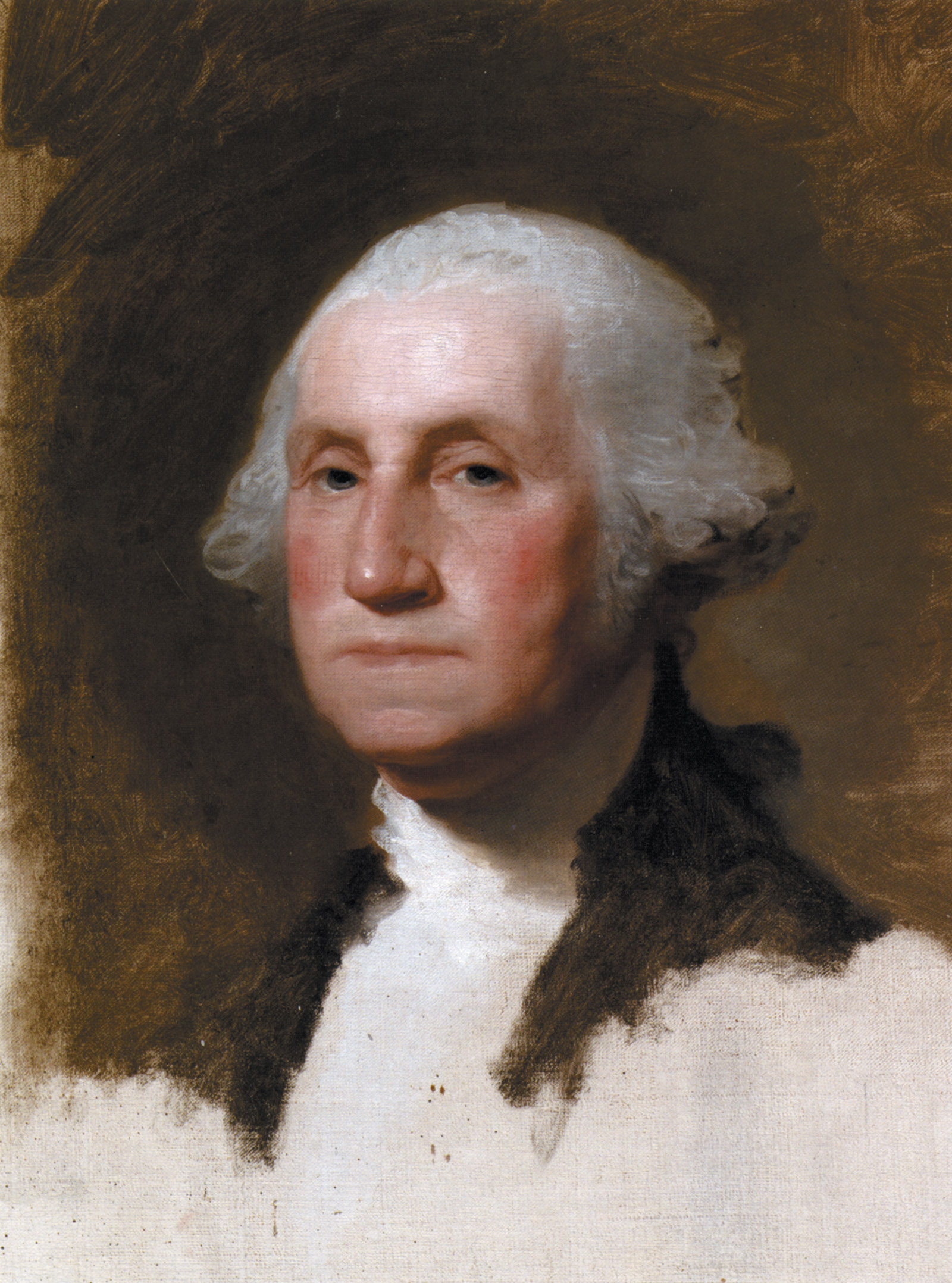

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian, Washington, D.C./Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Gilbert Stuart: George Washington (The Athenaeum Portrait), 1796; from Susan Rather’s The American School: Artists and Status in the Late Colonial and Early National Era, published by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press

