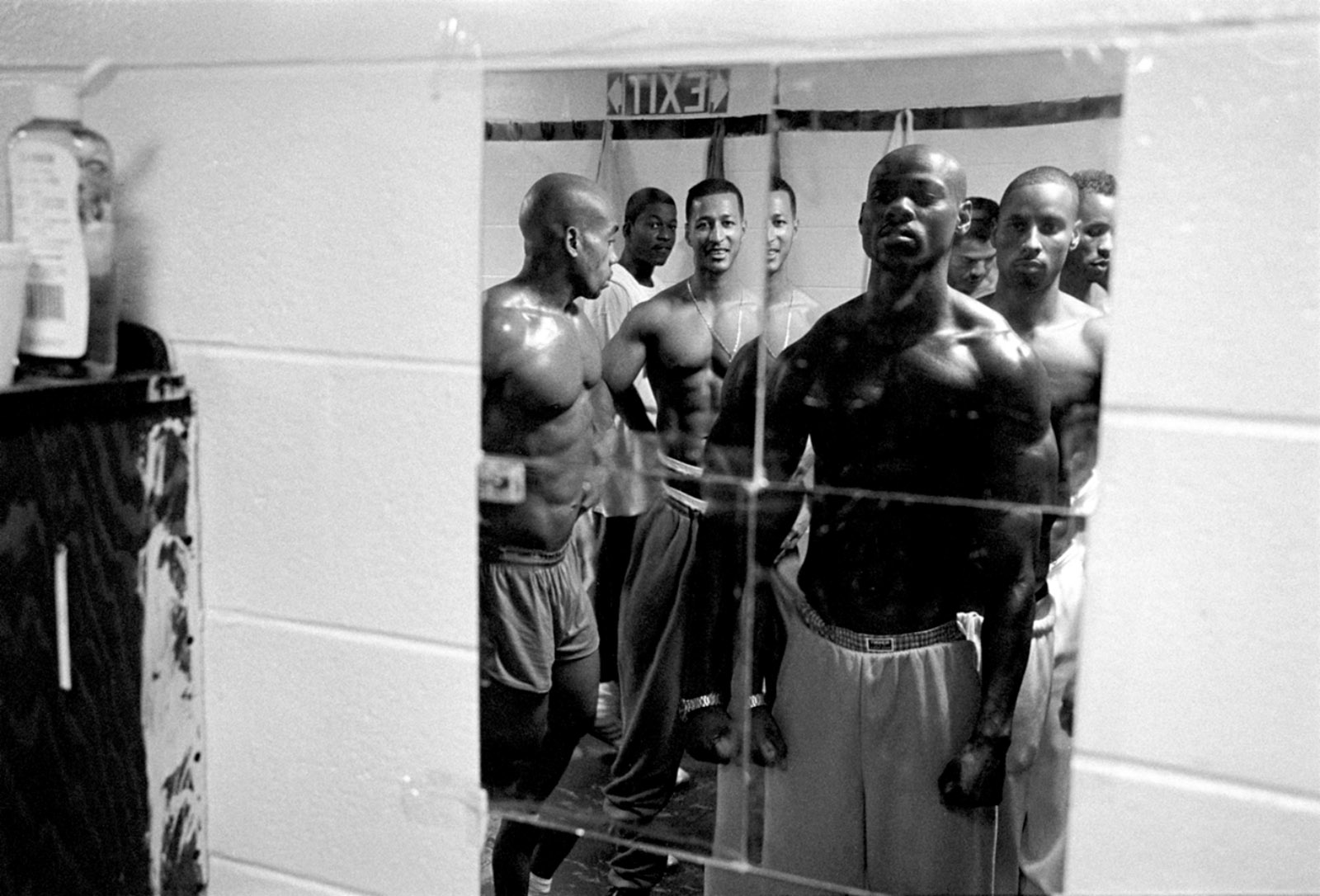

Isadora Kosofsky

A mother talking with her son through a window at the Florida Women’s Reception Center, a prison in Ocala, Florida, April 2016; photograph by Isadora Kosofsky from her series ‘Still My Mother, Still My Father,’ which documents parent–child visits in Florida prisons. An exhibition of her work will be on view at the Davis Orton Gallery, Hudson, New York, June 24–July 23, 2017.

