Not long ago, a relative called us for advice about a hospital bill. A public interest lawyer in New York, he had developed chest pain when exercising and consulted his internist, who ordered a stress test with an echocardiogram. To his relief, no abnormalities were found. Distress came later, when he saw that the hospital had charged some $8,000 for this test. Despite having excellent insurance, he was informed that he was responsible for $2,000 of the total.

The bill seemed exorbitant to us, and we suggested that he contact other medical centers in the city to find out what they would charge for the same examination. To his surprise, he discovered that prices ranged from about $1,200 to $6,000. When he called the billing office at the hospital where his test was performed and asked why the echocardiogram was priced at such a high level, he did not receive a clear answer. Frustrated, he informed the hospital that he declined to pay. This resulted in several veiled threats, but he countered that he would contact the attorney general of New York about what he believed was abusive pricing without justification. After much back-and-forth, his internist intervened on his behalf, and the hospital dropped the demand for the $2,000 difference.

This story points to the extraordinary predicament of our current health care system. Since the implementation of President Obama’s Affordable Care Act (ACA)—and the mandatory coverage it brought—most patients needing a procedure such as an echocardiogram can count on some form of insurance. But Obamacare put no controls on the pricing of drugs or clinical care, leaving the profit-driven health industry mostly intact.1 As a result, patients are too often required to pay large out-of-pocket costs while insurance premiums have continued to rise. Most patients navigating the financial shoals of our health care system do not have relatives who are doctors to advise them, nor are they lawyers; and many do not have insurance policies as generous as our relative’s.