In 1968 Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act to take effect in 1971. It moved the observance of several holidays to Mondays in order to create more three-day weekends for the nation’s workers. In the case of George Washington’s birthday, which had traditionally been celebrated on February 22, Congress designated the third Monday in February as the new holiday. Because February is the birth month of Abraham Lincoln and several other presidents, including Ronald Reagan, that day soon came to be popularly known as Presidents’ Day.

Although the federal government still refers to the Monday holiday as Washington’s Birthday, the Uniform Monday Holiday Act has had the effect of turning our first president into just another one of the forty-four that followed him—a terrible mistake that diminishes the unique greatness of Washington. It’s a mistake because Washington had challenges and responsibilities that no other president, including Lincoln, has ever faced. Lincoln saved the Union, but Washington created it. Without Washington there might never have been a United States for Lincoln to save.

Or so T.H. Breen persuasively argues in his neat and readable account of Washington’s efforts as president to forge a new nation. The president aimed to do this personally by traveling through all the states and engaging in conversations with his fellow citizens. Although Breen has entitled his book George Washington’s Journey, the president actually made several separate journeys: one, his trip from Mount Vernon to New York in the spring of 1789 to be inaugurated as president; a second in the fall of 1789 to New England, bypassing Rhode Island, which had not yet ratified the Constitution; then in August 1790 a short jaunt to Rhode Island after it had joined the Union; and finally between March and July 1791 an extended journey of eighteen hundred miles through the southern states.

Washington is the only president in American history who had to be virtually dragged into accepting the office. As the successful commander-in-chief of the Continental Army that had beaten the British and guaranteed American independence, Washington in the mid-1780s was an international celebrity. Having already achieved fame—the love of which Alexander Hamilton said was “the ruling passion of the noblest minds”—he was reluctant to risk it. After eight years of fighting he yearned to remain in private life and enjoy what he referred to as its “domestic felicity.” But he knew he had to accept the presidency. The Constitutional Convention of 1787 had made the executive office so independent and so powerful precisely because the delegates believed that Washington would hold the office, and they trusted only him. Some thought of the president as an elective monarch who would serve in the office for life, something not out of the question in the eighteenth century. With great reluctance Washington set off from Mount Vernon in April 1789 for the temporary capital of New York, feeling, as he told his friend Henry Knox, like “a culprit who is going to the place of his execution.”

Breen suggests that the idea of a journey throughout the country probably came to Washington during this trip to New York in the spring of 1789. Everywhere he was saluted by cannons, songs, triumphal arches, and illuminations, and greeted by huge enthusiastic crowds acclaiming “Long live George Washington.” Although Breen emphasizes that the outpourings of popular enthusiasm for Washington were simply “ordinary Americans—pushy, loud, excited, joyful, and demanding”—expressing “a new open, participatory political culture,” they were also reminders that most adult Americans had not long before been subjects of a king and that some of them were still emotionally involved in aspects of monarchy. Indeed, historians are only now coming to realize just how widespread monarchical thinking was in the 1780s, especially in New England. Consequently, Washington’s journey took on the air of a royal procession, sometimes not all that different from the royal entries and monarchical progresses common to medieval and early modern Europe.

Washington was deeply embarrassed and alarmed by all the monarchical sentiments and ceremony he encountered. With friends telling him that he was “now a King, under a different name,” and imploring him “to reign long and happy over us,” he went out of his way to emphasize the republican character of both himself and the new federal government. In an early draft of his inaugural address he even stressed that he had no heirs, “no family to build in greatness upon my country’s ruins,” until James Madison persuaded him to cut out these monarchical references. Washington’s eagerness to deny all kingly ambitions, however, reveals just how prevalent was the talk of monarchy in 1789.