Few claims about contemporary American society are more widely accepted on the left than that the dramatic growth of our prisons and jails has been driven by the war on drugs. In July 2015, President Barack Obama maintained that “the real reason our prison population is so high” is that we have “locked up more and more nonviolent drug offenders than ever before, for longer than ever before.” In her widely read 2010 book, The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander similarly argued that the war on drugs, pursued for the purpose of subordinating African-Americans newly freed from segregation, is primarily responsible for mass incarceration. These views have become conventional wisdom in liberal circles. But what if they are wrong?

There is little dispute that the United States faces a crisis of mass incarceration. Every year from 1972 to 2008, the number of Americans behind bars grew—at rates that far outstripped that of the population generally. As a result, the per capita rate of imprisonment increased nearly sixfold, from 93 per 100,000 to 536 per 100,000. Today, the rate has fallen slightly to 458 per 100,000, but there are still about 2.3 million people in our jails and prisons. (The overwhelming majority of this population—about two million people—are in local and state facilities, with federal prisons accounting for another 197,000 people, and other facilities such as immigrant detention and juvenile detention centers accounting for the rest.) Overall, we lock up more citizens than any other country in the world.

It is also indisputable that blacks and Hispanics are vastly overrepresented among those behind bars. They make up 31 percent of the general population, but almost twice that proportion—59 percent—of the state prison population. As the Sentencing Project, a Washington, D.C.–based criminal justice reform advocacy organization, notes in a 2013 report:

African-American males are six times more likely to be incarcerated than white males and 2.5 times more likely than Hispanic males. If current trends continue, one of every three black American males born today can expect to go to prison in his lifetime, as can one of every six Latino males—compared to one of every seventeen white males.1

Critics of these racial disparities, myself included, have often focused on drug crimes; while some of the racial disparities in the prison population reflect higher rates of offending among blacks and Hispanics, particularly with respect to violent and property crimes, the same is not true for drug offenses.2

According to anonymous surveys conducted by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, blacks, Hispanics, and whites use drugs at roughly equal rates. While there is less data available on drug trafficking, most users report that they obtain their drugs from people of the same race—suggesting similar rates of drug trafficking by whites, blacks, and Hispanics. Yet the incarceration rates for drug offenses are 34 per 100,000 for whites, 74 per 100,000 for Hispanics, and 193 per 100,000 for blacks. These striking disparities grew in tandem with the expansion of the inmate population generally. According to the Sentencing Project, “between 1980 and 2000, the US black drug arrest rate rose from 6.5 to 29.1 per 1,000 persons; during the same period, the white drug arrest rate increased from 3.5 to 4.6 per 1,000 persons.”

Drawing an analogy to Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander and others have argued that tough drug-sentencing laws have been a means to sustain the social control of the black population previously maintained by segregation. Ava DuVernay’s documentary 13th, released last fall, took the analogy still further, linking the disproportionate numbers of blacks behind bars to slavery.

But in Locked In, John Pfaff, a professor at Fordham Law School, makes a powerful case that the war on drugs has had very little effect on incarceration rates overall, or racial disparities in prison more specifically. In state prisons, which account for a large majority of the nation’s inmate population, only 16 percent of prisoners have been convicted of a drug crime. Moreover, the vast majority of those in prison for drug-related offenses—by one measure almost 95 percent of this group in state prisons and 98 percent of this group in federal prisons—have also been convicted on more serious charges, including violent crimes. All told, low-level, nonviolent drug offenders, the focus of much reform rhetoric and effort, make up only about 1 percent of all inmates in state prisons. If we released every prisoner who has been sentenced solely for a drug crime, we would still be the world leader in incarceration. Most strikingly, the racial disparities of our inmate population would barely budge: in state prisons, the percentage of white inmates would go up one point, the percentage of black inmates would go down one point, and the Hispanic percentage would remain the same.