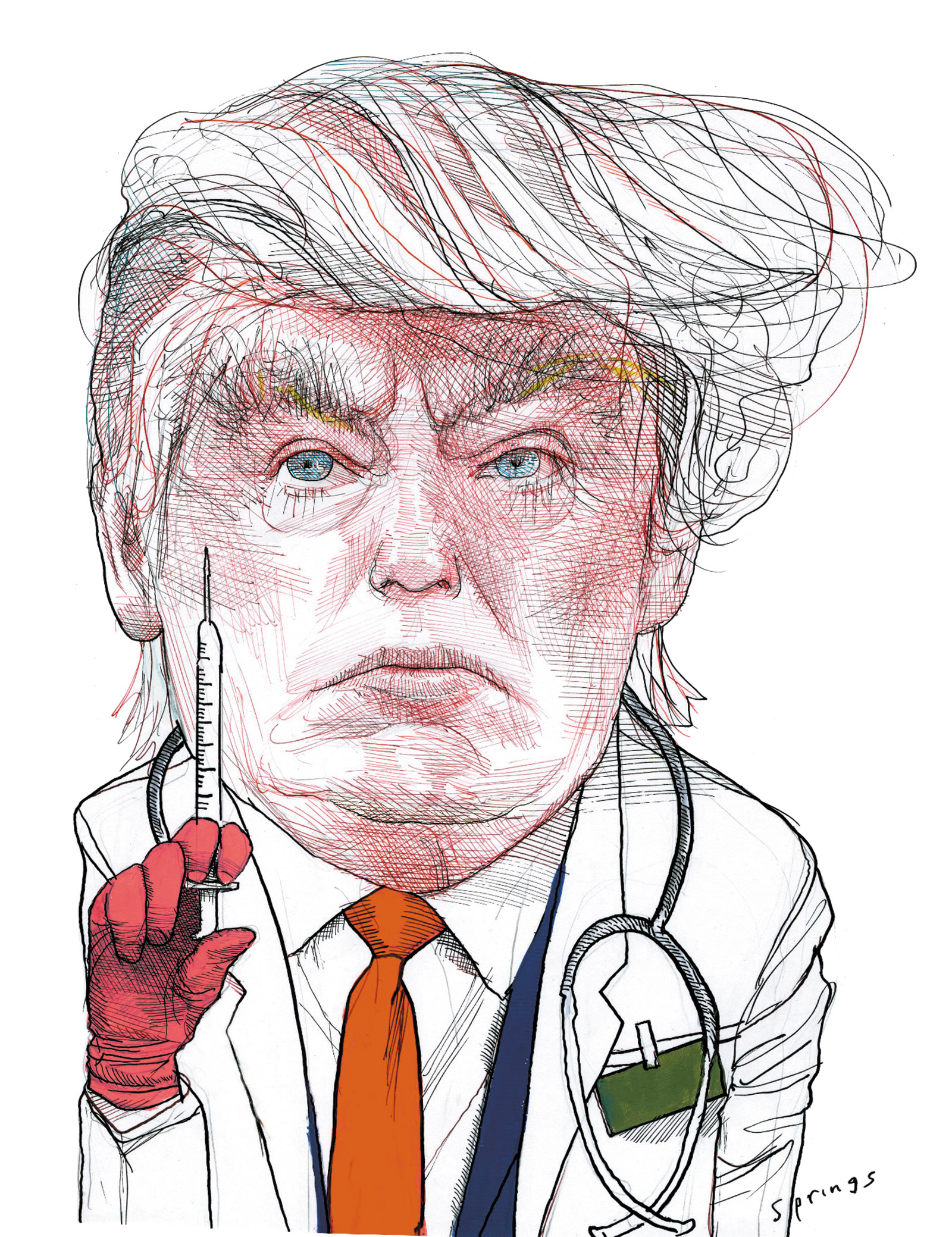

Now, if the Trump administration and a Republican-led Congress are successful in their efforts to replace the ACA with “a free market solution,” largely stripped of regulatory restraints, the situation could get much worse. In May, the House of Representatives passed its version of a bill (called the American Health Care Act or “Trumpcare”) aimed at dismantling Obamacare, and the Senate has been crafting its own bill. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that the House bill, if enacted, would leave 14 million people uninsured as soon as next year, and 23 million by 2026. Furthermore, this plan would make it even more costly for the neediest patients to access care.

At the center of both our flawed current system and its disastrous proposed replacement is a more fundamental reality: health care in the United States is enormously costly, often in ways that are baffling not only to patients but to doctors themselves. In An American Sickness, Elisabeth Rosenthal, a physician turned journalist, first at The New York Times and now at Kaiser Health News, sets out to explain how we got here. The book takes its structure from the way doctors record clinical notes, delineating a “chief complaint,” the “history of the present illness,” then a diagnosis, and finally a treatment. But here the sick patient is our health care system. With health care reform becoming one of the main issues of the current administration, An American Sickness could not be more timely or alarming.

Rosenthal identifies the “chief complaint” as an American medical system that “has stopped focusing on health or even science. Instead it attends more or less single-mindedly to its own profits.”

Who among us hasn’t opened a medical bill or an explanation of benefits statement and stared in disbelief at terrifying numbers? Who hasn’t puzzled over an insurance policy’s rules of copayments, deductibles, “in-network” and “out-of-network” payments—only to surrender in frustration and write a check, perhaps under threat of collection?

Rosenthal contends that the behavior of the health care market does not match that of other commodities. Instead, she points out, it defies economic logic:

More competitors vying for business doesn’t mean better prices; it can drive prices up, not down…. Economies of scale don’t translate to lower prices. With their market power, big providers can simply demand more…. Prices will rise to whatever the market will bear.

The American system was not always like this. Rosenthal gives a lucid and revealing history of American health care beginning with religious institutions ministering to the sick and dying in the nineteenth century. Absent effective treatments like antibiotics and anesthetics, therapy was not very costly, and recovery largely depended upon the body’s natural systems of resistance and repair. In the early 1900s, as clinical knowledge and treatment advanced, medications and surgeries were developed, and costs increased.

