de-lys. On the reverse, Marianne is depicted protecting children, with the text: “America aids the children of France.”

The medals in the Vassar show come from the American Numismatic Society’s collection. They represent an art that was at its liveliest in the early part of the last century. It begins in the Art Nouveau or Jugendstil idiom. It continues as a miniature department of Expressionism and, in Manship’s case, Art Deco. It is intimately connected with cartoons and, as demonstrated by the show, the graphic art of posters. But it is a form of sculpture, offering the medallist the challenge of packing meaning onto one or both sides of a disk. It is not always, as we have seen, respectable. In fact it expresses furious resentment and prejudice.

A French medal by André Pierre Schwab shows a skull of a German soldier in his spiked helmet, with the inscription Il n’est de bon boche que boche mort: the only good Hun is a dead Hun. And the Karl Goetz medal mentioned earlier, in which the woman is tied to a giant phallus, protests specifically against the French use of black troops on the Ruhr, and has a racist depiction of a black soldier on the obverse. (It was not shown at Vassar, falling outside the time frame of the show.)

The German medals celebrate what other nations deplore—the actions of the U-boats, the sinking of the Lusitania. Ludwig Gies made an oval cast-iron medal called “The Torpedoed,” which simply shows a crowded lifeboat and more people swimming alongside. His medal on the sinking of the Lusitania shows the enormous bow of the ship, ready to go down, while passengers are lowered in lifeboats or wait on deck. There is absolutely no sense here of regret at “collateral damage” in war. Quite the opposite.

Goetz’s famous depiction of the same event shows on the obverse the Lusitania going down, beneath the inscription “No contraband.” But the deck of the ship is loaded with aircraft and cannon. Along the base of the image (the field called the exergue) the text reads: “The steamer Lusitania sunk by a German submarine.” The reverse of the medal is extraordinary. It shows the Cunard ticket booth in New York, with Death selling tickets from the kiosk. Near the line, a man stands reading a newspaper with the headline “U-boat danger.” A top-hatted figure, the German ambassador to the US, Count Johann-Heinrich von Bernstorff, raises a finger in warning, but the inscription above his head reads: “Business above all else.” They were warned, says the medal, and they were carrying arms. They deserved what they got.

This Issue

May 25, 2017

In the Horrorscape of Aleppo

Calculating Women