Advertisement

Drug laws have had a more significant effect on the growth of the federal prison population. This is partly because most violent crimes (such as assault, murder, and armed robbery) are state crimes only, so state prisons have a higher relative percentage of violent criminals. In addition, federal and state drug laws often overlap, and state prosecutors have been happy to let federal prosecutors do the work, especially as federal law often carries more severe penalties for the same conduct. About half of federal prisoners have been convicted of a drug offense, and people serving time on such charges account for 42 percent of the growth in the federal prison population. But because federal prisoners make up only 13 percent of the total national prison population and 9 percent of the combined prison and jail population, the state numbers are much more significant.

Longer prison sentences are not the cause of mass incarceration either, according to Pfaff’s research. This is surprising, because from the mid-1970s to the early 2000s, state and federal legislatures repeatedly increased the penalties for a wide variety of crimes. Maximum sentences are often extreme. In the District of Columbia, for example, a first-time conviction for selling a small amount of cocaine can lead to a thirty-year sentence; a second conviction can result in up to sixty years behind bars—in theory. But in practice, Pfaff argues, few defendants serve such lengthy sentences. Most serve between one and three years in prison. And that range has not changed significantly over the period in which incarceration rates quintupled.

Instead, Pfaff maintains, overincarceration can be largely explained by the decisions of prosecutors. In recent decades, prosecutors have charged a larger proportion of those arrested with felonies rather than dropping charges or seeking only misdemeanor convictions, which at most lead to short jail sentences. When a police officer makes an arrest, it is the prosecutor who decides how to proceed. She can drop the charges, seek diversion (in which charges are dropped in exchange for treatment or some other sanction), or charge the suspect with crimes of varying degrees of severity. Thus, someone caught with drugs and a weapon could be charged with drug possession, drug trafficking, possession of a gun, or any combination of the three. These decisions can determine how much prison time the suspect is likely to receive.

The broad leeway accorded to prosecutors in whether and how to charge a suspect is a necessary part of the criminal justice system. We would not want everyone who is arrested to face the maximum possible sentence; in many instances, justice and mercy call for a more considered response, and prosecutorial discretion makes that possible. Nor could we afford to prosecute all those who are arrested. Moreover, this discretion is essential to plea bargaining, without which the criminal courts would grind to a halt.3

But, as Pfaff notes, prosecutors have more power than they used to. During the last four decades, legislatures have enacted more and more overlapping criminal laws, affording prosecutors a wider range of possible charges. Over time, prosecutors have on average become more aggressive in their charging decisions. But as prosecutors operate in three thousand distinct counties, this is not a coordinated, top-down phenomenon.

Prosecutors are “the most powerful actors in the criminal justice system,” Pfaff writes, yet they are largely unregulated. Police, by contrast, operate mostly in public, and they are constrained by the Fourth and Fifth Amendments and regular judicial oversight. Judges must explain their decisions in writing, which are then subject to appellate review. Legislators are accountable to the people for their actions, which are duly recorded and easily tracked. But prosecutors act behind a veil of secrecy. We know almost nothing about how they decide whether to charge a defendant. There is no requirement that they offer any explanation for their decisions. And courts have granted prosecutors immunity from damages suits even when they act unconstitutionally.

Prosecutors’ decisions about which kinds of charges to bring have had dramatic consequences. Consider, for example, the period from 1994 to 2008, when per capita incarceration rose every year. Over that period, reports of violent and property crimes fell steadily. So, too, did the number of arrests. The probability that a felony case, once charged, would lead to incarceration did not change. And the average time actually served stayed pretty much the same. What changed was the number of cases that prosecutors charged as felonies in state court: the likelihood that an arrest would lead to a felony charge doubled over that time. In other words, it was not crime rates, arrests, or sentence lengths, but admissions to prison, driven by decentralized prosecutorial decisions, that accounted for most of the growth in incarceration.

