Louie, the FX show that the comedian Louis C.K. wrote, directed, and starred in for five seasons, is credited with expanding the possibilities of the half-hour television comedy. Its first-person, expressionistic sensibility was something new for the sitcom when the show debuted in 2010. Another way to appreciate its cultural significance and its genius is to consider this: Louie may be the first sitcom featuring children that’s wholly inappropriate for children to watch. The show’s title character, based on C.K. himself, is a divorced stand-up comedian with shared custody of his two school-aged daughters, six and nine years old in the first season.

Louie is a rumpled, out-of-shape, unfashionably goateed white man who has not aged into comfortable success. On days when he has his kids, he picks them up from school, cooks their dinner, reminds them to do their homework, tucks them in at night, and brings them to school again the next morning. At forty-one, Louie is baffled by the shape his life is taking, especially by the fact that his divorce has conferred on him full parental authority every other week. The show is set to jazz, and the sweeping, wheeling camera and music are the chief instruments of comedy, along with C.K.’s reaction shots—wincing, dubious, resigned.

Louie takes fatherhood seriously. His own father, he tells a friend in one episode, was “not around,” and he wants to do it differently. But the show is always threatening to pull the rug out from under Louie’s great-dad conceit—not because he isn’t a good father, but because the value of his work is unknown and unknowable. The same social forces that have brought more men into the web of child care have also revealed that children do fine with all kinds of caretakers: grandparents, nannies, day care workers—pretty much any reliable, kind adult could perform any one of Louie’s tasks with no detriment to his daughters.

He cares for them in a state of contingency. Does it really matter that he cooks their meals from scratch? Do all these clocked hours make a difference in the end? And is he hiding behind the kids to avoid dealing with other parts of his life? “You’ve been a good father,” his ex-wife acknowledges, urging him to audition for a late-night show hosting spot he’s been shortlisted for. “But no one needs a father very much.” It’s a great bit of deadpan three seasons into a show that has made so much of Louie’s fatherhood. “Yes, you would be spending less time with the girls,” she goes on, exasperated, “but it’s because you’d have a job, Louie.”

No one can say for sure how much the girls need him, but there’s no question that he needs them. When he doesn’t have the kids, his days are a wasteland: poker with a raunchy group of comedian friends, ice cream benders, masturbation to the local newscasters on TV. He dates a variety of emotionally and psychologically damaged women as well as some well-adjusted ones with whom it never works out. At night, he does gigs at the Comedy Cellar and Caroline’s, and the stand-up bits are interspersed through each episode.

C.K.’s stand-up is genial yet dirty. He has pondered child molesters (“From their point of view, it must be amazing, for them to risk so much”) and bestiality (“If no one ever said, ‘you should not have sex with animals,’ I would totally have sex with animals, all the time”), as well as more run-of-the-mill aspects of the post-divorce dating scene (“I like Jewish girls, they give tough hand jobs”). He finds no end of occasions to mime sex acts, especially masturbation, onstage.

When he started releasing hour-long comedy specials ten years ago, C.K.’s material was long on kids, marriage, men and women, and getting older and fatter. These subjects are still a big part of his acts, especially in Louie, but he’s gotten even more traction with observations about our national mood disorder: the irritable, selfish public behavior and private melancholy of Americans in the smartphone age (or sometimes, more specifically, affluent white Americans). He’s most effective when he uses himself as representative American jerk and melancholic. In a Saturday Night Live appearance in April, he described a recent trip out of town during which he felt he wasn’t getting his fair share of white privilege because the hotel staff didn’t treat his lost laundry as a top-level emergency.

C.K. beams when he laughs at his own jokes and his amusement seems genuine and deep, taking the edge off his provocations as well as his depressive observations about his own life. In 2017, his latest stand-up special, released this spring, he has a riff on suicide always being an option. “But don’t get me wrong, I like life. I haven’t killed myself. That’s exactly how much I like life. With a razor-thin margin.” In Louie, his will to live is almost exclusively bound up with his daughters: “I was thinking that on Jane’s eighteenth birthday,” he tells a fellow parent, “that’s the day I stop being a dad, right?… The day I just become a guy, not daddy. I just become some dude. I think on that day”—he pauses—“I might kill myself.” He looks as surprised as his interlocutor at where his train of thought has taken him.