Advertisement

As Breen points out, Washington came to realize that he had to learn how to counter these monarchical sentiments and present himself to the newly enlarged public as a strictly republican leader. Although it was important to him to maintain “the dignity & respect which was due to the first Magistrate,” he did not want the office to become “an ostentatious imitation, or mimicry of Royalty.” He was not at all happy when his vice-president, John Adams, created a storm of controversy by persuading the Senate to endorse as a title for the president “HIS HIGHNESS THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, AND PROTECTOR OF THEIR LIBERTIES.” To Washington’s great relief the House of Representatives, under James Madison’s leadership, killed the Senate’s proposal and substituted the simple title of Mr. President.

Washington had no desire whatever to become a monarch-like leader—“a kind of American Oliver Cromwell”—which, as Breen correctly suggests, he could easily have become, “translating immense personal popularity into permanent national office.” The fact that everyone knew that he would never go down that path—in fact, knew that he only yearned to be back in Mount Vernon—was the source of his extraordinary political influence. As Garry Wills once nicely put it, Washington “gained his power by his readiness to give it up.”

Since Article II of the Constitution is very brief and vague on the duties of the president, Washington faced the awesome task of fashioning the character and responsibilities of the office. In effect, he created the presidency and in the process, as Breen says, invented “a republican theater of politics” for the new nation. Washington loved the theater and often attended it for entertainment and relaxation. He commonly saw himself as an actor on stage and was always concerned with maintaining appearances. As John Adams later lamented, Washington had all the political talents that he, Adams, lacked. Washington had the gift of silence and had mastered “the theatrical exhibitions of politics.” He may not have been the greatest president, said Adams, but certainly “he was the best actor of presidency we have ever had.”

Washington used theatrical imagery everywhere in his writings. He described the creation of the Constitution, for example, as a great “Drama,” greater “than has heretofore been brought on the American Stage, or any other in the World.” As president he was obsessed by what he should wear, how he should meet the public, what kind of coach he should appear in. He was keenly aware that as the first chief executive he was entering “untrodden ground” and that he was setting precedents for future presidents. These precedents, he told James Madison, therefore had to be “fixed on true principles.” Since the United States was the largest republic since the fall of Rome, the government’s fate might actually determine the future of popular government for all time. “The eyes of America—perhaps of the world—,” said Washington, “are turned to this Government; and many are watching the movements of all those who are concerned with its Administration.”

What Washington worried about most was preserving the fragile Union that had come out of the Revolution. Winning independence in 1783 was crucial, but it did not guarantee the success of the republican experiment. Without a strong central government to curb the self-interest of the separate states, the nation could easily fall apart. Fear of disorder and anarchy had led to his willingness in 1787 to come out of retirement and attend the convention in Philadelphia that had drafted the Constitution.

In ratifying that Constitution the people in the several states had radically changed the political culture of the nation. Most white adult males had participated in politics in ways they never had before. “Ratification,” says Breen, “opened the door to public opinion, to politics out of doors, and to conversations with ordinary Americans about the future of government.”

Washington realized that most Americans in 1789 were still emotionally attached to their states. When most people talked about their “country,” they usually meant their states, which as colonies had earned the loyalty of their inhabitants during a century or more of history. By contrast, the people’s recent connection to the abstraction of the United States was bound to seem tenuous. Weaning the people from their attachment to their states and tying them to the new federal government would not be easy. Everywhere there were narrow-minded opponents of the new government—“disappointed expectants and malignant designing characters,” Washington called them. These “political Mountebanks” were trying to undermine the new Constitution without giving it a chance. At the same time, Washington complained, increasing numbers of newspapers were spreading “scurrility & malignant declamation” and poisoning public opinion with falsehoods.