Advertisement

In Locking Up Our Own, James Forman Jr., a professor at Yale Law School and the son of a prominent civil rights leader, tells an even more surprising story. Forman agrees that the war on drugs has had only a minor part in the dramatic rise of incarceration rates. But his moving, nuanced, and candid account challenges another aspect of the “new Jim Crow” thesis. He shows that some of the most ardent proponents of tough-on-crime policies in the era that brought us mass incarceration were black politicians and community leaders—many of whom were veterans of the civil rights movement. They supported these policies not to subordinate African-Americans, but to protect them from the all-too-real scourges of crime and violence in many inner-city communities.

Forman’s book is centered on the experience of Washington, D.C., a majority-black city whose citizens and representatives repeatedly supported longer criminal sentences and aggressive policing. His story begins in 1975, when David Clarke, a white civil rights activist who became a D.C. city council member, introduced a bill to decriminalize marijuana. Clarke argued that the police and prosecutors disproportionately targeted black citizens for marijuana arrests and prosecutions. But the black community and its leaders rejected Clarke’s entreaty. The head of the opposition was Douglas Moore, a black civil rights activist associated with Stokely Carmichael’s Black United Front. The bill was also opposed by the city’s black clergy, as well as John Fauntleroy, one of the city’s first black judges. The city council voted it down.

The reason much of the black community opposed decriminalization? Heroin. At that time, heroin had ravaged the District of Columbia. By 1969, an astonishing 45 percent of those admitted to D.C. jails were heroin addicts. By 1971, Forman writes, “there were about fifteen times more heroin addicts in Washington, D.C., than in all of England.” They were overwhelmingly black, and they committed hundreds of crimes a year to maintain their habits. The community rejected decriminalization of marijuana because they worried that marijuana, and any toleration of it, might be a gateway to heroin.

Nor was D.C. unique. In Los Angeles in the 1970s and early 1980s, Maxine Waters pressed for harsh criminal sentences for PCP sellers. The NAACP Citizens’ Mobilization Against Crime and the Amsterdam News, one of the oldest black newspapers in the country, pressed for harsh mandatory minimums for drug traffickers. Detroit mayor Coleman Young advocated mandatory minimums for people who committed crimes while armed. And Damon Keith, a black civil rights leader and judge in Detroit, urged tougher law enforcement against drug pushers.

This was before the crack epidemic took hold, causing even greater levels of violence in inner-city communities. Among those who embraced a war on drugs in response to crack cocaine were D.C. mayor Marion Barry, another civil rights veteran, who called drug dealers “the scourge of the earth” long before he himself was arrested for smoking crack cocaine in an FBI sting operation in 1990; Jesse Jackson, who bragged that he would out-tough George H.W. Bush and Michael Dukakis in fighting the “war on drugs”; and Harlem’s congressional representative, Charles Rangel.

Still another surprising advocate of tough justice was Eric Holder. In the 1990s, years before he became President Obama’s attorney general and a leading critic of the severity of the criminal justice system, Holder was the first black US attorney for the District of Columbia. There, he launched Operation Ceasefire, a policing campaign that used traffic stops as a pretext to search for illegal firearms—a forerunner of New York City’s aggressive stop-and-frisk policing.

For all of these black leaders, Forman argues, “safety was a civil rights issue.” They were responding to the violent crime that beset their communities, and as often as not they supported harsh criminal justice measures to fight it.

These facts do not negate the standard account of mass incarceration, but they certainly complicate it. The problem cannot be reduced to drug laws, longer sentences, a crackdown on nonviolent offenders, or a racist conspiracy. Responses to violent crime—including by black leaders concerned about the degradation of their communities—and the radically decentralized decisions of tens of thousands of prosecutors drove much of the growth.

Both Forman and Pfaff agree that racial bias remains an essential part of the story of our criminal justice system, even if its influence is more indirect and nuanced than is sometimes asserted. While some black leaders clearly supported harsh criminal responses, their support was generally not sufficient to see such measures enacted without substantial white support. And some more powerful forces undeniably pursued racist strategies: the Nixon administration, for example, saw a war on crime as a way to drive a wedge between the Democratic Party and southern whites, and George H.W. Bush’s Willie Horton ad was similarly motivated.