Advertisement

The question for hospitals at the time was how to cover expenses, not how to make money. The archetype for today’s insurance plans, developed at the Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas in the 1920s, was never intended to generate profit. It began when the hospital accumulated large numbers of unpaid bills for its services and decided to offer the local teachers’ union a deal: for six dollars a year, members “who subscribed were entitled to a twenty-one-day stay in the hospital, all costs included.” But there was a deductible: the insurance took effect only after a week of hospital costs pegged at $5 daily.

Baylor’s plan spread across the country and was given the name “Blue Cross.” The aim of this insurance was to protect patients from bankruptcy and to sustain hospitals and the charitable religious groups that supported them. Employer-based health insurance arose as a “quirk of history.” The federal government ruled in 1943 that no taxes would be levied on the money paid for employee health benefits. “When the National War Labor Board froze salaries during and after World War II,” Rosenthal writes, “companies facing severe labor shortages discovered that they could attract workers by offering health insurance.” After the war, in many other countries, a national health care system came to be regarded as a public good. But in the US, many viewed government-based health insurance as a form of socialism, and despite several attempts, proposals for such a system never could pass Congress.

As more Americans gained coverage, for-profit insurance companies sprang up to compete with the nonprofits Blue Cross and Blue Shield. The “Blues”—which coordinated their efforts starting in the 1940s and formally merged in 1982—accepted everyone, and all members paid the same rate no matter how old or how sick they were. (By the 1960s, more than fifty million Americans had hospital coverage from Blue Cross.) “Unencumbered by the Blues’ charitable mission,” Rosenthal writes, the private insurers “accepted only younger, healthier patients on whom they could make a profit.”

In the 1970s and 1980s, the rise of for-profit insurance companies like Aetna and Cigna made it difficult for the Blues to compete. In 1994, “hemorrhaging money,” Blue Cross and Blue Shield became for-profit as well. “This was the final nail in the coffin of old-fashioned noble-minded health insurance,” Rosenthal writes. The for-profit California Blues “gobbl[ed] up” their fellows in a dozen other states and, renamed WellPoint, emerged as the second-largest insurer in the country. Premiums rose rapidly. “WellPoint’s first priority appeared no longer to be its patient/members or even the companies and unions that used it as an insurer, but instead its shareholders and investors,” Rosenthal writes. This truth is often obscured; insurance companies market themselves in the media as caregivers, confusing the public, but they are not. The companies are fundamentally investment vehicles, maximizing profits to boost shareholder value.

Before the Blues turned into for-profit companies, they spent 95 percent of premiums on medical care. To increase profits, the Blues, along with other insurers, now spend as much as 20 percent of their premiums on marketing, lobbying, and administration. In contrast, Medicare, the federal program for seniors that enjoys widespread popularity, devotes nearly all of its funding to health care and only 1 to 2 percent to administration.2

Rosenthal’s indictment extends well beyond insurance companies. She looks carefully at hospitals, and the reader learns how they have been transformed by marketing consultants and administrators with business degrees to generate large profits, though many still enjoy a tax-exempt status as “nonprofit institutions”—meaning that they pay “almost no US property or payroll taxes.” Instead of profit, tax-exempt hospitals call it “operating surplus.” In 2011, the US government calculated that hospitals were getting an annual tax advantage of $24.6 billion. Steven Brill, who highlighted the predatory pricing that occurs in calculating costs of care in America’s Bitter Pill (2015), recently listed the yearly pay of the CEOs of large hospital systems, which often amounts to many millions of dollars. Rosenthal points out that “total cash compensation for hospital CEOs grew an average of 24 percent from 2011 to 2012 alone.”