Advertisement

The president’s task was thus formidable. Somehow he had to get around the self-appointed gatekeepers of public opinion and reach the people directly in order to create new bonds of loyalty to the Union. The best way to do that was to take the federal government to the people in person and communicate with them directly, away from the partisan press and the factious parochial politicians. This was the reasoning behind his decision to undertake his presidential journeys throughout the country.

Vice-President Adams turned down Washington’s invitation to accompany him on his journey to New England. Adams thought the president was making a big mistake to go traveling around the country when so much had to be done at the capital. But Washington was so determined to bring the government to the localities of the nation that Adams began to have second thoughts. Perhaps the vice-president didn’t understand the popular character of the new nation as well as the president. “My long Residence abroad,” Adams conceded, “may have impressed me with a View of Things, incompatible with the present Temper or Feelings of our Fellow Citizens.”

In order to ensure that his travels would not resemble the royal progresses of European monarchs, Washington asked the several localities he intended to visit not to hold any parades or special ceremonies in his honor. Of course, the cities and towns entirely ignored his wishes. The people were desperate to see and honor the president with festivals, receptions, and parades. But Washington did his best to make the progress a republican one. Approaching a town, he left his coach and rode into the community on horseback, at first in a civilian suit, but later in his military uniform as commander-in-chief. He refused to burden any private citizen with the expense of putting him up, along with his entourage, and instead stayed and dined only at public inns and taverns, which in many cases, as Breen points out, “provided dubious food and uncomfortable beds.” In fact, Washington turned his diary into a kind of travel guide, describing in detail just where the best and worst places to stay and dine were. Unfortunately most places were, in Washington’s words, “extremely indifferent.” The problem with the public inns, he concluded, was that they catered to the public, not to the likes of him.

To town after town Washington brought a message of the advantages and benefits of the new national government. Acutely aware of precedence, he outmaneuvered Governor John Hancock of Massachusetts, who had sought to assert the superiority of his state over the federal government. In his short visit to Rhode Island, whose earlier refusal to join the Union he had railed against, he visited the Touro Synagogue in Newport, where the Jewish congregation greeted him warmly, thanking him for leading “a Government, which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance.”

Washington’s response, in a letter written a few days after he left Newport, became one of the great documents in American history. The president told the Jewish congregation of the Touro Synagogue that America had established “an enlarged and liberal policy: a policy worthy of imitation. All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship.” In place of mere toleration, which was just an indulgence, the United States, said Washington, had created true religious liberty, where “every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and figtree, and there shall be none to make him afraid.” An exaggeration, no doubt, since the First Amendment had not yet been ratified and several states still maintained religious establishments, but a worthy expression of Washington’s enlightened hopes for the future.

With the need to reinforce feelings of Union very much on his mind, Washington reminded his fellow citizens of what it meant to have gone through the Revolutionary War together. He seized control of the country’s recent history and used the common memories of the Glorious Cause to counter the emotional attraction of local identities. “In communities throughout the nation,” writes Breen, “ordinary people watched as their president visited the places where Americans had fought and died for independence, sites of national sacrifice.”

Through newspaper accounts people up and down the continent watched Washington reexperiencing the Revolution. Veterans of the war everywhere came out to pay their respects to their former commander-in-chief. When he stopped at Lexington in 1789 he noted in his diary that he had been at the place where the “first blood was spilt.” American blood, says Breen, not just Massachusetts blood.

Breen emphasizes the radical character of the Revolution. It achieved, he says, far more than national independence; it overturned the traditions of an aristocratic world and created a new egalitarian republican culture. Ordinary white men now “imagined themselves to be social equals,” and as such they sought to play their own separate roles in integrating the president into their lives. “No longer subjects of the Crown, they prided themselves on being republican citizens.”

Although the colonists had often held processions honoring their royal governors, no one had ever experienced anything like the huge and raucous public spectacles designed to honor Washington. People organized parades that contained elaborate floats and marching militia companies; they built huge triumphal arches and in Boston even erected a “Colossal statue” of Washington under which people could walk; they fired cannons and displayed special flags in honor of the president; they gave fulsome speeches and held elaborate dinners and at night often illuminated their entire city. The practice of general illumination became so common that those who failed to light their windows with candles feared they would suffer discrimination or even violence.