In addition, as Forman puts it, “racism shaped the political, economic, and legal context in which the black community and its elected representatives made their choices.” Many African-Americans would have preferred what Detroit congressman John Conyers called for—a Marshall Plan for the inner city. But Americans were more willing to respond to inner-city crime with police and prisons than with better schools, subsidized drug rehab programs, and economic development.

More broadly, racism affects how the nation responds to the prison crisis. The predominance of blacks and Hispanics in the inmate population has made the issue of mass incarceration far less visible to the political establishment and the average voter, leading to a toleration of the status quo that would be inconceivable if white men were disproportionately behind bars. The politics of crime would be very different if one of every three white male babies born today could expect to spend time in prison during his life. This racial dimension has played a central part in America’s failure to confront the situation of our jails and prisons today.

The correctives offered by Forman and Pfaff have consequences not only for how we understand mass incarceration, but for how we go about fixing it. It is not enough to amend criminal statutes, eliminate mandatory minimums, decriminalize drugs, and improve reentry programs. The most effective way to reduce the rate of incarceration is to reduce admissions to prison in the first place. And in order to do that, according to Pfaff, we must change the practices that have led prosecutors to file felony charges against so many.

Two states have attempted promising prosecutorial reforms. New Jersey has imposed guidelines on prosecutors that aim to restrict their discretion in deciding when to press felony charges. But as the adoption of federal sentencing guidelines for judges has shown, guidelines tend to increase severity across the board. We are generally more understanding of wrongdoing the more we know about a particular perpetrator’s circumstances, whereas guidelines are adopted in the abstract, without a specific individual in mind, and run the risk of overpunishing. That risk can be mitigated by reassessing and adjusting the guidelines if they lead to increased punishment. But absent such a commitment, guidelines themselves do not necessarily alleviate severity.

California has taken another approach, aimed at making jurisdictions bear financial responsibility for prosecutorial decisions. Prosecutors are county officials, but when they send someone to prison, the cost of imprisonment is borne by the state. In 2011, California required a larger number of convicted criminals to serve time in county jails, which forces the counties themselves to bear the cost of incarceration. It led to a significant reduction in the state’s prison population, accompanied by a smaller increase in the county jail population, for an overall drop in incarceration. But when counties were unable to afford the extra jail costs, the state legislature subsidized them, thereby undermining the incentive for prosecutors to send fewer people to prison. Still, such reforms, if more widely adopted, could change the charging practices of prosecutors.

Pfaff also recommends that state governments increase funding for public defenders, a reform that is warranted quite apart from the implications it has for incarceration rates. States have never adequately funded indigent criminal defense, even though it is a constitutional obligation. Better defense counsel would reduce prison admissions by helping to forestall coerced or ill-informed guilty pleas and more fully protecting defendants’ rights. But the long-standing failure of state governments to provide sufficient funding for indigent defense offers little reason for hope. Americans seem to like the “efficiency” created by a one-sided system in which prosecutors’ resources vastly outstrip those of defense attorneys.

A potentially more promising suggestion is either to insulate prosecutors from political control, on the theory that the politics of crime tends to favor severe punishment, or alternatively to change the politics of district attorney elections by supporting reform candidates in those contests. The vast majority of district attorneys run unopposed, and voter participation in such elections is notoriously low. A concerted effort to support reform candidates could encourage prosecutors to favor “smart” over “tough” approaches to charging decisions. The ACLU, where I am national legal director, recently conducted an intensive public education campaign in Philadelphia in connection with its district attorney primary, emphasizing prosecutors’ responsibility for mass incarceration. The most liberal candidate, a former public defender, won the race.