Advertisement

Sexual perversity is around every corner in Louie, whether it’s an old woman who opens her apartment door stark naked, flashes Louie, then hisses “Pig!,” or a jittery bookstore clerk (played by Chloë Sevigny) who insists on helping him track down an old flame and then gets so turned on by the project that she masturbates to orgasm in the middle of their conversation in a coffee shop.

You could play the masturbating woman strictly for laughs, or it could be something darker, unnerving. C.K. tips it toward comedy (there’s a brilliant exchange of glances between Louis and the only other person in the coffee shop, an austere male barista), but not too far so; the scene has a complexity of tone typical of the show as a whole. Until she actually puts her hand between her legs, we don’t know what Sevigny’s character, who has the air of an increasingly agitated, eccentric loner, is going to do. When it happens, the gesture of pulling aside the waistband of her skirt is as startling as an act of violence.

Over the show’s run, Louis has been the victim of two incidents of sexual assault: one by a dentist who seems to have put his penis in Louis’s mouth while he was sedated in the dental chair, and one by a woman who’s so angry that Louis won’t go down on her after she gave him a blow job that she smashes his head against a car window until he capitulates. Is it funny? Yes, but it’s also something other than funny. Sitcoms of the last twenty years like Curb Your Enthusiasm, Arrested Development, or 30 Rock have been innovative and dazzlingly funny, but they’re also uniformly light, issuing a steady, rhythmic pulse of levity at predictably short intervals, making for great bedtime viewing.

Louie is something different, a comedy about bodily shame and sexual despair and the narrowing possibilities of middle age whose turns are unpredictable, enigmatic, and carry emotional risks. The jokes push beyond the familiar conceit that Louis is a sad sack who can’t get a date. In fact he often does have a date, and sex, but that only opens him up to a world of unsettling discoveries about himself and his partners. Louie’s New York is a sexually permissive playground in which hardly anyone can get what he or she wants. More often than not, people’s sexual appetites alienate them from one another, or even cause harm.

Meanwhile, the children are in jangling proximity to all this perversion. The scenes involving child actors are of course clean, but they’re only a frame away from Louie’s off-hours depravity, raising anxious questions about modern fatherhood. Can a divorced father on the prowl also make himself safely and intimately available to his children? Can Louie rein in his depressive, pessimistic, and self-destructive impulses and give himself over to his daughters’ needs for hours and days at a time while still retaining enough of himself to write comedy? The answer, and the source of the show’s rogue joy, is yes—incredibly, yes.

There probably won’t be another season of Louie, C.K. has said. Instead, he recently released on his website the self-funded show Horace and Pete, also written and directed and starring C.K. Though the show has a distinguished celebrity cast (including Edie Falco, Alan Alda, Jessica Lange, and Steve Buscemi), C.K. made the show quietly in a matter of weeks and released it without advance publicity. Horace and Pete is not a comedy. It is, in fact, a tragedy, and there’s no missing the fact that this show is also about fatherhood, or, more precisely, patrimony. Three siblings in their late forties and early fifties have inherited a family business, a one-hundred-year-old bar in a formerly white, working-class neighborhood in Brooklyn that’s now gentrifying. The bar doesn’t make much money, but it’s now extremely valuable real estate. Should they sell it?

Advertisement

The look and feel of the show is a sharp contrast to Louie, so much so that it seems like an exercise in voluntary artistic deprivation for C.K.: multiple cameras, just three interior sets, almost no music. And in place of the associative logic of Louie, with its segments in ambiguous relationship to one another, we have the unspooling of a linear plot. The technical elements of Louie that made the show move and breathe are absent here. Instead, the focus is on writing and acting and bodies against an unchanging backdrop; characters reveal their stories in nothing more cinematically sophisticated than monologues.

It is, as critics have noted, much like a filmed play, and its themes of family dysfunction and vexed paternal lineage evoke not only twentieth-century American playwrights like Arthur Miller and Eugene O’Neill, but Henrik Ibsen before them. And while the show is set in the present—bar patrons yak about the Trump campaign—it also relies on some conspicuously archaic turns of plot. There are revelations of secret paternity. Not one but two characters have given an unwanted infant to a sibling to raise as his or her own.

The bar, Horace and Pete’s, has been passed down through many generations of the Wittel family, always to sons named Horace and Pete after the original proprietors. But now the lineage is threatening to break down. Depending on how you look at it, the reason for the breakdown is either bad fathering or the rise of Wittel women, or both. Sylvia (Falco), the oldest of the siblings, is trying to convince her brothers Horace and Pete (C.K. and Buscemi) to sell it. The bar had previously been owned only by male relatives, but because their father died without a will, Sylvia is now a common-law co-owner with her brothers. “This place is worth millions,” she tells Horace—they could divide the money and get on with their lives.