The tradition of toasting, which in the eighteenth century carried particular cultural weight, became an important ritual by which public conversations took place. Washington usually began with a toast to the local community, which was followed by a dozen or more toasts by the local organizers. These toasts became, writes Breen, “an important vehicle for political communication, linking local groups to the head of the new federal government.” Because simply having the president in their town or city seemed liberal and cosmopolitan, the local authorities were inclined to pass over their provincial interests and respond to him by expressing the national and sometimes international concerns that he expected. Their toasts tended to affirm a vision of the Union and the role of America in the world that Washington heartily endorsed.

These ceremonies were bottom-up affairs, and Washington could scarcely control what was happening. Ordinary people felt they had as much right to participate in them as elites. As someone who always felt at ease with women, Washington especially welcomed the presence of scores of them at the various occasions. He believed the attendance of so many women at the parades and ceremonies, the numbers of which he dutifully recorded in his diary, was a sign of how far America’s civilization had advanced. Even when they never actually spoke with the president, women conveyed their support of him through emblems and devices. In New Hampshire, reported one newspaper, “the Ladies have invented sashes, on which the bald Eagle of the Union, and G.W. hold conspicuous places.”

Taking part in bottom-up affairs, people often made demands of Washington that he patiently tried to accommodate. They requested his portrait, and as much as he hated sitting for portraits, he usually complied, sitting for dozens of them during the course of his career, not out of egoism but out of the realization that he had come to stand for the Union and that his portrait helped to bond people together. Turning out in great numbers at the many parades and festivals, “ordinary men and women,” writes Breen, “suddenly found themselves caught up in a transcendent event that for many of them became a defining moment in their lives.” It is not surprising therefore that many people became speechless when they actually confronted the great man.

As much as Washington sought to minimize all aspects of monarchy in his tours, people often responded as if he were their king, sometimes addressing him as “His Majesty the President.” In town after town crowds belted out the song that Englishmen had greeted George II with sixty years earlier: “He Comes! He Comes! The Hero Comes. Sound, sound your trumpets. Beat your drums.” Some people even treated him as if he were a god. He was addressed with a variety of titles: “beloved Father of the great American Family,” “the political father and savior of his country,” “Great Deliverer of our Country,” “Columbia’s favorite son,” the “Delight of Human Kind,” and “His Most Patriotic Majesty.”

Of course, there were critics of these elaborate titles and distinctions. Such honors existed, said one Massachusetts writer, only in countries where “the mass of the people” lived in an “enslaved condition.” “The more free the constitution of any country, the less we see of pageant, titles and ceremonies.” Since these things merely demonstrated “the inferiority of various classes of men in the presence of their superiors in rank,” they had no place in an egalitarian republic. Despite this sort of criticism, however, there is no doubt that Washington was regarded with a kind of awe and reverence granted to no other figure in American history.

Washington’s extensive southern tour in the spring of 1791 took place under very different political conditions from those of the earlier journeys. Opposition to the administration’s financial program was mounting, and much of it was coming from the South. Union was still on the president’s mind, and he needed to soothe the feelings of southerners worried both about northern speculation in real estate and new businesses and about the growing opposition to slavery in the North. Washington knew that slavery was wrong, but like other slaveholding planters he scarcely knew how to live without his slaves. He just hoped that sooner or later the institution of slavery would naturally disappear.

Since he had learned from his travels that the country was prospering and that “tranquility reigns among the people,” he had as yet little appreciation of how bad things would get and how the dark cloud of the controversy over slavery, hardly visible at first, would grow to threaten the Union. He had done more than any other American to reconcile his fellow citizens to the new Constitution and to the new national government. But he had done little or nothing to deal with the one issue that eventually shattered the Union he had devoted his life to creating and preserving.