Rosenthal’s case study is Providence Portland Medical Center in Portland, Oregon, founded by nuns in the 1850s. A century later, Providence, as other hospitals did, began charging patients for each service rendered. The hospitals hired administrators to “up-code” physician examinations and diagnoses in such a way as to maximize revenue. Providence then decided to stop paying salaries to physicians and treated them instead as independent contractors, turning each doctor into a “business.” A series of mergers and acquisitions followed, creating a giant hospital-based network that dominated geographic regions and had revenues in the billions. Rosenthal notes that Providence still presents itself as a “not-for-profit Catholic health care ministry,” invoking the tradition of its founding nuns. But it

Advertisement

comprises a weird mix of Mother Teresa and Goldman Sachs: one day it is donating $250,000 to help build a new teaching hospital in Haiti to replace one destroyed by the 2010 earthquake, and the next its new offshoot, Providence Ventures, is announcing the launch of a $150 million venture capital fund, led by a former Amazon executive.

As Rosenthal highlights, when doctors are turned primarily into businessmen, there can be egregious abuses of the system. Medicare tightly regulates reimbursement for cataract surgery, and in 2013 it reduced payments to ophthalmologists by 13 percent for simple procedures and 23 percent for complex operations as the technique became more efficient and required less time:

Many eye surgeons made up for Medicare’s increasingly stingy cataract payments by charging commercially insured patients more, leading to some staggering prices. Wendy Brezin, a Web designer in Jacksonville, Florida, had cataract surgery billed at $17,406. John Aravosis, a political blogger, was stunned to be billed over $10,000 for each eye.

Rosenthal also writes of a plastic surgeon who closed a cut on a girl’s face with three stitches and sent a bill to the family for $50,000. This kind of abuse is a betrayal of the profession and should not be tolerated.

But Rosenthal detracts from her story by repeatedly invoking unfounded stereotypes of physicians. She describes pathologists as “quiet, antisocial types.” The training of anesthesiologists is “not terribly difficult.” Rosenthal quotes a remark from an anonymous source regarding anesthesiologists overseeing the care of multiple patients and billing for this work “while sitting in the lounge monitoring their portfolios.” She asserts:

When I left medicine in the 1990s doctors commonly complained that they made less per hour than plumbers. Today, they seem more inclined to compare (negatively) their compensation to that of sports stars like LeBron James or titans of commerce like Lloyd Blankfein, the CEO of Goldman Sachs.

In an otherwise serious and well-researched work, these hyperbolic characterizations are gratuitous and disappointing.

Some of Rosenthal’s medical advice is inaccurate. She incorrectly claims that “neurosurgery to remove a brain tumor is never an emergency.” Tumors can press on the brain (sometimes due to bleeding) and cause a herniation, a life-threatening event in which the brain is squeezed on top of the spinal cord. This is an emergency that necessitates urgent neurosurgical intervention.

In the prescriptive section of the book, Rosenthal offers some useful pointers on contesting medical bills. As we suggested to our relative, she recommends contacting the hospital armed with comparable test charges and alerting a medical society or state agencies to possible abuse. (A surgical specialty society got the plastic surgeon to reduce his bill from $50,000 to $5,000 for the three stitches.)

However, she stumbles in the advice she gives on interacting with your physician. In a section called “In Your Doctor’s Office,” Rosenthal writes:

Here are some questions every doctor or healthcare provider should be able to answer for you at a doctor’s appointment:

1. How much will this test/surgery/exam cost? “I don’t know” or “It depends on your insurance” is not an answer. The doctor should give you a ballpark range with the cash price at the center where he or she refers.

When a patient seeks medical care, the doctor must listen and examine to formulate a diagnosis and recommend treatment options. In many clinics, appointments have been shaved down to some twenty minutes. Time is precious and should be spent on clinical care, rather than searching and quoting price lists. To be sure, information on cost is important, but accurate estimates can be difficult for both patients and doctors to obtain. The “cash price” often bears little relationship to what the patient’s actual cost will be because of the wide variation in deductibles and other specifics of each insurance plan. However, an administrator in the clinic, or a website, could appropriately provide assistance.