Getting out, moving on, and starting over are big with Sylvia; she has the least emotional attachment to the family business of all the siblings—in fact, she loathes it. When the siblings were young, their mother left their violent father and raised the kids by herself uptown. Sylvia cherishes her mother’s bravery and indulges no sentimentality about the generations of Horaces and Petes. “My father was a wife beater and a fucking brute and a narcissist. And thank god our mother got us out of here. How many wives have been beaten in this place?” she says to Uncle Pete (Alda). And to Horace: “Ma got out. She got us out. It kills me that you’re back here.”

But Horace, played by C.K., doesn’t want to sell. When their father died a year ago he left his job as an accountant to take over the bar. He is helped by his brother Pete, a heavily medicated psychotic who spent much of his life hospitalized for mental illness but now lives in a room behind the bar and helps out with housekeeping, and by belligerent, casually racist Uncle Pete, who works behind the bar and yells at the bar’s new hipster customers to get off their phones.

If the family sold the bar, Pete and Uncle Pete would probably never find work again. But that’s not the only reason Horace doesn’t want to sell. Horace has been living for the last year in his parents’ old apartment above the bar, still decorated in a dingy 1970s palate of brown, rusty orange, and avocado and olive greens, betraying nothing of himself. There is no self-expression in running the business: Horace has stepped into a role occupied by seven other Horaces before him, and that, one senses, is the appeal of it. His patrimony gives form and structure and, potentially, meaning to his life: “This is Horace and Pete’s, and I’m Horace,” he says to Sylvia.

It’s hard not to see a parallel in there somewhere to C.K. himself, who seems to be taking a break from being a vaunted comedy innovator by seeking refuge in patently older modes. The sets, the multicamera format, the dramatic staging, the long monologues, and the antiquated plot devices all refer to earlier points in the history of drama and television; this is not going to be something new, everything about the show seems to scream. Of course, it’s such an anomaly among today’s shows that it feels like something new.

Horace, in any case, likes the bar precisely for its lack of novelty or growth potential. “Does every business have to make a profit?” he asks practical Sylvia. “Can’t any place just be a place? People come here. They’ve come here for a hundred years.” To which Sylvia’s typical reply is, “A hundred years of misery is enough.” Tough, foul-mouthed, unsparing, mirthless, Falco’s leonine Sylvia has a moral authority and radiance in spite of her cruelty, at times, to various family members. A hundred years of misery seems no exaggeration—misery soaks these characters, a joyless lot.

Yet one has the feeling that the show wants to defend the family business, and maybe even hold out the possibility that some things about the older, whiter, prefeminist order it represents are worth defending. No character can quite find the words to do so, however. Uncle Pete and Horace merely keep pointing to the bar’s sheer endurance. A community fixture, an informal neighborhood institution, a working connection to the past—it’s no small thing; do we have to give it up for lost just because its owners were wife beaters? On the other hand, this particular institution is a bar that caters to the neighborhood’s hard drinkers, where at least one patron has died of alcohol poisoning and at least one other has committed double homicide. C.K. stacks the deck against Horace and Pete’s, and subtly evades a reckoning.

Sylvia finally prevails (though not in the way she intended) and has the last word, an ascendance that seems inevitable. But the show leaves us with an interesting twist on what has seemed, broadly speaking, to be a conflict between the Wittel men and the Wittel women.

The last episode contains a flashback to the siblings’ childhood, the decisive day that the mother and children sneak out of the house and leave their father for good. We see the elder Horace (also played by C.K.) hit his boys, pull his wife (played by Falco) by the hair, and generally frighten and intimidate everyone in the family—except for the teenaged Sylvia, who comes home after curfew defiant and ends up having the last word even with her enraged father. Until now, the show has discussed paternal legacy—financial and otherwise—as something passed down from father to son, but the scenes of young Sylvia with her two parents point to a loophole in the patriarchal order. It’s not from her mild-mannered mother that Sylvia inherited her toughness and ferocity—it’s from Dad.

This Issue

July 13, 2017

A Presumption of Guilt

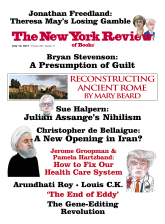

The Brave New World of Gene Editing