While Pfaff is right to concentrate on prosecutors, he may have underestimated the extent to which prosecutorial decisions are shaped by tough-on-crime legislation, and therefore the extent to which reducing statutory maximum penalties would help. Harsh criminal statutes deliver to prosecutors the message that if they want to succeed politically, it’s best to come down hard on crime. At the same time, the statutes afford prosecutors a very powerful tool. The larger the statutory maximum penalty a defendant faces if he goes to trial, the more pressure he will feel to cut a deal and plead guilty. Statutes carrying draconian punishments, even if not often imposed, greatly enhance a prosecutor’s bargaining power. Some 95 percent of criminal convictions result from guilty pleas. Thus, by reducing maximum sentences, legislative reform could encourage different behavior from prosecutors.

The fact that the criminal justice system is so decentralized—among fifty states and over three thousand distinct counties—suggests, however, that the most important reforms are likely to be cultural. No one authority has the power to impose nationwide reform. But here there is good news: a cultural shift is already underway. Per capita incarceration peaked in 2008 and has dropped ever since. The decline is much less steep than the rise, and we still have a very long way to go to make up for thirty-six years of unremitting growth. But the trend is in the right direction. Overall, the nation’s imprisonment rate dropped by 8 percent between 2010 and 2015.

This shift is reflected in legislation as well: from 2000 to 2007, state legislatures passed three laws increasing the severity of the penal code for every one law that decreased severity, but from 2007 to 2012, the ratio was reversed. Criminal justice reform attracts broad bipartisan support these days, from blacks and whites, liberals and conservatives. Reform is championed by such diverse voices as Senators Cory Booker and Mike Lee, the Koch brothers and George Soros, Americans for Tax Reform, the Center for American Progress, the ACLU, the Faith & Freedom Coalition, FreedomWorks, and Right on Crime.

President Donald Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions have sought to resurrect the knee-jerk “tough on crime” politics that brought us mass incarceration, but it’s not clear that there is much appetite for their approach. On November 8, 2016, the state of Oklahoma voted for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton by 65–29 percent, yet simultaneously approved ballot measures to reduce many drug and property crimes from felonies to misdemeanors, and to reinvest the savings in rehabilitation programs for convicted criminals.

But here’s the difficulty. If we are to make real progress on reducing incarceration rates, reforms must extend to those who commit violent crimes. The majority of state prisoners are there for violent crimes, not low-level nonviolent offenses. Any reforms that do not confront that fact will be insufficient. One way to start would be to focus on older prisoners and those who have already served long sentences. Because most individuals “age out” of criminal behavior, keeping older people locked up for lengthy periods brings distinctly diminishing returns as a form of crime prevention. Deterrence is more a function of the certainty that one will be punished than the severity of the punishment, so reductions in the lengths of sentences ought not lead to increased crime. And as Forman suggests in an inspiring account of an armed robbery case he handled as a public defender, part of the solution may involve encouraging victims to favor mercy rather than vengeance.

At the same time, every reformer lives in dread of another Willie Horton incident, in which a prisoner given his freedom as a matter of discretion and mercy commits another brutal crime. Most reforms thus far have steered clear of dealing with those convicted of violent crimes. President Obama’s much-acclaimed clemency initiative, for example, which pardoned or reduced the sentences of two thousand federal drug offenders, disqualified anyone with a history of violence. Until we tackle the much more vexing problem of violent crime, we will do little to address the causes of our incarceration crisis. It’s a daunting challenge, but one that justice and conscience demand that we confront.

-

1

See “Report of the Sentencing Project to the United Nations Human Rights Committee Regarding Racial Disparities in the United States Criminal Justice System,” August 2013, available at entencingproject.org. ↩

-

2

Most crime is intraracial, and black and Hispanic victimization rates are substantially higher than white victimization rates, suggesting higher rates of offending with respect to at least certain violent crimes. See Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Prisoners in 2015” (December 2016), Table 9. For example, African-Americans are 6.5 times more likely to be homicide victims than whites. This is largely because crime is concentrated in poor urban neighborhoods, which tend to be highly segregated. See Violence Policy Center, “Black Homicide Victimization in the United States” (2017). ↩

-

3

On the pernicious effects of plea bargaining on the justice system, see Jed S. Rakoff, “Why Innocent People Plead Guilty,” The New York Review, November 20, 2014. ↩