Importantly, there may also be unintended consequences of focusing the doctor–patient interaction on money. As Paul Krugman, the Nobel economist, has emphasized, patients should not be understood as “customers.” Doctoring, he avers, is not the same as selling cars. Indeed, we value our health differently than objects we purchase for utilitarian or luxury reasons.3 Research in cognitive psychology indicates that repeatedly cueing the physician to view patient care as a market exchange risks promoting selfish behavior and eroding essential aspects of our profession that contribute to high-quality health care, including pride in work, sense of duty, altruism, and collegiality.4

A recent national survey from the Mayo Clinic of some 6,800 physicians revealed that more than half, many of whom are salaried, reported feeling “burned out.”5 Commenting on this finding, a leading cognitive psychologist, Dan Ariely, and his coauthor, Dr. William Lanier, point out that this feeling is largely attributed to the transformation of the health system into “a sort of ‘fixing-people production line.’” This industrial approach has caused loss of physicians’ autonomy as well as micromanagement of their use of time and how they make decisions. The result is a change in the nature of the relationship of doctors and their patients, veering toward a “market” transaction rather than a communal relationship. The time to discuss not only the patient’s physical malady but its effects on other important aspects of his life—time that allows doctors and patients to forge personal bonds—has been all but eliminated.

In his book Getting Risk Right, Geoffrey Kabat offers insight into why the health care debate is so fraught and why it is so difficult to reach consensus:

Different groups—scientists (who themselves fall into different disciplines with different points of view), regulators, health officials, lay advocates, journalists, businessmen, lawyers—are shaped by different backgrounds and motivated by different beliefs and agendas. Depending on the issue at hand, the interests of these parties may conflict or may align and reinforce one another.

In the case of the Affordable Care Act, each group forcefully lobbied Congress and the Obama White House to protect its own share of the pie. In order to craft a bill that would pass Congress in the face of such potent lobbying, the Obama administration caved in to the pharmaceutical industry, omitting provisions that would constrain drug prices. Similarly, the insurance industry was given considerable leeway in setting premiums and deductibles in exchange for agreeing to offer policies that required essential benefits like maternity and preventative care, and that did not discriminate against patients with preexisting medical conditions. And to satisfy lawyers the administration did not pursue any serious tort reform in malpractice cases.

A painful compromise narrowly passed by a Democratic Congress, Obamacare achieved several laudable goals: providing coverage for tens of millions of previously uninsured Americans; ensuring care of preexisting conditions; allowing young adults to stay on their families’ policies until age twenty-six; subsidizing premiums for those of moderate incomes; and expanding Medicaid coverage for the poor, disabled, and elderly in many states. But it failed in one crucial respect, as Rosenthal observes: “The ACA did little…to control runaway spending.”

In the final section of her book, Rosenthal sets out a series of possible reforms to reduce the cost and chaos we now encounter. She rightly argues for greater transparency in the pricing of tests, like the echocardiogram our relative received. Patients should have easy access to websites that show comparative charges among different hospitals.

Rosenthal also proposes creating a national body of experts to assess the “cost effectiveness” and “value” of tests and treatments, like that in the United Kingdom, which sets access to these elements of care. We find this idea misguided. Paul Dolan and Daniel Kahneman have observed that the methodology used to calculate cost effectiveness is deeply flawed. And as Ashish Jha, a widely respected health policy researcher, recently noted, empirical data largely fail to support the notion that paying for “value” improves outcomes for patients.6

Further, much of the practice of medicine exists in a gray zone where there is no one right answer for everyone. Instead, there is continued disagreement among different groups of experts about what is best. Kabat explains in Getting Risk Right that experts have their own biases, often ideological rather than financial. He debunks

the simplistic notion that the “consensus among scientists” is always correct. This is a widely invoked criterion or shortcut for determining who is “right” in a scientific controversy. However, the results of a scientific study should not be expected to line up on one side or the other of a neat yes/no dichotomy. Unfortunately, the science is not always clear-cut, and the consensus on a particular question at any given moment may not be correct.

The American Health Care Act (Trumpcare) has been framed as “freedom of choice,” with minimally regulated competition in the health care market. As a result, patients of limited financial means will be at the mercy of unshackled insurance companies. Some people with preexisting medical conditions may be unable to get affordable insurance, while an estimated 14 million low-income Americans who now depend on Medicaid for health insurance will no longer qualify. Perhaps unsurprisingly, recent polls have consistently shown that, however dissatisfied they are with the current system, a wide majority of Americans are against repeal of Obamacare.

Republican senators have been working behind closed doors on their version of Trumpcare and may try to rush it to a vote as soon as the CBO can analyze its effects on health care costs and coverage. In early June, Senator Claire McCaskill, Democrat of Missouri, decried the lack of open debate about “a bill that impacts one-sixth of the economy.” Even if it doesn’t pass the Senate, the Trump health reform has led to new uncertainty in the health insurance market, with some insurers withdrawing from the exchanges set up under Obamacare.

What is a feasible step to begin to remedy our costly and chaotic health care system? Many industrialized nations, including Germany, Japan, Belgium, and others, have uniform negotiated national fee schedules for hospital admissions and clinical encounters with doctors. Medicare also does this. Furthermore, Medicare markedly decreases administrative costs for both doctors and hospitals, compared to private insurance.

A public option like Medicare that provides vital services and devotes nearly all of its funds to patient care, actively competing in the marketplace with private insurance, would be a welcome step in the right direction.7 This could achieve a goal unmet by either Obamacare or the Trumpcare plan: to remove money as the centerpiece of our health care system and restore the essential communal relationship that sustains patients and physicians alike.

—June 15, 2017

-

1

“Bending the cost curve” was proposed to occur through increased “efficiency” and reduced “waste.” It was projected that some $80 billion would be saved by mandating the use of electronic medical records, but these savings did not materialize. See Pamela Hartzband and Jerome Groopman, “Obama’s $80 Billion Exaggeration,” The Wall Street Journal, March 12, 2009. ↩

-

2

See “Setting the Record Straight on Medicare’s Overhead Costs,” Physicians for a National Health Program, February 20, 2013. ↩

-

3

See Paul Krugman, “Patients Are Not Consumers,” The New York Times, April 22, 2011; and Pamela Hartzband and Jerome Groopman, “The New Language of Medicine,” The New England Journal of Medicine, October 13, 2011. ↩

-

4

See Pamela Hartzband and Jerome Groopman, “Money and the Changing Culture of Medicine,” The New England Journal of Medicine, January 8, 2009. ↩

-

5

See Tait D. Shanafelt et al., “Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction with Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2014,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, February 2015; Dan Ariely and William L. Lanier, “Disturbing Trends in Physician Burnout and Satisfaction with Work-Life Balance: Dealing with Malady Among the Nation’s Healers,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, December 2015; see also Pamela Hartzband and Jerome Groopman, “Medical Taylorism,” The New England Journal of Medicine, January 14, 2016. ↩

-

6

This truth is largely ignored in both Democratic and Republican reform plans, which seek to implement rigid top-down standards for care. See Pamela Hartzband and Jerome Groopman, “Rise of the Medical Expertocracy,” The Wall Street Journal, March 31, 2012; Pamela Hartzband and Jerome Groopman, “There Is More to Life Than Death,” The New England Journal of Medicine, September 13, 2012; Paul Dolan, “Developing Methods That Really Do Value the ‘Q’ in the QALY,” Health Economics, Policy and Law, January 1, 2008; Paul Dolan and Daniel Kahneman, “Interpretations of Utility and Their Implications for the Valuation of Health,” The Economic Journal, December 20, 2008; Ashish K. Jha, “Value-Based Purchasing: Time for Reboot or Time to Move On?,” The Journal of the American Medical Association, March 21, 2017. ↩

-

7

Care should be understood not only as an individual right, but as a social responsibility. Other Western nations have such a blend of private and public options. See Anu Partanen, “The Fake Freedom of American Health Care,” The New York Times, March 18, 2017. ↩